Respondents’ thoughts

The wide range of variability in the tone of the answers to this question can be represented by the following two opposing statements, made by anonymous respondents who filed their answers at the same time on the same day:

- “The development of the Internet as a complex adaptive system will continue to evolve, and attempts to control information will be thwarted by complexity.”

- “All governments will want to have a kill switch just in case.”

At the time this question was posed to the expert respondents, a series of uprisings and protests was playing out in Arab countries, the consequences of the social media-abetted “Green Revolution” in Iran were being debated, there were regular media reports about the struggles of Chinese citizens to learn and share, and Russian protesters were routinely demonstrating against the acts of the Putin regime. In the same period during the summer of 2011, the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit Authority cut off mobile service for three hours in some rapid transit stations in order to hinder protestors who allegedly planned to disrupt evening commuting service.8

After riots in Great Britain in August 2011, Prime Minister David Cameron wondered if the Twitter and Facebook accounts of rioters should be shut down in the midst of civil strife. “Everyone watching these horrific actions will be struck by how they were organised via social media. Free flow of information can be used for good. But it can also be used for ill,” Cameron said.9 “And when people are using social media for violence we need to stop them. So we are working with the police, the intelligence services and industry to look at whether it would be right to stop people communicating via these websites and services when we know they are plotting violence, disorder and criminality. I have also asked the police if they need any other new powers.”

At the same time these events were unfolding, a number of technologically oriented organizations continued their discussions about the core “values” that should be built into technology’s architecture. Those groups included the Internet Society10 and the United Nation’s Internet Governance Forum.11 Other international and national groups such as THE OECD12, Council of Europe13, and Brazil14 have been debating for several years what principles should govern the Internet.

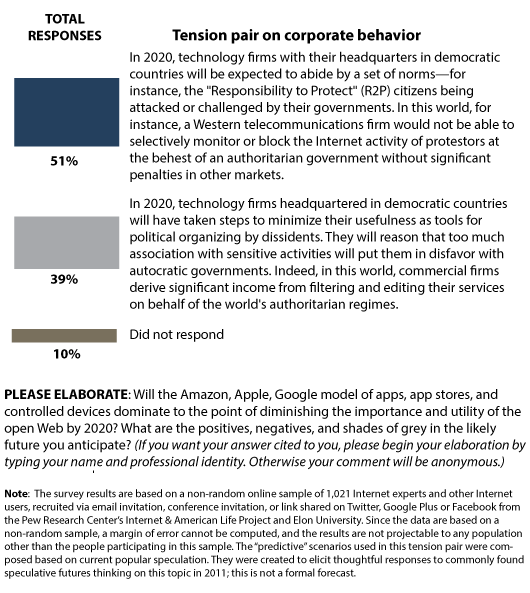

Thus, these crackdowns by governments against protesters and dissidents, the debates about tech companies’ roles in those crackdowns, and the ongoing global conversation about the principles of the Internet prompted us to pose these two scenarios about how things might unfold by the year 2020.

After being asked to choose one of the two 2020 scenarios presented in this survey question, respondents were also asked, “When it comes to the behavior and practices of global tech firms and political, social, and economic movements, how will firms respond? Explain your choice and share your view of this tension pair’s implications for the future. What are the positives, negatives, and shades of grey in the likely future you anticipate?”

Following is a selection from the hundreds of written responses survey participants shared when answering this question. About half of the expert survey respondents elected to remain anonymous, not taking credit for their remarks. Because the expertise of respondents is an important element of their participation in the conversation, the formal report primarily includes the comments of those who took credit for what they said. The full set of expert responses to the Future of the Internet V survey, anonymous and not, can be found online at http://www.elon.edu/e-web/predictions/expertsurveys/2012survey/

future_corporate_responsibility_2020.xhtml. The selected statements that follow here are grouped under headings that indicate some of the major themes emerging from the overall responses. The varied and conflicting headings indicate the wide range of opinions found in respondents’ reflective replies.

Consumers will respond badly if corporations do not work for the greater good; Internet builders will continue to push for free flows of information.

Some respondents believe that the trends both in market behavior by conscientious citizens and in technology development will generally move in directions that help protestors and dissidents.

Mark Watson, senior engineer for Netflix and a leading participant in various technology groups related to the Internet (IETF, W3C), wrote: “Recent events and the perceived role of social media mark a watershed, which will prevent the second scenario coming about: firms that err too much on conceding to autocratic governments will be penalized by consumers (though I doubt by government as described in the first point).”

Rajnesh Singh, regional director, Asia, for the Internet Society, added: “Firms worldwide are very quickly learning the power the Internet places in the hands of the consumer, particularly when it comes to advocacy and cause-based action. I think it is this—consumers being able to organise across borders—more than anything else that will drive firms to be more responsible in their actions wherever they operate. Power to the people by the people in the hands of people will have much greater meaning across all spheres—including trade and commerce.”

Mack Reed, principal, Factoid Labs, a consultancy on content, social engineering, design, and business analysis, supported that notion: “In general, people dislike having the government and large corporations controlling their lives, and will become increasingly sensitized to such intrusions.”

Jeffrey Alexander, senior policy analyst at the Center for Science, Technology & Economic Development at SRI International, explained, “The norms and culture of the past Internet will be more of an influence on the behavior of Internet infrastructure firms than any new set of expectations or norms. Far beyond platitudes like ‘don’t be evil,’ the engineers who develop new technologies will have both the inclination and incentive to design them to be resistant to central control and to undermine autocratic behaviors. Also, dissidents are more technology-savvy than dictatorships, and they will be able to repurpose digital technologies to serve their purposes more effectively than central governments will be able to use them for surveillance and suppression. The more pertinent danger is when corporations themselves become centers of power, and they shape technologies to serve their own interests rather than protecting consumer rights. This will be a trend that will be difficult to combat at the individual or governmental level, as the interests of the engineers and management may be more in alignment. This may enable firms to distort technological evolution to favor their interests over those of consumers.”

Jonathan Grudin, principal researcher at Microsoft, wrote: “Have you been reading the papers? In the United Kingdom and parts of the United States, governments are seriously examining or enacting control of social media locally. I don’t actually think the big companies in ‘democratic countries’ will care much about what happens in Syria, and they will try to tread carefully around China. I remain fairly optimistic, though, that ‘technology firms’ won’t be in complete control here, or that some of them will succeed in remaining largely conduits, and that firms that try to control content in response to government intervention will risk being abandoned in droves, and thus forced to stick to a reasonable path. We will see.”

