Government restrictions by region

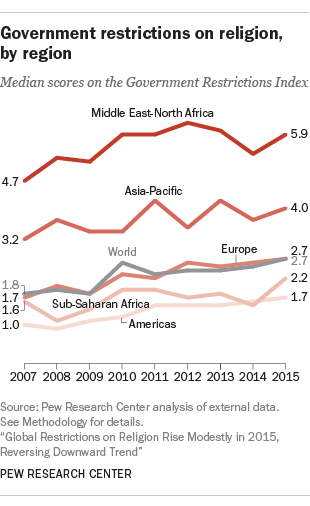

The median level of government restrictions on religion increased in four of the five regions analyzed in this report (Asia and the Pacific, the Middle East and North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa, and Europe) from 2014 to 2015 and remained roughly the same in one region (the Americas). The largest increase occurred in sub-Saharan Africa.

The median level of government restrictions on religion increased in four of the five regions analyzed in this report (Asia and the Pacific, the Middle East and North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa, and Europe) from 2014 to 2015 and remained roughly the same in one region (the Americas). The largest increase occurred in sub-Saharan Africa.

Continuing the trend from previous years, the Middle East-North Africa region had the highest median level of government restrictions in 2015. The median score for the 20 countries in the region increased to 5.9 in 2015, up from 5.4 the previous year, and was more than double the global median (2.7). These countries exhibited many of the same government restrictions as previous years, but experienced increases in some measures. For example, the number of governments that harassed religious groups rose from 14 to 17 countries, and the number that displayed hostility involving physical violence toward minority or nonapproved religious groups increased from eight to 11.

In the Asia-Pacific region, the median score on the Government Restrictions Index increased from 3.7 in 2014 to 4.0 in 2015, following a decrease during the previous year. Half (25) of the region’s 50 countries had increases in government restrictions in 2015. In Nepal, for instance, a government-funded organization prevented the burial of Christians in a cemetery behind a Hindu temple, despite allowing the burial of other non-Hindu indigenous faiths.30

Europe’s median score increased slightly from 2.6 to 2.7, with an increase in government restrictions in 31 of 45 countries. Among the main reasons behind the increase were upticks in government harassment and intimidation of religious groups and the use of government force against religious groups (see the Overview of this report for more details).

Sub-Saharan Africa’s median increase from 1.5 in 2014 to 2.2 in 2015 was caused in part by increases in government harassment of religious groups or individuals and government hostility toward minority or nonapproved religious groups. For more details on the increase in government restrictions in this region, see the sidebar in Chapter 3.

In the Americas, the median score for government restrictions remained roughly the same from 2014 (1.6) to 2015 (1.7).31 As in previous years, the Americas’ median score remained significantly lower than the global median (2.7).

Social hostilities by region

The median level of social hostilities involving religion decreased from 2014 to 2015 in the Middle East-North Africa region, increased in two regions (sub-Saharan Africa and Europe), and remained relatively unchanged in the Americas and Asia-Pacific regions. The global median score increased from 1.5 to 2.0.

The median level of social hostilities involving religion decreased from 2014 to 2015 in the Middle East-North Africa region, increased in two regions (sub-Saharan Africa and Europe), and remained relatively unchanged in the Americas and Asia-Pacific regions. The global median score increased from 1.5 to 2.0.

Despite decreasing from 6.0 in 2014 to 5.3 in 2015, the median level of social hostilities in the Middle East-North Africa region continued to be the highest of any region and remained well above the global median. Across the region’s 20 countries, six had increases in social hostilities while 13 had decreases (and one country, Oman, had no change in its Social Hostility Index score from 2014 to 2015). A decline in social hostilities in Israel reflected in part the ceasing of the religion-related armed conflict between Israel and Palestinians in the Gaza Strip that dominated the summer of 2014.32

By contrast, social hostilities involving religion increased in sub-Saharan Africa, rising from a median score of 1.0 in 2014 to 1.7 in 2015. Some of this was due to a rise in the use of violence or the threat of violence to enforce religious norms, which increased in 16 of the region’s 48 countries. For more details on the increase in social hostilities in this region, see sidebar in Chapter 3.

