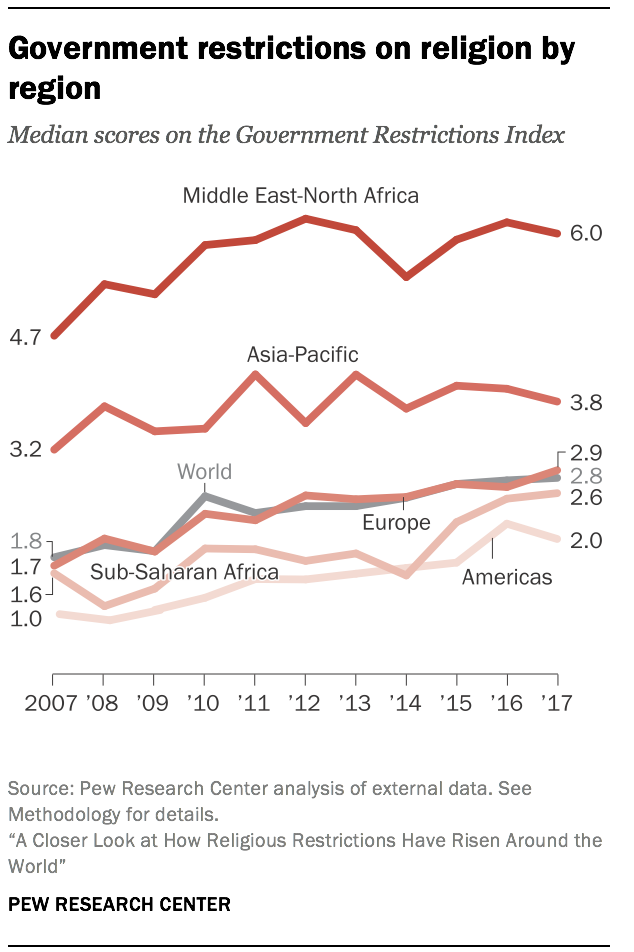

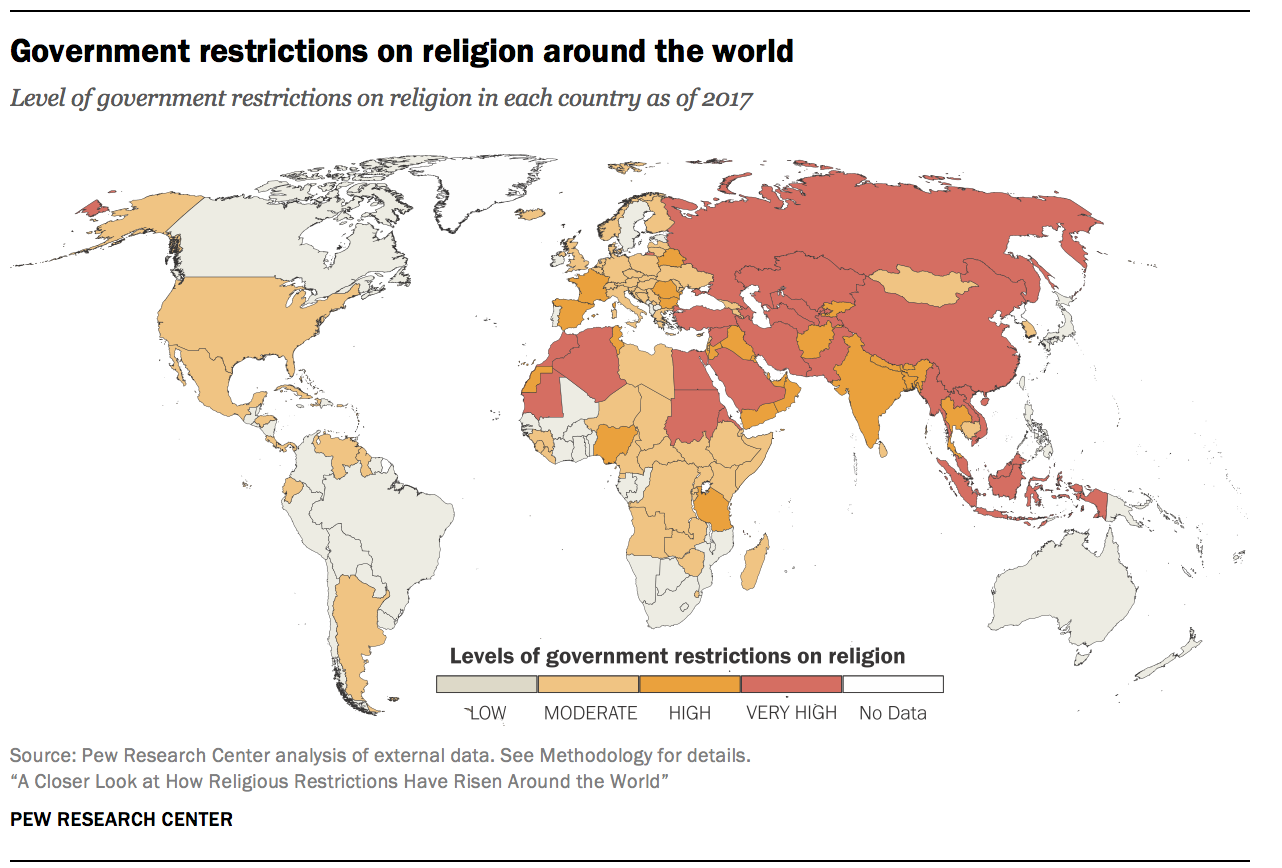

Government restrictions by region

In 2017, the global median score on the Government Restrictions Index (GRI) remained stable at 2.8 – matching 2016 and staying at its highest point since the study began in 2007 (see Overview). The median score declined in three geographic regions (Middle East-North Africa, the Americas and Asia-Pacific), increased in Europe and remained about the same in sub-Saharan Africa.103

In 2017, the global median score on the Government Restrictions Index (GRI) remained stable at 2.8 – matching 2016 and staying at its highest point since the study began in 2007 (see Overview). The median score declined in three geographic regions (Middle East-North Africa, the Americas and Asia-Pacific), increased in Europe and remained about the same in sub-Saharan Africa.103

The Middle East-North Africa region continued to have the highest level of government restrictions on religion out of all regions. The median score for the 20 countries (6.0) in 2017 was more than double the global median (2.8), which has been the case every year since 2007. Since 2016, there has been a small decline (0.2 points) in the Middle East’s median score, partly due to fewer reports of government hostility toward minority religious groups (down from 15 countries in 2016 to 12 in 2017).

The Asia-Pacific region had the second-highest level of restrictions. Similar to the Middle East, the median score among the 50 countries in the region (3.8) also declined by 0.2 points, and there were fewer Asian countries where governments used physical violence toward minority groups (23 countries in 2016 vs. 20 in 2017). However, in 2017, there were still 10 countries in the Asia-Pacific region where there were 200 or more cases of governments using force (including detentions and killings) against religious groups. For example, in Uzbekistan, the country’s president in 2017 pardoned 763 prisoners of conscience who were being held for their religious beliefs, but a civil society organization reported that the government still held 7,000 “religious prisoners.”104