William L Schrader, independent consultant, founder of PSINet in 1989— the largest independent publicly traded global ISP during the 1990s, and lecturer on the future impact of the Internet, wrote in personal terms as a consumer and in analytical terms as an observer of political legitimacy: “The market forces will determine which of these outcomes is seen. I, for one, would not willingly buy services from a US-HQ firm that refused to keep secret the identities of demonstrators in a rioting state (whether Iraq, Egypt, Syria, Libya, or even Canada and especially the United States). Of course, all regimes, including those in the United States, have at times used illegal techniques to enforce the powerful will of those in command. In those instances we, who are observant, see what the technology company leadership is made of and that is where my loyalties will follow. The Internet is a leveling tool for the powerful and for the weak. At the same time, mediocracy [mediocre democracy] is not the outcome—since the powerful lose power and the weak can gain it if and only if they learn how to communicate and are willing to share openly and honestly. Once anyone loses the faith of the people, the Internet will provide others the means to drain power from them. In a single phrase, the Internet is the last defense for true democracy.”

A large portion of respondents to this survey question did not sign their responses. Some of their answers were relatively optimistic about the scenario in the survey where companies are compelled not to help those who treat workers and dissidents harshly. Here is a sampling of anonymous responses that went in this direction:

— “As we can see from backlashes against Apple (Foxconn suicides), and massive support for Google in leaving China because of its censorship demands, most multinational IT companies will opt for keeping their customers happy in the advanced countries—if only for economic reasons (those customers have far more money, and thus influence).”

— “Activism on the part of various groups, including Anonymous, will help to steer corporate citizens into doing the right thing. Given the division within the US Congress, I do not expect the legislative branch to take the lead on this issue.”

— “Abiding by a set of norms is always a hope rather than a given. Yet the decision by the UK government not to shut down social media during civil unrest is a hopeful sign. BART’s planned shutdown of cell phones drew protest. Just as civil and human rights have been taken up by governments in the past, so, too, does access to communications tools become a civil right and a better for debate in governments worldwide.”

— “Technology firms will be goaded into abiding by sets of norms. This will occur on a case-by-case basis, with no full-scale adoption of a norm of morality.”

— “‘Don’t be evil’ [Google’s corporate slogan] will become ‘don’t be stupid’ and there’s a difference. People will know more about the values and actions of the corporations that serve them and will be making consumer choices at times based on that information. Some companies will welcome this—they’ll cater to one consumer group’s value set (for example, Christian right or environmentalists) while others seeking a mass audience will behave as neutrally as possible in all spheres to avoid upsetting a portion of the population. Pan-national companies will have a local face and might perform differently based on the market.”

— “By 2020, technology firms will function much like they do today, but possibly with more social-oriented ethics in place. Governments will have more accountability to activist organizations and citizenship groups because of the ‘no one can hide forever’ nature of the Internet. This will increase the need for ethical behavior among technology providers. Technology firms may have more of an obligation to monitor their own developments to be corporate citizens of society—‘first, do no harm.’”

People will find ways to route around bottlenecks and/or innovate new systems that foster rights and freedom.

A number of respondents were less focused on specific corporations and their behaviors than they were on the larger forces driving the structure of digital networks. They think people have a decent chance to hack their way around surveillance problems or find alternative tools for sharing information with fellow travelers.

Mike Liebhold, senior researcher and distinguished fellow at The Institute for the Future, was among the most forceful proponents of this view: “Large technology firms will inevitably cave in to governments’ pressure to surveil and control citizens’ activities. The good news is that grass roots, open-source capabilities will grow increasingly useful for people to work around government penetration of our digital infrastructures.”

Jeffrey Alexander, senior science and technology policy analyst at theCenter for Science, Technology & Economic Development, SRI International, echoed the thought: “The norms and culture of the past Internet will be more of an influence on the behavior of Internet infrastructure firms than any new set of expectations or norms. Far beyond platitudes like ‘don’t be evil,’ the engineers who develop new technologies will have both the inclination and incentive to design them to be resistant to central control and to undermine autocratic behaviors. Also, dissidents are more technology-savvy than dictatorships, and they will be able to repurpose digital technologies to serve their purposes more effectively than central governments will be able to use them for surveillance and suppression. The more pertinent danger is when corporations themselves become centers of power, and they shape technologies to serve their own interests rather than protecting consumer rights. This will be a trend that will be difficult to combat at the individual or governmental level, as the interests of the engineers and management may be more in alignment. This may enable firms to distort technological evolution to favor their interests over those of consumers.”

Paul Jones, clinical associate professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, expressed more of a hope than a prophesy that dissidents will find pathways to help themselves: “We are now at the time of greatest use of mobile technologies for social change. But this is largely because there are so many options for communications that it is difficult to block them all. Radio in Serbia, texting in the Philippines, Twitter in Egypt, colored shirts in Ukraine, phone trees, USB exchange, etc. The problem of blocking by a government or its agents will be continuing. The resistance to a monoculture of communications is the only way to confront that undemocratic impulse. Businesses, although considered ‘persons,’ are not moral.”

Mary Hodder, founder of Dabble Wellness Mobile and a technologist and product developer and chair of the Personal Data Ecosystem Consortium spoke up for how distributed systems can provide help to the beleaguered: “The key will be to design communication tech that is not client/server or cow/calf, but instead dispersed and unable to be controlled. If we do that, then we have a chance at getting a scenario that is more like number one.”

Jerry Michalski, guide and founder of Relationship Economy Expedition (REXpedition) and founder and president of Sociate, chose not to vest hope in corporations but in those who can act outside their control: “Given how the Obama administration, which one would expect to take a citizen-friendly approach to national security, has kept in place the warrantless wiretapping, extraordinary rendition, no habeas corpus, and other extravagant incursions into civil liberties that the Bush administration undertook, I think few organizations will resist the pull to collaborate with governments. We’re all watching what Google and Microsoft do in China, while other makers of communications gear build back doors into their systems so they can close sales to other regimes. The sale of communications gear has become like the arms industries, and it’s unclear if there are any feedback loops or Wikileaks-like institutions that are taking on this problem. So it may be up to activists of many stripes to build a parallel Internet that is truly free of those players and those forces. The odds of this happening are vanishingly slim.”

Ted M. Coopman, lecturer in the Department of Communication Studies at San Jose State University, also noted the special role of hackers: “The lessons had in China and other nations illustrated to technology firms that the cost of compliance is too high. Autocratic governments by their nature are untrustworthy and cannot be negotiated with because they can easily simply change their minds. If information technology companies capitulate, it is too easy to lose on both ends. Unlike extractive industries, IT firms can arise from anywhere and be everywhere. What we will see is an industry arise with the expressed purpose of aiding regimes and hacking IT companies to get the information they need to disrupt dissent. Let the Net wars begin.”

Anonymous respondents, too, gave voice to these hopes:

— “Should a system/technology change to remove functionality that users have leveraged in the past for social or political purposes, another company in the tech landscape will pop up to fill/exploit that void and there will be a mass migration. There will always be a new Twitter, Facebook, or Tumblr should the old one turn into a dud.”

