Five hundred years after the start of the Protestant Reformation, a new Pew Research Center survey finds that U.S. Protestants are not united about – and in some cases, are not even aware of – some of the controversies that were central to the historical schism between Protestantism and Catholicism.

Indeed, half a millennium after fundamental disagreements over the means of salvation and the authority of the Bible (among other topics) sparked a series of bloody wars between Protestants and Catholics in Europe, most American Protestants now say the two Christian traditions are more similar than different, religiously, and many U.S. Protestants espouse traditionally Catholic beliefs on some issues.

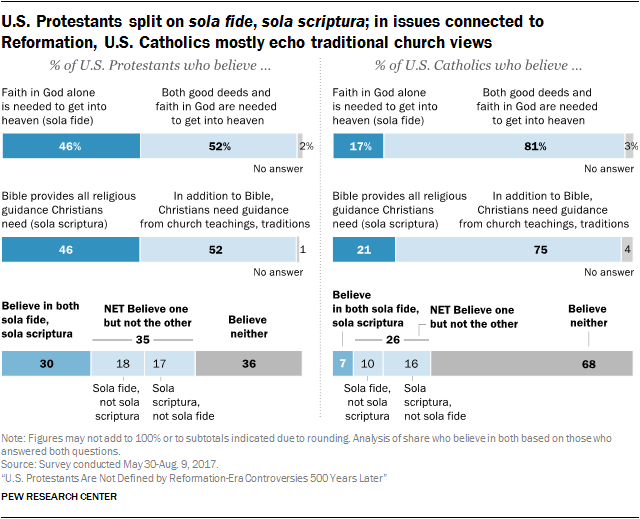

For example, nearly half of U.S. Protestants today (46%) say faith alone is needed to attain salvation (a belief held by Protestant reformers in the 16th century, known in Latin as sola fide). But about half (52%) say both good deeds and faith are needed to get into heaven, a historically Catholic belief.

U.S. Protestants also are split on another issue that played a key role in the Reformation: 46% say the Bible is the sole source of religious authority for Christians – a traditionally Protestant belief known as sola scriptura. Meanwhile, 52% say Christians should look both to the Bible and to the church’s official teachings and tradition for guidance, the position held by the Catholic Church during the time of the Reformation and today.

When these two questions are combined, the survey shows that just three-in-ten U.S. Protestants believe in both sola fide and sola scriptura. One third of Protestants (35%) affirm one but not the other, and 36% do not believe in either sola fide or sola scriptura.

While Protestants are divided on how salvation is attained and whether the Bible is the sole source to which Christians should look for religious guidance, U.S. Catholics mostly align with the teachings of the Catholic Church. Fully eight-in-ten U.S. Catholics say both good deeds and faith are needed to get into heaven. And three-quarters say that in addition to the Bible, Christians need guidance from church teachings and tradition. Overall, two-thirds of Catholics take the traditional positions of the church on both of these issues.

The 500th anniversary of the Reformation is being commemorated in 2017 largely because Oct. 31, 1517, is the date on which Martin Luther legendarily nailed his 95 theses to the door of All Saints Church in Wittenberg, Germany. Some scholars now doubt that Luther actually nailed his long list of theological propositions to the church door, and the notion that the Reformation began on a particular day – or even in a single year – is an obvious oversimplification. Many historians argue that the Reformation is best understood as a series of events with roots that precede Luther and which continued into the 17th century, long after his death in 1546.

Furthermore, the issues at the heart of the Reformation were not merely doctrinal. Disputes also arose over religious practices, ecclesiastical structures, the sale of indulgences, the expensive construction of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, and more. Political and other factors also played an important role. But sola fide and sola scriptura, the convictions that faith alone leads to salvation in heaven and that the Bible is the sole source of legitimate authority for Christian believers, became the rallying cry for many Protestant reformers. As Yale University Professor Carlos M.N. Eire has written: “The two principles alone do not explain the whole of Luther’s theology, but it is impossible to understand Luther and the whole Protestant Reformation without them.”1

The survey finds that belief in sola fide and sola scriptura is much more prevalent among white evangelical Protestants in the U.S. than among white mainline Protestants or black Protestants. Indeed, fully two-thirds of white evangelicals say they believe faith alone is the key to eternal salvation, and nearly six-in-ten say the Bible is the only source to which Christians should look for religious guidance. Even among white evangelicals, however, just 44% express both convictions; 37% believe one but not the other, while 19% of self-identified white evangelicals do not embrace either sola fide or sola scriptura.

