For the latest study of statehouse reporters, see “Total Number of U.S. Statehouse Reporters Rises, but Fewer Are on the Beat Full Time.”

For the latest study of statehouse reporters, see “Total Number of U.S. Statehouse Reporters Rises, but Fewer Are on the Beat Full Time.”

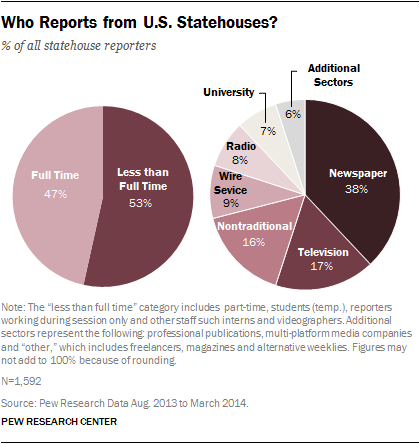

Within America’s 50 state capitol buildings, 1,592 journalists inform the public about the actions and issues of state government, according to new data from the Pew Research Center.

Of those statehouse reporters, nearly half (741) are assigned there full time. While that averages out to 15 full-time reporters per state, the actual number varies widely—from a high of 53 in Texas to just two in South Dakota. The remaining 851 statehouse reporters cover the beat less than full time.

In this study, statehouse reporters are defined as those physically assigned to the capitol building to cover the news there, from legislative activity to the governor’s office to individual state agencies.

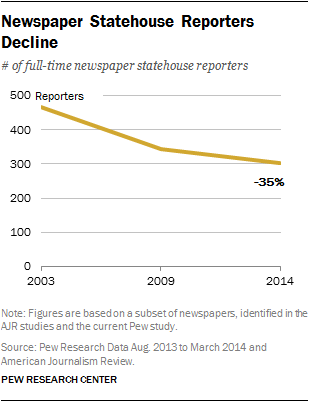

Newspaper reporters constitute the largest segment of both the total statehouse news corps (38%) and the full-time group (43%). But the data indicate that their full-time numbers have fallen considerably in recent years, raising concerns about the depth and quality of news coverage about state government.

Between 1998 and 2009, American Journalism Review conducted five tallies of newspaper reporters assigned to the statehouse full time. Each tally since 1998 showed decline. The most precipitous drop occurred between 2003 and 2009, coinciding with large reductions in overall newspaper staffing prompted by the recession and major changes in the news industry. To gauge the loss of reporters through 2014, Pew Research went back to the 2003 AJR list and examined statehouse staffing levels at newspapers that were accounted for in the last two AJR tallies—2003 and 2009 and in our 2014 accounting.1 Those papers lost a total of 164 full-time statehouse reporters—a decline of 35%—between 2003 and 2014. That percentage is slightly higher than the decline in newspaper newsroom staffing overall. According to the American Society of News Editors, full-time newspaper newsroom staffing shrunk by 30% from 2003 through 2012 (the latest year for which data are available).

As newspapers have withdrawn reporters from statehouses, others have attempted to fill the gap. For-profit and nonprofit digital news organizations, ideological outlets and high-priced publications aimed at insiders have popped up all over the country, often staffed by veteran reporters with experience covering state government. These nontraditional outlets employ 126 full-time statehouse reporters (17% of all full-time reporters). But that does not make up for the 164 newspaper statehouse jobs lost since 2003.

As newspapers have withdrawn reporters from statehouses, others have attempted to fill the gap. For-profit and nonprofit digital news organizations, ideological outlets and high-priced publications aimed at insiders have popped up all over the country, often staffed by veteran reporters with experience covering state government. These nontraditional outlets employ 126 full-time statehouse reporters (17% of all full-time reporters). But that does not make up for the 164 newspaper statehouse jobs lost since 2003.

The cutbacks have led to other changes as well. State officials themselves have attempted to fill what they say is a reduction in coverage by producing their own news feeds for public television, broadcast outlets or the Internet. Newspapers and other media have tried to compensate for the changes by hiring students and increasing collaboration among outlets. It is not uncommon these days for former competitors to share reporters or stories, a trend that would have been unheard of in years past.

Have additional data on statehouse reporting? Please share it with us to help inform the research.

To gather as complete of an accounting as possible of the nation’s statehouse reporting pool, Pew Research spent months reaching out to editors and reporters, legislative and gubernatorial press secretaries and other experts on state government. This report puts a first-ever number on statehouse reporters not just from newspapers, but from all media sectors. It details how they break down by state and media sector and looks at how those numbers relate to state demographics and legislative activity. For this report, the key requirement was that a statehouse reporter physically work in the state capitol building—whether full-time or less than full time.