— “Open-source communications will expand and there will be less and less ability to monitor or block. There will be more energy spent on observing and coding for analysis. The Web is too free a space to control, but activity can be tracked.”

It’s not easy to do right by everyone; corporate leaders prefer to avoid politics; when possible, they do their best to suit humanitarian goals.

Some of the answers focused on the balancing act that corporations must perform as they try to sell goods and services, follow the rules of governments and norms of local cultures, and burnish their brand reputations. Each of these imperatives can push firms in a different direction.

Lee W. McKnight, professor of entrepreneurship and innovation atSyracuse University and founder of Wireless Grids, wrote: “For businesses worldwide and their shareholders it’s about the money, but being closely associated with suppressing legitimate protest movements through use of a firm’s technology will be bad for business.”

Jeff Eisenach, managing director and principal ofNavigant Economics and formerly a senior policy expert with the U.S. Federal Trade Commission, added: “Firms will continue to resolve these issues on a case-by-case basis, usually out of sight of First Amendment advocates.” Anonymous respondent: “I believe the founders of these companies prefer that information be open.”

Jim Jansen, associate professor in the College of Information Sciences and Technology at Penn State University and board member of eight international technology journals, reported: “Having done some work in this area, [I see that] companies will walk a fine line between not aiding criminal activity and not trampling on rights. Most companies will take actions—for instance not storing data beyond a certain point—in order to limit their legal liability.”

Again, a number of anonymous respondents offered important insights. These were some of their responses:

— “I remain hopeful that the idea of freedom—and protecting freedom —will somehow reside in corporations with headquarters in democratic countries, despite pressure to focus on profits from stockholders in democratic countries. So far the public noise level is high and against blocking protesters’ Internet activity as a result of public exposures—with eyewitness photos and movies—by media companies and citizens alike of injustices and violence. Just as authoritarian regimes and the tyrants associated with them can be more readily exposed to many people through modern telecommunications technologies, so also can offending telecommunications firms be exposed to more people. I remain hopeful that technology firms will abide by a set of norms that support freedom because it’s the right thing to do, and people support them in their efforts on behalf of freedom.”

— “It is not the role of technology firms to decide when to protect citizens. They develop technology; they do not play politics. There should not be rules that will affect their ability to innovate and develop and not get involved in politics. Whenever private firms get more involved in politics, they add to corruption rather than limit it.”

Corporate leaders use all of the angles to gain optimal business advantage. Sometimes they follow pro-democratic norms; other times they play by authoritarian rules. They can also set up subsidiaries in messy situations.

A more hard-eyed analysis came from respondents who argued that corporate behavior was more guided by opportunism than altruism.

John Smart, professor of emerging technologies at the University of Advancing Technology and president and founder of the Acceleration Studies Foundation, wrote: “Neither broad-scale R2P nor significant work for authoritarian regimes will occur. Corporations are effective at being both opportunistic and agnostic on these issues, and there’s no win for them to be committed to either outcome. Only when we have a real valuecosm platform on the Web (http://bit.ly/GIvLn2), in 2030 and beyond, will individual citizens within democracies have enough artificial intelligence guiding their purchasing and voting decisions to begin to seriously enforce R2P and other corporate social responsibility activities in significant ways. In the meantime, corporations will do PR spin around these issues but will effectively be able to avoid being either an advocate of or a policer of the common citizen.”

danah boyd, senior researcher with professional affiliations and work based at Microsoft Research summed up this point of view: “Most companies will publicly state that they are doing everything possible to protect citizens while making countless concessions and political decisions that will end up harming citizens. They will work with some governments and not with others. They will reveal the political nature of these processes and make decisions that will shape how they are perceived by their core consumers. They will be constantly called out for their hypocrisies and working to weather political storms by upset customers. But they will publicly present the values that their customers want to hear and their customers mostly want to hear that they’re doing everything possible to protect the good guys.”

Ebenezer Baldwin Bowles, owner and managing editor of corndancer.com, committed to the non-commercial roots of the Internet and World Wide Web, maintained: “Technology firms may be expected to abide by a set of norms, but the expectations are for public consumption only. The links between elected representatives of so-called democratic countries and the corporate powers that corrupt them absolutely are so tightly woven that they render integrity and ethics meaningless. By 2020 technology firms will be functionally dependent on regulatory protections afforded by insider legislation and increasingly fearful of punitive sanctions imposed by the police state. Therefore they will be unable to protect the individual freedoms of their customers. No data shall be sacred.”

Steven Swimmer, a self-employed consultant who previously worked in digital leadership roles for a major television network, wrote: “It will become a branding issue for larger consumer-facing companies. But there will always be companies willing to do the deed for money and/or access to markets. Expect selective adherence to these principals. In other words, companies that may not cooperate with small authoritarian governments will be tempted to make exceptions for China and wealthy Middle Eastern countries.”

Larry Lannom, director of information management technology and vice president at the Corporation for National Research Initiatives (CNRI), a research organization based in the Washington, D.C., area, echoed that thought: “At best, those companies who want to pursue those markets will feel compelled to set up subsidiaries and sub-licensees. The only real solution is for authoritarian governments to be dissolved by their own populations.”

Eugene H. Spafford, professor of computer science and engineering at Purdue University and executive director of Purdue CERIAS, wrote: “We are already seeing the ‘democratic countries’ trying to ban or monitor services: the United Kingdom and United States shutting down access to limit protests; Australia passing laws to ban access to what some people consider pornography; the United States and United Kingdom monitoring for terrorists; the United Kingdom passing laws requiring record keeping of all transactions, including law abiding ones; and more. There will be little in the way of the dichotomy suggested by these answers. Instead, there will be a continuum of various forms of regulation, and businesses will tune their models to stay out of the line of fire and remain profitable. Some may adopt the approach of having independent subsidiaries in different parts of the word to carry the brand yet adhere to local regulations—a model used by oil, banking, and telecommunications companies now.”

Anonymous survey participants contributed these thoughts:

— “Technology companies will continue to provide products that can be used for multiple things (after all, the Internet is just a tool), and will continue to interact with governments on those governments’ terms. They will make conciliatory/outraged/apologetic statements as appropriate, but nothing much will change beyond that.”

— “Authoritarian regimes love to play benevolent, as do corporations. It’s in all of their best interest to pay lip-service to free speech, while doing lots of business in interception and content-filtering. This trend has only been accelerating over the past fifteen years.”

— “Firms with Western headquarters will adopt clear policies on R2P, but may spin off subsidiaries and find other ways to work around these limitations.”

A corporation’s purpose is to maximize returns. Both businesses and governments leverage technologies to meet their basic goals.

Some respondents argued that the basic structure of capitalism is what drives the process of how companies engage governments.

