Discussions about the issue of made-up news and information are often framed in the context of social media, a news pathway that younger Americans gravitate to much more frequently than older Americans. On the whole, the youngest U.S. adults and those who prefer social media for their news feel less unease about made-up news and information. The youngest adults – those ages 18 to 29 – are less likely than Americans 50 and older to think made-up news has an impact on the democratic system or that the issue will get worse in the future. They are also less likely to say they frequently come across made-up news. But these differences are not as large as the divides by political party and political awareness discussed in previous sections.

Likewise, those who prefer to get their news on social media are less likely to think the issue will get worse than those who prefer other pathways to getting news, such as print newspapers or the television set. Additionally, they are no more likely to say they encounter made-up news than those who prefer other pathways, but they are more likely to share it.

Previous research has consistently shown that younger American adults rely far more heavily on social media for their news than those older than them. Younger adults get news from these sites more frequently and across different topics, including politics and science.

For instance, 40% of 18- to 29-year-olds often get news from social media sites, compared with 30% of those ages 30 to 49 and 16% of those 50 and older. And when asked which pathway they prefer for their news, 30% of 18- to 29-year-olds say social media sites, compared with 15% of 30- to 49-year-olds and a mere 3% of those 50 and older.

The similar patterns across age and preferred news pathway in this section may in part be because those who prefer social media for news are much younger. Even so, the overall findings comparing those who prefer social media for news and those who prefer another pathway, such as print newspapers or the television set, persist even when taking age differences into account.

