Throughout this report we utilize a scale composed of 10 questions asked on Pew Research Center surveys going back to 1994 to gauge peoples’ ideological worldview. The questions cover a range of political values including attitudes about size and scope of government, the social safety net, immigration, homosexuality, business, the environment, foreign policy and racial discrimination. The individual items are discussed at the end of this section, and full details about the scale are in Appendix A.

The scale is designed to measure how consistently liberal or conservative people’s responses are across these various dimensions of political thinking (what some refer to as ideological ‘constraint’). Other sections of the report look at people’s levels of partisanship, engagement and policy views. Where people fall on this scale does not always align with whether they think of themselves as liberal, moderate or conservative. See the discussion at the end of this section for this analysis.

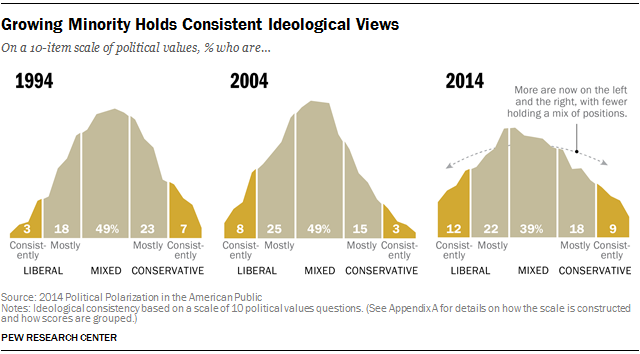

To be sure, those with across-the-board liberal or conservative views remain in the minority; most Americans continue to express at least some mix of liberal and conservative attitudes. Yet those who express ideologically consistent views have disproportionate influence on the political process: They are more likely than those with mixed views to vote regularly and far more likely to donate to political campaigns and contact elected officials.

Moreover, consistent liberals and conservatives approach the give-and-take of politics very differently than do those with mixed ideological views. Ideologically consistent Americans generally believe the other side – not their own – should do the giving. Those in the middle, by contrast, think both sides should give ground.

Throughout most of this report, Republicans and Democrats include independents who lean toward the parties. In virtually all situations, these Republican and Democratic leaners have far more in common with their partisan counterparts than they do with each other if combined into a single “independent” group. See Appendix B for more detail.

As Partisans Move Further Apart, the Middle Shrinks

In 2012, the Pew Research Center updated its 25-year study of the public’s political values, finding that the partisan gap in opinions on more than 40 separate political values had nearly doubled over the previous quarter century. The new study investigates whether there is greater ideological consistency than in the past; that is, whether more people now have straight-line liberal or conservative attitudes across a range of issues, from homosexuality and immigration to foreign policy, the environment, economic policy and the role of government.

