Countries with the most extensive government restrictions on religion

Most countries around the world have some form of restrictions on religion – whether it is through laws that limit actions like public preaching or conversion, or actions that can include detaining, displacing or assaulting members of religious groups.

Most countries around the world have some form of restrictions on religion – whether it is through laws that limit actions like public preaching or conversion, or actions that can include detaining, displacing or assaulting members of religious groups.

A subset of countries, however, has particularly high levels of government restrictions on religion. Twenty-five of the 198 countries in this study had “very high” levels of government restrictions on religion in 2016, up from 23 countries in 2015 and just 16 in 2014.26 This marks the biggest number of countries to fall in this top category since Pew Research Center began analyzing restrictions on religion in 2007.

Three countries and territories – Laos, Burma (Myanmar) and Western Sahara – moved into the “very high” category in 2016, while one country – Vietnam – dropped from the “very high” to the “high” restrictions category. Burma’s score was affected by ongoing government actions taken against the Rohingya Muslim minority, described by the United Nations as “crimes against humanity.”27 In response to deadly attacks in October and November, Burmese military and police forces conducted “security operations” that allegedly resulted in extrajudicial killings, rapes, beatings and mass arrests in northern Rakhine State. The operations resulted in the displacement of approximately 93,000 civilians, according to the United Nations.28

Vietnam’s slightly lower government restrictions score (from a 6.6 in 2015 to a 6.5 in 2016) was due in part to the Vietnamese government no longer requiring religious affiliation to be listed on identification cards. Previously, individuals who wished to change their religious affiliation had to go through a cumbersome process and were, in some cases, prevented from doing so by local authorities.29 For a complete list of all countries in each category, see the Government Restrictions Index table in Appendix A.30

Countries with the most extensive social hostilities involving religion

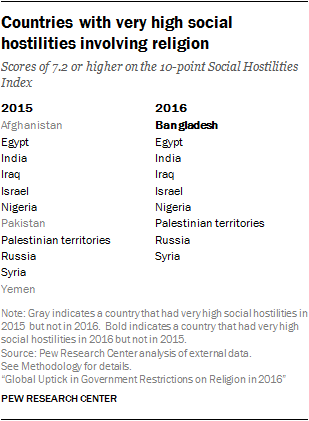

In contrast to the increase in countries with very high government restrictions on religion, fewer countries fell into the highest category of social hostilities in 2016. Nine countries had “very high” levels of social hostilities involving religion in 2016, a slight decrease from 11 in 2015. These social hostilities included actions like social groups harassing members of a certain religion, as well as organized groups attempting to dominate public life with their perspective on religion (for more on this latter type of activity, see Overview).31

In contrast to the increase in countries with very high government restrictions on religion, fewer countries fell into the highest category of social hostilities in 2016. Nine countries had “very high” levels of social hostilities involving religion in 2016, a slight decrease from 11 in 2015. These social hostilities included actions like social groups harassing members of a certain religion, as well as organized groups attempting to dominate public life with their perspective on religion (for more on this latter type of activity, see Overview).31

Bangladesh was the only country to join this category, due in part to an increase in assaults and killings of members of religious groups by social groups or individuals. In multiple instances in 2016 – continuing a pattern from previous years – people who had expressed atheist views or were accused of offending Islam on the internet were killed or threatened.32 Meanwhile, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Yemen all fell out of the “very high” category of social hostilities involving religion. While these countries all continued to experience religion-related violence at high levels, small changes in reported incidents from year to year, as well as methodological adjustments, accounted for movement across categories.33 In Afghanistan, for instance, the Taliban still targeted religious minorities and other civilians, but sources did not report major incidents of mob violence, which had occurred in 2015.34 Pakistan saw a small decrease (0.4 points) in its social hostilities score due to a reduction in the number of displacements caused by religion-related conflict and terrorism.35

The total number of countries with “moderate” levels of social hostilities was unchanged from 2015 to 2016. Similarly, the “low” and “high” categories were also mostly stable in size, although some countries did move into and out of each of these categories.

