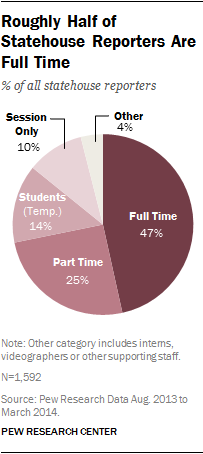

Altogether, the Pew Research Center identified 1,592 journalists who cover state government around the country. Of those reporters, 741 (47%) cover state government full time. For these journalists, the statehouse is their beat. They cover it every day and have the greatest opportunity to develop sources and produce stories that go beyond the basic contours of daily news. Most of them have desks in pressrooms within their state’s capitols or in buildings nearby. They usually cover many aspects of government, particularly the legislature, the governor, state agencies and departments and, sometimes, state courts.

Altogether, the Pew Research Center identified 1,592 journalists who cover state government around the country. Of those reporters, 741 (47%) cover state government full time. For these journalists, the statehouse is their beat. They cover it every day and have the greatest opportunity to develop sources and produce stories that go beyond the basic contours of daily news. Most of them have desks in pressrooms within their state’s capitols or in buildings nearby. They usually cover many aspects of government, particularly the legislature, the governor, state agencies and departments and, sometimes, state courts.

The data find slightly more reporters who work at the statehouse on less than a full-time basis—851 in all (53%).

Of those, 163 reporters—10% of the total—cover statehouses solely during legislative sessions. These session-only journalists report during the periods when statehouse news is most plentiful, when lawmakers are debating and voting on bills. Pew Research found that only 11 legislatures meet for an average of six months or more per session (and four meet only every other year), meaning that most of these session-only journalists spend less than half the year at the statehouse.2 The rest of the time, these reporters usually cover other assignments for their news organizations.

In addition, 402 journalists (one-quarter of the total) cover the statehouse part time. Often, they cover other assignments on a regular basis and are dispatched to the capitol when there is a big story or news on a particular topic they are covering.

There also are 223 college students—14% of the total statehouse press corps—who generally cover the statehouse for short periods of time, such as a semester. In all, 97 of these student reporters work for legacy organizations, such as newspaper or broadcast outlets or wire services. The remaining 126 cover the statehouse for university-based publications, nonprofits and even some specialty publications.

Several journalism schools have built statehouse reporting assignments into the curriculum. At the University of Maryland, broadcast bureau director Sue Kopen Katcef sees the journalism school’s Capital News Service as a “training ground” for aspiring journalists. Seniors and master’s degree students work several days a week to produce stories for outlets that subscribe to the news service. This spring, Katcef had five students covering the Annapolis statehouse.

Several journalism schools have built statehouse reporting assignments into the curriculum. At the University of Maryland, broadcast bureau director Sue Kopen Katcef sees the journalism school’s Capital News Service as a “training ground” for aspiring journalists. Seniors and master’s degree students work several days a week to produce stories for outlets that subscribe to the news service. This spring, Katcef had five students covering the Annapolis statehouse.

Other universities have more informal arrangements to give students statehouse reporting experience. The University of Montana, for instance, provides a scholarship and college credit for one student to spend a legislative session in Helena. The student’s articles are syndicated to nearly 40 newspapers—mostly weeklies and small dailies that cannot afford to have their own full-time reporters at the capitol. In addition, two broadcast students are assigned to another news service, which provides coverage to commercial radio and television stations throughout the state.

Finally, Pew identified 63 statehouse journalists who don’t fit into any of those categories or whose delineation in the data collection was unclear. Some are interns, although not student interns. Others are videographers or camera operators who work for broadcast outlets.

Across this mix, it is the journalists stationed at capitols year round who often bear the most responsibility for informing the public about the thousands of new state laws that are enacted each year. Because the federal government is divided and Congress today is often gridlocked, many people view state governments as the prime sources of legislative diligence in the United States.

“With gridlock in Washington, a lot of the action has shifted to statehouses,” said Darrel Rowland, public affairs editor of the Columbus Dispatch in Ohio’s capital city.

Numbers bear that out. The 112th Congress, which was in session during 2011 and 2012, passed 283 bills that were signed into law, according to records of the Library of Congress. During 2012 alone, California’s legislature passed 1,013 bills that became law, Michigan’s passed 948 and Louisiana’s legislature—which was in session for just 60 days—passed 870. In fact, 24 state legislatures—more than half of those that met in 2012—enacted more laws in that one year than Congress did in 2011 and 2012. Four state legislatures meet only in odd-numbered years.

Given this amount of legislative activity, several journalists expressed a need to be grounded in statehouse business full time, to maintain a constant presence in order to develop sources and keep tabs on officials.

“Anytime there are less people watching what’s going on, things are going to be slipping through the cracks,” said Garry Rayno, a statehouse reporter for the Manchester (N.H.) Union Leader. “Things that people should know are not getting reported.”