Simon Gottschalk, professor in the department of sociology at the University of Nevada-Las Vegas, summed up this view: “The bottom line of any capitalist enterprise is profit and everything can be sacrificed in order to maximize it, including especially the rights of invisible citizens whose only importance lays in their ability to make a monthly payment. Firms might decide to implement steps that protect dissidents only if it is cost-effective for them to do so. In light of the very nature of the capitalist spirit, there is no reason to believe that firms will suddenly (and spontaneously) ‘get religion’ and become concerned about citizens’ rights, especially if they live far away and cannot defend themselves. In addition, the ethical behavior of firms necessitates an educated and concerned citizenship that is informed about the plight of dissidents in other places and that cares about it. The present state of education does not indicate that this level of education/care has been attained. There is no reason to believe that this will change in the next nine years. Au contraire.”

Ross Rader, general manager at Hover and board member of the Canadian Internet Registration Authority, maintained: “Market pressure from competition will always keep commercial operators working on behalf of authoritarian regimes. For each organization that chooses to stand up to the demands of a dictator or tyrant, another will step in to fulfill the request.”

Sandra Braman, professor at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, chair of the Law Section of the International Association of Media and Communication Research, and editor of the Information Policy Book Series published by MIT Press, wrote: “All indicators are that Ithiel de Sola Pool was right in the prediction he made in his 1983 seminal and still important book, Technologies of Freedom. After reviewing the histories of developments in the three very different types of legal systems that were already then being applied to digital technologies—those that developed in response to print, telecommunications, and broadcasting—he argued that as legal frameworks converged in order to cope with converged technologies, it was likely that the most repressive elements of earlier systems would be those that would dominate.”

Fred Hapgood, technology author and consultant, wrote: “The incentives are overwhelmingly on the side of collaboration.”

Matthew Allen, professor of Internet studies at Curtin University, Perth, Australia, and a digital ethics expert and past president of the Association of Internet Researchers, wrote: “There have been many claims for the democratising possibilities of network technologies, which, in truth, are claims that the private corporations that mostly control those technologies have some stake in democratisation beyond the primary goal of making profit and gaining control over markets. In some cases there is an alignment between the interests of specific corporations and the spread of democracy; however, in most cases profit, not politics, will always drive corporate decision making.”

Daren C. Brabham, assistant professor of communications at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, argued: “To think that companies like Facebook and Twitter and Google answer to higher moral standards is a joke. They are for-profit companies that answer to money and shareholders. Citizens’ privacy and democratic organizing are backseat concerns to profit.”

Bill St. Arnaud, a consultant at SURFnet, the national education and research network building The Netherlands’ next-generation Internet, and research officer at CANARIE, working on Canada’s next-generation Internet, maintained: “Although many corporations will pay lip service to things like R2P, in the long run, making money always trumps good intentions.”

David Ellis, director of communication studies at York University, Toronto, wrote that the imperative to maximize sales is paramount: “Much though I would like to see the world otherwise, large technology firms operating globally will always be under intense pressure from shareholders to keep expanding into new markets, developing their customer base, and increasing profits. That means inevitably they will have to do business with authoritarian regimes, as we have already seen in China. Some of America’s most prestigious firms—Google, Apple, Cisco—have already been accused of promoting practices that would not be tolerated in a liberal democracy. I’m pessimistic about any improvement in this trend, not simply because these firms are corruptible, but also because regimes like Iran, China, and Saudi Arabia have set up extremely elaborate systems for filtering and effectively partitioning the Internet. And this movement against an open Internet has a political echo in Washington, thanks to the far-reaching efforts of certain Republicans to eviscerate any semblance of network neutrality rules of the kind proposed by the FCC. The Republican goal of making Internet-related firms unaccountable for their actions will encourage unethical corporate behavior online, as well as undermine efforts to prevent unjust discrimination and traffic filtering both at home and abroad.”

Seth Finkelstein, professional programmer and consultant and 2001 winner of a Pioneer of the Electronic Frontier Award from the Electronic Frontier Foundation for groundbreaking work in analyzing content-blocking software, argued: “Technologies of control have no intrinsic relationship restrictions. If it works on employees of businesses in democracies, it works on citizens of governments in dictatorships. Inversely, if it doesn’t work on citizens of governments in dictatorships, it doesn’t work on employees of businesses in democracies. Pick one. It’s an architectural question. Don’t say your personal moral values are that businesses have a right to control their employees but governments have no right to control their citizens. The dictatorships don’t care about your personal moral values.”

Larry Lannom, director of information management technology and vice president at the Corporation for National Research Initiatives (CNRI), argued: “It will, of course, depend on the company, but as long as there are profits to be made by selling technologies to authoritarian governments it will be done.”

Glyn Moody, self-employed author, editor, and journalist and active voice in online social media networks, wrote: “Technology companies—even the self-styled Googles [‘Don’t be evil’]—don’t really care about human rights. By definition, they care about profit, and so will always be driven to comply with governments who can take away that profit. This is why truly open software, owned by no one, is crucial: It is the last technological bulwark against tyranny.”

Anonymous respondents weighed in with related thoughts:

— “Protesters in my country are terrorists—protesters in my enemy’s country are freedom fighters. Major technology firms are international firms—allegiance is to shareholders not governments. They will do what is necessary to protect their own investments and resources.”

— “We are already headed towards the path of forcing technology firms to expose users’ information in our own democratic country even for non-lethal issues like intellectual property infringement, so they most certainly will not allow protection for more serious needs.”

— “Third scenario: We will place no special burden or expectation on companies like Cisco (which is currently aiding the Chinese government in finding and persecuting dissidents) because we’ve convinced ourselves that placing any such burden would amount to ‘government intrusion on private business’ and most people can’t be bothered to care anyway.”

— “While I would like to be egalitarian and believe the first choice is the [better] scenario, I believe the United States will be one of the first countries not to sign some such pact or will find some way to side-step it under the guise of national security. If anything, our national responses to the events of 9/11 have eroded our civil liberties.”

It’s not a matter of Western nations and their norms vs. authoritarians. ‘Democratic’ countries want to filter, block, and censor the Internet, too. Tech companies see cooperating with governments as a necessity.

Some respondents were swift to note that there is not a clean dichotomy between the liberal West and its firms on the one hand and authoritarian regimes in other parts of the world. The interest in monitoring citizen behavior and at times cracking down on communications, they argued, is an instinct of governments in all kinds of societies. Technology companies have their own reasons for complying with leaders who want to exercise control over citizen actions.

Alexandra Samuel, director of the Social + Interactive Media Centre at Emily Carr University, spoke for many respondents with this answer: “The question isn’t whether democratic countries will expect domestically-based tech firms to respect democratic norms in their work abroad: It’s whether democratic countries will resist the temptation to adopt the authoritarian tactics these technologies enable. The recent use of social media surveillance to respond to the Vancouver riots, which was followed by the UK government’s even more worrying proposal to shut down network access during periods of unrest, is a sign of the shifting ground. Particularly during an era of heightened security concerns, we are vulnerable to arguments about public safety driving us towards very troubling limitations on the use of social and network tools for organizing and dissent. But I chose the optimistic scenario because we do still have a choice, and my hope is that the initial backlash (or at least ambivalence) about state-sponsored surveillance and selective network shutdowns will increase public awareness of the stakes of free access to communications. If that issue becomes a passionate cause in the West, perhaps we will ask companies to hew to the same standards in their work abroad.”

