Previous studies have shown that Americans’ levels of political awareness relate closely to their news media habits. The findings here reveal that political awareness – which is based on how politically knowledgeable one is and how closely one follows politics – impacts perceptions and behaviors around the issue of made-up news and information. Highly politically aware Americans tend to see it as a bigger problem and think it has a greater impact on the democratic system. They also say they come across this type of information more often, though it is the less politically aware who are more likely to spread it. Additionally, the steps the two groups take in response to made-up news seem to reinforce their level of awareness. The highly politically aware are more likely to take more actions overall in response to made-up news, but the less politically aware are more likely to tune out news altogether.

Political awareness is not connected in any substantial way to party identification. Highly politically aware adults make up about equal portions of both major parties – 33% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents and 32% of Democrats and Democratic leaners. But the highly aware adults tend to be older and have a higher level of education than those who are less politically aware. Overall, the findings between the highly and less politically aware persist even when taking these age and education differences into account.

Political awareness is based on answers to three political knowledge questions and one question about how closely respondents say they follow what’s going on in government and public affairs. The “highly politically aware” are those who correctly answered all three knowledge items and say they follow politics most of the time – 31% of respondents. The “less politically aware” are the 41% who did not answer all three correctly (i.e., got at least one wrong) and say they follow politics less often. The remaining 27% fall in between and are termed the “somewhat politically aware.” Individuals in this group either follow politics most of the time or answered all three correctly, but not both. Across the views and behaviors around the issue of made-up news, the somewhat politically aware mostly fall somewhere in between the highly aware and the less aware, though they occasionally fall closer to one group or the other. The findings in this section show the results comparing the “highly” and “less” politically aware. For a look at the findings that including the “somewhat” aware, see Appendix.

The highly politically aware see a greater impact of made-up news and information on the democratic system than the less politically aware

The highly politically aware are more likely than the less politically aware to say that made-up news has a big impact on four of five aspects of our society and democratic system asked about, including Americans’ confidence in government institutions and in each other, politicians’ ability to get work done and the public’s ability to solve community problems. For example, about eight-in-ten of the highly politically aware (78%) say made-up news and information has a big impact on Americans’ confidence in government institutions, compared with 57% of the less politically aware.

The highly politically aware are more likely than the less politically aware to say that made-up news has a big impact on four of five aspects of our society and democratic system asked about, including Americans’ confidence in government institutions and in each other, politicians’ ability to get work done and the public’s ability to solve community problems. For example, about eight-in-ten of the highly politically aware (78%) say made-up news and information has a big impact on Americans’ confidence in government institutions, compared with 57% of the less politically aware.

The two groups’ views converge on the issue of whether made-up news impacts journalists’ ability to get the information they need.