Europe experienced a slight increase in its median score, from 2.7 to 2.9, marking the highest levels of government restrictions for the region since the study began in 2007 and the only increase out of the five regions in 2017. More specifically, there was a notable rise in governments failing to intervene when religious groups were targeted. For example, in Croatia and Moldova, Jewish leaders reported dissatisfaction with the government’s handling of anti-Semitic incidents, including failure to respond to vandalism and hate speech. In Moldova, authorities also failed to prosecute threats and verbal attacks on Jehovah’s Witnesses.105 And in Greece, the government reportedly did not respond to two separate attacks on churches in Athens by anarchists. In one incident, the anarchist group set fire to Saint Basil Church and named its opposition to the church’s sexism and stance on homosexuality as a reason for the attack.106

There also was an increase in the number of governments in Europe (from 17 to 20) that regulated religious clothing in some way. For example, Austria enacted a ban on full-face veils in public spaces that went into effect in October of 2017.107 And in Germany, the federal parliament implemented a ban on soldiers and civil servants wearing full-face coverings.108

Sub-Saharan Africa’s median GRI score stayed about the same (2.6) and remained the highest median score for the region since 2007. Governments continued to restrict women’s religious dress in several countries (see Overview for more details). For example, in Liberia, Muslim women reported that they were not allowed to register to vote by election officials if they did not remove their headscarves for voter identification photos, but said Catholic nuns and other women wearing traditional head wraps were permitted to wear their head coverings for their photos.109

The Americas’ median score declined slightly (from 2.2 to 2.0) since 2016, when the median level of government restrictions had reached an all-time high. By 2017, there were fewer countries (seven, down from 10 in 2016) where governments used some level of force — such as detentions, physical abuse or killings — toward religious groups. There also was a decline in the number of countries (from six to three) where governments failed to protect religious groups in the face of discrimination and abuse.