Robert Ellis, a partner with Peterson, Ellis, Fergus & Peer, was pessimistic about the future of privacy: “The future does not bode well for the exercise of First Amendment rights. Anonymity will be forever ended, disguises will be prohibited, and anyone who attempts to protest either online or in public will be forever identified and flagged. The KGB already is beginning to look quaint and benevolent compared to the obsessiveness with which American government agencies are collecting information. The same thing is true for privacy rights. Scott McNealy of Sun had it right when he said, back in 1999, ‘You have zero privacy anyway. Get over it.’ By 2020 it will be far worse. People will be tracked everywhere from cradle to grave.”

Brian Harvey, a lecturer at the University of California-Berkeley, wrote: “So-called ‘democratic’ countries are no better behaved than other countries with respect to spying on their citizens, or, alas, with respect to ‘disappearing’ and torturing enemies of the regime. Somehow Americans have been persuaded that if the disappearee or torturee is Arab or Muslim it doesn’t count. You’re thinking of companies like Google or Yahoo, but it’s the ISPs that are the big problem, and we don’t have to guess about the future—ISPs eavesdropping on their customers for the benefit of the NSA is already the law! Not in China, not in Libya, in the United States.

Nathan Swartzendruber, a technology educator at SWON Libraries Consortium, based in Cincinnati, Ohio, noted: “Who will govern these companies to enforce R2P? Why is Twitter blocking trending of #occupy-related tweets in the United States after allowing the activity that led to the Arab Spring? As long as companies can choose to monitor/block activity based on what they consider to be their own best interests, this activity will likely continue and increase.”

Dave Burstein, editor of DSL Prime and Fast Net News, wrote: “Most technology firms are already deeply collaborating with government security agencies. From Cisco’s huge effort for the great firewall of China to AT&T secretly turning over virtually everything to the NSA, corporations by nature support the powers that be. With only occasional honorable exceptions.”

Peter J. McCann, senior staff engineer for Futurewei Technologies and chair of the Mobile IPv4 Working Group of the IETF, added: “Technology firms have every incentive to cooperate with repressive regimes, and even the so-called ‘democratic’ countries will find reasons to filter and censor the Internet in the coming years. Unless some dramatic political change happens that causes people to rise up against censorship, these trends will continue indefinitely.”

Alex Halavais, an associate professor at Quinnipiac University, noted that security concerns drive behavior in governments of all persuasions: “As cyberwarfare becomes steadily more important, nations will insist on invasive control over large computer services.”

And that thought was echoed by John Jackson, an officer with the Houston Police Department and active leader of Police Futurists International, who argued: “Western nations are increasingly viewing cyber-attacks on public and private infrastructure as a critical national security threat. By 2020, nations will devote substantial portions of their defense budgets to protecting against cyber attacks from autocratic nations. Democratic-nation-based firms will be protected by Western governments.”

James A. Danowski, professor of communication at Northwestern University in Chicago; co-editor of Handbook of Communication and Technology; and program planner for European Intelligence and Security Informatics 2011 and Open-Source Intelligence and Web Mining, 2011, foresees crackdowns by governments if digital communications by dissidents seem to be working: “If attempts to revise government by active protest or resistance continues to spread outside of the Muslim Middle East to Europe and other developed countries such as the United States and increasingly Asian and BRIC countries [Brazil, Russia, India, China], these media will be rendered decreasingly effective for political change. Government agencies are actively working now in developed countries to substantially limit the possibilities for political change through street action. The violence that has typically accompanied these movements will be the primary public relations theme used to justify curtailing these communication capabilities. Commercial firms, particularly as they are capitalized increasingly by the ‘Russian Mob’ and other organized crime, will be decreasingly trusted as partners of the government in filtering and editing information for them. The longer-range trend may more likely be nationalization of key information services, and/or government regulations for commercial firms to comply with government mandates for information and assistance as a requirement for maintaining licenses.”

Anonymous respondents offered important insights:

— “How about asking, ‘What responsibility will tech firms in democratic countries have toward their own citizens?’”

— “This has nothing to do with democratic countries. It’s about capitalism. This question is exactly the one the capitalist system wants you to ask, since it never wants to be noticed.”

— “Depending on the regime, we’ll see action taken by communications companies to support protesters. In reaction to a protest in San Francisco, authorities shut down cellphone service in the BART. We’re likely to see more human rights violations like this in the future.”

— “In 2020, technology firms headquartered in democratic countries will keep track of domestic dissidents at the behest of politicians they put in office. They’ll also track citizens for profit on behalf of marketers, employers, and copyright holders.”

— “Freedom as we know it has reached a zenith; there can only be less in the years to come.”

The result by 2020 will be a mix of the scenarios. Companies will bend to governments’ requests in some cases and respond to public sympathy for dissidents and protesters in others.

A number of respondents challenged the premise of the scenarios. Most said the likely 2020 outcome will be one of the following: things will remain pretty much the same as they are now; it will be a mix of these scenarios; leaders of democracies are just as likely to ask technology companies to block, censor, and spy as leaders of autocracies.

Greg Wilson, a Los Angeles-based marketing and public relations consultant whose work supports organizational change management, argued: “There is a good chance that either of these scenarios could happen, in fact, they already have—Google in China falls into the second choice and the Arab Spring falls into the first. I have selected option one because I hope that the Arab Spring does not stop in the Middle East but continues to trigger uprisings all across the globe wherever people are oppressed. The biggest challenge, of course, will be China. If China is able to contain their housing bubble and avoid a meltdown, they will be the masters of the world, but they are facing a housing bubble so huge that if it bursts they go down and take everyone with them. They will not be the new boss in town and could go to either extreme. It will depend on the people, and the Internet/social platforms will play a critical role.”

Sabeen H. Ahmad, new media director for Brodie Collins Consulting, argued: “It will be a mix but trending toward the side of the latter option, as these companies will be pressured by governments if not fined, to release information. We’re seeing that already in some situations and frankly there are probably a lot of cases of it on a daily basis that we don’t know about.”

Contributors who did not sign their answers also weighed in:

— “This question is wrong. Even the most evil of corporations today recognizes that playing by the rules, while at the same time ‘gaming them,’ is much better than flagrant disregard. I suspect all sorts of technical compliance with the letter of the law, even as I suspect at the same time much disregard of the spirit of the law.” Another wrote, “This area is in flux with neither scenario likely to be reality in 2020. The debate is bound to continue and to the extent there is blocking or monitoring, new technology will likely still provide the means for the Internet activity of protestors.”

