Overview of responses

While they acknowledge that use of the internet as a tool for communications can yield both positive and negative effects, a significant majority of technology experts and stakeholders participating in the fourth Future of the Internet survey say it improves social relations and will continue to do so through 2020.

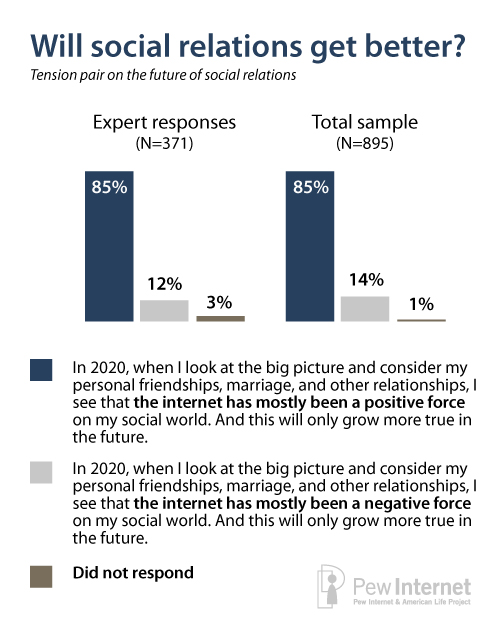

The highly engaged, diverse set of respondents to an online, opt-in survey included 895 technology stakeholders and critics. The study was fielded by the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project and Elon University’s Imagining the Internet Center.

Some 85% agreed with the statement:

- “In 2020, when I look at the big picture and consider my personal friendships, marriage and other relationships, I see that the internet has mostly been a positive force on my social world. And this will only grow more true in the future.”

Some 14% agreed with the opposite statement, which posited:

- “In 2020, when I look at the big picture and consider my personal friendships, marriage and other relationships, I see that the internet has mostly been a negative force on my social world. And this will only grow more true in the future.”

Most of people who participated in the survey were effusive in their praise of the social connectivity already being leveraged globally online. They said humans’ use of the internet’s capabilities for communication – for creating, cultivating, and continuing social relationships – is undeniable. Many enthusiastically cited their personal experiences as examples, and several noted that they had met their spouse through internet-borne interaction.

Some survey respondents noted that with the internet’s many social positives come problems. They said that both scenarios presented in the survey are likely to be accurate, and noted that tools such as email and social networks can and are being used in harmful ways. Among the negatives noted by both groups of respondents: time spent online robs time from important face-to-face relationships; the internet fosters mostly shallow relationships; the act of leveraging the internet to engage in social connection exposes private information; the internet allows people to silo themselves, limiting their exposure to new ideas; and the internet is being used to engender intolerance.

Many of the people who said the internet is a positive force noted that it “costs” people less now to communicate – some noted that it costs less money and others noted that it costs less in time spent, allowing them to cultivate many more relationships, including those with both strong and weak ties. They said “geography” is no longer an obstacle to making and maintaining connections; some noted that internet-based communications removes previously perceived constraints of “space” and not just “place.”

Some respondents observed that as use of the internet for social networks evolves there is a companion evolution in language and meaning as tech users redefine social constructs such as “privacy” and “friendship.” Other respondents suggested there will be new “categories of relationships,” a new “art of politics,” the development of some new psychological and medical syndromes that will be “variations of depression caused by the lack of meaningful quality relationships,” and a “new world society.”

A number of people said that as this all plays out people are just beginning to address the ways in which nearly “frictionless,” easy-access, global communications networks change how reputations are made, perceived, and remade.

Some confidently reported that they expect technological advances to continue to change social relations online. Among the technologies mentioned were: holographic displays and the bandwidth necessary to carry them; highly secure and trusted quantum/biometric security; powerful collaborative visualization decision-based tools; permanent, trusted, and unlimited cloud archive storehouses; open networks enabled by semantic web tools in public-domain services; and instant thought transmission in a telepathic format.

