Center researchers developed a plan to retire a subset of panelists who are overrepresented both demographically and politically. In raw, unadjusted numbers, the ATP contains proportionately too many college graduates, registered voters and Democratic-leaning adults. This is neither intentional nor unique to the ATP; instead it stems from such adults being more amenable to taking surveys and is a common challenge in modern polling. Each ATP survey is weighting to correct for these patterns.

The retirement strategy is built around two key metrics: how the unweighted vote preference on the ATP aligns with the 2020 election, and panelists’ frame weights. The retirement focuses on unweighted 2020 vote estimates on the ATP as opposed to weighted figures because the goal is to stop relying so heavily on weighting. A “frame weight” is a number assigned to each member of the ATP. It represents how much a panelist needs to get weighted up or weighted down to make the entire panel representative of all U.S. adults. Panelists who are overrepresented on the panel have low frame weight values (between 0 and 1). Panelists who are underrepresented have frame weight values greater than 1.

By retiring about 2,500 of our roughly 13,500 active panelists, we can align the unweighted ATP with the picture of the nation revealed by the 2020 election. The retirement strategy entails the following steps:

1. Identify panelists who are overrepresented based on their frame weight. Panelists with frame weight values 0.5 or less (i.e., people substantially overrepresented) were deemed eligible for retirement, while those with larger weight values were deemed ineligible.

2. Identify panelists without hard to reach characteristics. There are some specific subgroups that are underrepresented, extremely expensive to recruit, and important to data quality. It is not productive to retire such people. Researchers created a protective flag for panelists with any of the following characteristics: responds in Spanish, uses a Center-provided tablet, age 18-24, or has high school education level or less. Panelists with this protective flag were deemed ineligible for retirement.

3. Addressing the partisan balance. Researchers created a 2020 presidential vote preference variable for all panelists, including nonvoters. The data came from the 2020 post-election survey, which measured vote choice among voters and candidate preference among nonvoters. Based on their answers, panelists were categorized as:

- Voted/Preferred Trump

- Voted/Preferred Biden

- Voted/Preferred another candidate

- Noncitizen

- Refused question or did not respond to post-election survey

Researchers then used information associated with vote choice (party affiliation, race/ethnicity, education, age, gender and metro status) to impute vote/preference for panelists in the last category. Panelists in the first category were deemed ineligible for retirement.

4. Subsample from the retirement-eligible panelists.In total, about 3,800 panelists had a frame weight value of 0.5 or less and have none of the protected characteristics (Spanish language, tablet, age 18-24, high school or less, Trump supporter). These panelists were eligible for retirement. The next step was to subsample from them such that the entire panel aligns with the portrait of the country revealed by the election without relying on weighting. Researchers subsampled from the retirement-eligible panelists with probability proportional to the inverse of their frame weight. In other words, the most overrepresented panelists (those weighted down the most) were the most likely to be retired. For this process only, the frame weight was modified so that the panel aligns not just with demographics of the U.S. population but also with the vote outcome and voter turnout rate in the 2020 presidential election.