— “Both trends will continue in a kind of yin and yang struggle. There will always be black hats and Blackwaters, and there will always be white hat hackers and Wikileaks.”

— “Technology companies will continue to deftly navigate these issues in ad hoc ways that minimize the various political risks (risks of offending domestic and international governments, risks of offending various customer segments) and financial costs (autocratic governments will not pay to have content filtered—they’ll demand it—and the costs of filtering would be borne by companies; litigation—for filtering too much or too little; for disclosing too much or too little—will continue to be expensive).”

— “We are experiencing a change in the way that stakeholders are viewing the companies where they have an interest. We are seeing the rise of more social responsibility and have actually seen some research that shows that firms that are socially and environmentally responsible have stronger bottom lines. There has also been a rise of social entrepreneurs—people who want to balance the social good that they do with the amount of money that they earn. At the same time, big business has come under scrutiny in terms of its social impact and there has been a rise in consumer consciousness about the environment and social justice issues. This is a slow change in corporate social responsibility that may have gained some traction by 2020.”

— “I would like to think that global tech firms would feel certain moral obligations. Some isolated actions by such firms show that this is possible. However, the corporate structure by its very nature is entirely profits driven. I do not see any evidence of that changing, and I do not see any evidence of government regulations that would effectively impose moral obligations on technology firms.”

— “Commercial entities are ultimately governed by a set of rules defined by governments.”

— “In an ideal world it would be scenario one—but this sort of change is usually caused by single high-profile events, with legislation as a backlash. These are hard to predict.”

— “Organizations will continue to choose for themselves whether they kowtow to governments’ requests to block the activities of those they find undesirable or decide to thumb their noses at the governments and choose to uphold the ideals of free speech. The market will allow for both paths to continue, unless, a major radicalization of governments across the world happens in this decade, but it’s hard to say if that will happen sooner or later.”

— “There will be a way around it, but I would expect big technology firms firmly allied with big government and apt to control and report on dissent.”

— “This is a scary and hard one. I’d like to believe the first, but since too many corporations are now also political puppet-masters, the second seems more likely. Trends already in place are not getting the negative response needed to prevent further encroachments.”

— “Global corporations will not respond to moral issues if it does not suit their bottom line to do so. The only exception would be if a ‘responsibility pact’ were issued—however, I cannot see how such a thing would be enforced, especially with blurry political lines (who is right and who is wrong?) and so many politicians who still argue we should be able to wiretap our own citizens who are suspected of wrongdoing.”

— “This outcome is very up in the air! Very recently, we have learned that both autocratic, strongly authoritarian governments, as well as democratic ones, are vulnerable to social network, Twitter-enabled ‘rebellions’ or ‘hooligan-ism.’ I don’t think we know how Western/democratic-sited technology firms are going to react. They seem to be outside the influence of their own governments and ill at ease with brutal regimes’ abuse of their products. Big technology firms may just get out of the business of this level of control. And technology mercenaries will spring up to sell this to anyone.”

Different regions of the world will continue to be defined by different principles and principals, and companies will be forced to adjust to that.

Some respondents were focused on the contingent nature of company behavior in different environments and stressed that there were not-yet-clear forces at work in both Western countries and other places that will likely influence how tech companies operate outside their home countries. Things might change when people in the developing world are enabled by technologies to begin to operate on a level playing field. Some respondents say the billions who will benefit might be much more motivated toward economic benefit and survival than by the ideals of civil rights.

Stowe Boyd, principal at Stowe Boyd and The Messengers, a research, consulting and media business, was a leading voice for this insight: “Tech firms based in Western democratic countries will continue to support the compromises of political free speech and personal privacy that are, more or less, encoded in law and policy today. The wild card in the next decade is the degree to which civil unrest is limited to countries outside that circle. If disaffected youth, workers, students, or minorities begin to burn the blighted centers of Western cities, all bets are off because the forces of law and order may rise and demand control of the Web. And, of course, as China and other countries with large populations—like India, Malaysia, and Brazil—begin to create their own software communities, who knows what forms will evolve, or what norms will prevail? But they are unlikely to be what we see in the West. So we can expect a fragmented Web, where different regions are governed by very different principles and principals.”

Henry L. Judy, an attorney contracted for his expertise in corporate, commercial, technology, and financial law by Washington, D.C., firm K&L Gates, said: “I do not think that China, Russia, Iran, Vietnam, Saudi Arabia, and a host of Internet-restricting countries are likely to change their ways. The most likely outcome is that the Internet-restricting countries are most likely to develop their own Internets and operate the equivalent of ‘dual Internets,’ excluding Western communications firms entirely.”

Pamela Rutledge, director of the Media Psychology Research Center at Fielding Graduate University, argued: “There is a complex issue of bias in assigning corporations a moral responsibility to enforce cultural and political values. The issue is not putting a company in disfavor with autocratic governments, but what culture or current belief system writes the norms to be enforced. Throughout history, we have seen people with good intentions doing what we would now consider abhorrent. We have to control our own tendency toward solipsism and moral colonialism.”

Richard Lowenberg, director and broadband planner for the 1st-Mile Institute; a network activist since the early 1970s; author of the State of New Mexico’s “Integrated Strategic Broadband Initiative”; and an integrator of rural community planning with network initiatives globally, spoke strongly for this point of view: “There are no ‘democratic societies’ (noun); only an increasing number of variations on the theme of ‘democratization’ (verb). A healthy future must include being smart about the balance between public and private sectors and interests. Increasing numbers of corporations have off-shored, bottom-line interests in addition to their (multi)national interests and locations. Managing 7 billion people is a frightening prospect for those in power (rightly so), whether corporate, government, or military/intelligence entities. (Inter)national security must be based on an ecological context for the fragile balance between competing and cooperating interests and intentions. Narrowly biased, reactionary responses to the complex disruptive forces emerging and being given voice in the information revolution are very likely.”

Stephen Masiclat, an associate professor of communications at Syracuse University, wrote: “The most likely scenario is that transnational [companies] will present a democracy-loving face to democratic nations, but take steps to protect themselves in rich autocratic nations. This will be easier as data and computing expertise becomes global. Moreover, corporations can simply outsource data operations to other countries, thereby relieving themselves of the full risk of setting data policy.”

Giacomo Mazzone, the head of institutional relations for the European Broadcasting Union, maintained: “The power of orientation of citizens of the more-developed countries will soon and dramatically decrease. When grown-up segments of business originate within countries in development—where the attention is less focused on civil rights and more on spreading economic benefits to the whole population—the consequence will be less attention to concepts such as freedom of expression or civil rights or the protection of privacy. This erosion of weight of civil rights activists, luckily, will not happen completely before 2020, but we shall be already far advanced on that way.”

