The results of the survey suggest that there are many traits that are linked with levels of religious knowledge. These include demographic factors, such as age and education, as well as religious affiliation.

But which of these traits are strongly connected with greater knowledge, and which are related only tangentially, if at all? This chapter attempts to answer this question, based on a technique known as multiple regression analysis.

The multiple regression analysis begins with a statistical model that includes seven main variables: religious affiliation, education level, race and ethnicity, gender, age, region, and marital status. It considers the impact of each of those variables independent of the others. Then the analysis adds into the model, one at a time, several other possible factors associated with religious knowledge, such as religious service attendance, whether the respondent has ever taken a class about world religions, or whether they personally know members of several different religious groups. For example, this analysis shows whether religious service attendance is related to religious knowledge, independent of religious affiliation and other demographic characteristics. This produces a picture of how much each factor contributes to people’s performance on the religious knowledge survey, independent of the other variables. Put somewhat differently, this method of analysis imagines a survey respondent who is completely typical in all ways but one and calculates the impact of that one factor on the respondent’s level of religious knowledge.

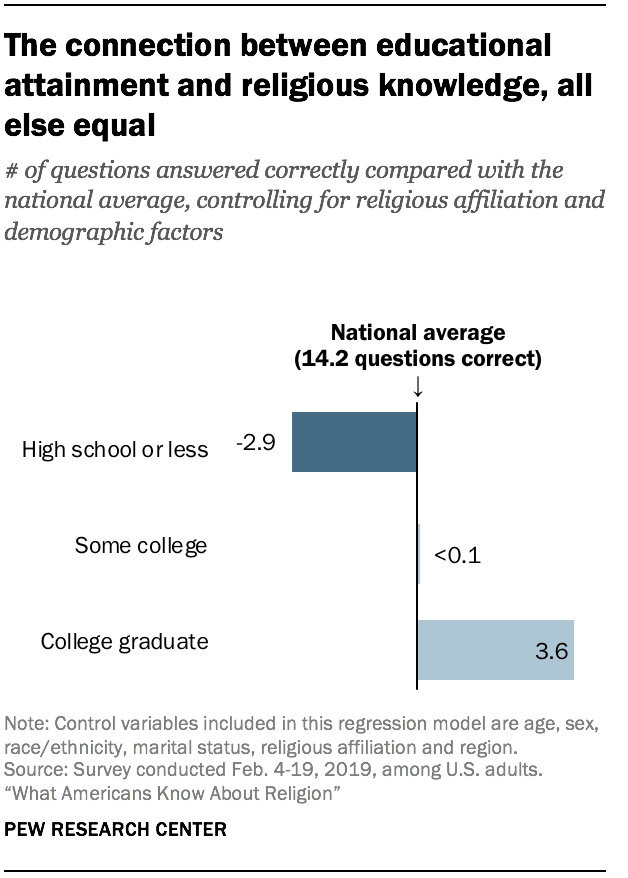

These analyses confirm that educational attainment is among the leading predictors of higher religious knowledge. Having a college degree is associated with an additional 3.6 correct answers than the national average, even after religious affiliation and other demographic characteristics are taken into account. By comparison, having a high school education or less is linked with 2.9 fewer correct answers, on average, than the national average. Thus, with all else held equal, having a college degree makes a difference of 6.5 additional correct answers (out of 32 possible in this survey) compared with someone with a high school education or less.

These analyses confirm that educational attainment is among the leading predictors of higher religious knowledge. Having a college degree is associated with an additional 3.6 correct answers than the national average, even after religious affiliation and other demographic characteristics are taken into account. By comparison, having a high school education or less is linked with 2.9 fewer correct answers, on average, than the national average. Thus, with all else held equal, having a college degree makes a difference of 6.5 additional correct answers (out of 32 possible in this survey) compared with someone with a high school education or less.

