Even as Americans who primarily get their political news on social media are less likely to follow most news topics and be aware of specific events in the news, people in this group are as aware – or sometimes more aware – of several unproven claims and fringe theories related to the COVID-19 outbreak.

Even as Americans who primarily get their political news on social media are less likely to follow most news topics and be aware of specific events in the news, people in this group are as aware – or sometimes more aware – of several unproven claims and fringe theories related to the COVID-19 outbreak.

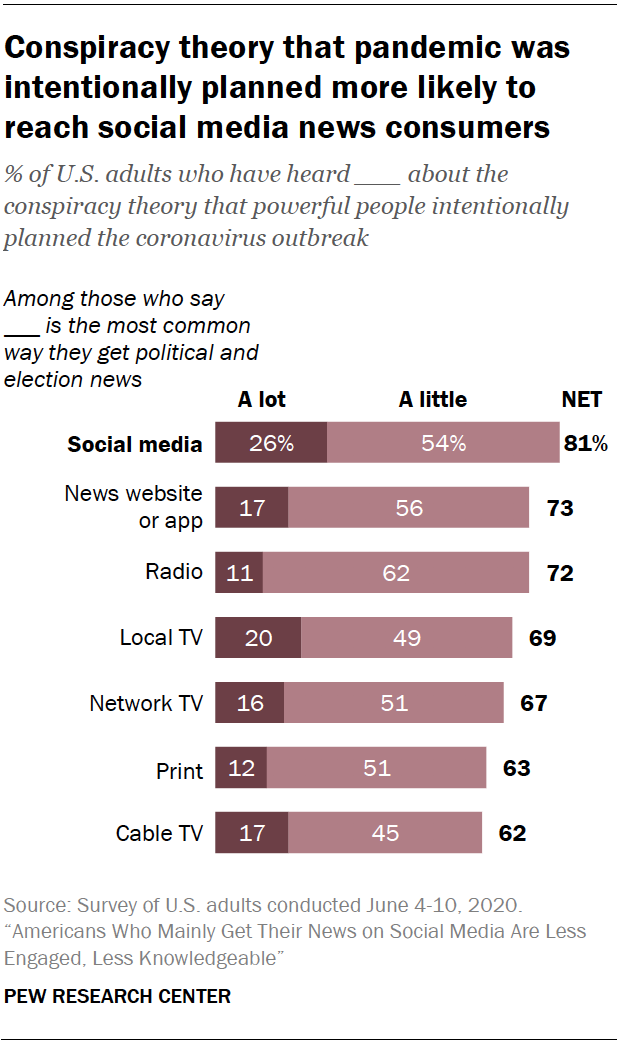

One clear example is exposure to the conspiracy theory that powerful people intentionally planned the pandemic, a theory that gained attention with the spread of a conspiracy video on social media. About eight-in-ten U.S. adults who get most of their news through social media (81%) have heard at least “a little” about this theory, including about a quarter (26%) who have heard “a lot” about it. That is more than among those who turn to any of the other six platforms for their political news.

