As the pandemic unfolded in spring 2020, many Americans saw their lives swiftly reshaped by stay-at-home orders, school closures and the onset of remote work. From video calls with isolating or sick family members to holiday celebrations by video call amid canceled travel plans, social distancing recommendations altered major life events and elements of daily life alike.

Technology bridged physical distance as restrictions continued. Religious services, doctor appointments and essential errands moved online. At the same time, organizations implementing remote work and Americans spending more time online worried about “Zoom fatigue” and tech burnout.

Relationships also evolved during this uprooting of typical routines. Pandemic “pods” helped some Americans maintain connection, but they complicated relationships and family dynamics at the same time. In some cases, friendships relied on technology to stay afloat. And others needed to find new ways to connect amid growing isolation.

With this broader societal context in mind, this chapter explores the ways in which Americans’ lives changed in the pandemic – and the ways that technology was a part of several transitions. Results from the April 2021 Pew Research Center survey show that even as a majority of Americans considered the internet essential to them personally during the pandemic and four-in-ten used tech in new ways, some feel worn out or fatigued from video calls and a quarter feel less close to close family members than before the coronavirus outbreak. The following sections explore these findings.

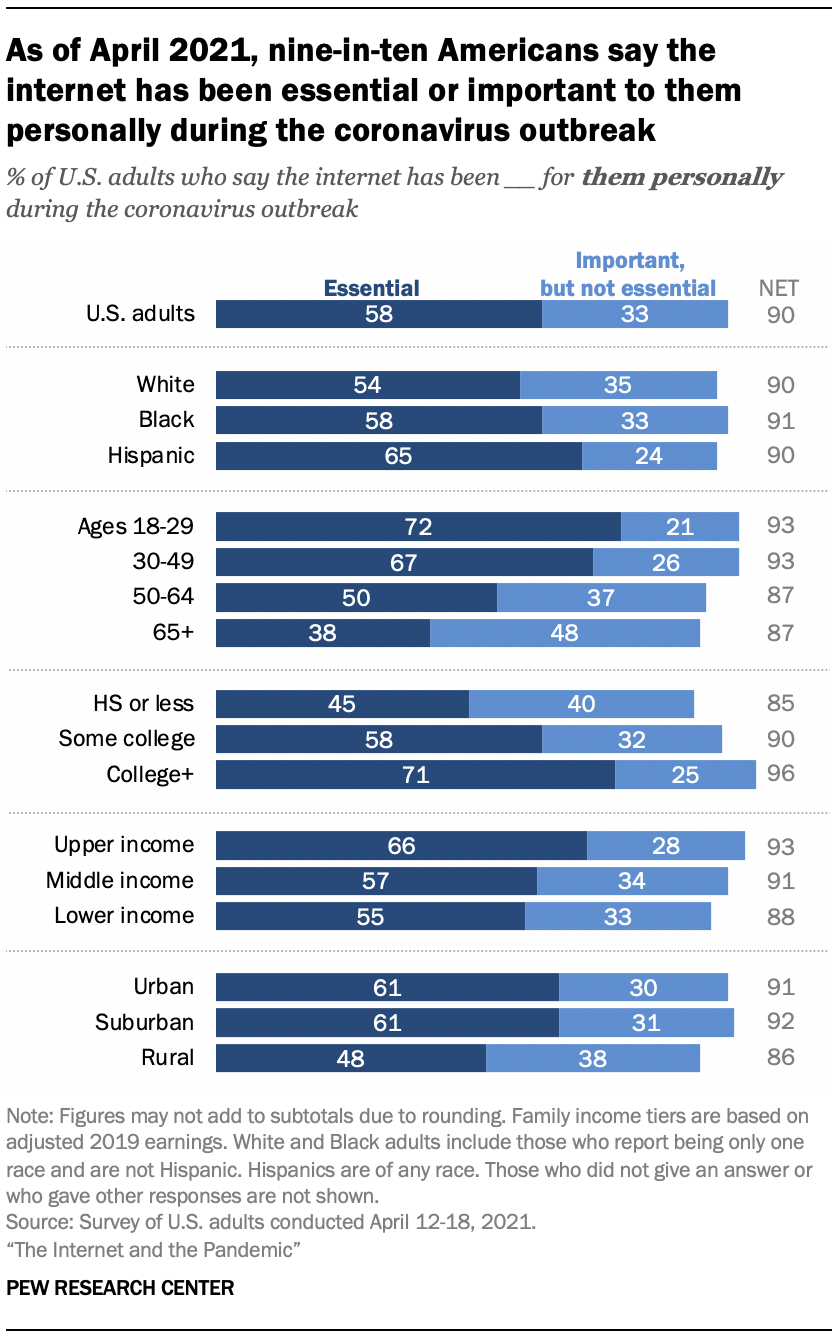

58% of adults say the internet has been essential during the pandemic, and for some groups, its importance grew over the past year

The share of Americans who describe the internet as essential for them during the pandemic has risen slightly over the past year. As of April 2021, 58% of U.S. adults say this, compared with 53% in an April 2020 Center survey.