Europe also experienced an increase in its median score, from 1.9 to 2.1 in 2015. Some of this was due to a rise in mob violence related to religion, with 17 countries experiencing this (up from nine the previous year). Similarly, individuals in Europe were assaulted or displaced from their homes in retaliation for religious activities considered offensive or threatening to the majority faith (including preaching and other forms of religious expression) in 28 countries in 2015 – a significant increase from nine countries in 2014. In Austria, for instance, a man wearing a Star of David necklace was assaulted at a shopping mall, where his attackers shouted anti-Semitic slurs before beating him.33 And in Ireland, a Saudi woman who was riding a bus was punched by a man who said he hated Islam.34

Sidebar: Rising restrictions and hostilities in sub-Saharan Africa

The Nigeria-based extremist group Boko Haram, following its 2014 abduction of hundreds of schoolgirls in northeastern Nigeria, crossed international borders for numerous attacks in 2015.35 In February 2015, for example, Boko Haram attacked Fotokol in Cameroon and Bosso and Diffa in Niger – all along the Nigerian border – killing at least 71 people.36 And in the summer of 2015, Boko Haram fighters targeted villages and cities in Niger and Chad, killing at least 38 people in Niger and 49 people in two separate attacks in Chad.37 In one of the Chad attacks, a suicide bomber wore a burqa as a disguise.38

Not only did these incidents contribute to an increase in the median level of social hostilities involving religion in sub-Saharan Africa in 2015, but also government policies and actions in response to the Boko Haram threat caused a rise in the median level of government restrictions. Compared with other regions, sub-Saharan Africa experienced the largest increases in both government restrictions and social hostilities involving religion in 2015.

Several governments indicated that Boko Haram’s attacks during the year led them to impose restrictions on religion, including bans on varied forms of Islamic veils for women and harassment of Muslim women wearing veils. For example, a gendarme officer in Cameroon reportedly tried to forcibly remove a Muslim woman’s headscarf at a highway roadblock in the region of Bamenda, while a Catholic nun with a head covering was allowed to pass through unchallenged.39

In addition to bans on Islamic veils in Cameroon and Niger (noted in the Overview of this report), Chad and the Republic of Congo enacted similar restrictions in response to terror attacks. In Chad, the government cited the risk of concealing explosives under a burqa; 62 Chadian women were arrested for wearing burqas in 2015.40 And the Republic of Congo banned the full-face Islamic veil in public places as a reaction to security concerns, despite a lack of extremist violence in the country.41

There also were incidents of harassment elsewhere. For instance, Muslim students in Ghana reported that officials ordered girls to remove their hijabs before taking the West African Senior School Certificate Examination.42

Government restrictions on religion in the region were not limited to regulating religious dress. In Cameroon, 84 children remained in custody without charges for most of 2015, following raids the previous year on Quranic schools suspected of recruiting children for Boko Haram.43 And some restrictions were unrelated to the Boko Haram threat entirely: In Rwanda, several Jehovah’s Witnesses were dismissed from government jobs for refusing to touch the national flag while taking the public servants’ oath.44 (Jehovah’s Witnesses are taught to avoid saluting national flags.)

These types of incidents contributed to sub-Saharan Africa’s median Government Restrictions Index (GRI) score rising from 1.5 in 2014 to 2.2 in 2015 – the largest increase of any region. Cameroon, Comoros and Niger experienced especially large increases (2.0 points or more) in their GRI scores.

These types of incidents contributed to sub-Saharan Africa’s median Government Restrictions Index (GRI) score rising from 1.5 in 2014 to 2.2 in 2015 – the largest increase of any region. Cameroon, Comoros and Niger experienced especially large increases (2.0 points or more) in their GRI scores.

Sub-Saharan Africa experienced the largest increase in the median level of social hostilities involving religion in 2015. Six of the 48 countries in the region saw surges of at least 2.0 points in their level of social hostilities: Niger had the largest increase, followed by Chad, South Sudan, Burkina Faso, the Republic of the Congo and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Most notably, the use of violence or the threat of violence to enforce religious norms rose in 16 countries. This type of hostility involves forcing others to submit to a particular religious point of view.

People accused of practicing witchcraft were targeted in a number of cases. In the Republic of Congo, two elderly men were killed after being accused of witchcraft.45 And in Burkina Faso, elderly women were often accused of witchcraft and barred from their villages. A Roman Catholic Church-operated organization in the capital, Ouagadougou, supported 260 women accused of witchcraft in 2015, and another government center sheltered 84 women.46 During the year, people accused of witchcraft also were targeted in the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ghana, Tanzania and Zambia.

Meanwhile, people practicing witchcraft rituals targeted individuals with albinism. In Malawi, there was an increase in the demand for body parts of people with albinism; the Association of People Living with Albinism in Malawi reported 19 cases of abuse, including eight deaths, in 2015.47 In Tanzania, one child with albinism was killed, and three other cases were reported involving “abduction, mutilation and dismemberment of bodies.”48