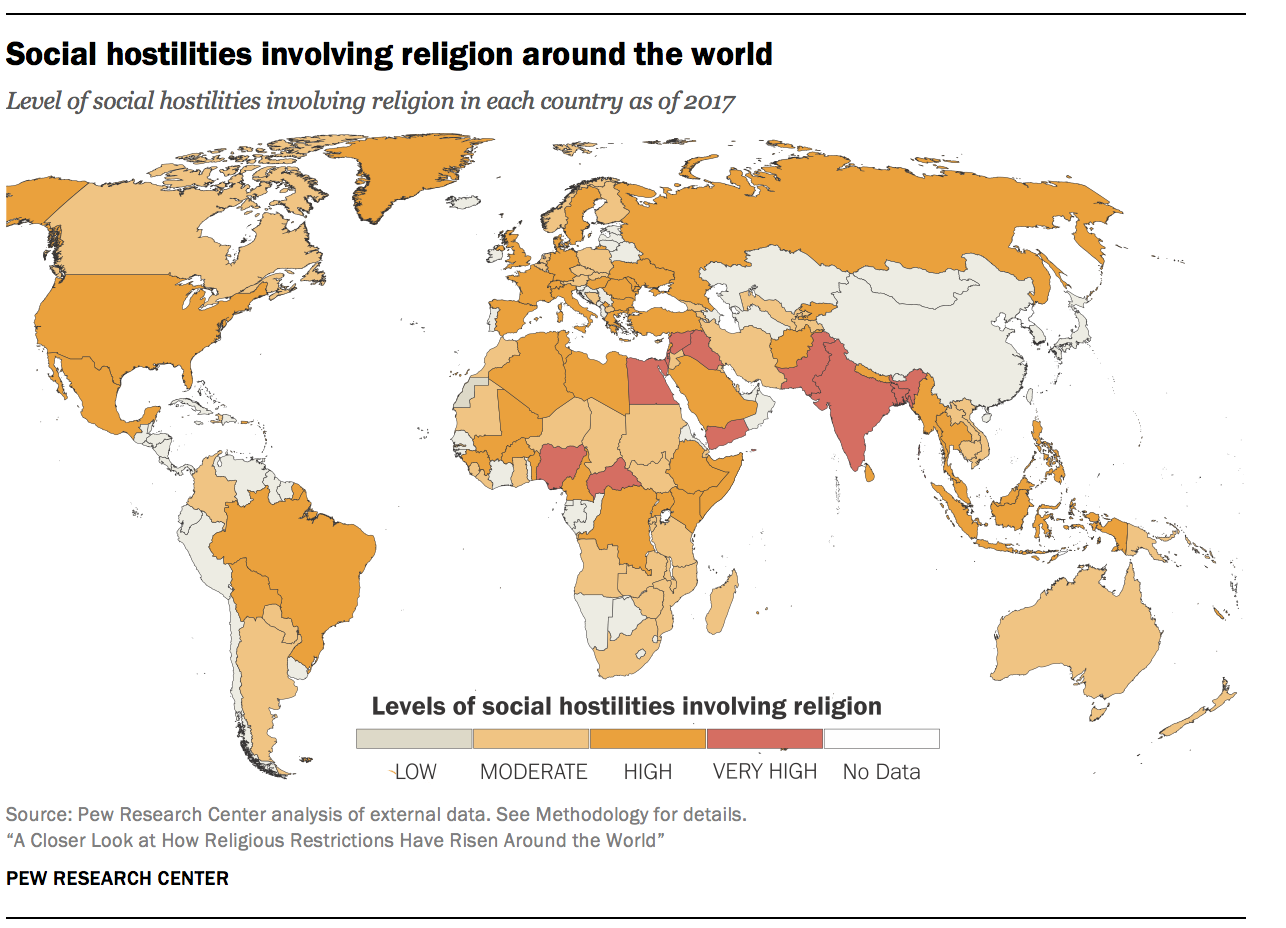

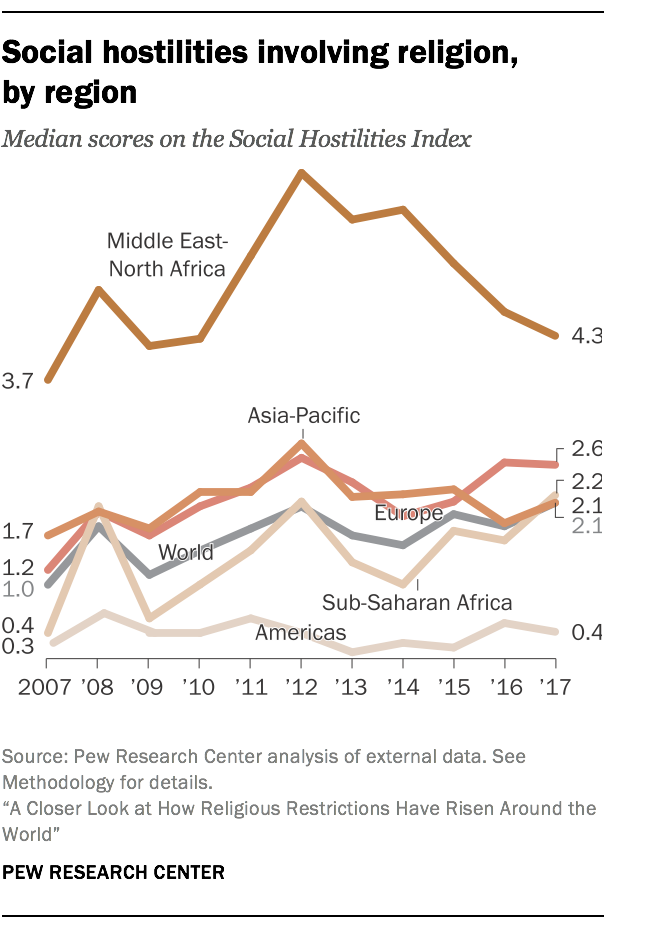

Social hostilities by region

The global median score on the Social Hostilities Index (SHI) increased from 1.8 in 2016 to 2.1 in 2017, the highest level reported since the baseline year of the study (2007). Two regions had increases in their scores (Asia-Pacific and sub-Saharan Africa), one had a decrease (Middle East-North Africa), and two regions held steady (Europe and the Americas).110

The Middle East and North Africa remained the region with the highest median level of social hostilities (4.3), more than double the global median (2.1). However, the median score for the 20 countries in the region declined from 4.6 in 2016 — continuing a trend from the previous year — and remains well below the all-time peak of 6.4 in 2012, following the Arab Spring. The modest decline in 2017 was partly due to fewer reported cases of religious groups attempting to prevent other groups from operating and fewer hostilities over conversions.

The Middle East and North Africa remained the region with the highest median level of social hostilities (4.3), more than double the global median (2.1). However, the median score for the 20 countries in the region declined from 4.6 in 2016 — continuing a trend from the previous year — and remains well below the all-time peak of 6.4 in 2012, following the Arab Spring. The modest decline in 2017 was partly due to fewer reported cases of religious groups attempting to prevent other groups from operating and fewer hostilities over conversions.

Europe’s median SHI score remained stable at 2.6 – the second-highest out of all regions. Organized groups (such as neo-Nazi groups) continued to attempt to dominate public life with their perspective on religion in 33 out of 45 countries in the region.