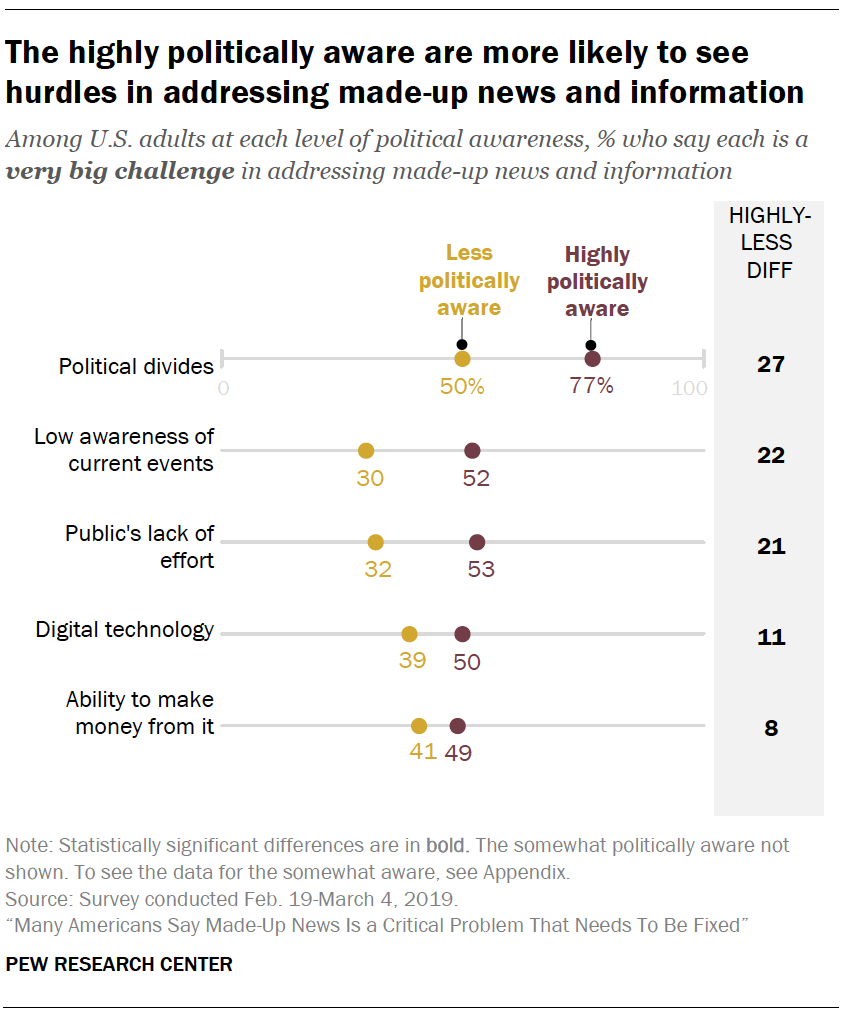

The highly politically aware also see greater hurdles to addressing the issue of made-up news and information and are more likely to see it getting worse.

The highly politically aware also see greater hurdles to addressing the issue of made-up news and information and are more likely to see it getting worse.

When asked about potential challenges to finding a solution to made-up news, the highly politically aware are more likely than the less politically aware to think that several issues represent very big challenges. For example, about three-quarters of the highly politically aware (77%) say political divides are a very big challenge to finding a solution, 27 percentage points higher than those who are less politically aware (50%). Large differences between the groups emerge for two of the other challenges asked about – low awareness of current events (52% of highly politically aware see it as a very big challenge compared with 30% of the less aware) and the public’s lack of effort (53% vs. 32%, respectively).

As for the future of made-up news, almost two-thirds of the highly politically aware (64%) think it will get worse in the next five years, compared with half of the less politically aware.

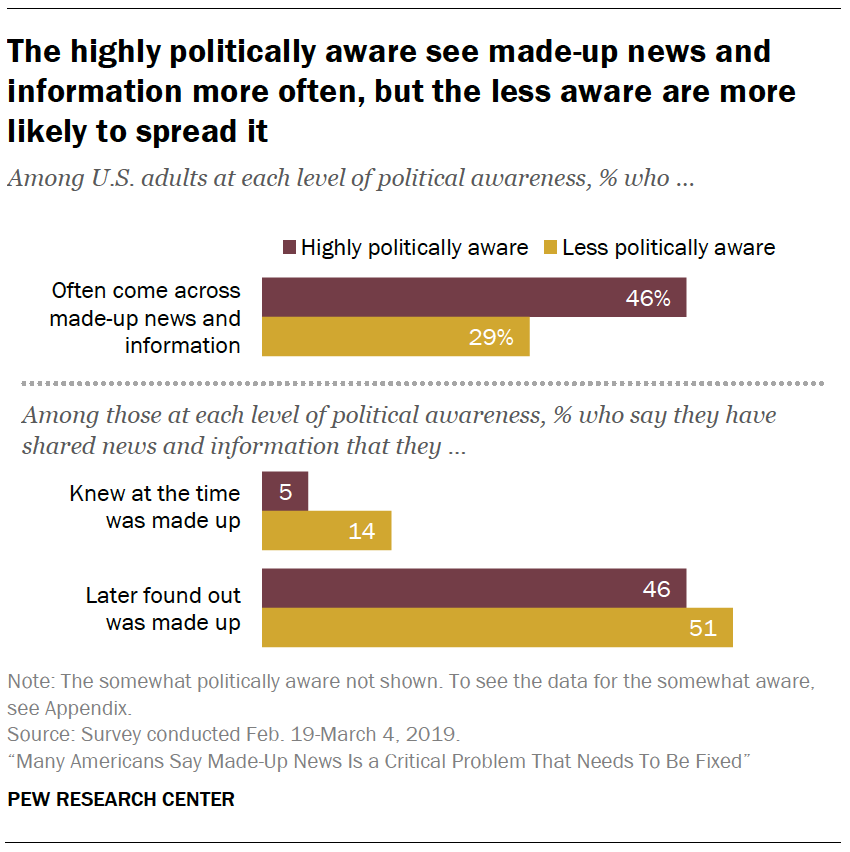

While the highly politically aware are more likely to see made-up news and information, the less aware are more likely to spread it

Not only are the highly politically aware more concerned about made-up news and information, they also say they see it more frequently than the less politically aware. Just under half of the highly aware (46%) report that they often see made-up news and information, compared with 29% of the less aware. This finding is likely tied to their broader news habits, as the highly politically aware generally follow news more closely.