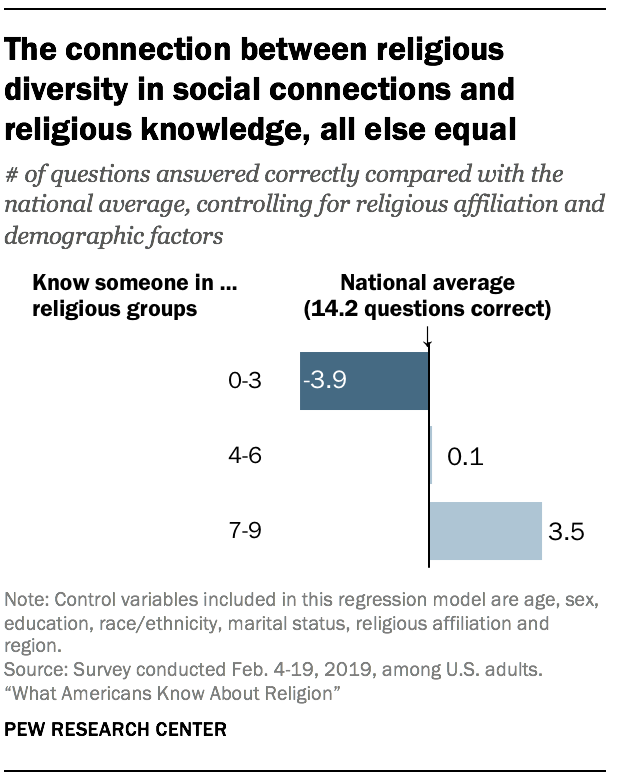

Holding other factors constant, people who have more religiously diverse social networks also tend to answer more religious knowledge questions correctly. For example, those who say they know people from at least seven of the nine religious groups asked about in the survey answer 3.5 more questions right, on average, compared with the national mean. Not only that, but people who know members of just three religious groups or fewer answer an average of 3.9 fewer questions correctly (compared with the national average). That means the difference between knowing people from a large number of religious groups, compared with knowing people in only a few groups, accounts for about seven correct answers on the quiz.

Holding other factors constant, people who have more religiously diverse social networks also tend to answer more religious knowledge questions correctly. For example, those who say they know people from at least seven of the nine religious groups asked about in the survey answer 3.5 more questions right, on average, compared with the national mean. Not only that, but people who know members of just three religious groups or fewer answer an average of 3.9 fewer questions correctly (compared with the national average). That means the difference between knowing people from a large number of religious groups, compared with knowing people in only a few groups, accounts for about seven correct answers on the quiz.

This does not necessarily mean that building social connections with people from many religions directly leads to increased religious knowledge. It could be that people with more religious knowledge are more likely to form these connections in the first place. Yet another possibility is that people who know the most about religion could be more likely to be aware that members of their social circles identify with a variety of faiths. Or it could be a combination of these factors.

