Many people stare down face recognition technology every day as they unlock their smartphones. But this technology also has applications in people’s places of work. Employers can use it to clock workers in and out, screen candidates during the hiring process or even monitor employees’ productivity. While some employers say this technology will increase efficiency, others worry about bias. Critics point to many systems’ lower accuracy rates for identifying people with dark skin complexions. Some programs are also designed to infer emotion from facial expressions, which some studies suggest is hard, if not impossible.

These varying views show up in the new Pew Research Center survey. The majority of U.S. adults oppose employers’ use of face recognition technology to analyze employees’ facial expressions, but views are more mixed about using the technology to track employee attendance. And Americans are not convinced of face recognition’s accuracy, with a majority saying it would misinterpret expressions and about half saying that it would misidentify workers or recognize some skin tones better than others.

Amid debates over the ethical use of workplace face recognition and a hodgepodge of state regulations governing it, there are differences among Americans in their awareness of the technology. Six-in-ten adults say they have heard or read at least a little about employers’ use of face recognition technology in the workplace. This includes only 14% who have heard a lot about this practice.

Some groups are more likely than others to say they have heard about the use of face recognition in the workplace. For example, men are more likely than women to report they have heard a lot or a little. Majorities across racial and ethnic groups say they have heard about face recognition in the workplace, though Asian adults are more likely than Hispanic, Black or White adults to say so. College graduates are also more likely than those with some college experience or a high school education or less to have heard about this technology. See Appendix B for full demographic details.

A majority of adults oppose employers using face recognition to analyze employees’ expressions

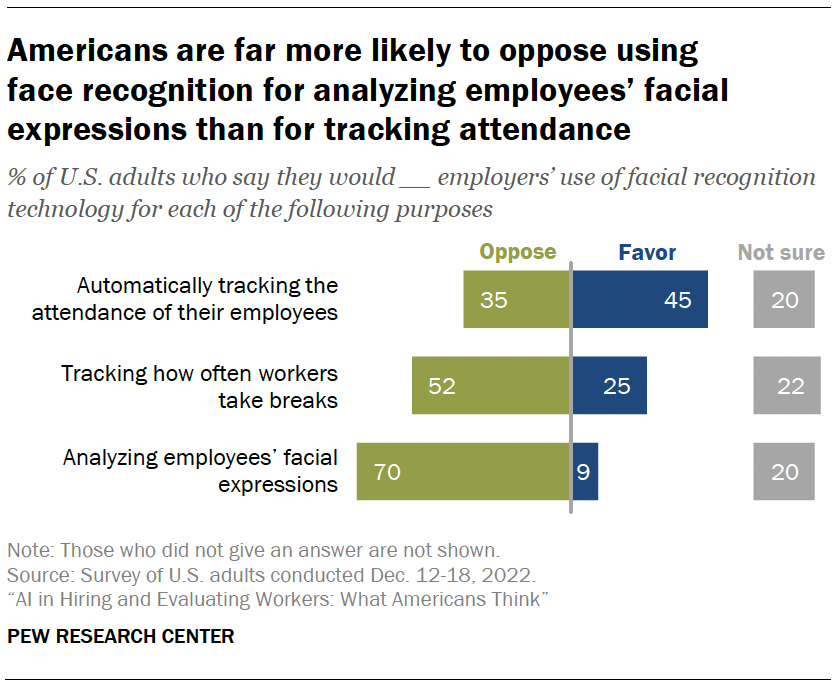

Americans’ attitudes toward face recognition vary based on the reasons employers are using the technology. For example, seven-in-ten adults say they oppose employers using face recognition to analyze workers’ facial expressions. Fewer Americans are skittish about the use of face recognition to track how often employees take breaks, although roughly twice as many oppose this as favor it. And while about a third of Americans oppose employers using face recognition to automatically track the attendance of their employees, a larger share (45%) favor this action.

It is important to note that for each of these use cases, about one-fifth of respondents say they are not sure how they would feel about employers using face recognition in these ways.