Even though the highly politically aware see made-up news more often, the less politically aware are more likely to spread it. Few Americans overall (10%) report that they purposely share made-up news, but that number moves up to 14% of the less politically aware who have shared news and information that they knew was made up. That makes them about three times as likely to knowingly share made-up news as the highly politically aware (5%).

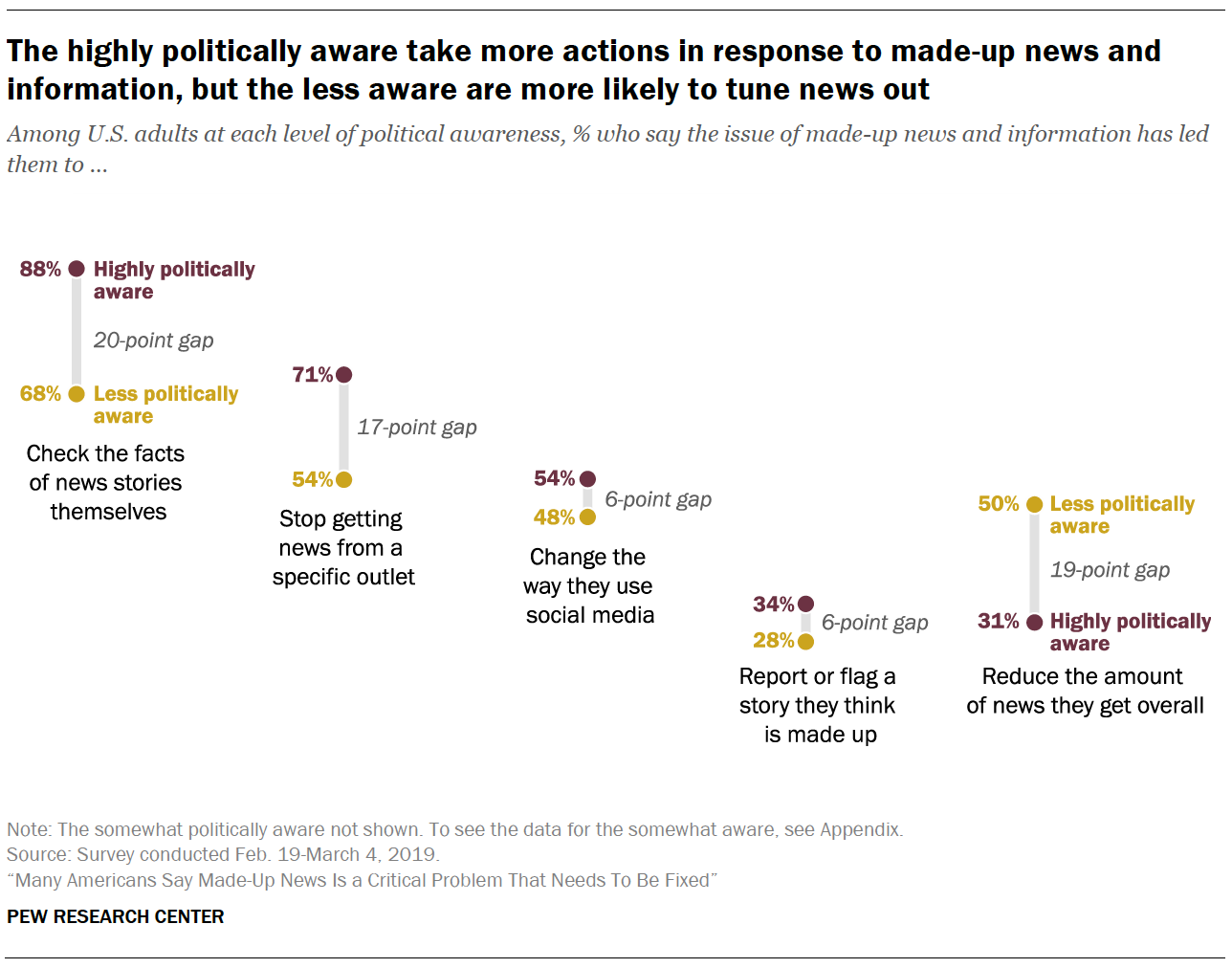

The highly politically aware take more actions in response to made-up news; the less aware are more likely to reduce their news intake

Overall, the highly politically aware are more likely to have undertaken four of five actions in response to made-up news asked about. One of the biggest differences in the groups’ responses to made-up news is that about seven-in-ten of the highly aware (71%) say they have stopped getting news from a specific outlet, compared with 54% of the less aware.

The gap around the decision to reduce overall news consumption is about the same size – but with the less politically more likely to have done so. While about three-in-ten of the highly politically aware (31%) have taken that action in response to made-up news, fully half of the less aware say they have reduced the amount of news they get. This response by the less aware is in line with their news habits more generally: They already tend to follow the news less closely and respond to made-up news by withdrawing further from the news.