These are among the main findings of a new survey, conducted May 30 to Aug. 9, 2017, among participants in Pew Research Center’s nationally representative American Trends Panel. In addition to exploring American beliefs about sola fide and sola scriptura, the survey also included several questions about knowledge of the Reformation and about perceptions of whether Protestantism and Catholicism today are more alike or different.

Most Protestants in the survey (70%) correctly identified “the Reformation” as the term commonly used to refer to the historical period in which Protestants broke away from the Catholic Church. And a similar share (71%) picked Martin Luther when asked to identify the name of the person whose writings and actions inspired the Protestant Reformation. Still, significant minorities of Protestants answered these multiple-choice questions incorrectly. Nearly one-in-five, for instance, named “the Great Crusade” as the term for the period in which Protestants and Catholics split, while 3% chose “the Great Schism” and another 3% said they thought “the French Revolution” was the name of that historical period.

And when asked which religious group traditionally teaches that salvation comes through faith alone (only Protestants, only Catholics, both or neither), just one-quarter of U.S. Protestants correctly answered “only Protestants” (27%). A plurality of Protestants (44%) say both Protestantism and Catholicism teach sola fide, while 19% say neither tradition teaches this and 8% say only Catholicism holds that salvation comes through faith alone.

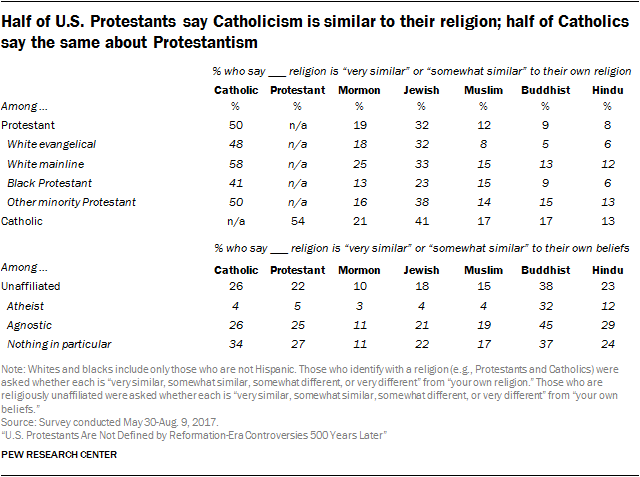

The new survey also shows that majorities of both Protestants and Catholics in America say the two traditions are, religiously, “more similar than they are different.” About two-thirds of Catholics (65%) take this position, as do 57% of Protestants (including 67% of white mainline Protestants). Respondents were asked an additional question about how similar certain religions are to their own faith. Roughly half of both Protestants and Catholics say that the other tradition is at least somewhat similar to their own, while fewer say the same about other religions such as Judaism, Mormonism and Islam.

The new survey also shows that majorities of both Protestants and Catholics in America say the two traditions are, religiously, “more similar than they are different.” About two-thirds of Catholics (65%) take this position, as do 57% of Protestants (including 67% of white mainline Protestants). Respondents were asked an additional question about how similar certain religions are to their own faith. Roughly half of both Protestants and Catholics say that the other tradition is at least somewhat similar to their own, while fewer say the same about other religions such as Judaism, Mormonism and Islam.

Pew Research Center also asked Catholics and Protestants in Western Europe about their opinions on issues related to the Protestant Reformation, including some of the same questions that were asked in the United States. The results of the Western Europe survey can be found here.

