The populist divides seen in attitudes about the news media are not as prominent when it comes to the sources Western Europeans turn to for news.7

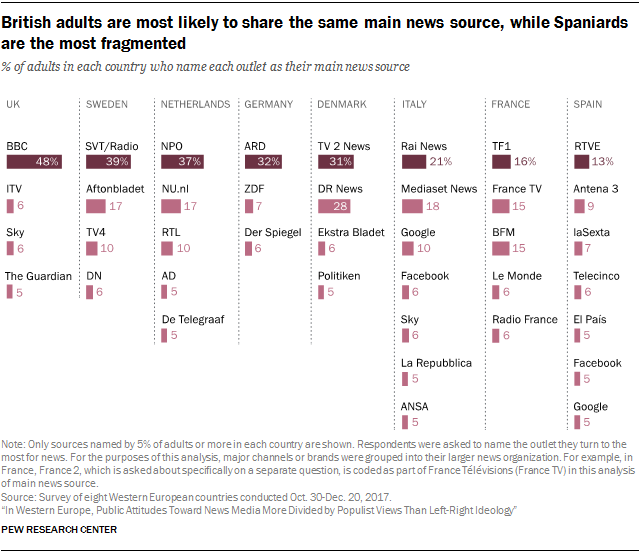

This survey also finds that news usage varies regionally. Southern, more than northern, Europeans are more fragmented, with left-right political differences more influential than populist leanings in shaping where people turn for news.8 Also, in five of the eight countries surveyed, at least three-in-ten or more adults share the same main news source. In the three southern countries, no more than 21% of adults name the same source as the primary one they use to get news.

Additionally, in all but one of the eight countries, the top-named main source for news is a public news organization rather than a private one. The one exception is France, where both a private organization, TF1, and a public one, France Télévisions, are named at about equal rates.9

People from southern European countries more fragmented in their main news source; for nearly all countries, public news organizations sit at the top

Five of the Western European countries studied in this report have a large portion of adults who share a common main source for news. At the high end are the UK, Sweden and the Netherlands, where 48%, 39% and 37% of adults, respectively, name the same main source for news: the BBC in the UK, Sveriges Television/Radio (SVT/Radio) in Sweden, and Nederlandse Publieke Omroep (NPO) in the Netherlands. In Germany and Denmark, about three-in-ten adults name the same source, including two public news organizations in Demark that both reach this level (TV 2 News and DR News). In France, Italy and Spain, however, audiences are more fragmented, with no more than 21% naming the same main source for news.

Another indicator of audience fragmentation is the number of outlets named as a main source by at least a small portion of the population. In other words, how wide of a mix of main news sources there is even if those sources are turned to by smaller pockets of people. In most countries, only a few outlets are named by 5% or more of the public. Germany has the fewest outlets that reach this threshold: The public broadcasting organization ARD (32% name it as their main news source), public-service TV broadcaster ZDF (7%), and the news magazine Der Spiegel (6%). Spain and Italy, on the other hand, stand out for having the most outlets named by at least 5% of adults: seven in each, including public news organizations in both countries (Radio y Televisión Española [RTVE] in Spain and Rai News in Italy), as well as Facebook and Google.

One consistent pattern across seven of the eight countries is that the most-named main news source is publicly owned, such as Rai News in Italy, the BBC in the UK and NPO in the Netherlands. This differs from the U.S., where even the largest public news outlets, NPR and PBS, are not used as universally as private news outlets. When U.S. voters named their main source for election news in 2016, NPR was only cited by 4% of Americans and PBS was cited by only 1%, placing them behind at least seven other news sources, including Fox News, CNN and Facebook.

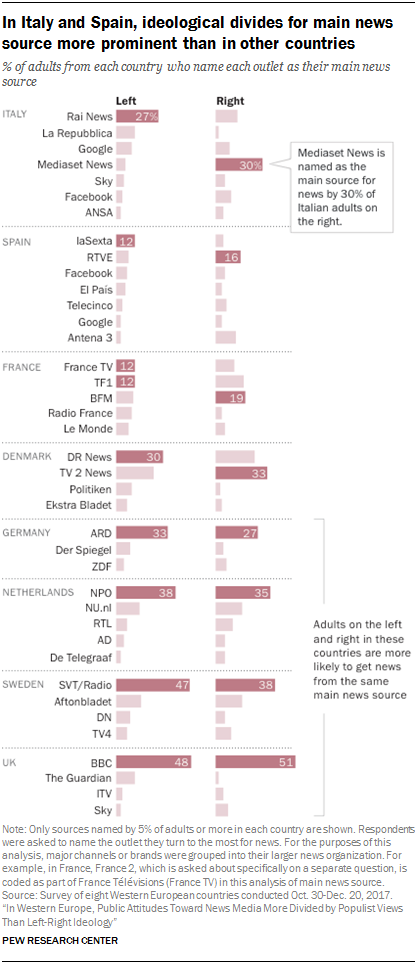

Spanish and Italian adults display ideological divides in main news source; other countries more unified

When it comes to main news sources, there is no consistent divide between those who hold and don’t hold populist views or between those on the left and right. When some divides do emerge, they tend be in the south. There, left-right divides over news sources are larger than those based on populist views.