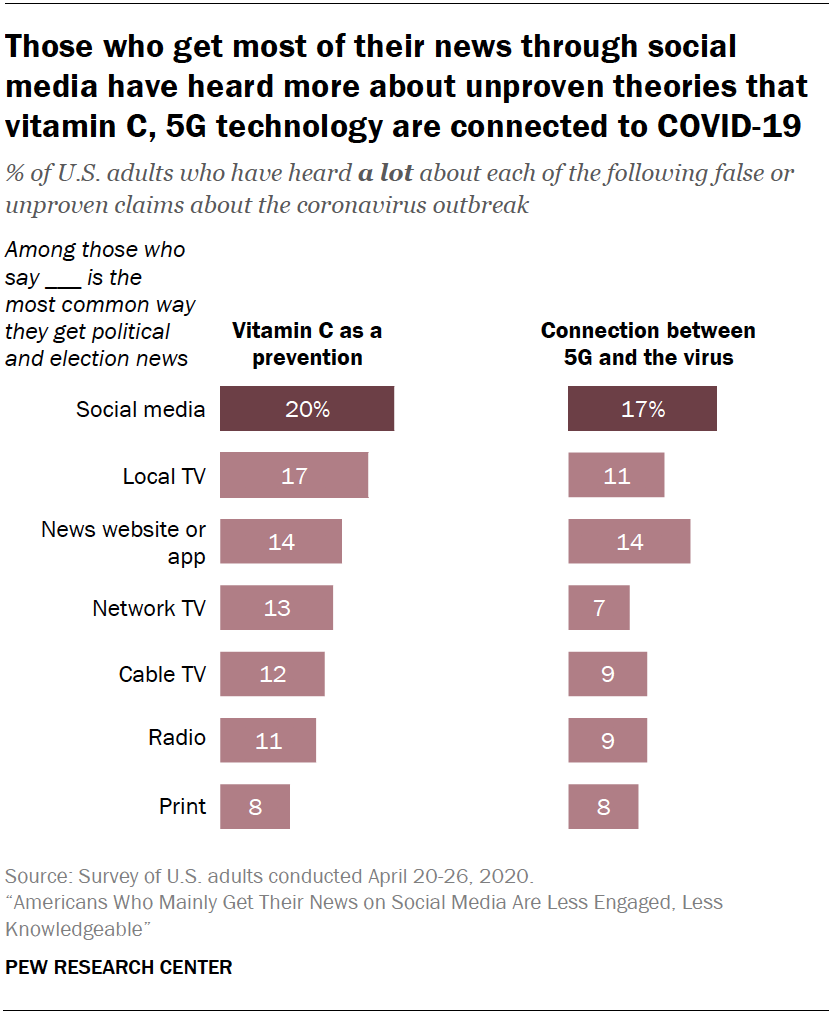

Furthermore, when asked in April about a list of topics connected to the coronavirus, Americans who get their news primarily through social media were more likely than most other groups to have heard about two unproven ideas: that taking vitamin C would prevent COVID-19 and that there is a connection between the virus and 5G mobile technology.

Furthermore, when asked in April about a list of topics connected to the coronavirus, Americans who get their news primarily through social media were more likely than most other groups to have heard about two unproven ideas: that taking vitamin C would prevent COVID-19 and that there is a connection between the virus and 5G mobile technology.

At the time, one-in-five of those who get their news through social media had heard “a lot” about taking vitamin C as a preventative measure, about on par with those who turn to local TV but higher than for those who rely on any other platform for political news. And about the same share (17%) had heard of a connection between 5G technology and the virus, again higher than most other groups.

There are other claims about possible COVID-19 treatments and preventions, though, that those who get most of their political news through social media had been less likely to hear about. This may be related to where each of these storylines was commonly discussed. For example, the social media group had heard less about the unproven claim that the drug hydroxychloroquine could be a treatment for the virus2, a claim discussed frequently by the president and covered by the national media, and they also had heard less than other groups about plasma transfusions, a possible treatment initially explored by scientists in early March.

More generally, when asked in March whether they had seen misinformation about the COVID-19 outbreak, those who get their political news from social media were the most likely group to say they had seen at least some misinformation. More than half (57%) said this in March, versus 49% or fewer among the groups turning to other platforms. When this question was asked again in April, increases occurred across all media news groups, but the social media group was still more likely than most to say they had seen coronavirus misinformation (68%), with the exception of those who turn to news websites and apps (73%) and radio (72%).

In some cases, those who get news through social media are more likely to believe unproven claims.

In some cases, those who get news through social media are more likely to believe unproven claims.