Reformation beliefs: Protestants mostly reject belief in purgatory, but divided over sola fide and sola scriptura

One issue that split Protestants and Catholics during the Reformation was disagreement over whether Christians attain salvation in heaven through faith in God alone, or through a combination of faith and good works. Generally speaking, Martin Luther and other Protestant reformers in the 16th century espoused the belief that salvation is attained only through faith in Jesus and his atoning sacrifice on the cross (sola fide), while Catholicism taught that salvation comes through a combination of faith plus good works (e.g., living a virtuous life and seeking forgiveness for sins).2

One issue that split Protestants and Catholics during the Reformation was disagreement over whether Christians attain salvation in heaven through faith in God alone, or through a combination of faith and good works. Generally speaking, Martin Luther and other Protestant reformers in the 16th century espoused the belief that salvation is attained only through faith in Jesus and his atoning sacrifice on the cross (sola fide), while Catholicism taught that salvation comes through a combination of faith plus good works (e.g., living a virtuous life and seeking forgiveness for sins).2

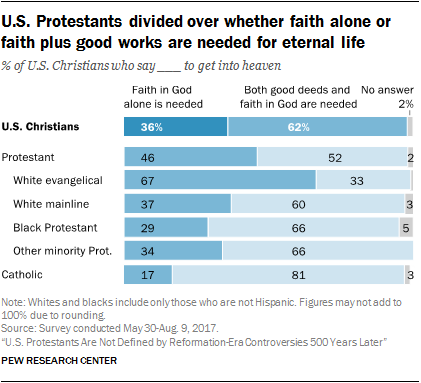

Today, most Christians in the U.S. (62%) say that both faith in God and good deeds are necessary to get into heaven. Fully eight-in-ten Catholics (81%) hold this view, but so do majorities of white mainline Protestants (60%), black Protestants (66%) and other minority Protestants (66%).

White evangelicals are the only Protestant subgroup analyzed in the survey in which most take the opposite position. Two-thirds of white evangelicals (67%) say salvation comes through faith alone, while 33% say that both faith and good works are needed for salvation.3

The survey finds a similar pattern in response to a question about sola scriptura, the idea (held by Protestant reformers) that the Bible is the sole source of religious authority for Christians. Catholicism, by contrast, holds that Christians should look both to the Bible and to church teachings and traditions for guidance.4

The survey finds a similar pattern in response to a question about sola scriptura, the idea (held by Protestant reformers) that the Bible is the sole source of religious authority for Christians. Catholicism, by contrast, holds that Christians should look both to the Bible and to church teachings and traditions for guidance.4

Most U.S. Christians (60%) do not accept the idea that the Bible can be the sole source of religious guidance for Christians, saying instead that in addition to scripture, Christians also need religious guidance from church teachings and traditions. The view that both the Bible and church traditions are necessary for guidance is expressed by most Catholics (75%), black Protestants (67%) and white mainline Protestants (61%).

The balance of opinion among white evangelical Protestants leans in the other direction: 58% say the Bible does indeed provide all the religious guidance Christians need, while 41% say guidance from the Bible must be supplemented by church teachings and traditions.5

Taken together, just three-in-ten U.S. Protestants believe in both sola fide and sola scriptura. Belief in both teachings is most common among white evangelical Protestants, among whom 44% affirm that salvation comes through faith alone and that the Bible is the sole authority to which Christians should look for religious guidance.

Two-thirds of Catholics reject both sola fide and sola scriptura, saying instead that salvation depends on faith and good works and that Christians need religious guidance from both the Bible and church traditions and teachings.

Another theological sticking point between Protestants and Catholics centered on purgatory, the Catholic teaching (rejected by many Protestant reformers) that after death, the souls of some people undergo a period of “purgation,” or cleansing, of their sins before entering heaven.6

Another theological sticking point between Protestants and Catholics centered on purgatory, the Catholic teaching (rejected by many Protestant reformers) that after death, the souls of some people undergo a period of “purgation,” or cleansing, of their sins before entering heaven.6

In the U.S. today, seven-in-ten Catholics say they believe in purgatory. Black Protestants are closely divided on this question. By contrast, most white evangelical Protestants (72%) and white mainline Protestants (66%) say they do not believe in purgatory.7

The survey finds that among white evangelical Protestants, higher levels of religious observance and educational attainment are linked with greater acceptance of the teachings of Protestant Reformation leaders. For example, eight-in-ten white evangelicals who say they attend church on a weekly basis say salvation comes through faith alone, compared with 54% among evangelicals who attend church less regularly. And whereas 72% of white evangelical college graduates say the Bible provides all the religious guidance Christians need, just 53% of evangelicals with less education say this.8

Among Catholics, these patterns are not always clear. Catholic college graduates, however, are somewhat more likely than Catholics with less education to espouse the traditionally Catholic position that salvation comes through a combination of faith and good works.