Younger men tend to oppose employers’ use of face recognition for a variety of purposes

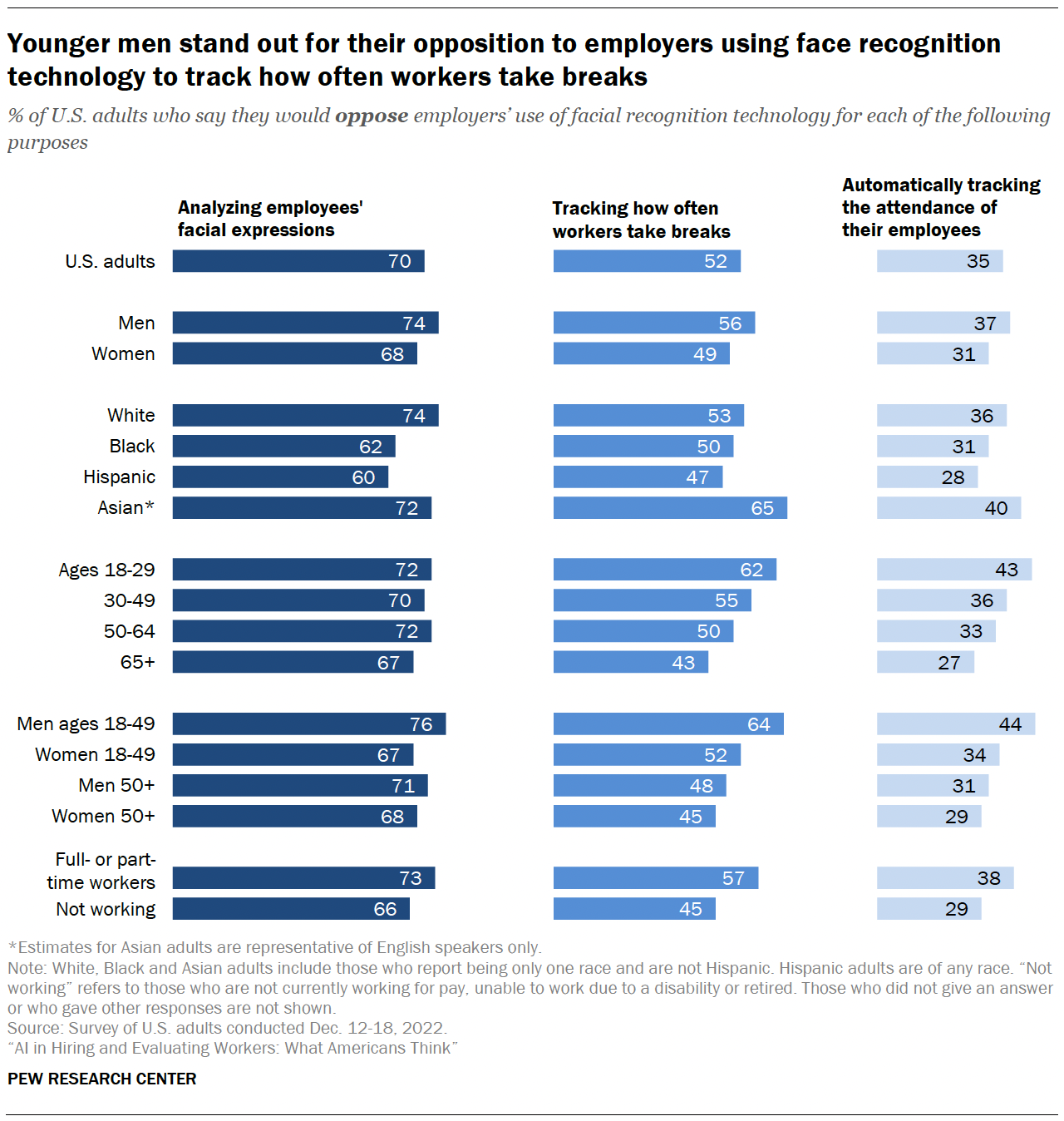

Americans’ views on face recognition in the workplace differ across demographic groups, including age and gender. While there are few age-related differences in opinion when it comes to analyzing employees’ facial expressions (roughly seven-in-ten adults oppose this in each age group), younger adults oppose tracking workers’ breaks or attendance with face recognition at higher rates than older adults.

Overall, men are more likely than women to say they oppose all three of these uses of face recognition technology. This difference is present among younger Americans, but not for older adults: Among Americans 50 and older, men and women do not diverge significantly in their opposition levels. In contrast, for all three of these use cases, men under 50 stand out from older men – and from women regardless of age – for their opposition to face recognition technology. For example, a majority of men under 50 (64%) oppose employers using face recognition to track workers’ breaks. About half or fewer of men over 50 and women in either age group say the same.

There are also some differences by race and ethnicity when it comes to workplace applications of face recognition. Larger shares of Asian adults than of Black or Hispanic adults report opposing each of these uses. And White adults are more likely than Black or Hispanic adults to oppose analyzing facial expressions and attendance.