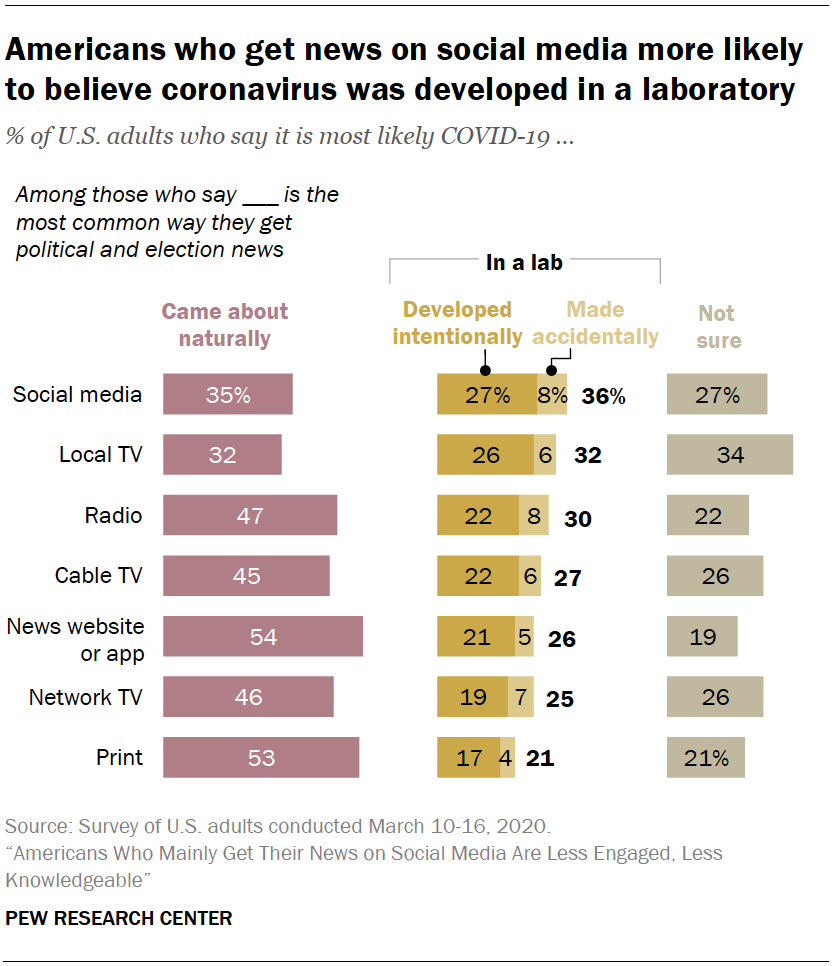

In March, those who get most of their news through social media were more likely than other U.S. adults to say that the COVID-19 virus was developed intentionally in a laboratory, and less likely than most other groups to say that the virus came about naturally. (The virus is believed to have originated naturally, though the way that it may have jumped from animals to humans is still being investigated.) About a third of this group (36%) said that the virus was made either intentionally or accidentally in a laboratory, higher than the share among those who turn to several other sources for their political news.