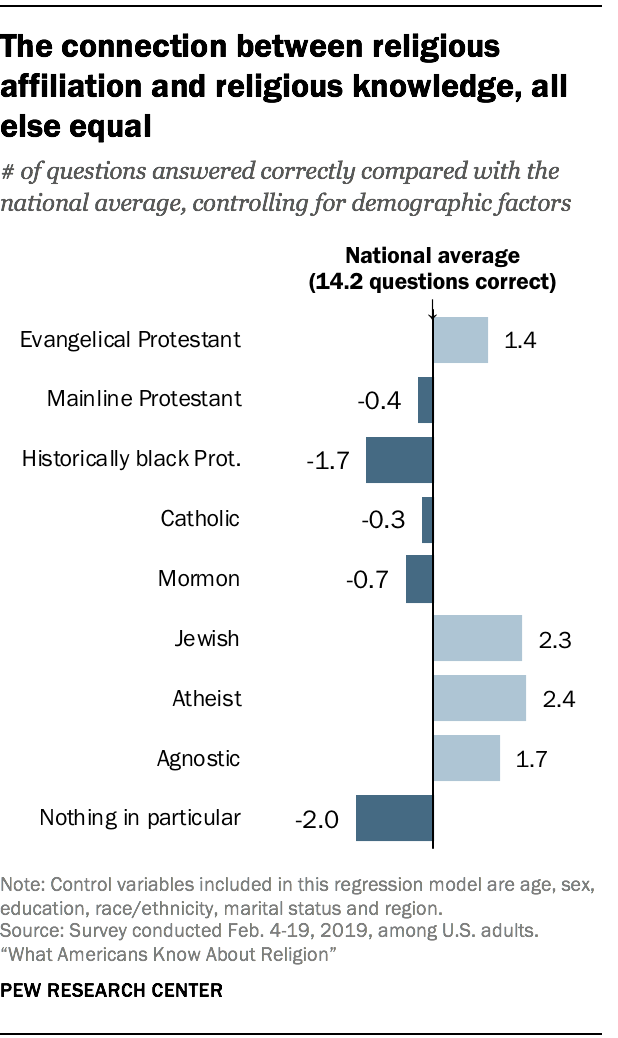

Religious affiliation also remains a good predictor of religious knowledge in these models. Even after education, race and other factors are considered, it is still the case that atheists, Jews, agnostics and evangelical Protestants perform better than other religious groups on this survey. Compared with the national average, atheists get an additional 2.4 questions correct, Jews 2.3 questions, agnostics 1.7 questions and evangelicals 1.4 questions.

Religious affiliation also remains a good predictor of religious knowledge in these models. Even after education, race and other factors are considered, it is still the case that atheists, Jews, agnostics and evangelical Protestants perform better than other religious groups on this survey. Compared with the national average, atheists get an additional 2.4 questions correct, Jews 2.3 questions, agnostics 1.7 questions and evangelicals 1.4 questions.

At the other end of the spectrum, members of the historically black Protestant tradition and those who say their religion is “nothing in particular” trail other groups even after demographic factors are taken into account. Mainline Protestants, Catholics and Mormons fall in the middle and more closely resemble the general public.

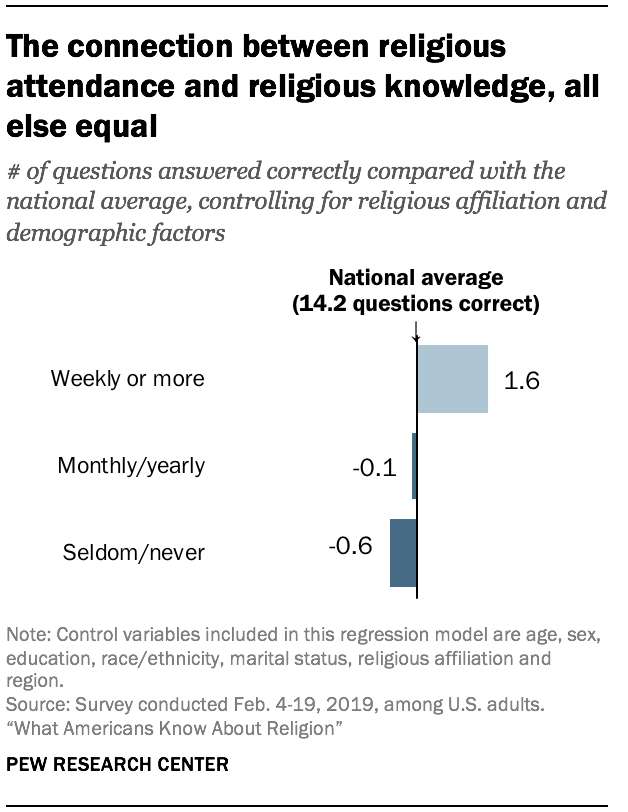

After controlling for other factors (age, sex, education, race and ethnicity, marital status, region, and religious affiliation), those who say they attend religious services at least weekly answer 1.6 more questions correctly than the national average. Those who seldom or never attend religious services correctly answer 0.6 questions fewer, on average, compared with the national average.

After controlling for other factors (age, sex, education, race and ethnicity, marital status, region, and religious affiliation), those who say they attend religious services at least weekly answer 1.6 more questions correctly than the national average. Those who seldom or never attend religious services correctly answer 0.6 questions fewer, on average, compared with the national average.

