Introduction

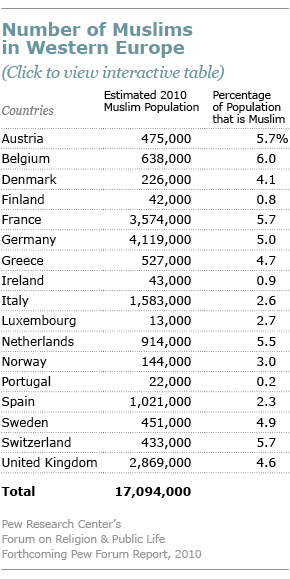

Over the past two decades, the number of Muslims living in Western Europe has steadily grown, rising from less than 10 million in 1990 to approximately 17 million in 2010.1 The continuing growth in Europe’s Muslim population is raising a host of political and social questions. Tensions have arisen over such issues as the place of religion in European societies, the role of women, the obligations and rights of immigrants, and support for terrorism. These controversies are complicated by the ties that some European Muslims have to religious networks and movements outside of Europe. Fairly or unfairly, these groups are often accused of dissuading Muslims from integrating into European society and, in some cases, of supporting radicalism.

To help provide a better understanding of how such movements and networks seek to influence the views and daily lives of Muslims in Western Europe, the Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life has produced profiles of some of the oldest, largest and most influential groups – from the Muslim Brotherhood to mystical Sufi orders and networks of religious scholars. The selected groups represent the diverse histories, missions and organizational structures found among Muslim organizations in Western Europe. Certain groups are more visible in some European countries than in others, but all of the organizations profiled in the report have global followings and influence across Europe.

The profiles provide a basic history of the groups’ origins and purposes. They examine the groups’ religious and political agendas, as well as their views on topics such as religious law, religious education and the assimilation of Muslims into European society. The profiles also look at how European governments are interacting with these groups and at the relationships between the groups themselves. Finally, the report discusses how the movements and networks may fare in the future, paying special attention to generational shifts in the groups’ leadership and membership ranks as well as their use of the Web and other new media platforms in communicating their messages.

It is important to note that the report does not attempt to cover the full spectrum of Muslim groups in Western Europe. For instance, it does not include profiles of the many Muslim organizations that have been founded in Western Europe in recent decades, including local social service providers, or the governing councils of major European mosques. Rather, the primary focus of the report is on transnational networks and movements whose origins lie in the Muslim world but that now have an established presence in Europe. Influential Islamic schools of thought, such as Salafism or Deobandism, are discussed in terms of their influence on various Muslim groups and movements rather than in separate profiles.2

Perceptions About Links to Terrorism

Muslims have been present in Western Europe in large numbers since the 1960s, when immigrants from Muslim-majority areas such as North Africa, Turkey and South Asia began arriving in Britain, France, Germany and other European nations, often to take low-wage jobs.3 Many of the major Muslim networks and movements operating in Western Europe today originated in Muslim-majority countries, including Egypt, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and Turkey.

The overseas origins of the groups, and their continuing ties to affiliates abroad, have prompted concerns that by strengthening Muslims’ connections to the umma – the world community of Muslim believers – they may be encouraging Muslims to segregate themselves from the rest of European society.4 In addition, some in the West perceive many Muslim groups as fomenters of radical Islam and, ultimately, terrorism.

It is difficult to generalize about Muslim groups in Western Europe because they vary so widely in their philosophies and purposes. Certain groups, including radical Islamist movements, do work to foster extremist sentiments or to detach Muslims from the European societies in which they live. But other groups focus on different goals, such as helping Muslim communities deal with day-to-day religious issues, improving schools or encouraging personal piety.

The profiles in this report provide a sense of whether the core philosophy and goals of each group tend to tilt toward or away from Islamic radicalism or extremism, as well as the extent to which they encourage Muslims to integrate into European society, participate in local and national politics and cooperate with non-Muslims on social and political matters. Whenever possible, the report notes instances where questions have been raised in the press, scholarly journals or government sources about a group’s possible terrorist links or connections. But the report does not attempt to answer the question of whether particular groups and movements are directly or indirectly tied to terrorism. For one thing, it is often impossible to tell. While individuals with violent or radical inclinations may participate in a particular group’s activities, the group itself may or may not do anything to foster violence or extremism.