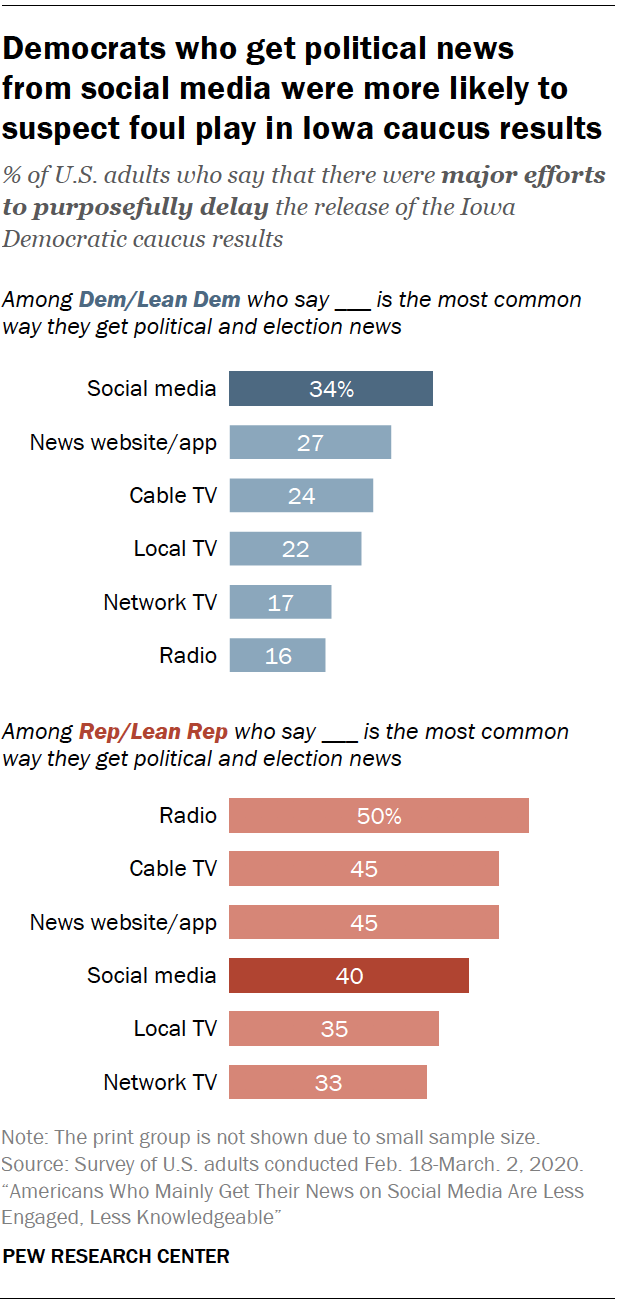

Finally, even as those who get political news mainly through social media were paying less attention to the 2020 campaign overall compared with other groups, they were more likely to give credence to an unsubstantiated theory during the Democratic primary – particularly among Democrats and independents who lean Democratic.

Finally, even as those who get political news mainly through social media were paying less attention to the 2020 campaign overall compared with other groups, they were more likely to give credence to an unsubstantiated theory during the Democratic primary – particularly among Democrats and independents who lean Democratic.

Among Democrats, those who get the bulk of their news from social media were the most likely to say that there were major efforts to purposefully delay the release of results from the Iowa Democratic caucus (34%), an unproven theory promoted on social media in early February. The same pattern was not seen among Republicans, who were overall more likely to accept this theory.

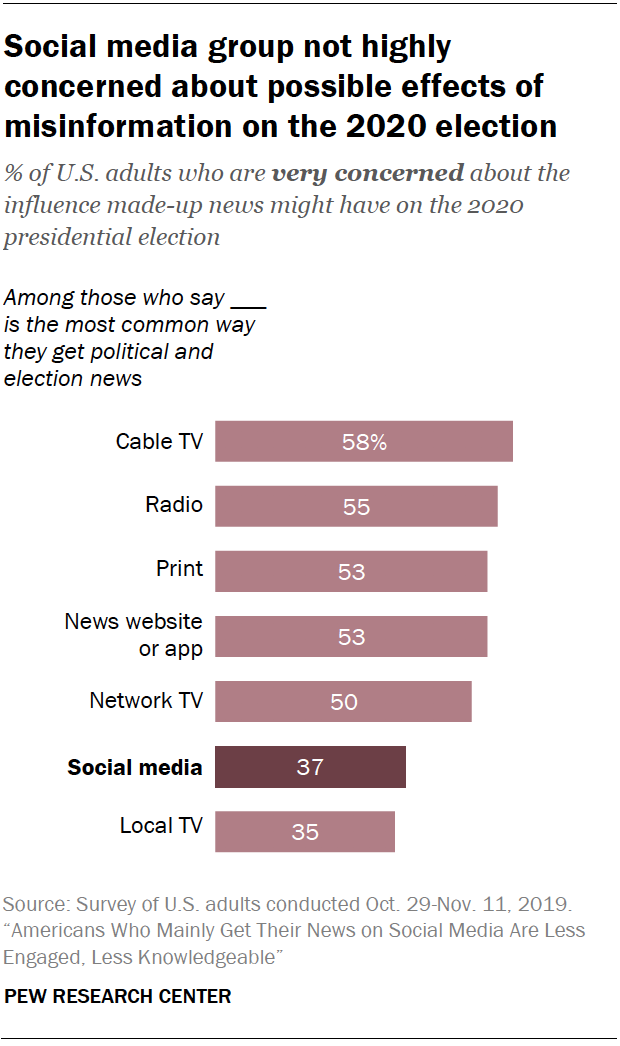

While those who turn to social media are more aware of – and in some cases more likely to believe – certain unproven claims or misinformation, this doesn’t translate to more concern about the effects made-up news can have. In a November survey, this group was actually less likely to be concerned about the effects made-up news may have on the 2020 election.

While those who turn to social media are more aware of – and in some cases more likely to believe – certain unproven claims or misinformation, this doesn’t translate to more concern about the effects made-up news can have. In a November survey, this group was actually less likely to be concerned about the effects made-up news may have on the 2020 election.

Just over a third (37%) of those who rely on social media for political news said they were “very concerned” about the effects made-up news might have on the 2020 presidential election, lower than for all other groups except those who get political news from local TV. By contrast, half or more of those who get most of their news through other platforms said they were very concerned about misinformation in the news ecosystem and its possible impact on the presidential election.