In their own words: What determines whether a person gains eternal life?

While some Christian respondents in the survey were asked a multiple-choice question about what is needed to get to heaven – and given “faith in God is the only thing” and “both good deeds and faith in God” as response options – others were asked to answer the question in their own words. This approach elicited a variety of responses, providing a different way of looking at Christians’ views on this topic.

On the forced-choice question, U.S. Christians lean toward “both good deeds and faith in God” as key to getting into heaven (62%). But when presented with the open-ended question, Christians are more evenly divided: 46% gave responses that fit into the broad category of actions, while a similar share (43%) mentioned beliefs as the key to eternal life. (Respondents had the option to give multiple responses, but most did not.)

Generally being a good person and asking forgiveness for sins were among the most common actions mentioned as key to getting into heaven; other Christians in this category said that following the “golden rule” or God’s will is how one gains eternal life. When it comes to beliefs, Christians most commonly cited “belief in Jesus Christ” or “belief in God” as crucial to salvation.

White evangelical Protestants were more likely than any other religious group to say beliefs determine whether a person gains eternal life. Fully two-thirds of white evangelicals said belief in Jesus or having a personal relationship with Jesus is the key to gaining eternal life. According to one white evangelical Protestant respondent, “whether or not they have accepted Jesus as their personal savior” determines whether one will gain eternal life in heaven.

Catholics, meanwhile, were especially likely to suggest that good actions are what lead to eternal life (60%). Three-in-ten Catholics, for example, said being a good person will lead to eternal life (32%), and 14% mentioned treating others nicely or as you would like to be treated. In the words of one Catholic respondent, “treating people with respect and how you would want to be treated and praying to the Lord for forgiveness for your sins” determines who will go to heaven.

Knowledge about the Reformation: Most know about Martin Luther and recognize the term ‘Protestant,’ fewer know sola fide is a Protestant belief

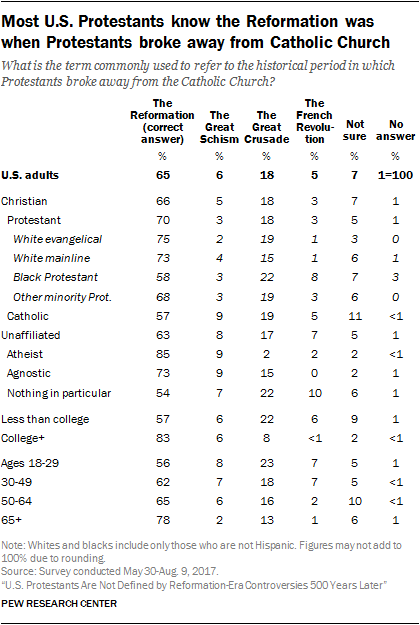

To gauge Americans’ knowledge about the Reformation, the survey asked a series of multiple-choice questions, each with one historically accurate response. When asked to identify “the term commonly used to refer to the historical period in which Protestants broke away from the Catholic Church,” two-thirds of the general public (65%) correctly chose the Reformation. About one-in-five (18%) chose “the Great Crusade,” while 6% said “the Great Schism” and 5% said “the French Revolution.”

To gauge Americans’ knowledge about the Reformation, the survey asked a series of multiple-choice questions, each with one historically accurate response. When asked to identify “the term commonly used to refer to the historical period in which Protestants broke away from the Catholic Church,” two-thirds of the general public (65%) correctly chose the Reformation. About one-in-five (18%) chose “the Great Crusade,” while 6% said “the Great Schism” and 5% said “the French Revolution.”

Similar shares of U.S. Christians (66%) and religiously unaffiliated Americans (63%) answered this question correctly, with self-identified atheists (85%) doing especially well.