Furthermore, many European Muslims see these movements and networks as generically “Islamic” and may not care about or even be aware of their political ideologies and social agendas. Individuals also may support or participate in some of a group’s activities but not others. For instance, individuals attending a religious class sponsored by an organization with ties to the Muslim Brotherhood may not necessarily support the group’s broader political agenda. Some studies have shown that exclusive affiliation with a single group or movement is rare, especially among younger Muslims.5 Rather, European Muslims often participate in the activities of multiple groups, sometimes simultaneously.

Likewise, some people are drawn to particular groups principally because of their ethnic or regional origins rather than their social or political viewpoints. For example, the movement known as Jama’at-i Islami appeals primarily to South Asian Muslims, while the Muslim Brotherhood appeals primarily to those of Arab descent. However, there are signs that the ethnic character of some groups and movements is becoming less pronounced, at least among younger generations of Muslims.6

Small Membership, Large Influence

Although many Muslims in Western Europe participate in the activities of these movements and networks, the groups’ formal membership rolls appear to be relatively small. Indeed, some studies suggest that relatively few Muslims in Europe belong to any religious organization in any formal sense, including mosques.7

Despite their relatively low levels of formal membership, Muslim movements and networks often exert significant influence by setting agendas and shaping debates within Muslim communities in Western Europe. Whether or not they reflect the views of most Muslims in a community, they often are instrumental in determining which concerns receive attention as “Muslim issues” in the media, in government circles and in the broader public debate about Islam in Europe.

In addition, many Islamic groups now serve as interlocutors between Muslims and the governments of the European countries in which they live. This arrangement has often come about at the behest of government officials looking for organizations that can serve as conduits to their Muslim constituents. A number of European governments have established councils in recent years to reach out to their Muslim populations. For instance, in 2003, the French government partnered with a number of large Muslim groups to establish the Conseil Français du Culte Musulman (French Council of the Muslim Faith), which now serves as an official representative body for the country’s Muslims in dealing with the government in much the same way that certain Catholic and Jewish organizations in France serve as official points of contact for their respective communities.

Pursuing Their Agendas

The growing connections between Islamic groups and European governments, as well as the integration of some of these groups into the continent’s political mainstream, have not led to a decrease in activism on the part of these groups. If anything, Muslim groups and movements have become more visible on the European political stage and are becoming more adept at using national media and political channels to pursue a wide range of agendas. For example, the Muslim Association of Britain, an affiliate of the Muslim Brotherhood, became a major player in Britain’s anti-Iraq War movement by partnering with disaffected members of the British Labor Party and the Stop the War Alliance.

Even groups that advocate for Muslim political causes often do so by working within, rather than outside of, Europe’s legal and political institutions. Most of the movements – including the politicized ones, such as the Muslim Brotherhood – encourage their followers to participate in local and national European elections. The Muslim Association of Britain, for example, routinely publishes lists of candidates – both Muslims and non-Muslims – that have been endorsed by the group.

Many Muslim movements have embraced the tools afforded by new media, including websites, Twitter, blogs, online videos and social networking sites, to reach new followers. Web destinations such as Facebook and YouTube are replete with content from Muslim groups spanning the ideological spectrum. The groups’ messages – sometimes coming in the form of hip-hop music, graphic novels, sports programs and other popular-culture formats – are designed to appeal to young Muslims raised in Western Europe.

Radical groups such as al-Qaeda have used websites to propagate the views of jihadi scholars and, according to some analysts, to recruit potential activists. 8 But groups that focus on promoting personal devotion, such as the Tablighi Jama’at and traditional Sufi orders, also have used the Web to promote themselves, uploading videos of their conferences and creating Facebook pages dedicated to their key leaders.9

While the internet has made it easier for groups to share their messages, it also has raised new challenges. Because of the prevalence of new media outlets, individual Muslims are able to receive information from a variety of religious groups, which potentially dilutes the message and influence of any single group.

At the same time, the internet and other new technologies have allowed Islamic groups in Europe to reach Muslims worldwide. Some European-based groups are now exporting ideas, methods and money back to Muslim-majority countries in the Middle East, South Asia and elsewhere. European affiliates of the Muslim Brotherhood, for example, are engaged in ongoing discussions with intellectuals and ideologues in the Middle East about participation in democratic politics. And radical groups such as Hizb ut-Tahrir, whose global headquarters are in the Middle East, rely on their European branches for publicity and fundraising.

Partly in reaction to the growth and visibility of Muslim movements in Western Europe, Christian and Jewish organizations in the region also have attracted more public attention in recent years and taken on renewed relevance in the eyes of some Europeans. 10 In that sense, Muslim groups, collectively, may be helping to create more space for religion in general in the European public square.