For example, Benin jumped from the “low” to “high” in social hostilities in 2016. In contrast with the previous year, sources reported conflicts between Voodoo practitioners and the Catholic Church in 2016; in May, for instance, a Catholic prayer center was vandalized by a group of Voodoo followers who accused the local chaplain of angering their deity and counteracting their rituals.36

For a complete list of all countries in each category, see the Social Hostilities Index table in Appendix B.37

Changes in government restrictions on religion

Tracking the countries that enter or exit the “very high” category of religious restrictions is useful for observing changes from year to year, but sometimes countries can have substantial changes in scores that do not necessarily cause them to move into or out of the highest category. For this reason, Pew Research Center analyzes the magnitude of changes across all countries and categories to provide greater insight into how government actions and policies can have an especially large impact on religious restrictions each year.

Tracking the countries that enter or exit the “very high” category of religious restrictions is useful for observing changes from year to year, but sometimes countries can have substantial changes in scores that do not necessarily cause them to move into or out of the highest category. For this reason, Pew Research Center analyzes the magnitude of changes across all countries and categories to provide greater insight into how government actions and policies can have an especially large impact on religious restrictions each year.

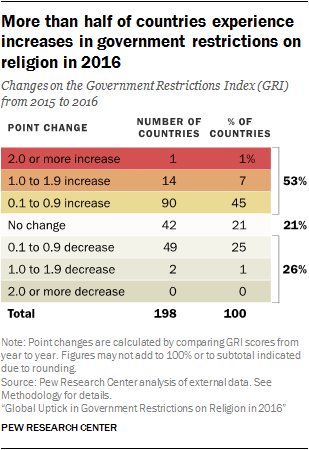

Overall, between 2015 and 2016, regardless of the size of the change, more than twice as many countries had increases as had decreases in their Government Restrictions Index (GRI) scores (105 countries vs. 51 countries).

Gambia was the only country to experience a large change (2.0 points or more) on the Government Restrictions Index (GRI) in 2016. Its score increased to 3.8 from 1.7 in 2015 (bumping it from the “low” to the “moderate” category), due in part to restrictions on public preaching and religious dress. In February, the government-sponsored Supreme Islamic Council said it would ensure that Islamic scholars adhere to the acceptable principles of Islam by screening and certifying all of those who wanted to preach on local media.38 In addition, early in 2016, President Yahya Jammeh issued an executive decree that required female government employees to wear headscarves to work. The decree was rescinded a week later after criticism from opposition parties and the media.39 Still, this decree followed a presidential announcement by Jammeh in late 2015 declaring Gambia an Islamic state – a claim he reiterated in July 2016.

Sixteen countries experienced modest changes (1.0 to 1.9 points) in their GRI scores, and among those, far more saw increases in scores (14 countries) than decreases (Albania and Equatorial Guinea). In Albania, the decrease was due in part to the resolution of a 2014 case that involved a Muslim girl barred from attending a public school because she started wearing a headscarf. The action was ruled as discriminatory.40

Among the 14 countries with modest increases, Ethiopia and the Maldives had some of the largest jumps in GRI scores. In Ethiopia, the government declared a six-month state of emergency in October 2016, limiting religious freedoms.41 And in the Maldives, a new “Anti-Defamation and Freedom of Expression” law stipulated that religious preaching or teaching of Islam must be in accordance with the 1994 Religious Unity Act, which criminalizes statements or actions that disrupt religious unity.42

Most countries experienced only small changes (less than 1.0 point) in their GRI scores. Of the 198 countries analyzed, 49 (25%) had a small decrease and 90 (45%) had a small increase. An additional 42 countries had no change at all.