Many survey participants pointed out that while our tools are changing quickly, basic human nature seems to adjust at a slower pace.

Also in this report:

» Will social relations get better?: Main Findings

‘Tension pairs’ were designed to provoke detailed elaborations

This material was gathered in the fourth “Future of the Internet” survey conducted by the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project and Elon University’s Imagining the Internet Center. The surveys are conducted through online questionnaires to which a selected group of experts and the highly engaged Internet public have been invited to respond. The surveys present potential-future scenarios to which respondents react with their expectations based on current knowledge and attitudes. You can view detailed results from the 2004, 2006, 2008 and 2010 surveys here: https://legacy.pewresearch.org/internet/topics/Future-of-the-Internet.aspx and http://www.elon.edu/e-web/predictions/expertsurveys/default.xhtml. Expanded results are also published in the “Future of the Internet” book series published by Cambria Press.

The surveys are conducted to help accurately identify current attitudes about the potential future for networked communications and are not meant to imply any type of futures forecast.

Respondents to the Future of the Internet IV survey, fielded from Dec. 2, 2009 to Jan. 11, 2010, were asked to consider the future of the Internet-connected world between now and 2020 and the likely innovation that will occur. They were asked to assess 10 different “tension pairs” – each pair offering two different 2020 scenarios with the same overall theme and opposite outcomes – and they were asked to select the one most likely choice of two statements. The tension pairs and their alternative outcomes were constructed to reflect previous statements about the likely evolution of the Internet. They were reviewed and edited by the Pew Internet Advisory Board. Results are being released in five reports over the course of 2010.

The results that are reported in this report are responses to a tension pair that relates to the future of the Internet and social relations.

- Results to five other tension pairs – relating to the Internet and the evolution of intelligence; reading and the rendering of knowledge; identity and authentication; gadgets and applications; and the core values of the Internet – were released earlier in 2010 at the meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. They can be read at: https://legacy.pewresearch.org/internet/Reports/2010/Future-of-the-Internet-IV.aspx.

- Results from a tension pair requesting that people share their opinions on the impact of the internet on institutions were discussed at the Capital Cabal in Washington, DC, on March 31, 2010 and can be read at: https://legacy.pewresearch.org/internet/Reports/2010/Impact-of-the-Internet-on-Institutions-in-the-Future.aspx.

- Results from a tension pair assessing people’s opinions on the future of the semantic web were announced at the WWW2010 and FutureWeb conferences in Raleigh, NC, April 28, 2010 and can be read at: https://legacy.pewresearch.org/internet/Reports/2010/Semantic-Web.aspx

- Results from a tension pair probing the potential future of cloud computing were announced June 11 and can be read at: https://legacy.pewresearch.org/internet/Reports/2010/The-future-of-cloud-computing.aspx

- Final results from the Future IV survey will be released at the 2010 World Future Society conference (http://www.wfs.org/meetings.htm).

Please note that this survey is primarily aimed at eliciting focused observations on the likely impact and influence of the Internet – not on the respondents’ choices from the pairs of predictive statements. Many times when respondents “voted” for one scenario over another, they responded in their elaboration that both outcomes are likely to a degree or that an outcome not offered would be their true choice. Survey participants were informed that “it is likely you will struggle with most or all of the choices and some may be impossible to decide; we hope that will inspire you to write responses that will explain your answer and illuminate important issues.”

Experts were located in two ways. First, several thousand were identified in an extensive canvassing of scholarly, government, and business documents from the period 1990-1995 to see who had ventured predictions about the future impact of the Internet. Several hundred of them participated in the first three surveys conducted by Pew Internet and Elon University, and they were re-contacted for this survey. Second, expert participants were selected due to their positions as stakeholders in the development of the Internet.