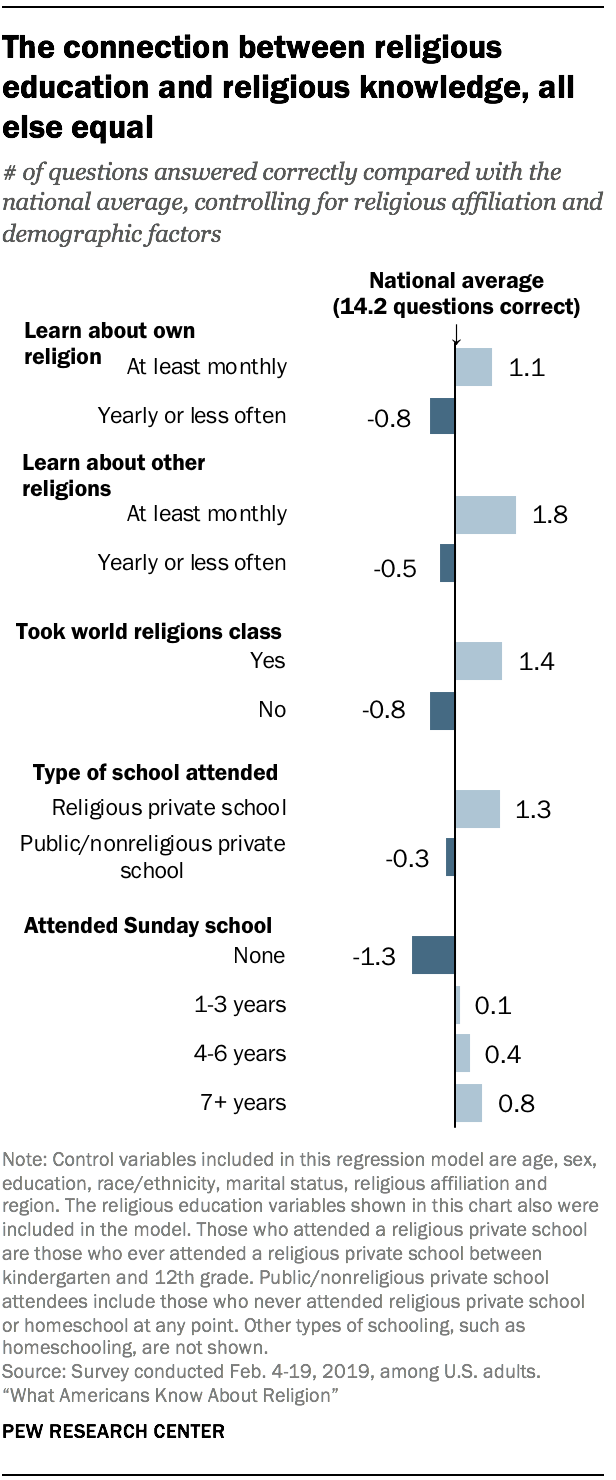

In addition to religious affiliation and demographics, researchers included five measures of religious education in a model: how often respondents spend time learning about their own religion, how often they spend time learning about other religions, whether they have taken a world religions class, what type of school they attended between kindergarten and 12th grade (religious private school or nonreligious public or private school), and how many years they attended Sunday school or similar religious education (if any). All five of these factors were included in the regression model together. Each factor is independently related to religious knowledge.

In addition to religious affiliation and demographics, researchers included five measures of religious education in a model: how often respondents spend time learning about their own religion, how often they spend time learning about other religions, whether they have taken a world religions class, what type of school they attended between kindergarten and 12th grade (religious private school or nonreligious public or private school), and how many years they attended Sunday school or similar religious education (if any). All five of these factors were included in the regression model together. Each factor is independently related to religious knowledge.

Americans who say they do things each month to learn about their own religion – such as reading scripture, visiting websites, listening to podcasts, reading books or magazines, or watching television – correctly answer an average of 1.1 questions more than the national average. By contrast, those who make less frequent efforts to learn about their religion tend to earn below-average scores. Those who regularly do things to learn about other religions (that are not their own) also score higher.

People who have taken a class on world religions get 1.4 more questions right (out of 32) than the national average of 14.2, even after controlling for demographic factors, religious affiliation and other forms of religious education. Those who attended religious private schools as children also perform better, giving an extra 1.3 correct answers than the national average. And people who attended Sunday school, CCD or a similar type of program for many years when growing up get nearly one additional question right.

