Real-world examples of the scenarios in this survey

All four of the concepts discussed in the survey are based on real-life applications of algorithmic decision-making and artificial intelligence (AI):

Numerous firms now offer nontraditional credit scores that build their ratings using thousands of data points about customers’ activities and behaviors, under the premise that “all data is credit data.”

States across the country use criminal risk assessments to estimate the likelihood that someone convicted of a crime will reoffend in the future.

Several multinational companies are currently using AI-based systems during job interviews to evaluate the honesty, emotional state and overall personality of applicants.

Algorithms are all around us, utilizing massive stores of data and complex analytics to make decisions with often significant impacts on humans. They recommend books and movies for us to read and watch, surface news stories they think we might find relevant, estimate the likelihood that a tumor is cancerous and predict whether someone might be a criminal or a worthwhile credit risk. But despite the growing presence of algorithms in many aspects of daily life, a Pew Research Center survey of U.S. adults finds that the public is frequently skeptical of these tools when used in various real-life situations.

This skepticism spans several dimensions. At a broad level, 58% of Americans feel that computer programs will always reflect some level of human bias – although 40% think these programs can be designed in a way that is bias-free. And in various contexts, the public worries that these tools might violate privacy, fail to capture the nuance of complex situations, or simply put the people they are evaluating in an unfair situation. Public perceptions of algorithmic decision-making are also often highly contextual. The survey shows that otherwise similar technologies can be viewed with support or suspicion depending on the circumstances or on the tasks they are assigned to do.

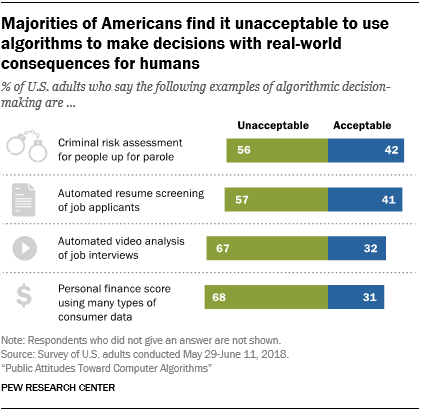

To gauge the opinions of everyday Americans on this relatively complex and technical subject, the survey presented respondents with four different scenarios in which computers make decisions by collecting and analyzing large quantities of public and private data. Each of these scenarios were based on real-world examples of algorithmic decision-making (see accompanying sidebar) and included: a personal finance score used to offer consumers deals or discounts; a criminal risk assessment of people up for parole; an automated resume screening program for job applicants; and a computer-based analysis of job interviews. The survey also included questions about the content that users are exposed to on social media platforms as a way to gauge opinions of more consumer-facing algorithms.

The following are among the major findings.

The public expresses broad concerns about the fairness and acceptability of using computers for decision-making in situations with important real-world consequences

By and large, the public views these examples of algorithmic decision-making as unfair to the people the computer-based systems are evaluating. Most notably, only around one-third of Americans think that the video job interview and personal finance score algorithms would be fair to job applicants and consumers. When asked directly whether they think the use of these algorithms is acceptable, a majority of the public says that they are not acceptable. Two-thirds of Americans (68%) find the personal finance score algorithm unacceptable, and 67% say the computer-aided video job analysis algorithm is unacceptable.

There are several themes driving concern among those who find these programs to be unacceptable. Some of the more prominent concerns mentioned in response to open-ended questions include the following:

- They violate privacy. This is the top concern of those who find the personal finance score unacceptable, mentioned by 26% of such respondents.

- They are unfair. Those who worry about the personal finance score scenario, the job interview vignette and the automated screening of job applicants often cited concerns about the fairness of those processes in expressing their worries.

- They remove the human element from important decisions. This is the top concern of those who find the automated resume screening concept unacceptable (36% mention this), and it is a prominent concern among those who are worried about the use of video job interview analysis (16%).

- Humans are complex, and these systems are incapable of capturing nuance. This is a relatively consistent theme, mentioned across several of these concepts as something about which people worry when they consider these scenarios. This concern is especially prominent among those who find the use of criminal risk scores unacceptable. Roughly half of these respondents mention concerns related to the fact that all individuals are different, or that a system such as this leaves no room for personal growth or development.

Attitudes toward algorithmic decision-making can depend heavily on context

Despite the consistencies in some of these responses, the survey also highlights the ways in which Americans’ attitudes toward algorithmic decision-making can depend heavily on the context of those decisions and the characteristics of the people who might be affected.

This context dependence is especially notable in the public’s contrasting attitudes toward the criminal risk score and personal finance score concepts. Similar shares of the population think these programs would be effective at doing the job they are supposed to do, with 54% thinking the personal finance score algorithm would do a good job at identifying people who would be good customers and 49% thinking the criminal risk score would be effective at identifying people who are deserving of parole. But a larger share of Americans think the criminal risk score would be fair to those it is analyzing. Half (50%) think this type of algorithm would be fair to people who are up for parole, but just 32% think the personal finance score concept would be fair to consumers.

