To borrow an expression from the technology industry, harassment is now a “feature” of life online for many Americans. In its milder forms, it creates a layer of negativity that people must sift through as they navigate their daily routines online. At its most severe, it can compromise users’ privacy, force them to choose when and where to participate online, or even pose a threat to their physical safety.

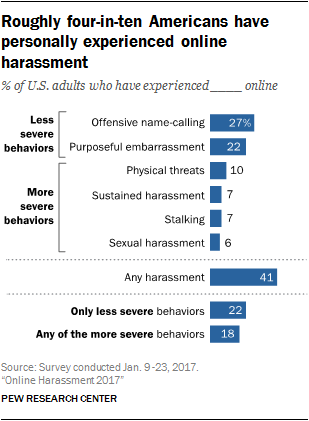

A new, nationally representative Pew Research Center survey of 4,248 U.S. adults finds that 41% of Americans have been personally subjected to harassing behavior online, and an even larger share (66%) has witnessed these behaviors directed at others. In some cases, these experiences are limited to behaviors that can be ignored or shrugged off as a nuisance of online life, such as offensive name-calling or efforts to embarrass someone. But nearly one-in-five Americans (18%) have been subjected to particularly severe forms of harassment online, such as physical threats, harassment over a sustained period, sexual harassment or stalking.

A new, nationally representative Pew Research Center survey of 4,248 U.S. adults finds that 41% of Americans have been personally subjected to harassing behavior online, and an even larger share (66%) has witnessed these behaviors directed at others. In some cases, these experiences are limited to behaviors that can be ignored or shrugged off as a nuisance of online life, such as offensive name-calling or efforts to embarrass someone. But nearly one-in-five Americans (18%) have been subjected to particularly severe forms of harassment online, such as physical threats, harassment over a sustained period, sexual harassment or stalking.

Social media platforms are an especially fertile ground for online harassment, but these behaviors occur in a wide range of online venues. Frequently these behaviors target a personal or physical characteristic: 14% of Americans say they have been harassed online specifically because of their politics, while roughly one-in-ten have been targeted due to their physical appearance (9%), race or ethnicity (8%) or gender (8%). And although most people believe harassment is often facilitated by the anonymity that the internet provides, these experiences can involve acquaintances, friends or even family members.

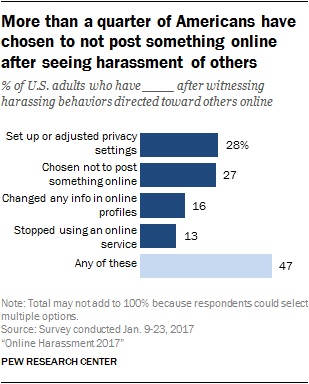

For those who experience online harassment directly, these encounters can have profound real-world consequences, ranging from mental or emotional stress to reputational damage or even fear for one’s personal safety. At the same time, harassment does not have to be experienced directly to leave an impact. Around one-quarter of Americans (27%) say they have decided not to post something online after witnessing the harassment of others, while more than one-in-ten (13%) say they have stopped using an online service after witnessing other users engage in harassing behaviors. At the same time, some bystanders to online harassment take an active role in response: Three-in-ten Americans (30%) say they have intervened in some way after witnessing abusive behavior directed toward others online.

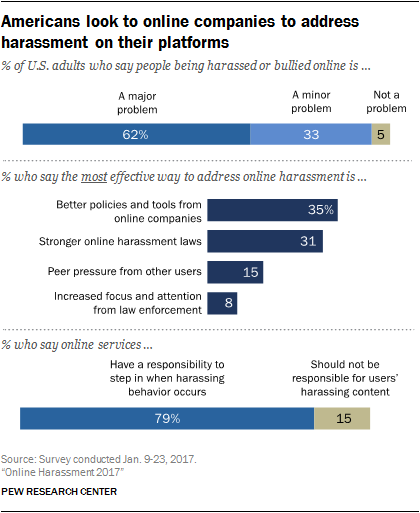

Yet even as harassment permeates many users’ online interactions, the public offers conflicting views on how best to address this issue. A majority of Americans (62%) view online harassment as a major problem, and nearly eight-in-ten Americans (79%) say online services have a duty to step in when harassment occurs on their platforms. On the other hand, they are highly divided on how to balance concerns over safety with the desire to encourage free and open speech – as well as whether offensive content online is taken too seriously or dismissed too easily.

Four-in-ten U.S. adults have personally experienced harassing or abusive behavior online; 18% have been the target of severe behaviors such as physical threats, sexual harassment

Around four-in-ten Americans (41%) have been personally subjected to at least one type of online harassment – which this report defines as offensive name-calling online (27% of Americans say this has happened to them), intentional efforts to embarrass someone (22%), physical threats (10%), stalking (7%), harassment over a sustained period of time (7%) or sexual harassment (6%). This 41% total includes 18% of U.S. adults who say they have experienced particularly severe forms of harassment (which includes stalking, physical threats, sexual harassment or harassment over a sustained period of time).