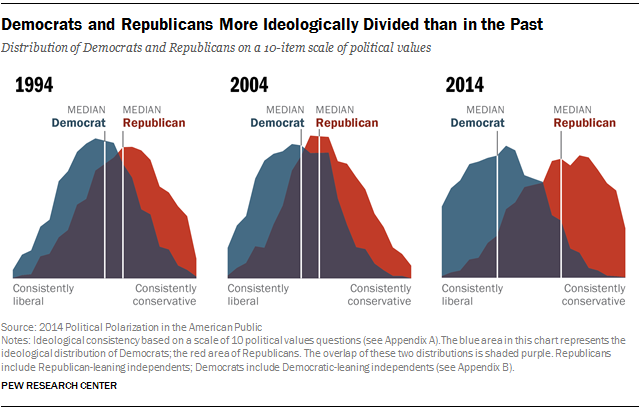

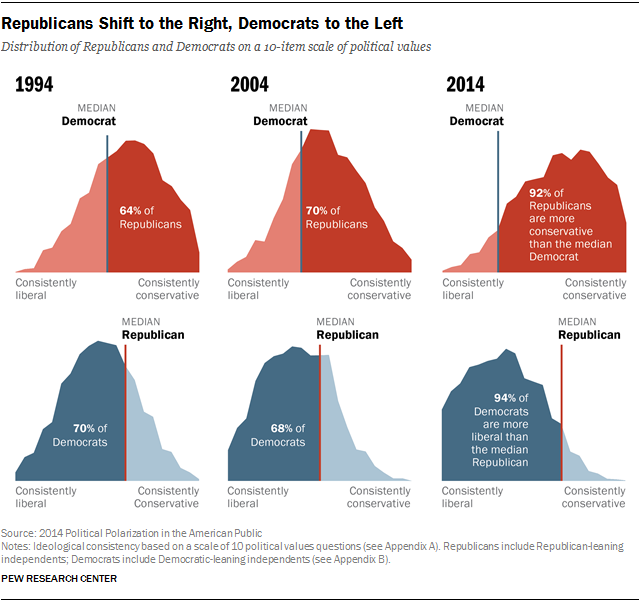

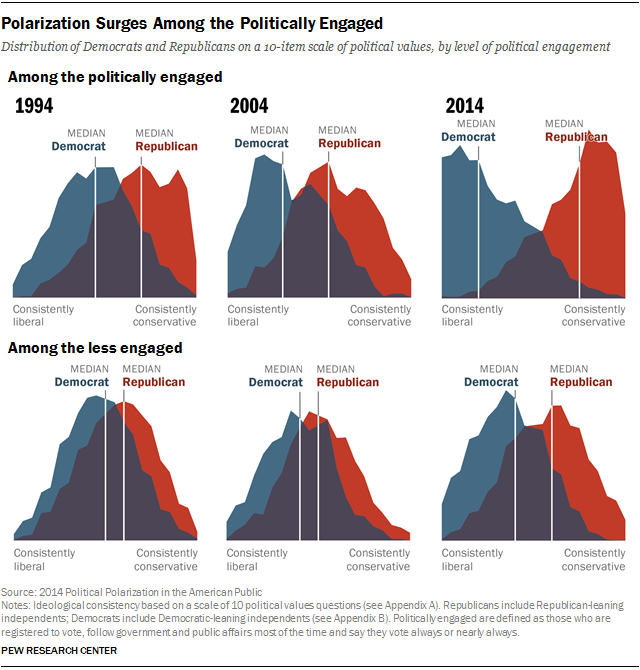

The graphic below shows the extent to which members of both parties have become more ideologically consistent and, as a result, further from one another. When responses to 10 questions are scaled together to create a measure of ideological consistency, the median (middle) Republican is now more conservative than nearly all Democrats (94%), and the median Democrat is more liberal than 92% of Republicans.

In 1994, the overlap was much greater than it is today. Twenty years ago, the median Democrat was to the left of 64% of Republicans, while the median Republican was to the right of 70% of Democrats. Put differently, in 1994 23% of Republicans were more liberal than the median Democrat; while 17% of Democrats were more conservative than the median Republican. Today, those numbers are just 4% and 5%, respectively.

As partisans have moved to the left and the right, the share of Americans with mixed views has declined. Across the 10 ideological values questions in the scale, 39% of Americans currently take a roughly equal number of liberal and conservative positions. That is down from nearly half (49%) of the public in surveys conducted in 1994 and 2004. As noted, the proportion of Americans who are now more uniformly ideological has doubled over the last decade: About one-in-five Americans (21%) are now either consistently liberal (12%) or consistently conservative (9%) in their political values, up from just one-in-ten in 2004 (11%) and 1994 (10%).

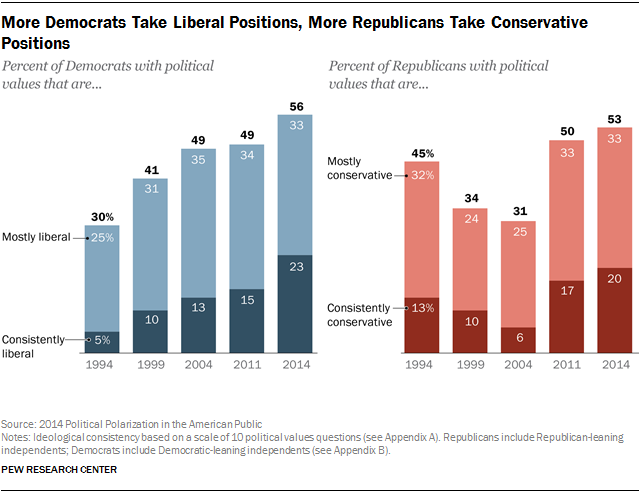

This translates into a growing number of Republicans and Democrats who are on completely opposite sides of the ideological spectrum, making it harder to find common ground in policy debates. The share of Democrats who hold consistently liberal positions has quadrupled over the course of the last 20 years, growing from just 5% in 1994 to 13% in 2004 to 23% today. And more Republicans are consistently conservative than in the past (20% today, up from 6% in 2004 and 13% in 1994), even as the country as a whole has shifted slightly to the left on the 10 item scale.