These relationships hold when looking specifically at the questions about the Bible and Christianity or at the questions about world religions – with one exception. Learning about one’s own religion is not significantly associated with improved knowledge about world religions; rather, learning about one’s own religion is associated only with improved knowledge of topics related to the Bible and Christianity, reflecting the fact that most Americans identify religiously as Christians.18

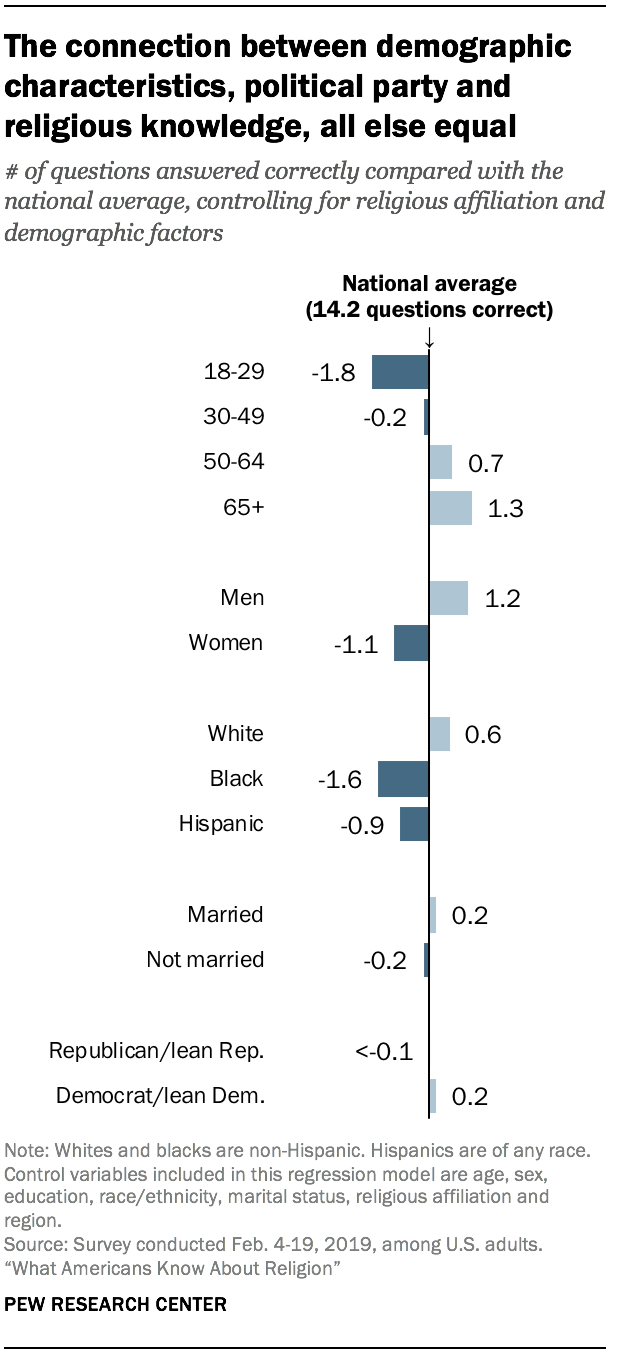

Holding other factors constant, black and Hispanic respondents score significantly lower on the religious knowledge survey than do whites. And women score lower on the quiz than do men. Americans who are 65 or older answer 1.3 additional questions correctly, on average, compared with the national mean, while adults under 30 score 1.8 questions lower than the national average. And those who are currently married get slightly more questions right than those who are not.

Holding other factors constant, black and Hispanic respondents score significantly lower on the religious knowledge survey than do whites. And women score lower on the quiz than do men. Americans who are 65 or older answer 1.3 additional questions correctly, on average, compared with the national mean, while adults under 30 score 1.8 questions lower than the national average. And those who are currently married get slightly more questions right than those who are not.

Once education, race and other factors are considered, Democrats and those who lean toward the Democratic Party answer about as many questions right as do Republicans and Republican leaners.