Here are some of the writings of anonymous respondents who embraced this line of thought:

— “Companies will respond to the incentives in the different places where they operate. And they will know how to hide their differing activities, so that activists in democratic countries will never know that a company is deriving significant income from cooperating with authoritarian regimes. Companies will do what they have to and what they can get away with, and will be creative in managing the various situations in which they find themselves.”

— “Cultures and conflicts will not allow this to happen. Women still can’t drive and vote in different countries, so I can’t believe communications will all be equal.”

— “There will be a gap between intentions and reality. On the intention level, there’s already a strong movement toward the protection scenario. On the reality level, international policies being what they are, it will be culturally and economically impractical to implement such protections outside of societies that share similar definitions of social and human rights. This is sheer arrogance and a continuation of colonialist mentality on the part of (particularly) American corporations—the idea that American notions of ‘rights’ have any application outside their own economy.”

— “I made a choice here, but I don’t really agree with it. Vodafone Egypt is subject to the law of Egypt, and the fact that it is headquartered elsewhere isn’t especially relevant when the Egyptian government decides to decree an Internet shutdown. I don’t believe that adopting a set of norms in one region of the globe can really improve the situation for people on the ground in another region, unless the authorities in that region can also be enjoined to adopt similar norms there.”

Some warn that corporations could rival governments in influencing the digital future around the globe.

A number of respondents took the view that firms, rather than governments, will eventually set the course of how protestors and dissidents might be treated.

David Kirschner, a Ph.D. candidate and research assistant at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, wrote: “We’re moving more toward a world where global firms are more and more allied with government and vice versa. We’re moving toward a world in which everything we do is tracked and monitored. Global tech firms will greatly influence political policies, and all governments, but especially more centralized ones, will greatly influence the policies of firms, as they relate to customer privacy, because, you see, customers and citizens are becoming closely tied together as well. To the extent that there is marriage between global corporations and governments, there will be marriage between the concepts of customer and citizen. Dangerous.”

Ondrej Sury, chief scientist at the .CZ Internet registry, added: “I foresee the governments becoming the puppets of big companies and not the big companies dancing as the governments whistles.”

Michel J. Menou, visiting professor at the Department of Information Studies at the University College London, argued: “Beyond democratic and authoritarian regimes, the scenarios neglect the existence and rising importance of a third type of regime, the one of the global techno-structure to which major technology firms belong. They will primarily serve their own interests, which are ably disguised into concern for public interest in the corporate, social, or environmental responsibility statements. The question is whether the people’s democratic choices will or not have a bearing upon corporate decisions. On the light of current accomplishments one can only be pessimistic.”

John Capone, a freelance writer and journalist and former editor of MediaPost Communications publications, wrote: “People will fear corporations more than their governments. For instance, ‘Google might see we said something bad about it and penalize us in search results,’ is already a common sentiment.”

One anonymous respondent wrote: “Norms will be made and broken at a rapid rate. Governments as we understand them may be an anachronism.”

Additional anonymous responses:

— “Clearly, tech firms are moving toward subtle control of how media is dictated and disseminated. As the consolidation of this media continues, the ability to control will become more effective and dominant.”

— “Cisco helped create the Great Firewall of China, while Google withdrew from China when it felt that the government was asking them to compromise its search service too much. Telecoms folded when the Egyptian government asked them to shut down mobile services during Arab Spring. But Twitter didn’t fold. This means that large technology/communications companies are going to have a greater role than ever in shaping the public sphere the way governments do.”

— “Companies with money run the governments.”

—“There will be more firms that take the stand in the second paragraph, and there will be a significant number of companies that maintain the stance of the first paragraph. This is much less about the countries than the companies. Which will be more powerful in 2020? I think the companies are more on the ascendancy at the moment, and it’s likely to play out in their favor over the next ten years.”

— “Already, global corporations are outstripping governments as change agents and have hijacked democratic processes. So the phrasing is not quite right: Corporations will continue to entrain governments, and corporate technologies will have as their main purpose attempting to control consumers—which is what citizens will have become.”

Some asked: How do we inspire freedom-enhancing practices? Through regulation? An organized global movement? Better childrearing?

Several respondents mentioned the Global Network Initiative, a non-governmental organization formed in 2008 by a coalition of multinational corporations, nonprofit organizations, and universities to protect individual rights and prevent Internet censorship by authoritarian governments. Microsoft, Google, and Yahoo are active corporate participants, but survey respondents say it has not yet had significant impact.

Susan Crawford, a professor at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government, former ICANN board member, and President Obama’s Special Assistant for Science, Technology, and Innovation Policy, was one of those writers: “Many of us had a lot of hope for the Global Network Initiative, but it’s gotten bogged down in its own process and hasn’t attracted any non-US (or non-Google, MSN, Yahoo) adherents. In the absence of a collective initiative it seems unlikely that there will be any upside for any individual company that might want to resist the demands of governments—including the US government—when it comes to squelching connection and speech. Indeed, all companies want scale and certainty, and those things come to cooperative entities. I still have hope that multistakeholder efforts, particularly at places like the OECD, will bear fruit. But it takes an awful lot of work and time for that fruit to grow, and at the moment we have just barely identified the territory.”

Charlie Firestone, executive director of the Communications and Society program at the Aspen Institute, a nonprofit organization based in Washington, D.C., noted: “Efforts such as the Aspen Institute IDEA Project are working on establishing multi-stakeholder processes to bring about global norms for these and other trans order issues.”

Susan Price, CEO and chief Web strategist at Firecat Studio LLC and TEDxSanAntonio organizer, wrote: “We need an opt-in, open-source like Global Human Bill of Rights and an associated Human API to pull this off. The increased openness and transparency the Web has made possible is the way we can make this happen.”

Rob Scott, chief technology officer and intelligence liaison at Nokia, argued: “Technology firms will minimize the ability to be used as tools of either governments or individuals simply to reduce contingent liability. To those who believe that corporations will develop a sense of right and wrong, I must point out that without a near-dictatorial ruler, the chaotic, work-avoiding, and gain-seeking nature of the individual will be expressed in an ‘it’s not my job’ effect that will allow corporations to behave in misanthropic ways. Similarly, to those who believe corporations are evil incarnate, I assert that these entities cannot execute in an evil manner long term without some express or almost complete tacit approval of the individuals making up the board and management team. If we learned nothing else of the near meltdown of our banking system, we must take away an understanding that our society will only recover from this travesty and prevent future recurrences by holding corporate leadership both civilly and criminally responsible for the breakdowns. While bills of attainder are prohibited by our constitution, our political system must learn to react swiftly and strongly to each corporate attempt to slip through the cracks and exploit loopholes. This, in turn, will bring about greater and greater risk aversion and in inculcation of automatic risk shedding into publicly-transited systems and services.”