Being ideologically consistent does not equate to being politically “extreme” — an important distinction in understanding polarization. This is one reason why we avoid using the term “ideologue” to describe those on the tails of the ideological consistency scale.

Another section of this report explores the relationship between being ideologically consistent and holding positions on the periphery of current policy debates—finding evidence that those who are ideologically mixed are often as likely to hold more “extreme” positions as those who are more ideologically consistent. Conversely, one can be uniformly liberal (or conservative) in one’s political values, but have a “moderate” approach to issues.

Is Polarization Asymmetrical?

The ideological consolidation nationwide has happened on both the left and the right of the political spectrum, but the long-term shift among Democrats stands out as particularly noteworthy. The share of Democrats who are liberal on all or most value dimensions has nearly doubled from just 30% in 1994 to 56% today. The share who are consistently liberal has quadrupled from just 5% to 23% over the past 20 years.

The share of Democrats who are liberal on all or most value dimensions has nearly doubled from just 30% in 1994 to 56% today

In absolute terms, the ideological shift among Republicans has been more modest, in 1994, 45% of Republicans were right-of-center, with 13% consistently conservative. Those figures are up to 53% and 20% today.

But there are two key considerations to keep in mind before concluding that the liberals are driving ideological polarization. First, 1994 was a relative high point in conservative political thinking among Republicans. In fact, between 1994 and 2004 the average Republican moved substantially toward the center ideologically, as concern about the deficit, government waste and abuses of social safety net that characterized the “Contract with America” era faded in the first term of the Bush administration.

The GOP ideological shift over the past decade has matched, if not exceeded, the rate at which Democrats have become more liberal

But since 2004, Republicans have veered sharply back to the right on all of these dimensions, and the GOP ideological shift over the past decade has matched, if not exceeded, the rate at which Democrats have become more liberal.

A second consideration is that the nation as a whole has moved slightly to the left over the past 20 years, mostly because of a broad societal shift toward acceptance of homosexuality and more positive views of immigrants. Twenty years ago, these two issues created significant cleavages within the Democratic Party, as many otherwise liberal Democrats expressed more conservative values in these realms. But today, as divisions over these issues have diminished on the left, they have emerged on the right, with a subset of otherwise conservative Republicans expressing more liberal values on these social issues.

However, on economic issues and the role of government, Republicans and Democrats are both substantially more consolidated than in the past: 37% of Republicans are consistently conservative and 36% of Democrats are consistently liberal on a five-item subset of the scale restricted to just the items about economic policy and the size of government. In 1994, those proportions were 23% and 21%, respectively.

Political Engagement Increasingly Linked to Polarization

In today’s political environment, party (and partisan leaning) predicts ideological consistency more than ever before, and this is particularly the case among the politically attentive. Among Americans who keep up with politics and government and who regularly vote, fully 99% of Republicans are now more conservative than the median Democrat, while 98% of Democrats are more liberal than the median Republican. While engaged partisans have always been ideologically divided, there was more overlap in the recent past; just 10 years ago these numbers were 88% and 84%, respectively.

Participation in politics is one of the key correlates of polarization, and is measured in greater detail in a separate section of this report. Because the analysis here is making comparisons over time, we are limited to using three questions that were asked consistently in Pew Research surveys since 1994. To be classified as “highly engaged,” a respondent must say they are registered to vote, always or nearly always vote, and follow what is going on in government and public affairs most of the time. In each year of the study, this represents roughly a third of the public, while the other two-thirds are classified as “less engaged.”

The 2014 survey goes into far greater detail on various forms of political participation and engagement, with more detail here.