Major findings of this study include:

- Less than a third of U.S. newspapers assign any kind of reporter—full time or part time—to the statehouse. According to the Alliance for Audited Media, only 30% of the 801 daily papers it monitor send a staffer to the statehouse for any period of time. In Massachusetts, whose capital is the largest city (Boston), just 6% of the state’s newspapers have any reporting presence at the statehouse—the lowest percentage of newspaper representation of any state.

- Fully 86% of local TV news stations do not assign even one reporter—full time or part time—to the statehouse. Of the 918 local television stations identified by BIA/Kelsey and Nielsen, just 130 assign a reporter to cover the statehouse. Overall, television reporters account for 17% of the total statehouse reporting pool and considerably less (12%) of the full-time mix.

- About one-in-six (16%) of all the reporters in statehouses work for nontraditional outlets, such as digital-only sites and nonprofit organizations. They also account for 17% of the 741 reporters who work at the state capitols full time. The largest statehouse bureau in the country, with 15 full-time staffers, is operated by the five-year-old Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, digital-only outlet. And in New York, the third most populated state, the largest bureau (with five full-time reporters) belongs to Capital New York, a commercial digital outlet founded in 2010.

- Students account for 14% (223 in all) of the overall statehouse reporting corps. Most students work at the statehouse part time and for short tenures. Many of these students (97) work for legacy outlets—newspapers, TV or radio stations, or wire services—while the other 126 work for outlets ranging from school newspapers to nonprofit news organizations.

- Wire services assign a total of 139 staffers to statehouses, representing 9% of all the reporters at the capitol buildings. The vast majority of full-time wire service reporters (69 of 91) work for the Associated Press. Although the wire service reduced statehouse staffing during the recession, the AP is now increasing the size of some of its capitol bureaus.

- Two indicators of the size of a statehouse press corps are the population of the state and the length of its legislative sessions. Of the 10 most populous states, all but two (Georgia and North Carolina) are among those with the 10 largest full-time statehouse press corps. And, eight of the 10 states with the longest legislative sessions also rank in the top 10 in the number of full-time statehouse reporters. Other potential factors—including demographic breakdowns, and the number of legislators per state—have no apparent association with the number of reporters assigned to cover a statehouse. (To access state-by-state data, click on this database)

While full historical comparisons on the number of statehouse reporters do not exist, the newspaper data reveal substantial decline over the past decade. And in numerous conversations with journalists, legislative leaders and industry observers, one sentiment was expressed again and again: concern about the impact of what they see as a broad decline in mainstream media coverage.

“I do think there’s been a loss in general across the country, and that’s very concerning to me,” said Patrick Marley, who covers the Wisconsin statehouse for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. “We have scads of reporters in Washington covering every bit of news that Congress makes. State legislators have more effect on people’s daily lives. We need to have eyes on them, lots of eyes.”

“I think you’re seeing fewer stories,” said Gene Rose, the longtime former communications director for the National Conference of State Legislatures. “The public is not being kept aware of important policy decisions that are being made that will affect their daily lives.”

The reality—at least for the foreseeable future—is that news budgets will remain tight and that statehouses are not the only beat to have suffered. Simply increasing staff, then, is often not an easy option. Some news outlets have taken steps to try to produce more with less through new kinds of collaborations. The Miami Herald and the Tampa Bay Times, for example, now share a statehouse bureau in which reporters who formerly competed with each other now coordinate coverage. In Illinois, the State Journal-Register, based in Springfield, covers the statehouse for all Illinois newspapers owned by its parent company, GateHouse Media. And in other cases, reporters work for more than one outlet. In addition, more and more state legislative offices are putting out information themselves, giving residents direct access to it—if they know where to look.

How these new collaborations and information sources impact the public is hard to assess. The changes may help fill some of the gaps created when news organizations trimmed or eliminated statehouse bureaus and may expose more people to state government issues. But they also raise questions about the level of diversity in reporting. As we found in our recent research on local television consolidation, fewer reporters following events and asking questions may well mean less diverse coverage and fewer opportunities to dig below the surface of events. As Jeff Zent, communications director for North Dakota Governor Jack Dalrymple, remarked, “The more perspectives you can get in covering a story by professional journalists, the better off the public is in being informed.”