But within Christianity, there were some major differences. Protestants (70%) – especially white evangelical Protestants (75%) and white mainline Protestants (73%) – were more likely than Catholics (57%) to identify the Reformation correctly.9

Roughly eight-in-ten college-educated adults (83%) and adults over the age of 65 (78%) correctly said the Reformation is the term for the historical period when Protestants broke away from Catholicism. By comparison, 57% of adults without a college degree and 56% of adults under 30 correctly answered this question.

Respondents were also asked: “What was the name of the person whose writings and actions inspired the Protestant Reformation?” Fully two-thirds of the general public (67%) correctly chose Martin Luther. Fewer said John Wesley (16%) or Thomas Aquinas (10%), while 6% said they were unsure who inspired the Protestant Reformation.

Respondents were also asked: “What was the name of the person whose writings and actions inspired the Protestant Reformation?” Fully two-thirds of the general public (67%) correctly chose Martin Luther. Fewer said John Wesley (16%) or Thomas Aquinas (10%), while 6% said they were unsure who inspired the Protestant Reformation.

Majorities of adults across all major Christian and unaffiliated subgroups correctly identified Martin Luther as the person who inspired the Protestant Reformation.10

Fully eight-in-ten college graduates correctly chose Martin Luther, compared with roughly six-in-ten adults (62%) who have less than a college education.

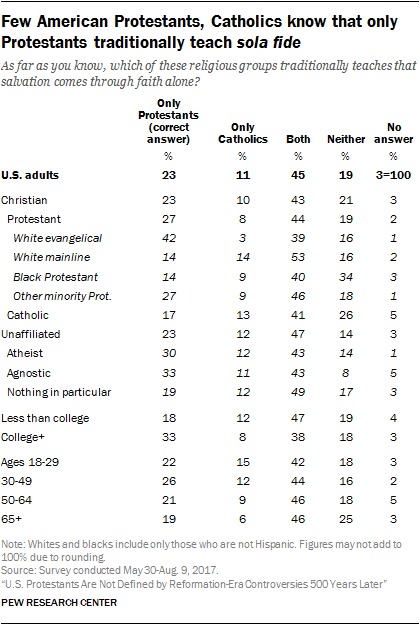

Far fewer U.S. adults identified the religious group that traditionally teaches that salvation comes through faith alone. (Respondents were given a list of four options: only Protestants, only Catholics, both or neither).

Far fewer U.S. adults identified the religious group that traditionally teaches that salvation comes through faith alone. (Respondents were given a list of four options: only Protestants, only Catholics, both or neither).

About a quarter of the general public (23%) correctly answered that only Protestants traditionally teach that salvation comes through faith alone. A plurality of U.S. adults (45%) said both Protestants and Catholics believe in sola fide, and one-in-ten said only Catholics hold this belief (11%). About one-in-five said neither Protestants nor Catholics believe this (19%).

Four-in-ten white evangelical Protestants (42%) answered this question correctly, but fewer white mainline Protestants (14%), black Protestants (14%) and Catholics (17%) did so.11 In fact, about half of Catholics incorrectly said that Catholicism traditionally teaches that salvation comes through faith alone (including 13% who said only Catholicism teaches this, and 41% who said both Catholicism and Protestantism do). Atheists and agnostics were more likely than members of several Christian subgroups to correctly answer the question.

College graduates did somewhat better on this question than those without a college degree, but still, just a third of college-educated adults correctly said that only Protestants teach sola fide.

Analysis of the data shows that for Protestants, knowing that only Protestantism traditionally teaches that salvation comes through faith alone is closely linked with believing that salvation comes through faith alone. Among Protestants who know that only Protestantism traditionally teaches that salvation comes through faith alone, about three-quarters (77%) embrace the concept of sola fide. But among the much larger share of Protestants who are not aware that sola fide is solely a Protestant teaching, far fewer (35%) believe that faith is all that is needed to get into heaven.