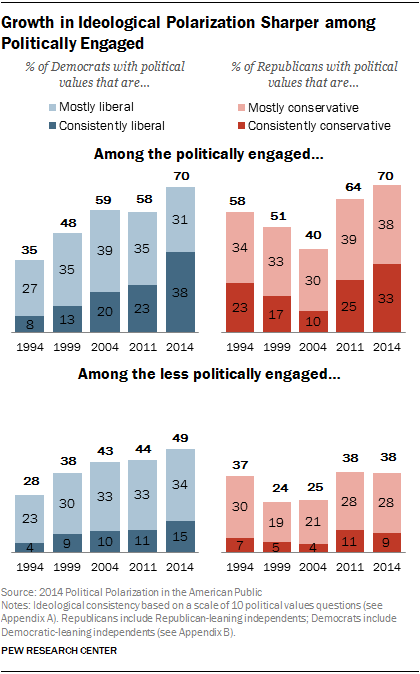

Today, almost four-in-ten (38%) politically engaged Democrats are consistent liberals, up from only 8% in 1994 and 20% in 2004. And the rise is also evident on the right: 33% of politically engaged Republicans are consistent conservatives, up from 23% in 1994, and just 10% in 2004.

Today, almost four-in-ten (38%) politically engaged Democrats are consistent liberals, up from only 8% in 1994 and 20% in 2004. And the rise is also evident on the right: 33% of politically engaged Republicans are consistent conservatives, up from 23% in 1994, and just 10% in 2004.

Within both parties, 70% of the politically engaged now take positions that are mostly or consistently in line with the ideological bent of their party. By comparison, the equivalent positions were held by 58% of Republicans and 35% of Democrats in 1994 and 40% of Republicans and 59% of Democrats in 2004.

Engaged citizens have always tended to be more ideologically oriented, but the correlation has increased in recent years, particularly among Democrats. Today, 70% of highly engaged Democrats are mostly or consistently liberal in their views, compared with about half (49%) of less engaged Democrats (the other half are either ideologically mixed or conservative). Twenty years ago, there was far less of an engagement gap in ideological thinking, as 35% of highly engaged and 28% of less engaged Democrats were left of center.

The shift in ideology among Republicans is more complex. Between 1994 and 2004 Republicans actually became less ideologically oriented, as support for government programs and more positive views about the effectiveness of government grew during George W. Bush’s first term. But over the past decade, the GOP has moved solidly to the right – particularly those who are more politically engaged. Today, 70% of highly engaged Republicans are either consistently or mostly conservative, up from 40% in 2004. By comparison, just 38% of less engaged Republicans are right of center (the majority offer a mix of liberal and conservative views).

Polarization among Elected Officials

This movement among the public, and particularly the engaged public, tracks with increasingly polarized voting patterns in Congress, though to a far lesser extent. As many congressional scholars have documented, Republicans and Democrats on Capitol Hill are now further apart from one another than at any point in modern history, and that rising polarization among elected officials is asymmetrical, with much of the widening gap between the two parties attributable to a rightward shift among Republicans. As a result, using a widely accepted metric of ideological positioning, there is now no overlap between the two parties; in the last full session of Congress (the 112th Congress, which ran from 2011-12), every Republican senator and representative was more conservative than the most conservative Democrat (or, putting it another way, every Democrat was more liberal than the most liberal Republican).

But this was not always the case. Forty years ago, in the 93rd Congress (1973-74), fully 240 representatives and 29 senators were in between the most liberal Republican and most conservative Democrat in their respective chambers. Twenty years ago (the 103rd Congress from 1993-94) had nine representatives and three senators in between the most liberal Republican and most conservative Democrat in their respective chambers. Today, there is no overlap. And while by this measure the pace of change may appear to have slowed in the past 20 years, the ideological distance between members of the two parties has continued to grow steadily over this period.