The share of Americans who have been subjected to harassing behavior online has increased modestly since Pew Research Center last conducted a survey on this topic in 2014. At that time, 35% of all adults had experienced some form of online harassment.1

A wide cross-section of Americans have experienced these behaviors in one way or another, but harassment is especially prevalent in the lives of younger adults. Fully 67% of 18- to 29-year-olds have been the target of any of these behaviors, including 41% who have experienced some type of severe harassment online. At the same time, harassment is increasingly a fact of online life for Americans in other age groups. Nearly half of 30- to 49-year olds (49%) have personally experienced any form of online harassment (an increase of 10 percentage points since 2014), as have 22% of Americans ages 50 and older (an increase of 5 points over the same time period).

Harassment is often focused on personal or physical characteristics; political views, gender, physical appearance and race are among the most common

Personal or physical traits are easy fodder for online harassment, particularly political views. Some 14% of U.S. adults say they have ever been harassed online specifically because of their political views, while roughly one-in-ten have been targeted due to their physical appearance (9%), race (8%) or gender (8%).2 Somewhat smaller shares have been targeted for other reasons, such as their religion (5%) or sexual orientation (3%).

Certain groups are more likely than others to experience this sort of trait-based harassment. For instance, one-in-four blacks say they have been targeted with harassment online because of their race or ethnicity, as have one-in-ten Hispanics. The share among whites is lower (3%). Similarly, women are about twice as likely as men to say they have been targeted as a result of their gender (11% vs. 5%). Men, however, are around twice as likely as women to say they have experienced harassment online as a result of their political views (19% vs. 10%). Similar shares of Democrats and Republicans say they have been harassed online as a result of their political leanings.

Americans are widely aware of the issue of online harassment, and 62% consider it a major problem; online companies are seen as key actors in addressing online harassment

Public awareness of online harassment is high: 94% of U.S. adults have some degree of familiarity with this issue, and one-third have heard a lot about it. Overall, 62% of the public considers online harassment to be a major problem, while just 5% do not consider it to be a problem at all.

Public awareness of online harassment is high: 94% of U.S. adults have some degree of familiarity with this issue, and one-third have heard a lot about it. Overall, 62% of the public considers online harassment to be a major problem, while just 5% do not consider it to be a problem at all.

When asked who should be responsible for policing or preventing abuse online, Americans assign responsibility to a variety of actors – most prominently, online companies and platforms. Roughly eight-in-ten Americans (79%) feel that online services have a responsibility to step in when harassing behavior occurs on their platforms, while just 15% say that these services should not be held responsible for the behavior and content of its users. Meanwhile, 64% say online platforms should play a major role in addressing online harassment, and 35% believe that better policies and tools from these companies are the most effective way to address online harassment.

At the same time, the public recognizes its own role in curbing online harassment. Fully 60% of Americans say that bystanders who witness harassing behavior online should play a major role in addressing this issue, and 15% feel that peer pressure from others is the single-most effective way to address online harassment. They also see a significant role for law enforcement in dealing with online abuse: 49% think law enforcement should play a major role in addressing online harassment, and 31% say stronger laws are the single-most effective way to address this issue. Simultaneously, a sizable proportion of Americans (43%) say that law enforcement currently does not take online harassment incidents seriously enough.

Americans are divided on the issues of free speech and political correctness that underlie the online harassment debate

Despite this broad concern over online harassment, Americans are more divided over how to balance protecting free expression online and preventing behavior that crosses into abuse. When asked how they would prioritize these competing interests, 45% of Americans say it is more important to let people speak their minds freely online; a slightly larger share (53%) feels that it is more important for people to feel welcome and safe online.

Americans are also relatively divided on just how seriously offensive content online should be treated. Some 43% of Americans say that offensive speech online is too often excused as not being a big deal, but a larger share (56%) feel that many people take offensive content online too seriously. The latter view is prominent among men in general, and among young men in particular: 73% of 18- to 29-year-old men feel that many people take offensive online content too seriously.

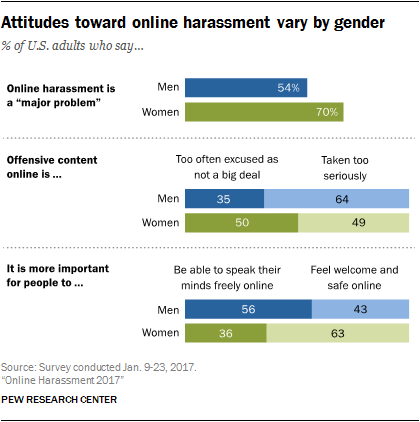

Experiences and attitudes toward online harassment vary significantly by gender

Men and women experience and respond to online harassment in different ways. Overall, men are somewhat more likely to experience any form of harassing behavior online: 44% of men and 37% of women have experienced at least one of the six behaviors this study uses to define online harassment. In terms of specific experiences, men (30%) are modestly more likely than women (23%) to have been called offensive names online or to have received physical threats (12% vs. 8%).