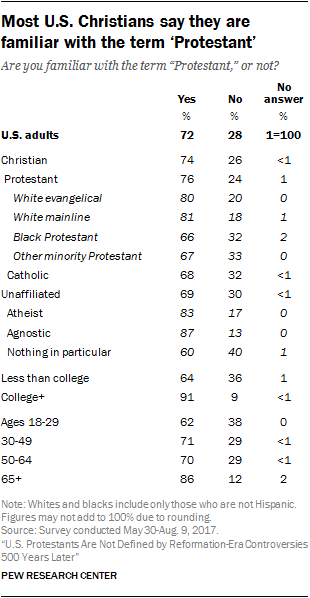

The survey asked respondents whether they are familiar with the term “Protestant,” and seven-in-ten U.S. adults said they are (72%). Three-quarters of Protestants (76%) say they are aware of the term, while slightly smaller shares of religiously unaffiliated adults (69%) and Catholics say the same (67%).12

The survey asked respondents whether they are familiar with the term “Protestant,” and seven-in-ten U.S. adults said they are (72%). Three-quarters of Protestants (76%) say they are aware of the term, while slightly smaller shares of religiously unaffiliated adults (69%) and Catholics say the same (67%).12

Among Protestants, roughly eight-in-ten white mainline (81%) and white evangelical Protestants (80%) say they are familiar with this term, while two-thirds of black Protestants say the same.13 And among religious “nones,” atheists and agnostics are more likely than those who say their religion is “nothing in particular” to be familiar with the term “Protestant.”

Nine-in-ten college graduates say they know the word “Protestant,” compared with 64% of those who have not received a college degree.

Age also is related to familiarity with the term “Protestant.” Adults ages 65 and older are much more likely than younger adults to say they are familiar with the word.

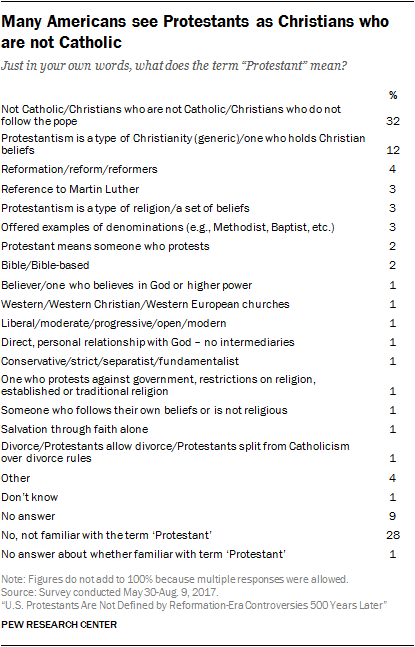

Respondents who said they are familiar with the term “Protestant” were asked to describe, in their own words, what the term means. The most common responses defined Protestant as Christians who are not Catholics or who don’t follow the pope (32%). For example, one respondent said Protestant means, “to belong to a religion that broke away from the Roman Catholic Church in ‘protest,’ or to object.” Another said Protestant referred to “those who protested against the perceived abuses by the pope and the Roman Catholic Church. Today, non-Catholic Christian denominations.”

Respondents who said they are familiar with the term “Protestant” were asked to describe, in their own words, what the term means. The most common responses defined Protestant as Christians who are not Catholics or who don’t follow the pope (32%). For example, one respondent said Protestant means, “to belong to a religion that broke away from the Roman Catholic Church in ‘protest,’ or to object.” Another said Protestant referred to “those who protested against the perceived abuses by the pope and the Roman Catholic Church. Today, non-Catholic Christian denominations.”

One-in-ten respondents said Protestantism is a type of Christianity or someone who holds Christian beliefs. Others used the word “reform” or “Reformation” to define Protestant (4%), and still others referenced Martin Luther, said Protestantism is a type of religion or set of beliefs, or offered examples of some Protestant denominations (3% each).

Most in U.S. say Catholics and Protestants today are religiously more similar than different

Six-in-ten U.S. adults (61%), including 57% of Protestants and 65% of Catholics, say that when they think about Catholics and Protestants today, they consider the two groups more similar than different, religiously. On the other hand, about a third of U.S. adults (36%), including 41% of Protestants and 32% of Catholics, say Catholics and Protestants today are more different than they are similar.