Growing Partisan Polarization Spans Domains

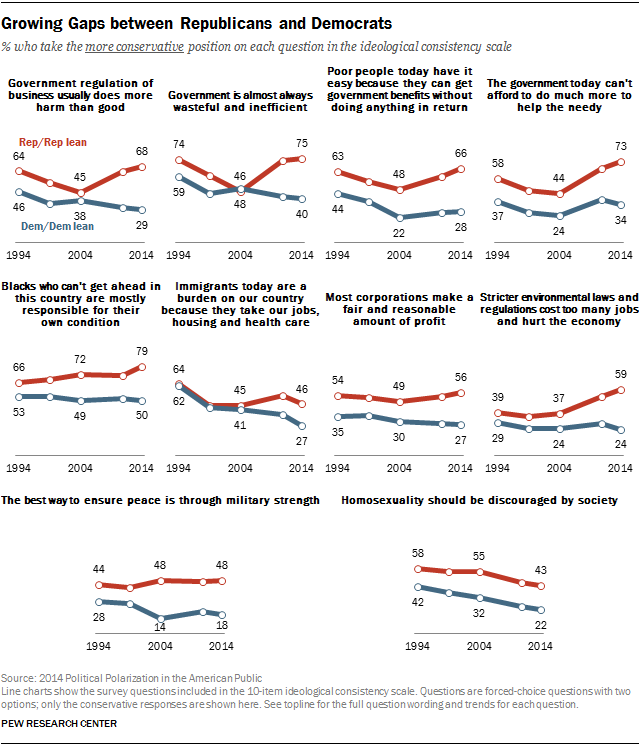

The growth in partisan polarization is evident across a range of political values, as nearly all of the traditional gaps between Republicans and Democrats have widened. The results of the current survey echo the findings in the 2012 values study.

The current survey tracks trends on a different set of questions going back to 1994, with parallel conclusions: Partisan divides have deepened across most core political domains, including on nearly every measure in the ideological consistency scale.

For instance, while Democrats have always been more supportive than Republicans of the social safety net, the partisan divide on these questions has increased substantially over the last 20 years. Two-thirds of Republicans (66%) believe that “poor people today have it easy because they can get government benefits without doing anything in return;” just 25% say “poor people have hard lives because government benefits don’t go far enough to help them live decently.” Among Democrats, just 28% believe the poor have it easy. The partisan gap on this measure is now 38 points, up from 19 points in 1994 and 26 points in .

Similarly, in 1994, there was a relatively narrow 10-point partisan gap in views on environmental regulation. Today, the gap is 35 points, as the proportion of Republicans who say that “stricter environmental laws and regulations cost too many jobs and hurt the economy” has grown from 39% in 1994 to 59%, while Democratic opinion has shifted slightly in the other direction.

And although immigration attitudes have shifted in a liberal direction among both Democrats and Republicans, a partisan gap has emerged where none was evident 20 years ago. In 1994, 64% of Republicans and 62% of Democrats viewed immigrants as a burden on the country; today 46% of Republicans but just 27% of Democrats say this.

For nine of the 10 items in the ideological consistency scale, the partisan gap has grown wider over the last 20 years. The sole exception is in views of homosexuality: Both Democrats and Republicans have become more liberal on this question over the years, as fewer now say that “homosexuality should be discouraged (rather than accepted) by society.” However, the current 21-point partisan gap on this question is only slightly wider than the 16 point gap in 1994.

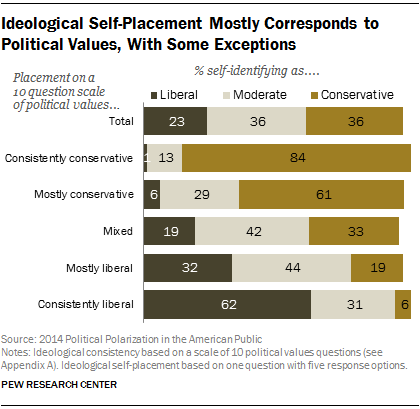

Ideological Self-Placement and Ideological Consistency

Where people fall on the scale of ideological consistency discussed throughout this report is strongly correlated with how people describe themselves. But for some, how they see their own ideology doesn’t align with their expressed political values.

In recent years, Americans have consistently been far more likely to self-identify as conservative than as liberal – by a 36% to 23% margin in the current survey.

In recent years, Americans have consistently been far more likely to self-identify as conservative than as liberal – by a 36% to 23% margin in the current survey.

Fully 84% of those who are consistently conservative in their ideological positions call themselves conservative, as does a smaller majority (61%) of those who are “mostly conservative” on the scale.

But those who express consistently or mostly liberal values, are less likely to embrace the “liberal” label. About six-in-ten (62%) consistent liberals say they are liberal, with 31% saying they are moderate, and a handful (6%) calling themselves conservative. And among those who are mostly liberal on the ideological consistency scale, more (44%) say they are moderate than say they are liberal (32%).

While the plurality (42%) of those who are ideologically mixed label themselves as moderate, the remainder are more likely to say they are conservative (33%) than liberal (19%).

Interactive

Interactive