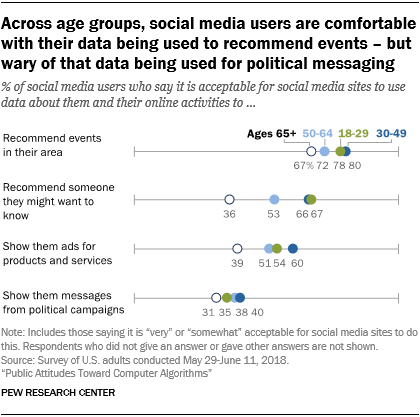

When it comes to the algorithms that underpin the social media environment, users’ comfort level with sharing their personal information also depends heavily on how and why their data are being used. A 75% majority of social media users say they would be comfortable sharing their data with those sites if it were used to recommend events they might like to attend. But that share falls to just 37% if their data are being used to deliver messages from political campaigns.

In other instances, different types of users offer divergent views about the collection and use of their personal data. For instance, about two-thirds of social media users younger than 50 find it acceptable for social media platforms to use their personal data to recommend connecting with people they might want to know. But that view is shared by fewer than half of users ages 65 and older.

Social media users are exposed to a mix of positive and negative content on these sites

Algorithms shape the modern social media landscape in profound and ubiquitous ways. By determining the specific types of content that might be most appealing to any individual user based on his or her behaviors, they influence the media diets of millions of Americans. This has led to concerns that these sites are steering huge numbers of people toward content that is “engaging” simply because it makes them angry, inflames their emotions or otherwise serves as intellectual junk food.

On this front, the survey provides ample evidence that social media users are regularly exposed to potentially problematic or troubling content on these sites. Notably, 71% of social media users say they ever see content there that makes them angry – with 25% saying they see this sort of content frequently. By the same token, roughly six-in-ten users say they frequently encounter posts that are overly exaggerated (58%) or posts where people are making accusations or starting arguments without waiting until they have all the facts (59%).

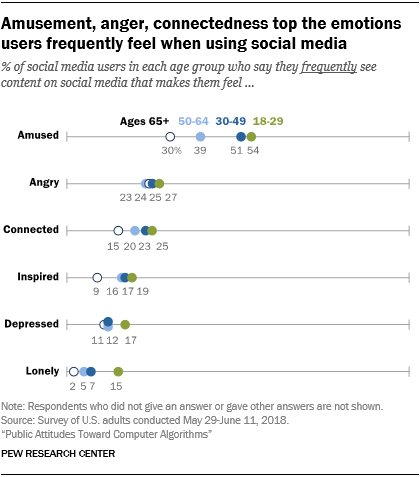

But as is often true of users’ experiences on social media more broadly, these negative encounters are accompanied by more positive interactions. Although 25% of these users say they frequently encounter content that makes them feel angry, a comparable share (21%) says they frequently encounter content that makes them feel connected to others. And an even larger share (44%) reports frequently seeing content that makes them amused.

Similarly, social media users tend to be exposed to a mix of positive and negative behaviors from other users on these sites. Around half of users (54%) say they see an equal mix of people being mean or bullying and people being kind and supportive. The remaining users are split between those who see more meanness (21%) and kindness (24%) on these sites. And a majority of users (63%) say they see an equal mix of people trying to be deceptive and people trying to point out inaccurate information – with the remainder being evenly split between those who see more people spreading inaccuracies (18%) and more people trying to correct that behavior (17%).

Similarly, social media users tend to be exposed to a mix of positive and negative behaviors from other users on these sites. Around half of users (54%) say they see an equal mix of people being mean or bullying and people being kind and supportive. The remaining users are split between those who see more meanness (21%) and kindness (24%) on these sites. And a majority of users (63%) say they see an equal mix of people trying to be deceptive and people trying to point out inaccurate information – with the remainder being evenly split between those who see more people spreading inaccuracies (18%) and more people trying to correct that behavior (17%).

Other key findings from this survey of 4,594 U.S. adults conducted May 29-June 11, 2018, include:

- Public attitudes toward algorithmic decision-making can vary by factors related to race and ethnicity. Just 25% of whites think the personal finance score concept would be fair to consumers, but that share rises to 45% among blacks. By the same token, 61% of blacks think the criminal risk score concept is not fair to people up for parole, but that share falls to 49% among whites.

- Roughly three-quarters of the public (74%) thinks the content people post on social media is not reflective of how society more broadly feels about important issues – although 25% think that social media does paint an accurate portrait of society.

- Younger adults are twice as likely to say they frequently see content on social media that makes them feel amused (54%) as they are content that makes them feel angry (27%). But users ages 65 and older encounter these two types of content with more comparable frequency. The survey finds that 30% of older users frequently see content on social media that makes them feel amused, while 24% frequently see content that makes them feel angry.