Six-in-ten U.S. adults (61%), including 57% of Protestants and 65% of Catholics, say that when they think about Catholics and Protestants today, they consider the two groups more similar than different, religiously. On the other hand, about a third of U.S. adults (36%), including 41% of Protestants and 32% of Catholics, say Catholics and Protestants today are more different than they are similar.

Depending on their response to this question, respondents received a follow-up question asking them to describe, in their own words, the most important way in which the two traditions are similar or different.

Depending on their response to this question, respondents received a follow-up question asking them to describe, in their own words, the most important way in which the two traditions are similar or different.

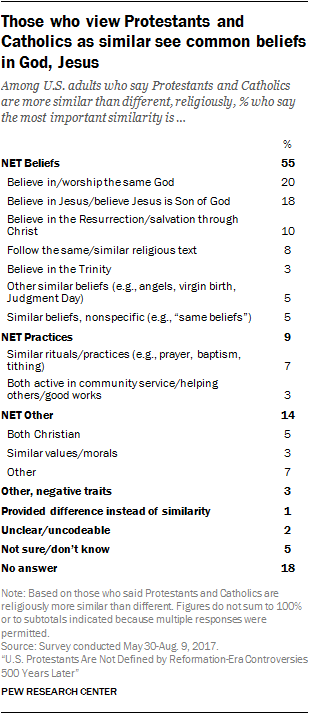

Among U.S. adults who said Protestantism and Catholicism are more similar than different, 55% cited shared beliefs as the key similarity. This includes 20% who said the two traditions believe in or worship the same God, and 18% who said both groups believe in Jesus Christ, or believe that he is the Son of God.

One-in-ten said Protestants and Catholics share common practices, such as being active in the community and helping others (3%). And 14% gave a variety of other, positive ways in which the two groups are similar, such as that “they both teach good morals and ethics” or that they are similar “in their mutual tolerance for the other’s approach to faith and justification.”

Americans who said Protestants and Catholics are more different than similar, religiously, were asked to describe the most important difference between the two groups. Within this category, the most common type of response was that beliefs are the most important distinction between Catholics and Protestants. This includes 9% who said the most important difference between the two groups is how they view Mary and the saints and 7% who said the key distinction is that Catholics follow the pope. According to one respondent, “Catholics pay heed and much respect to the pope, whereas Protestants are not directly influenced by his statements and ideas.”

Americans who said Protestants and Catholics are more different than similar, religiously, were asked to describe the most important difference between the two groups. Within this category, the most common type of response was that beliefs are the most important distinction between Catholics and Protestants. This includes 9% who said the most important difference between the two groups is how they view Mary and the saints and 7% who said the key distinction is that Catholics follow the pope. According to one respondent, “Catholics pay heed and much respect to the pope, whereas Protestants are not directly influenced by his statements and ideas.”

Some respondents also cited certain practices – such as prayer and confession – as ways in which Protestants and Catholics differ (11%). And still others noted the differences on a variety of social and political issues (5%). Additional responses highlighted perceptions of rules and strictness across the two faiths. One respondent wrote, “Catholics tend to be a more open-minded denomination,” while another said, “Protestants are more open to letting you live your [life].”

In addition to asking respondents whether Catholics and Protestants, in general, are mostly similar to or different from each other, the survey also asked respondents whether they view each of a series of religions as similar to or different from their own religion. On this latter question, Protestants and Catholics are split about whether the other Christian tradition is similar to their own faith. Half of Protestants (50%) say they think the Catholic religion is “very similar” or “somewhat similar” to their own religion, while the other half (49%) say Catholicism is “very different” or “somewhat different” from their own faith. Among Catholics, 54% say they think the Protestant religion is very similar or somewhat similar to their own religion, while 42% say Protestantism is very or somewhat different from their own faith.

Although Catholics and Protestants are divided as to how much the other faith resembles their own, members of each group are far more likely to say the other is similar to their own faith than they are to say any other religion is similar to their own. For example, while half of Protestants say Catholicism is similar to their own religion, just 32% say the same about Judaism, 19% say this about Mormonism, and about one-in-ten say this about Islam (12%), Buddhism (9%) or Hinduism (8%). Among Catholics, 41% say Judaism is similar to their own religion, while fewer say this about Mormonism, Islam, Buddhism or Hinduism.