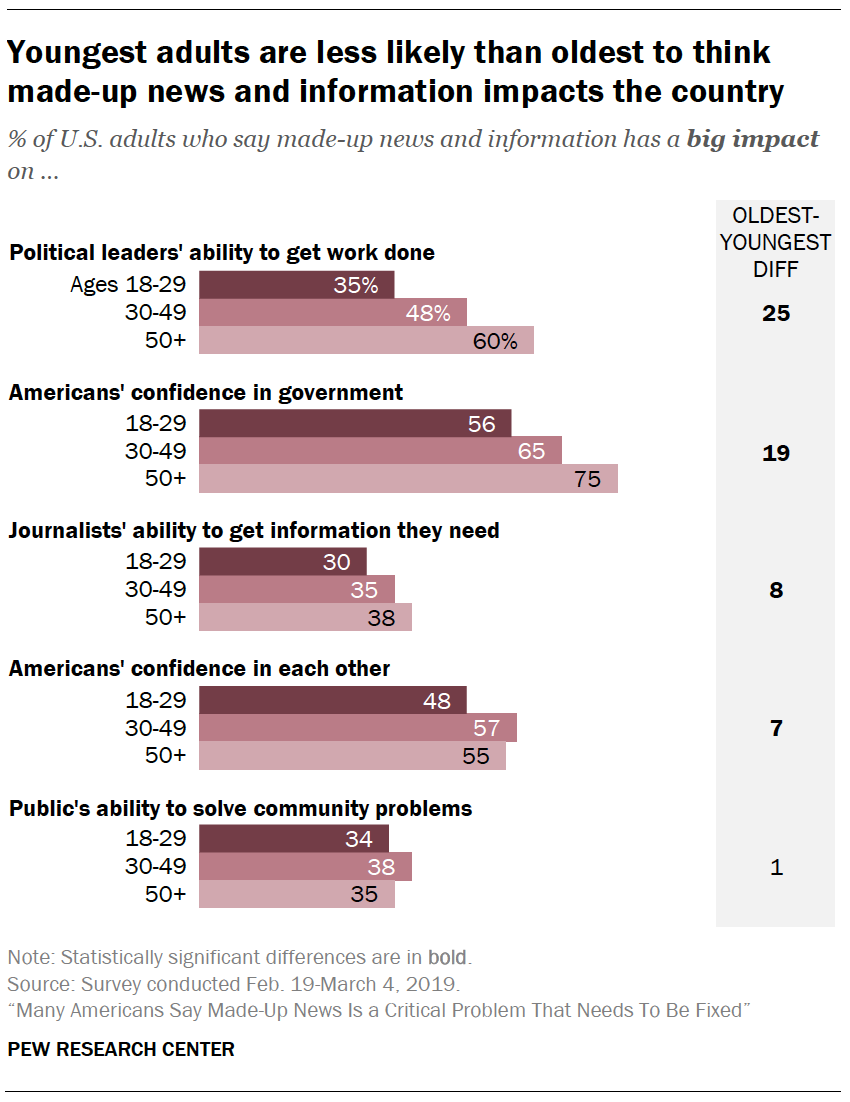

Youngest adults less likely than their elders to think made-up news and information has an impact on the democratic system

The youngest U.S. adults – those ages 18 to 29 – have less concern about the impact of made-up news and information on the democratic system than those older than them.

The youngest U.S. adults – those ages 18 to 29 – have less concern about the impact of made-up news and information on the democratic system than those older than them.

For example, roughly one-third of 18- to 29-year-olds (35%) say it has a big impact on political leaders’ ability to do their work, far lower than the 60% of those 50 and older who say this, with 30- to 49-year-olds falling in between. Similarly, while a little more than half of the youngest age group (56%) say made-up news has a big impact on confidence in government, this rises to three-quarters among those 50 and older.

Younger Americans also express less concern about the confusion that made-up news creates among the public. Six-in-ten of those ages 18 to 29 say it causes a great deal of confusion, compared with roughly seven-in-ten of those ages 50 and older (72%).

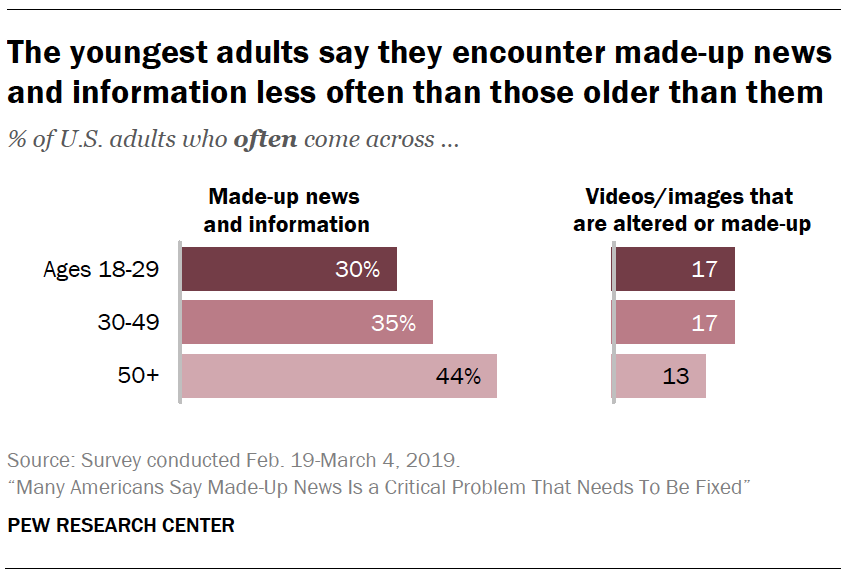

The youngest age group’s lower level of concern about made-up news reflects their lower level of exposure they say they have. The youngest group is also less likely than the oldest group to blame some key actors for creating made-up news.

The youngest age group’s lower level of concern about made-up news reflects their lower level of exposure they say they have. The youngest group is also less likely than the oldest group to blame some key actors for creating made-up news.

Three-in-ten 18- to 29-year-olds say they often come across made-up news, 14 percentage points lower than those 50 and older (44%) and modestly lower than 30- to 49-year-olds (35%).

Three-in-ten 18- to 29-year-olds say they often come across made-up news, 14 percentage points lower than those 50 and older (44%) and modestly lower than 30- to 49-year-olds (35%).