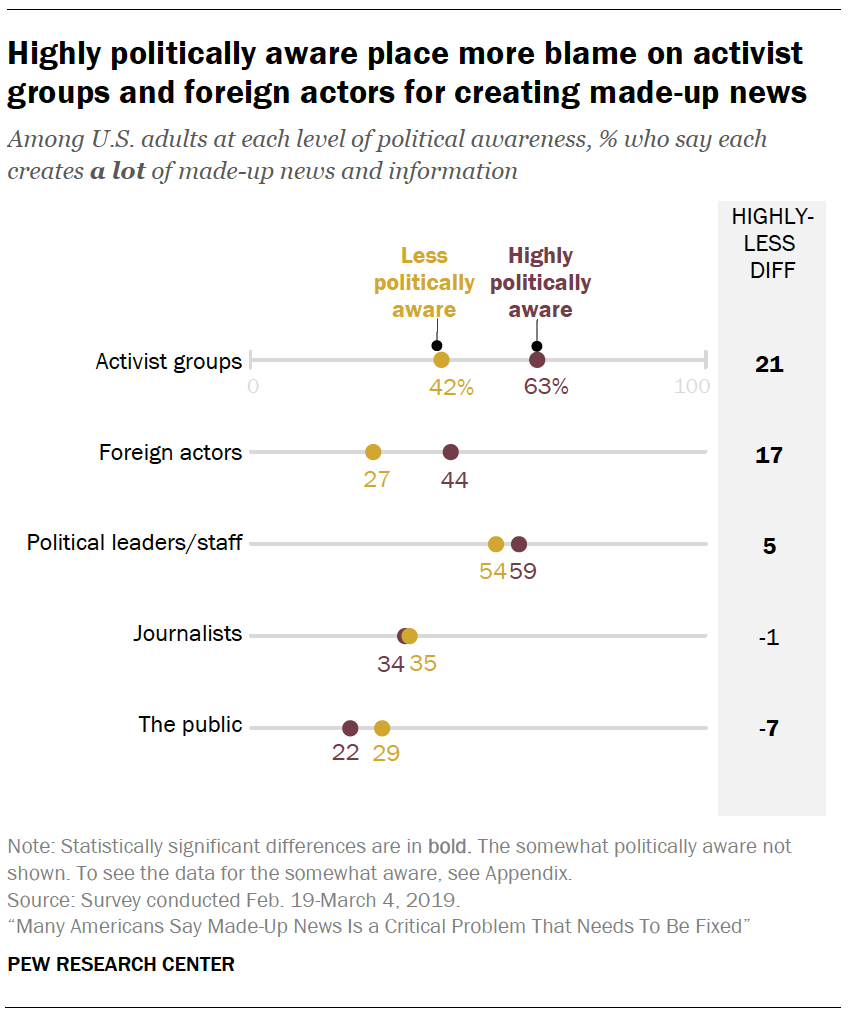

The highly politically aware place more blame than the less aware on activists, foreign actors; majorities of both see political gains as a driver

Both the highly politically aware and the less politically aware rank political leaders and their staff, as well as activist groups, as the leading culprits in creating made-up news and information. But there are differences in degree. Roughly two-thirds of the highly politically aware (63%) say activist groups produce a lot of made-up news, 21 percentage points higher than the less politically aware. There is a far smaller difference between both groups in the blame they place on political leaders and their staff (59% of the highly aware vs. 54% of the less aware).

Both the highly politically aware and the less politically aware rank political leaders and their staff, as well as activist groups, as the leading culprits in creating made-up news and information. But there are differences in degree. Roughly two-thirds of the highly politically aware (63%) say activist groups produce a lot of made-up news, 21 percentage points higher than the less politically aware. There is a far smaller difference between both groups in the blame they place on political leaders and their staff (59% of the highly aware vs. 54% of the less aware).

There is also a considerable divergence when citing foreign-based individuals and groups for creating a lot of made-up news (44% for the highly politically aware vs. 27% for the less aware).

Overall, large segments of both groups see political goals as a major reason why people create made-up news, and that view is virtually unanimous among the highly politically aware, with 98% saying this. That compares with a still robust three-quarters of the less politically aware. The less aware are more likely to think a major reason why people create made-up news is for fame and to be funny – though small minorities of both groups say comedy is a major reason.

As for finding a solution to the problem of made-up news, about half of both groups think the news media bear the largest responsibility to reduce it (52% of the highly politically aware and 51% of the less politically aware). This is far higher than the portion in each group who place responsibility on the public, government and technology companies.