Views also vary by employment status: Those working for pay disagree with employers’ use of face recognition technology in all three of these ways at higher rates than those not currently working. And opposition rises with more formal education: For example, 63% of adults with a bachelor’s degree or higher oppose using face recognition to track breaks, versus 54% of those with some college experience and 40% of those with a high school diploma or less. Those with less education, on the other hand, are more likely than others to say they are not sure how they feel in this instance (29% of adults with a high school diploma or less say so, versus 20% of those with some college experience and 16% of those who have a bachelor’s degree or higher.)

For all of these applications of facial recognition, those more familiar with the use of this technology in the workplace tend to have an opinion on its use, be it positive or negative. For instance, roughly three-in-ten of those who have heard nothing at all about facial recognition in the workplace (31%) say they are not sure whether they would favor or oppose tracking attendance with this technology. This share drops to 14% for those who say they have heard a little and 8% for those who have heard a lot. Adults who have heard anything about face recognition in the workplace are both more likely to favor and more likely to oppose all three uses when compared with those who have heard nothing at all.

Plurality of adults say employers’ face recognition technology would make mistakes in various ways

Even as face recognition technology develops at a rapid pace and gains more applications, public concerns swirl about its potential for error. Some question technology’s ability to interpret humans’ emotions from their facial expressions, while others point to evidence of racial bias in the systems.

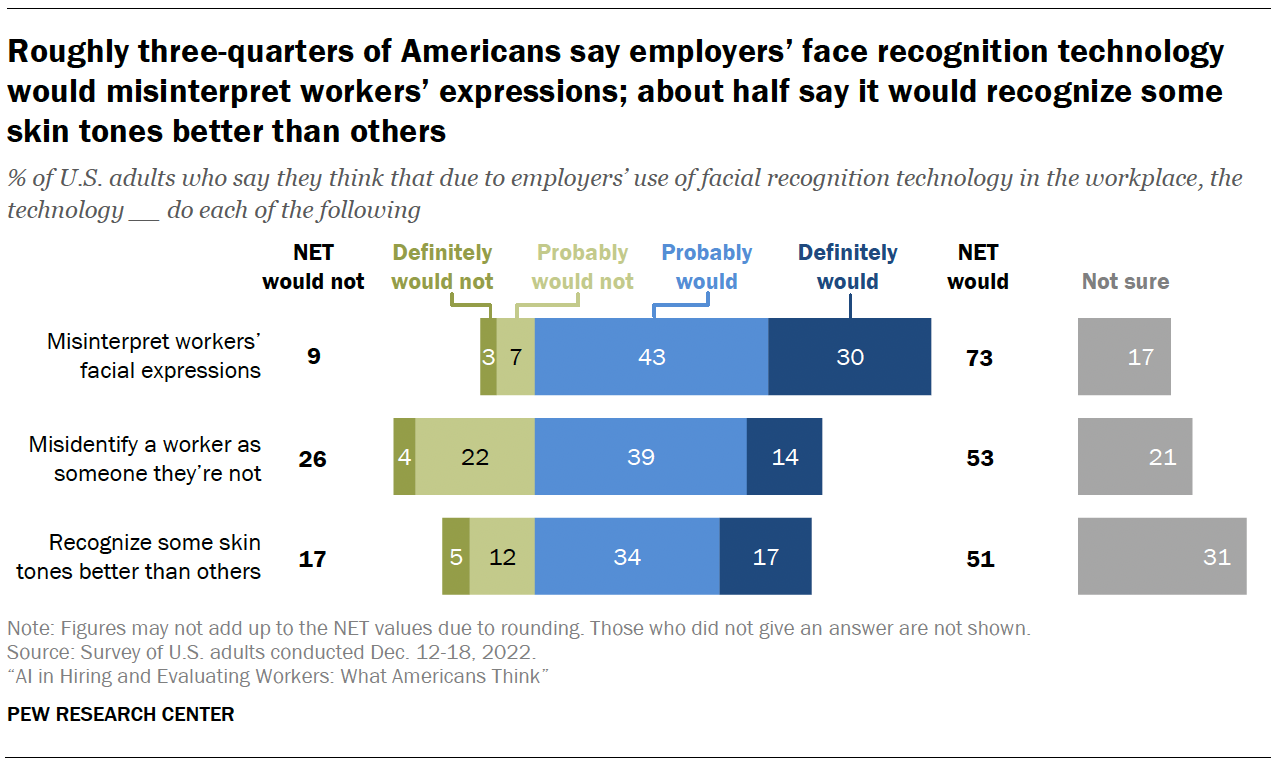

When asked about some ways in which facial recognition might make mistakes, large shares of Americans say the technology would have a range of problems. A majority (73%) say face recognition technology used by employers definitely or probably would misinterpret workers’ facial expressions. Roughly half of adults say it is likely that this tool would misidentify a worker as someone they’re not or recognize some skin tones better than others. Still, about a quarter of adults say that they do not think face recognition technology would misidentify workers.