Marcel Bullinga, futurist and author of Welcome to the Future Cloud – 2025 in 100 Predictions, made the case for the basic notions of reform to be inculcated in families: “What we have seen so far is that democratic countries and multinationals in democratic countries most happily cooperate with authoritarian regimes if it serves them right (oil, raw materials). Please, parents of the world, start raising your children again and teach them about the virtue of doing good. Back to the 1950s!”

Anonymous participants in the survey offered a variety of similar observations:

— “The vision you paint of tech firms abiding by a set of pro-democratic norms is one that American companies, as leaders in the field, must not only embrace but proselytize. I have seen evidence that various existing firms have not embraced this goal; however, as evidenced by the sparse adherence to the Global Network Initiative. This is an area in which the U.S. government must lead, prod, and nudge.”

— “You can’t lump all tech companies into the same category. This definitely depends on the organization. Different companies have varying levels of commitment to defending human rights. We give a lot of credit to Twitter for its role in Iran, but Twitter refused to join the Global Network Initiative. Likewise, Facebook also refused to join. Other companies, however, including Google, Microsoft, and Yahoo joined GNI.”

— “Corporate culture is not easy to change and to do so at all requires leaders to sustain intervention policies and actions for a meaningful length of time to bring about wanted change. I am afraid we have neither the leaders nor the time for that to occur by 2020.”

— “We can’t get our corporations to behave domestically. How in the world can we get them to be good global citizens? Corporate globalization just means new labor to exploit and new markets to sell to.”

— “Democratic norms will definitely be in place, and governments and firms will find a way around them when expedient. The decisions will be behind the scenes. For instance, what BART did in San Francisco in August 2011 and the several points of view about the stoppage.”

— “Government will have to set the limits and boundaries first, and negotiate with corporate entities or enforce policy via litigation. Same problems as with enforcing the civil rights laws.”

— “In order to keep the Internet open and effective, companies will have to adopt norms in order to ensure that their products and services do not harm users or facilitate repressive governments. If they do not, the Internet will likely deteriorate as an open platform.”

— “The move to regulation will be minimal.”

— “I hope that responsible, principled policies will emerge, though I say this even as the British government considers restricting the availability of social networks during times of unrest. I think that it’s imperative that national governments of democracies make plain their principles so as to provide working guidelines for companies in their jurisdictions too squeamish to stand by principles of their own. I don’t expect it to happen anytime soon.”

— “The primary aim of corporate capitalism is to maximize profit while externalizing cost. Unless there is a coordinated international effort to deny technologies to authoritarians through embargoes or sanctions, any attempt to regulate the sale of such technologies will simply be to remove the bits of the company involved in such sale from the jurisdiction of regulation. Since most of these governments themselves would like to avail themselves of the same technology to monitor and block certain Internet traffic, I would be astonished if there was any movement in the direction of embargoes or sanctions. In the case of China, it is already too late: Their local industries are competent enough to provide such technology without worrying about the opinion of Western suppliers or customers.”

Anonymous respondents noted that the United Nations or the Internet Governance Forum might be places in which agreements or suggested principles could be discussed. One said, “Seems like a logical extension of government, though I’d expect it to come from an international group, i.e., United Nations.” Another noted, “Transparency—legislated by the United Nations—will reveal corruption, malfeasance, inefficiencies by corporate or elected officials. Attempts to thwart these will quickly be exposed. Everyone will be better off.” Another said, “The Internet Governance Forum will be central in this evolution.” But another wrote, “As I check the UN direction regarding war, rights, and protection of worldwide citizens, I sadly realize how ineffectual it is in our power-hungry world.”

An anonymous respondent makes the case for these powerful companies to dig in and prepare in advance for facing difficult ethical scenarios in the future:

“There have been situations in which mobile phone networks have been ‘turned off’ because of a cited need to maintain public safety, such as in UK terror attacks in the 1980s and 1990s, when the cellular channels were all needed by emergency services. The recent Arab Spring scenarios of government intervention and requests for closing down service are not entirely new issues for providers of telecommunications, although Wi-Fi is a perhaps a different matter from cellphone coverage. Nevertheless, they are new issues for people—the users—who have become accustomed in the last few years to instant access to always-on communication. There is a new tipping point emerging and telecoms operators may be forced to make some uncomfortable decisions about what is within their own control and what is part of their regulatory as well as corporate responsibility.”

The scenarios presented in this question completely neglect other significant influences, locally, regionally, and globally.

There were two other major themes that were most notably sounded by anonymous respondents. The first has to do with the limits and biases of the scenarios that were sketched out in the survey. Here were some of the thoughts tied to that:

— “The question appears to assume that Western telecommunications firms will be major players in Internet access in foreign countries—that’s a flawed premise and cite the following counter-examples that are more indicative of the trend, in my opinion: 1) Google cut back activity in China. The Chinese Internet seems to be doing just fine. 2) When Egypt shut down the Internet in Egypt earlier this year, the shutdown was accomplished entirely via Egyptian telecommunications companies; not a single Western company was involved. I think Western telecommunications companies will become more responsible, but as a consequence of that responsibility they will be forced to limit their activities in authoritarian countries.”

— “There is a Western bias/shortsightedness in this question. The global action will have shifted to Asia, Africa, and Latin America by 2020. The West may become the third world of the future.”

— “Authoritarian regimes and ideologies already seem far better at affecting behavior in democratic countries than vice versa. Given China’s global economic leverage at the moment, it is hard to see any actor resisting its authoritarian influence.”

— “Neither scenario is in any sense realistic. Look at the attempts to rule the online world, by the US government in particular, through bilateral and multilateral trade agreements, the greedy moves by big corporations for copyright protection. These will be of much greater significance.”

— “Governments may make corporate responsibility or irresponsibility a moot point. The governments will take down sites unilaterally if they feel it is a problem—including democratic governments. The revolution will not be televised—or on Twitter—unless the governments says it can happen.”

Regulation, guidelines, standards, or principles may come to pass, but they won’t necessarily improve things.

A second theme carried in a number of the unsigned answers was that there might not be a way for technology companies or anyone else to promote freedoms in authoritarian places.

Anonymous responses included the following:

— “Domestic and international security has always been given a higher priority than individual freedoms. There is no reason to think the Internet will change this.”

— “The 2010s or 2020s decade will explode in papers related to corporate responsibility. Many lectures, congresses, and acts will be developed. Declarations and compromises will be made. In the end, a new Patriot Act will come back to sweep all in the name of national security; secret services will continue monitoring communications; some organizations will still be bugging some public figures; and corporate leaders will continue doing what some members of their councils require, if it will produce money.”

— “Corporations will take over more and more of the services and programs of government, under the guise of corporate social responsibility (CSR). At the onset this will be viewed positively, as the way that corporations give back to society. Over time we’ll come to see this as ‘unrepresentative’ government, but dependence will be too great for backing away from this model of CSR.”