Younger adults are also less likely to think that four of the five actors asked about create a lot of made-up news: politicians, activists, journalists and foreign actors. For example, while 37% of 18- to 29-year-olds say activist groups create a lot of made-up news, this rises to 63% among those 50 and older. The only group that the youngest adults put somewhat greater blame on is the public (30% vs. 23% of the oldest age group). But while the percentages differ somewhat, political leaders and activist groups rise to the top across the three age groups.

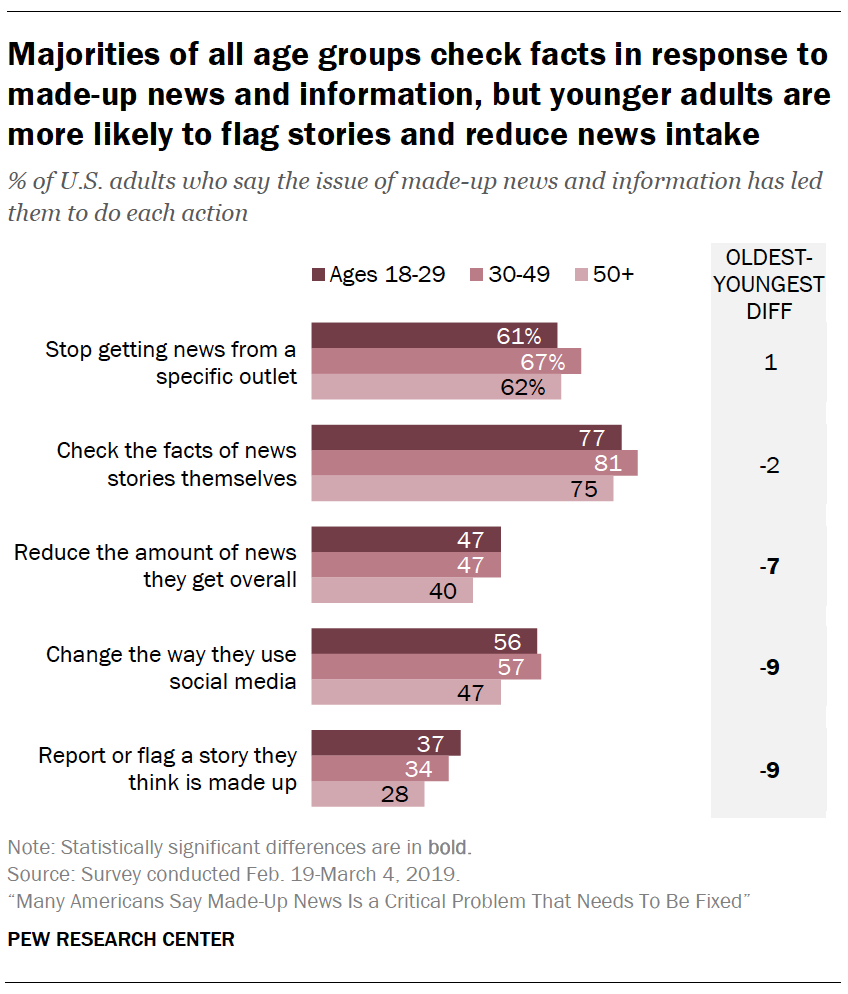

Despite their lower level of concern over made-up news, the younger age groups are more likely than the oldest group to have taken certain steps to combat it or to limit their exposure to it.

For example, about half of those ages 18 to 29 and 30 to 49 (both 47%) say made-up news and information has led them to reduce the amount of news they get overall, compared with four-in-ten adults ages 50 and over. These younger two groups are also more likely than the oldest group to have changed the way they use social media (56% and 57%, vs. 47%) or to flag or report a story they think is made up (37% and 34%, vs. 28%).

The most common action across the three groups is to check the facts of stories themselves. At least three-quarters of each group say they have done this in response to the issue of made-up news. And majorities of all three age groups also say that they have stopped getting news from a specific outlet as a response to made-up news.

