by Atiba Pertilla and Todd belt

For years, news consultants have told broadcasters that the spinach in local TV news mattered, too. Certainly they advised clients about whom to hire, how to write teases, and even the most audience-friendly hairstyles. But they also warned that while gimmicks can get viewers to sample a station, it's content that keeps them.

Today, in harder times, newsrooms have more problems than ever – budget pressures, the transition to digital technology, declining viewership, and now the likely coming of duopoly and cross-ownership takeovers, are only a few.

The only thing the newsroom still absolutely controls is what it puts on the air.

It turns out that the consultants were right – content does matter.

A five-year study of local television that analyzed more than 1,200 hours of news and more than 30,000 stories suggests that by several measures quality, as defined by broadcast journalism professionals, is the most likely path to commercial success, even in today's difficult economic environment.

How do we know?

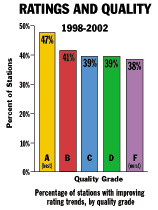

In the first three years, we used ratings as our proxy for economic success. We created a three-year ratings trend – 12 Nielsen ratings books – to determine whether stations were gaining or losing viewers over time. In all, we found that 47 percent of stations with the highest quality – "A" stations – were experiencing ratings success, a higher percentage than in any other grade.

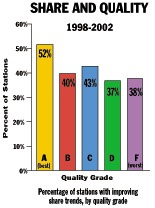

Meanwhile, we have also gathered data on share – the percentage of all television sets in use that are watching a program – as another measurement of commercial success. Here the data from the last five years show that 52 percent of "A" stations were building market share over time, a better record than in any other quality grade.

And for share, the quality argument is even stronger than for ratings. Not only did the very best stations fare better, but even a little quality helped. The higher a station's quality score, the better its gain in market share was likely to be.

Still, some questions remained. For the last two years, for example, "A" stations were not the grade category most likely to show ratings success. In fact, this year "D" stations fared best, while last year it was "B" stations.

With local news ratings nearly everywhere falling, has the relationship between quality and commercial success weakened? Or is it that ratings alone no longer adequately reflect commercial success?

Broadcasters themselves have begun to use new measurements, and for the last two years the study has collected data for two of them: viewer demographics and audience retention.

Most programs – news and entertainment – now rank themselves by how many viewers they get between the ages of 18 and 54, the demographic valued most by advertisers.

In addition, keeping or even adding to the audience a broadcast inherits from earlier programming, the so-called lead-in, has also become nearly as important as ratings. (One trade publication ad boasted of a court show's ability to gain 15 percent on its lead-in – even though this added up to just a lowly 3.9 rating for the station in question.)

These additional measures make an even stronger case for quality. Stations that did the best job of keeping or adding to their lead-in audience also scored high for quality (380 points on average). Stations that did a poor job of retaining their lead-in scored lower for quality (they average 339).

This is what researchers call a straight-line correlation. Even a small boost in quality is likely to help a station retain more lead-in audience.

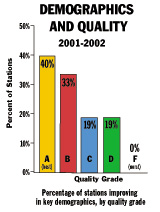

What about demographics? Here too, it appears that quality works, though the statistical relationship is not quite as strong as for lead-in. Stations with the best demographic trends – more of that key 18-to-54 audience – averaged a solid "B" for quality. The stations with the worst trends managed only a "C."

What if you tie these measurements together? We created a Viewership Index by combining two years of ratings data with the new measurements of audience retention and demographics (adding share tends to skew the results since ratings and share measure similar numbers). Once again, we found what academic researchers call a statistically significant relationship between quality and commercial success.

In other words, quality seems to help across the board. While many factors influence viewership – from anchor chemistry to promos and teases – quality journalism is not just incidental. It's actually good business.

Unfortunately, the conventional wisdom is tempting local newsrooms in a different direction. The success of new genre shows like Survivor has reinforced the sense that younger viewers are turned off by traditional programming and want something different.

In news, one response has been to create broadcasts that are "fast-paced" and "lifestyle-oriented." Take, for example, the marketing campaign for The Daily Buzz, a syndicated morning news program that premiered in the fall of 2002. It touted the new entry by declaring that its audience would skew younger than the morning shows on the Big Three networks. "This show will be edgier and funnier, while providing news content that is relevant to the younger generation," one news executive declared in a company press release.

But there are few successful examples of this "edgier" approach to TV news connecting with younger viewers. We studied one example, WAMI in Miami, in 1999, and noted that it suffered from "too many out-of-town feeds, poor sourcing, and low community relevance." WAMI's newscast was later shut down after less than three years on the air.

The evidence suggests that younger people want the same thing most viewers do – and that, believe it or not, is quality.

All this should be reason for optimism. Content is the one thing news directors can control. The first challenge is to believe the hard numbers, not the mythology. The second challenge is to learn how to produce more quality with fewer resources. If that doesn't happen – and happen soon – local TV news may be in more danger than newspapers of becoming irrelevant. It is certainly losing more audience, and losing it faster.

Atiba Pertilla is a research associate at PEJ. Todd Belt is a doctoral candidate in political science at the University of Southern California.