Men and women experience and respond to online harassment in different ways. Overall, men are somewhat more likely to experience any form of harassing behavior online: 44% of men and 37% of women have experienced at least one of the six behaviors this study uses to define online harassment. In terms of specific experiences, men (30%) are modestly more likely than women (23%) to have been called offensive names online or to have received physical threats (12% vs. 8%).

By contrast, women – and especially young women – encounter sexualized forms of abuse at much higher rates than men. Some 21% of women ages 18 to 29 report being sexually harassed online, a figure that is more than double the share among men in the same age group (9%). In addition, roughly half (53%) of young women ages 18 to 29 say that someone has sent them explicit images they did not ask for. For many women, online harassment leaves a strong impression: 35% of women who have experienced any type of online harassment describe their most recent incident as either extremely or very upsetting, about twice the share among men (16%).

More broadly, men and women differ sharply in their attitudes toward the relative importance of online harassment as an issue. For instance, women (63%) are much more likely than men (43%) to say people should be able to feel welcome and safe in online spaces, while men are much more likely than women to say that people should be able to speak their minds freely online (56% of men vs. 36% of women). Similarly, half of women say offensive content online is too often excused as not being a big deal, whereas 64% of men – and 73% of young men ages 18 to 29 – say that many people take offensive content online too seriously. Further, 70% of women – and 83% of young women ages 18 to 29 – view online harassment as a major problem, while 54% of men and 55% of young men share this concern.

Attitudes toward different policies to prevent online harassment also differ somewhat by gender. Men are more likely than women to believe that improved policies and tools from online companies are the most effective approach to addressing online harassment (39% vs. 31%). Meanwhile, women are more likely to say that stronger laws against online harassment are the most effective approach (36% vs. 24%), and they are also more likely to feel that law enforcement currently does not take online harassment incidents seriously enough (46% vs. 39%).

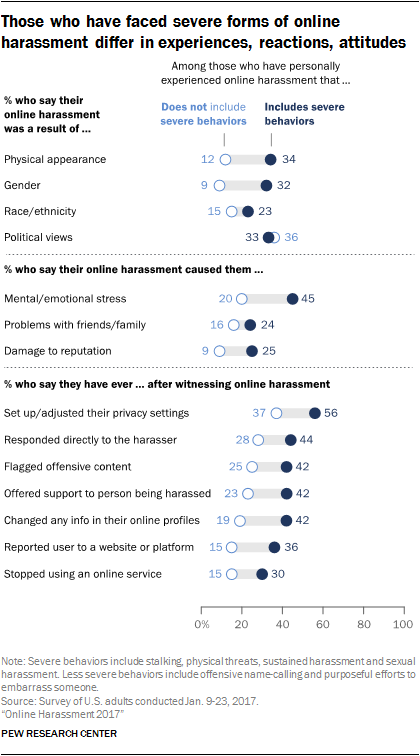

Harassment exists on a spectrum of severity: Those who have experienced severe forms of online harassment differ sharply in their reactions and attitudes

Many online harassment experiences begin and end with offensive name-calling or efforts to be embarrassed, behaviors that are often easy enough to shrug off as a nuisance of life online. But the 18% of Americans who have experienced more severe forms of harassment – such as physical threats, sustained harassment, sexual harassment and/or stalking – differ dramatically in their personal reactions and broader attitudes toward online harassment.

Many online harassment experiences begin and end with offensive name-calling or efforts to be embarrassed, behaviors that are often easy enough to shrug off as a nuisance of life online. But the 18% of Americans who have experienced more severe forms of harassment – such as physical threats, sustained harassment, sexual harassment and/or stalking – differ dramatically in their personal reactions and broader attitudes toward online harassment.

In the immediate aftermath of an online harassment incident, those with severe experiences are more likely to report a variety of consequences, ranging from problems with their friends and family to damage to their reputation. They are more likely to say that a personal characteristic – like their gender or race/ethnicity – was ever the root of their harassment, and to respond to their harassment by deleting their profile or changing their username, ceasing to attend certain offline places, or contacting law enforcement.

Those with severe harassment experiences are also more likely to report a strong reaction to their abuse. More than four-in-ten (44%) say their most recent experience caused mental or emotional stress, 44% say they found the incident “extremely” or “very” upsetting, and 29% felt their physical safety (or the physical safety of those close to them) was at risk. Those who have ever been targeted with severe harassment behaviors are also more likely to feel high levels of anxiety when they witness others being harassed online, more likely to actively protect themselves and their online identities in response to online harassment, and more likely to seek support from a number of sources.