Here are some of the respondents: Clay Shirky, Esther Dyson, Doc Searls, Nicholas Carr, Susan Crawford, David Clark, Jamais Cascio, Peter Norvig, Craig Newmark, Hal Varian, Howard Rheingold, Andreas Kluth, Jeff Jarvis, Andy Oram, Kevin Werbach, David Sifry, Dan Gillmor, Marc Rotenberg, Stowe Boyd, Andrew Nachison, Anthony Townsend, Ethan Zuckerman, Tom Wolzien, Stephen Downes, Rebecca MacKinnon, Jim Warren, Sandra Braman, Barry Wellman, Seth Finkelstein, Jerry Berman, Tiffany Shlain, and Stewart Baker.

The respondents’ remarks reflect their personal positions on the issues and are not the positions of their employers, however their leadership roles in key organizations help identify them as experts. Following is a representative list of some of the institutions at which respondents work or have affiliations: Google, Microsoft. Cisco Systems, Yahoo, Intel, IBM, Hewlett-Packard, Ericsson Research, Nokia, New York Times, O’Reilly Media, Thomson Reuters, Wired magazine, The Economist magazine, NBC, RAND Corporation, Verizon Communications, Linden Lab, Institute for the Future, British Telecom, Qwest Communications, Raytheon, Adobe, Meetup, Craigslist, Ask.com, Intuit, MITRE Corporation

Department of Defense, Department of State, Federal Communications Commission, Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Social Security Administration, General Services Administration, British OfCom, World Wide Web Consortium, National Geographic Society, Benton Foundation, Linux Foundation, Association of Internet Researchers, Internet2, Internet Society, Institute for the Future, Santa Fe Institute, Yankee Group

Harvard University, MIT, Yale University, Georgetown University, Oxford Internet Institute, Princeton University, Carnegie-Mellon University, University of Pennsylvania, University of California-Berkeley, Columbia University, University of Southern California, Cornell University, University of North Carolina, Purdue University, Duke University , Syracuse University, New York University, Northwestern University, Ohio University ,Georgia Institute of Technology, Florida State University, University of Kentucky, University of Texas, University of Maryland, University of Kansas, University of Illinois, Boston College, University of Tulsa, University of Minnesota, Arizona State, Michigan State University, University of California-Irvine, George Mason University, University of Utah, Ball State University, Baylor University, University of Massachusetts-Amherst, University of Georgia, Williams College, and University of Florida.

While many respondents are at the pinnacle of Internet leadership, some of the survey respondents are “working in the trenches” of building the web. Most of the people in this latter segment of responders came to the survey by invitation because they are on the email list of the Pew Internet & American Life Project or are otherwise known to the Project. They are not necessarily opinion leaders for their industries or well-known futurists, but it is striking how much their views were distributed in ways that paralleled those who are celebrated in the technology field.

While a wide range of opinion from experts, organizations, and interested institutions was sought, this survey should not be taken as a representative canvassing of Internet experts. By design, this survey was an “opt in,” self-selecting effort. That process does not yield a random, representative sample. The quantitative results are based on a non-random online sample of 895 Internet experts and other Internet users, recruited by email invitation, Twitter, or Facebook. Since the data are based on a non-random sample, a margin of error cannot be computed, and results are not projectable to any population other than the respondents in this sample.

Many of the respondents are Internet veterans – 50% have been using the Internet since 1992 or earlier, with 11% actively involved online since 1982 or earlier. When asked for their primary area of Internet interest, 15% of the survey participants identified themselves as research scientists; 14% as business leaders or entrepreneurs; 12% as consultants or futurists, 12% as authors, editors or journalists; 9% as technology developers or administrators; 7% as advocates or activist users; 3% as pioneers or originators; 2% as legislators, politicians or lawyers; and 25% specified their primary area of interest as “other.”

The answers these respondents gave to the questions are given in two columns. The first column covers the answers of 371 longtime experts who have regularly participated in these surveys. The second column covers the answers of all the respondents, including the 524 who were recruited by other experts or by their association with the Pew Internet Project. Interestingly, there is not great variance between the smaller and bigger pools of respondents.