Sub-Saharan Africa’s median level of social hostilities increased from 1.6 in 2016 to 2.2 in 2017, the largest rise out of all regions. There was a notable increase in groups using violence or the threat of violence to enforce religious norms (see Overview for more details), as well as increased hostilities over conversions and proselytizing in the region. In addition, in a growing number of countries (from 15 in 2016 to 20 in 2017), religious groups sought to prevent other groups from being able to operate. For example, in Mauritania, during Eid prayers, the imam of the Grand Mosque of Nouakchott issued a warning against the growing threat of Shiite Islam and encouraged the government to cut ties with Iran to curb the spread of Iranian Shiite Islam.111

Sub-Saharan Africa also had the only country in the study (Mali) to have a large increase in its score (see Chapter 1 for details). And another country in the region — the Central African Republic — experienced an escalation in clashes between armed groups divided along religious and ethnic lines, prompting a United Nations official to warn that early signs of genocide were present.112

In Asia and the Pacific, the median SHI score rose from 1.8 to 2.1, mirroring the global median score. There were reported increases in sectarian violence in the region. In Pakistan, Shiites were targeted several times by the militant group Lashkar-e-Jhangvi and the Pakistani Taliban, including two attacks in January 2017 that left more than 80 people dead.113 And in Burma (Myanmar), Buddhist nationalists and monks attacked Christian converts and Muslims during the year.114

Out of all five regions, the Americas remained at the lowest level of social hostilities in 2017, with a median SHI score of 0.4.