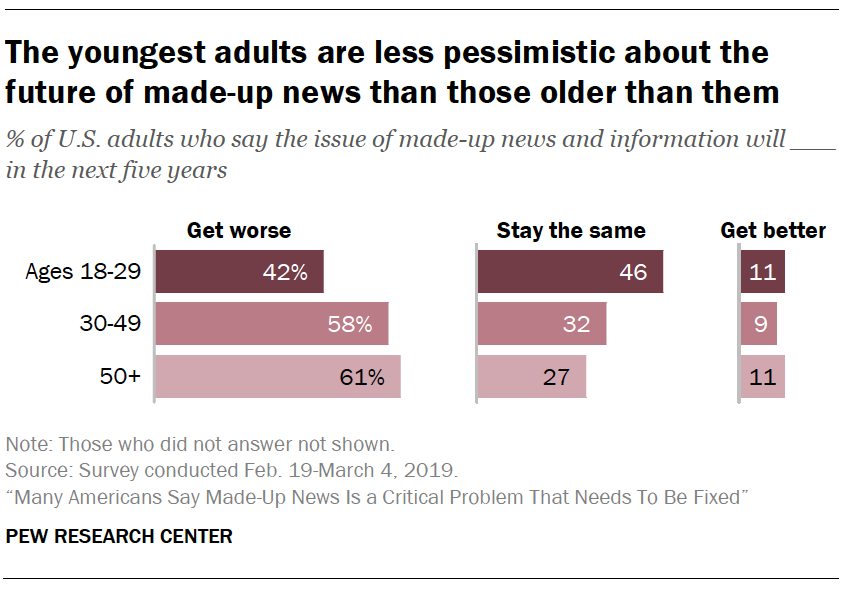

Youngest adults are less pessimistic about how the issue of made-up news will evolve, more likely to click through to made-up content

The youngest adults, those 18 to 29, stand out from the two older age groups in two other ways. First, they are less pessimistic about how the issue of made-up news and information will evolve. About four-in-ten 18- to 29-year-olds (42%) say the issue will get worse over the next five years, a notably smaller level of pessimism than registered by 30- to 49-year-olds (58%) or those 50 and older (61%). However, they are no more optimistic about seeing improvement than any other age groups, with about one-in-ten of each group thinking the situation will get better.

The youngest adults, those 18 to 29, stand out from the two older age groups in two other ways. First, they are less pessimistic about how the issue of made-up news and information will evolve. About four-in-ten 18- to 29-year-olds (42%) say the issue will get worse over the next five years, a notably smaller level of pessimism than registered by 30- to 49-year-olds (58%) or those 50 and older (61%). However, they are no more optimistic about seeing improvement than any other age groups, with about one-in-ten of each group thinking the situation will get better.

Second, 18- to 29-year-olds are more likely to click on links to news stories in social media they think are made-up. Among social media news consumers, about four-in-ten 18- to 29-year-olds (37%) do so at least sometimes, compared with roughly a quarter of those ages 50 and older (27%).

People who prefer to get news on social media share more made-up news and information than others and are less pessimistic about the future of the issue

Much of the discussion around made-up news and information is about how people see and engage with it on social media. Although much of the focus of made-up news is on how much it spreads on social media, those who prefer to get news that way are no more likely to say they often see it (36%) than those who prefer getting their news through other pathways (38%) such as print newspapers or the television set.

Much of the discussion around made-up news and information is about how people see and engage with it on social media. Although much of the focus of made-up news is on how much it spreads on social media, those who prefer to get news that way are no more likely to say they often see it (36%) than those who prefer getting their news through other pathways (38%) such as print newspapers or the television set.