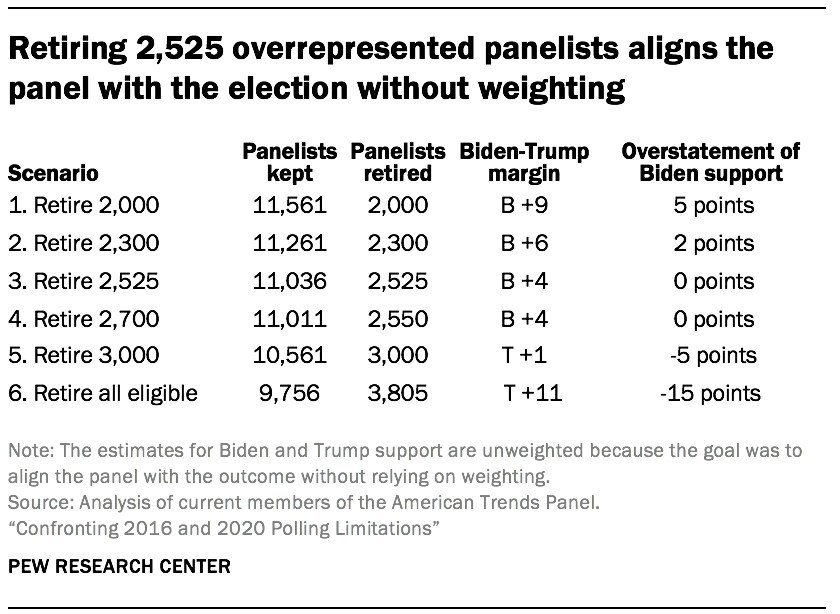

Researchers simulated subsampling varying fractions of those eligible for retirement. For each simulation, researchers computed the unweighted 2020 vote using post-election survey respondents who would not be retired under the simulation. The simulations are unweighted because the goal is to stop relying on weighting to fix these biases. The analysis indicated that retiring about 2,500 of the eligible panelists (scenario 3) would align the panel to the 2020 vote outcome of Biden receiving 51% of the vote and Trump receiving 47%. This is the scenario being implemented this year.

Fortunately, retiring those roughly 2,500 panelists does not meaningfully impair surveys conducted on the ATP. After the retirement, the panel will still have over 11,000 active panelists, which is more than enough for measuring U.S. public opinion.

This retirement strategy is not a perfect, permanent solution for ensuring a proper partisan balance on the ATP, but it is the most effective immediate step we can take to eliminate the imbalance that we currently rely on weighting to correct.

Implications for ATP estimates

Researchers used two recent surveys to examine the effects from implementing the retirement. This was done through simulation. Researchers removed the retired panelists from two survey datasets and then reweighted each survey using only the remaining respondents. Researchers compared these simulated post-retirement estimates to the pre-retirement estimates released from the surveys. Any differences in the estimates are attributable to the retirement strategy.

Overall, the effects from the retirement are subtle, slightly increasing estimates for some conservative attitudes. For example, a survey in late November 2020 found that 31% of adults said that allegations of voter fraud had been getting too little attention. After applying the retirement simulation and reweighting the data, this estimate was 32%. Other estimates, such as confidence in various institutions or whether people intend to get the COVID-19 vaccine, did not change at all. On average, the retirement changes survey figures based on all U.S. adults by less than 1 percentage point. In instances where the retirement does move estimates, the change is typically a small increase in support for a Republican-leaning viewpoint.

Researchers also examined how the retirement affects estimates based on key subgroups (e.g., race, ethnicity, political party, sex). For nearly all the groups examined, the retirement moves estimates very slightly or not at all. For example, estimates for Black, Latino, or Asian adults moved by just 0.2, 0.4, and 0.3 percentage points on average, respectively. The effect from retirement was, however, more pronounced for White college graduates. Adults in this group are among the most overrepresented on the ATP and, thus, the most likely to be retired. Estimates for White college graduates moved by 2.2 percentage points on average after applying the retirement. For example, in the late November 2020 survey, 42% of White college graduates reported feeling comfortable eating out in a restaurant, given the situation with the coronavirus outbreak. After applying the retirement, this rate increases to 45%. While these changes to ATP estimates are not big and dramatic, they do subtly increase measured support for Republican-leaning viewpoints.

One downside of the retirement strategy is that it results in a slight understatement of standard errors for ATP estimates. This is because the ATP weights are not modified to account for the retirement. In testing where researchers did modify the weights, all the overrepresentation in the ATP that the retirement is designed to eliminate was reintroduced, and the improvements to estimates disappeared. After the retirement is implemented later this spring, ATP weighting and standard errors will continue to account for differential probabilities of selection in recruitment and differential nonresponse, but they won’t include an additional adjustment for the retirement.

In sum, the retirement of overrepresented panelists has only a subtle effect on estimates. This comports with Center research finding that modest differences in a survey’s partisan balance have little effect on public opinion estimates. However, when the retirement does have an effect, there tends to be a slight increase in support for Republican-leaning viewpoints. To be sure, the “truing up” from the retirement will only last so long. Over time, people’s decisions about joining the panel and continuing to participate will take their effect. The greater willingness of certain adults to participate in surveys is a strong societal force that will be hard to fix precisely. Therefore, the panelist retirement is one of several strategies the Center is pursuing.