Notable shares are uncertain whether some of these scenarios would happen. About a third of Americans (31%) say they are not sure if employers’ face recognition technology would recognize some skin tones better than others. In contrast, more adults have an opinion on whether face recognition would misinterpret workers’ expressions: Some 17% report uncertainty on whether this would happen.

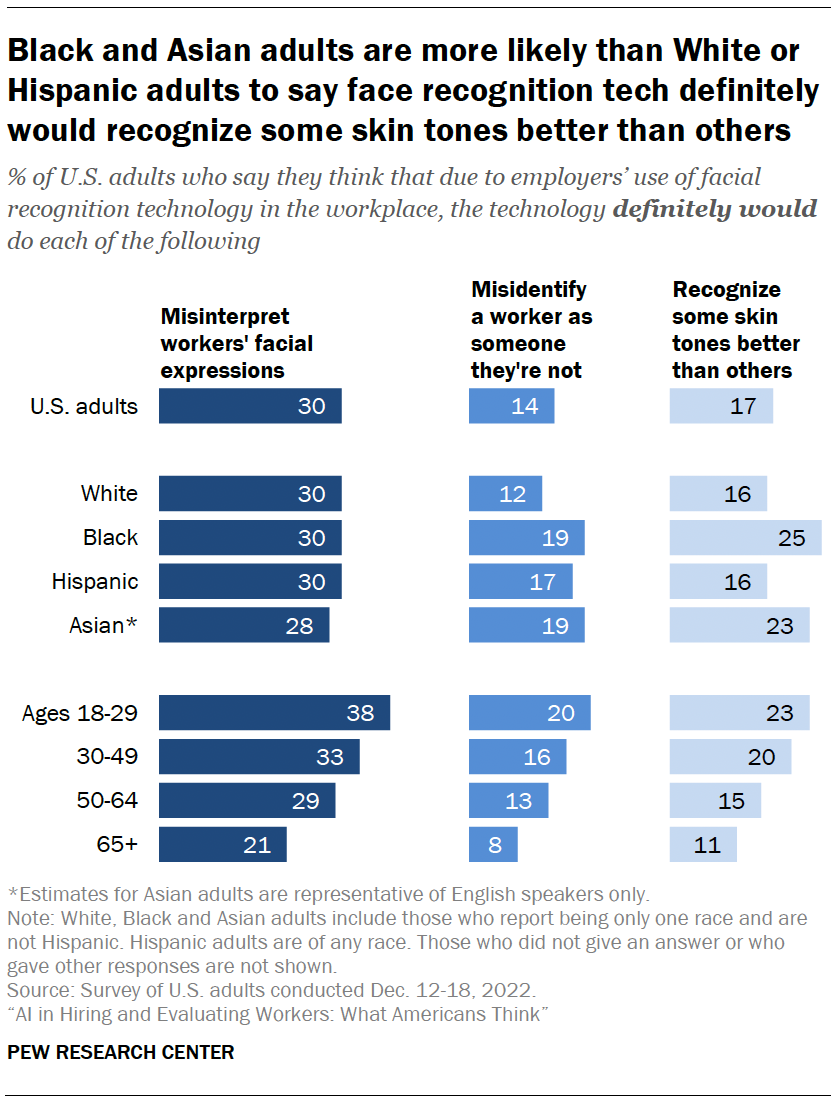

There are some racial and ethnic differences in how adults think about the likelihood of these potential outcomes from the use of face recognition systems. Black (25%) and Asian adults (23%) are more likely than White or Hispanic adults (16% each) to say face recognition technology used in the workplace definitely would recognize some skin tones better than others. Roughly one-in-five Black, Asian and Hispanic adults say that face recognition technology definitely would misidentify workers, versus a smaller share of White adults who say the same. About three-in-ten adults in each racial or ethnic group say face recognition would definitely misinterpret workers’ expressions.

Opinions on the plausibility of these mishaps occurring also vary by age. Adults under 50 are more likely than older adults to think face recognition technology used by employers would definitely misinterpret facial expressions (35% vs. 25%), recognize some skin tones better than others (21% vs. 13%) or misidentify workers (17% vs. 11%).