Perhaps most striking, those with severe harassment experiences show a high tendency to intervene when they see others going through similar situations. Almost two-thirds (63%) of those who have ever been targeted with severe behaviors say they have taken action to intervene when they saw someone else harassed online, compared with 48% whose harassment does not include severe behaviors.

At the same time, the attitudes each group has toward the underlying issues of online harassment are closely aligned. For instance, about six-in-ten U.S. adults (62%) say they consider online harassment to be a major problem, regardless of the severity of their personal experiences with online abuse. On issues such as the relative balance between free speech and safety online, or whether online harassment is taken too seriously or dismissed too easily, there are no differences based on the severity of one’s own experiences with online harassment. Further, majorities of both groups agree that online services should play a major role in addressing harassment, and similar shares look to stronger laws and better policies and tools from companies as ways to effectively curb harassment.

Online harassment is often subjective – even to those experiencing the worst of it

Although this survey defines online harassment using six specific behaviors, the findings also indicate that what people actually consider to be “online harassment” is highly contextual and varies from person to person. Among the 41% of U.S. adults who have experienced one or more of the six behaviors that this survey uses to define online harassment, 36% feel their most recent experience does indeed qualify as “online harassment.” At the same time, 37% say they do not think of their experience as online harassment, and another 27% are unsure if they were victims of online harassment or not. Strikingly, 28% of those whose most recent encounter involved severe types of abusive behavior – such as stalking, sexual harassment, sustained harassment or physical threats – do not think of their own experience as constituting “online harassment.” Meanwhile, 32% of those who have only encountered “mild” behaviors such as name-calling or embarrassment do consider their most recent experience to be online harassment.

Two-thirds of Americans have witnessed abusive or harassing behavior toward others online

Beyond their own personal experiences, a substantial majority of Americans (66%) say they have witnessed some type of harassing behavior directed toward others online, with 39% indicating they have seen others targeted with severe behaviors such as stalking, physical threats, sustained harassment or sexual harassment. As was true of the harassment Americans experience personally, younger adults are especially likely to witness harassing behavior toward others online. Fully 86% of 18- to 29-year-olds say they have witnessed at least one of these six behaviors, and 62% have seen others targeted for severe forms of abuse.

Beyond their own personal experiences, a substantial majority of Americans (66%) say they have witnessed some type of harassing behavior directed toward others online, with 39% indicating they have seen others targeted with severe behaviors such as stalking, physical threats, sustained harassment or sexual harassment. As was true of the harassment Americans experience personally, younger adults are especially likely to witness harassing behavior toward others online. Fully 86% of 18- to 29-year-olds say they have witnessed at least one of these six behaviors, and 62% have seen others targeted for severe forms of abuse.

Exposure to these behaviors can have pronounced impacts on those witnessing them. In some cases, this involves people taking basic precautions to protect themselves: 28% of Americans say that observing the harassment of others has influenced them to set up or adjust their own privacy settings. But in other cases, widespread abusive behavior can have a more pronounced chilling effect: 27% of U.S. adults say they have refrained from posting something online after witnessing the harassment of others, and 13% of the population has elected to stop using an online service due to the harassment of others they observe. Additionally, 8% of all adults (and 12% of 18- to 29-year-olds) say they have been very anxious after witnessing harassment of others online.

Anonymity is seen as a facilitating factor in encouraging the spread of harassment online

Users increasingly see the internet as a place that facilitates anonymity. Some 86% of online adults feel that the internet allows people to be more anonymous than is true offline. This represents a notable increase from the 62% who said this in Pew Research Center’s 2014 survey. And this ability to be anonymous online is often tied to the issue of online harassment. Roughly half of those who have been harassed online (54%) say their most recent incident involved a stranger and/or someone whose real identity they did not know. More broadly, 89% of Americans say the ability to post anonymously online enables people to be cruel to or harass one another.

Among other findings:

- About one-quarter of all adults (26%) have had untrue information about them posted online, most commonly about their character or reputation (17%). Half (49%) of those who had untrue information posted about them tried to get the inaccurate claims removed or corrected, and around one-in-ten Americans (9%) say they have experienced mental or emotional stress because of something untrue posted about them online.

- Large majorities of internet users have heard about hacking (95%) and trolling (86%), and 18% each have personally been hacked or trolled. Doxing – that is, posting someone’s personal information online without their consent – and swatting – which refers to calling in a fake emergency to the police – are recognized by smaller shares of the online population (73% and 55%, respectively).

Shareable quotes from Americans on online harassment

Shareable quotes from Americans on online harassment