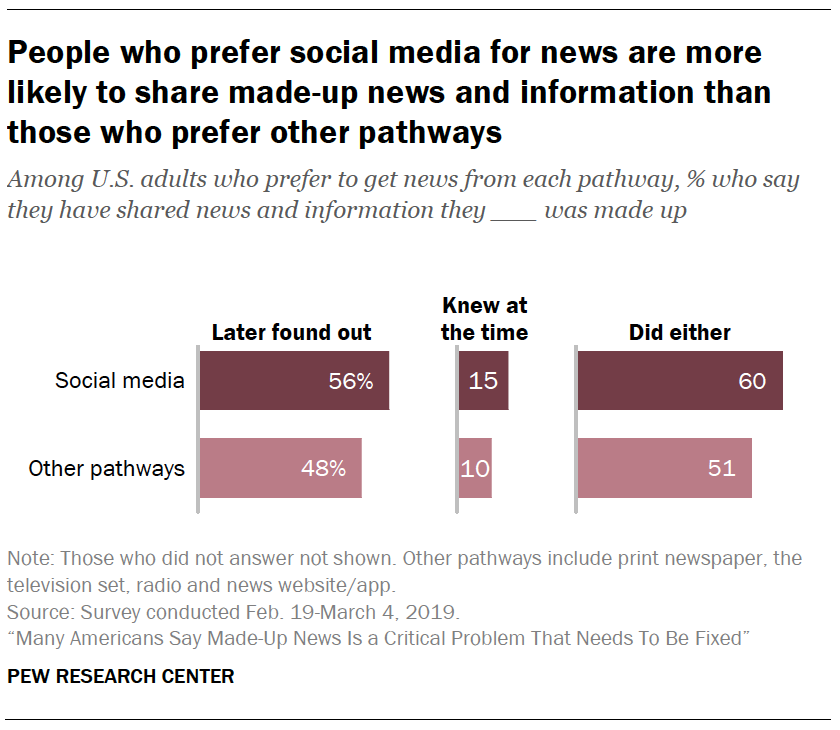

But even though they do not see made-up news more often, those who prefer to get news on social media are somewhat more likely to share it. More than half of those who prefer to get news on social media (56%) have shared news they later found out was made up, compared with about half of those who prefer other pathways (48%). They are also more likely to have shared news that they knew at the time was made up (15% vs. 10%).

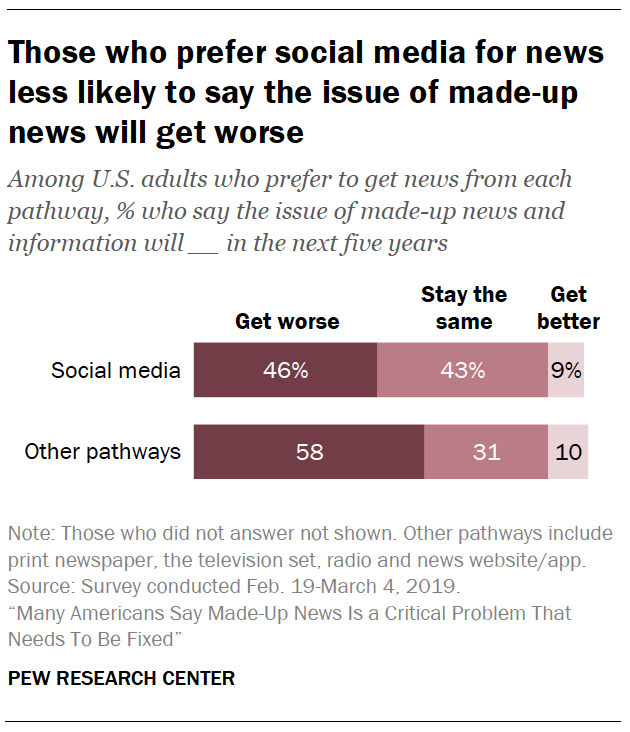

Aside from being more likely to share made-up news, Americans who prefer social media are less likely to think the problem will get worse in the future. Fewer than half of those who prefer social media for news (46%) think the issue of made-up news will get worse in the next five years, 12 percentage points lower than those who prefer other pathways (58%). Still, no more than one-in-ten of both groups say the problem will get better.