When it comes to main news sources, there is no consistent divide between those who hold and don’t hold populist views or between those on the left and right. When some divides do emerge, they tend be in the south. There, left-right divides over news sources are larger than those based on populist views.

In Italy, for example, 30% of adults who place themselves on the right politically name Mediaset News as their main news source, compared with only 6% of adults on the left. The difference by populist views among Italian adults for Mediaset News is smaller: 24% of those who hold populist views vs. 11% of those don’t. And for Italy’s Rai News, 20% of both populists and non-populists name it as their main news source, compared with a left-right difference of 13 percentage points.

Spain also displays large left-right ideological divisions. RTVE, for example, is twice as popular as a main source for right-aligned adults (16%) as for left-aligned adults (8%). Meanwhile, those on the left are more likely to cite the TV station laSexta (12% vs. 5% of those on the right).

France and Denmark show some divide between adults on the left and right but less so than in Italy and Spain. In France, among the top main news sources, people on the left most often name France TV and TF1, while those on the right most often name BFM – though substantial portions on both sides use all three. In Denmark, both sides list the same top two main sources (DR News and TV 2 News).

The remaining four countries show a great deal of political unity in their main news sources. In the Netherlands, for example, none of the top-two main sources – NPO and NU.nl – show any ideological difference in use; both are cited at roughly the same rates by those on the left and those on the right. In Sweden, both sides are most likely to name SVT/Radio as their main source, followed by Aftonbladet, while Germans on the left and the right share ARD as their top source. The same is true in the UK with BBC as the shared top source.

Across range of nationally oriented news outlets, audiences in Western Europe tend to concentrate around ideological center

To get a better sense of the full extent of peoples’ news diets beyond their main news source, the survey also asked respondents in each country whether they regularly get news from each of eight specific news outlets. The sources were selected for a range of audience size, type of platform, funding (public vs. private), and appeal to different political groups (see Appendix A for a more detailed explanation on how outlets were selected).

Regular usage of these outlets follows the patterns seen in the main news sources cited by adults in those countries. In most countries the top main news source that people name also tends to have the largest audience of the eight outlets asked about.10

Regular usage of these outlets follows the patterns seen in the main news sources cited by adults in those countries. In most countries the top main news source that people name also tends to have the largest audience of the eight outlets asked about.10

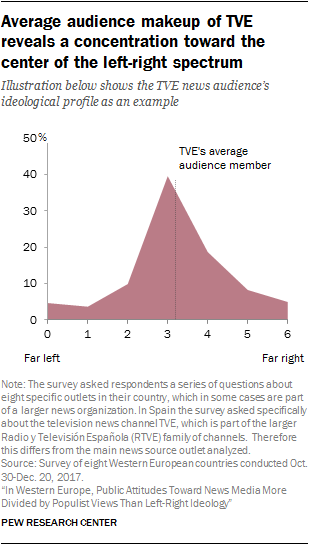

The lack of deep left-right ideological divides in usage of specific outlets is further revealed when examining outlets’ full audience profiles. Even for outlets that have greater usage among those on the left or those on the right, looking at the full audience profile of each outlet reveals that the average audience member for most outlets lands very close to the center of the left-right scale.

This can be explained by two things: 1) The often large portions of people on both sides of the political spectrum that use the outlet, even if one side tends to use it more than the other, and 2) That few adults in each country place themselves at the far ends of the ideological scale. This then pulls the ideological audience profile of each outlet closer to the middle (a 3 on the 0-to-6 scale) than to the ends.

For example, in Spain’s case, Televisión Española’s (TVE) audience (those who regularly use it) is more right-aligned than left-aligned (18% are on the left, 40% are in the center and 32% are on the right). Still, a plurality of the audience falls at a 3 on the left-right ideological scale (40%).

For example, in Spain’s case, Televisión Española’s (TVE) audience (those who regularly use it) is more right-aligned than left-aligned (18% are on the left, 40% are in the center and 32% are on the right). Still, a plurality of the audience falls at a 3 on the left-right ideological scale (40%).

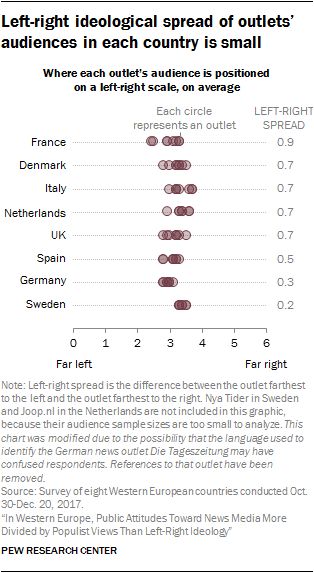

This pattern is true across all eight countries surveyed. The audiences of all the outlets in each country tend to cluster toward the middle of the left-right scale (3 in the 0-to-6 scale.)

In Sweden, where the left-right spread is the narrowest, for example, the average audience member for all outlets lands between 3.3 and 3.5 on the scale – a gap of just .2.11