Changes in social hostilities involving religion

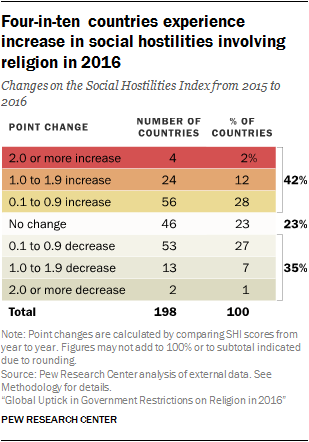

In 2016, four countries experienced large increases (2.0 points or more) in their SHI scores, while just two – Niger and the Republic of the Congo – saw large decreases in their scores. In Niger, cooperation between Christian and Muslim communities reportedly improved after violent protests in 2015.43 And in the Republic of the Congo, Muslim leaders said they had not received reports of harassment against the Muslim community, as opposed to in 2015, when authorities arrested several people attempting to vandalize a mosque.44

In 2016, four countries experienced large increases (2.0 points or more) in their SHI scores, while just two – Niger and the Republic of the Congo – saw large decreases in their scores. In Niger, cooperation between Christian and Muslim communities reportedly improved after violent protests in 2015.43 And in the Republic of the Congo, Muslim leaders said they had not received reports of harassment against the Muslim community, as opposed to in 2015, when authorities arrested several people attempting to vandalize a mosque.44

Benin, Mexico, Sierra Leone and Ukraine had large increases in their scores. In Sierra Leone, there were several documented incidents of what religious leaders called “aggressive proselytization,” raising concerns that Christian and Muslim fundamentalist groups would threaten religious harmony in the country.45 And in Ukraine, in addition to ongoing tensions between the Ukrainian Orthodox Church-Moscow Patriarchate and the Ukrainian Orthodox Church-Kyiv Patriarchate, Russian-backed separatists in the eastern part of the country seized houses of worship for Jehovah’s Witnesses as well as a Seventh-day Adventist church.46

Thirty-seven countries had modest changes (1.0 to 1.9 points) in their SHI scores, with 24 experiencing a modest increase and 13 a modest decrease. Timor-Leste, for example, saw a modest decrease in social hostilities as there were no reported incidents of mob violence. The prior year, a group led by a Catholic priest destroyed a church being constructed by a Protestant group 47

Similar to the changes in the GRI index, most countries experienced only small changes in their SHI scores. Among the 109 countries that had small changes, about half (53 countries) had a decrease while the other half (56 countries) experienced an increase.

Changes in overall restrictions on religion

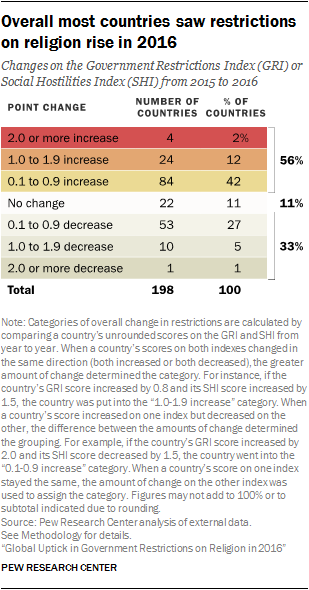

Analyzing changes in government restrictions on religion and social hostilities involving religion together provides a picture of the overall condition of religious restrictions in a country, whether perpetrated by government actors or social groups and individuals.

Analyzing changes in government restrictions on religion and social hostilities involving religion together provides a picture of the overall condition of religious restrictions in a country, whether perpetrated by government actors or social groups and individuals.

Far more countries experienced increases in overall scores rather than decreases in 2016. Among the 112 countries with an increased score, three-quarters (75%) had only small increases. About one-in-five (21%) saw modest increases in scores, while 4% had large increases in overall restrictions on religion.

Nearly a third of countries (64 countries) experienced decreases in overall restrictions on religion. Most of them (83%) had small decreases in scores, while 16% had modest decreases and only one country – Niger – had a large decrease in overall restrictions on religion.

Twenty-two countries had no change in their overall score between 2015 and 2016.