Americans varied in their reliance on the internet and some of the key differences relate to age, race and ethnicity, educational attainment, income and community type. For example, roughly seven-in-ten adults ages 18 to 49 (69%) say the internet has been essential to them personally, compared with half of those ages 50 to 64 and about four-in-ten Americans 65 and older.

Additionally, about six-in-ten of those living in urban or suburban areas (61% each) say the internet has been essential to them, compared with a smaller share of those living in rural locales (48%) who say the same. While at least half of adults across major racial and ethnic groups say this connectivity has been essential, Hispanic adults (65%) are more likely to say so than White adults (54%). Some 58% of Black Americans say the internet has been essential in this way.

Several of the groups that are less likely to say the internet has been essential also have lower rates of home broadband adoption and smartphone access, according to other Center research. For example, digital divides have persisted in recent years even as Americans with lower incomes have made gains in tech adoption. And as of 2021, a quarter of U.S. adults 65 and older say they do not use the internet.

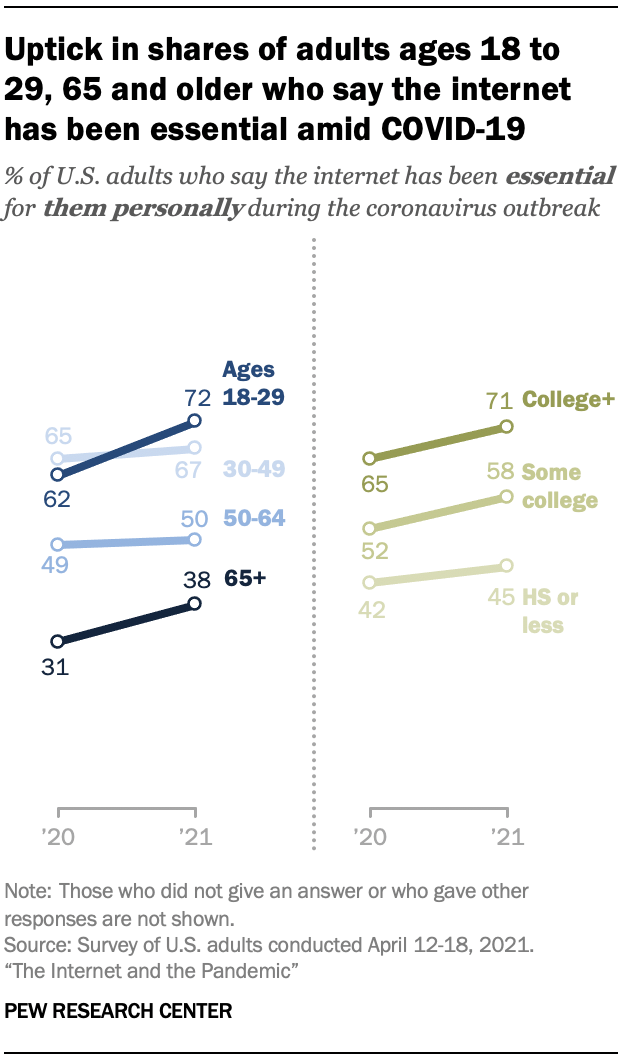

For some groups, the importance of the internet has grown over the past year – especially when it comes to age and educational attainment. The share of adults ages 18 to 29 who say it has been essential during the pandemic rose 10 percentage points between April 2020 and April 2021. Similarly, roughly four-in-ten adults 65 and older (38%) now say the internet has been essential to them, compared with about three-in-ten who said so in April 2020.

Americans with higher levels of educational attainment are more likely today than a year ago to say the internet has been essential to them during the pandemic. For example, 71% of those with a bachelor’s or advanced degree say this, up from 65% in 2020. This uptick also appears for those with some college experience, while sentiments among those with a high school education or less have remained stable.

Looking at older Americans specifically, adults ages 65 and older with a bachelor’s degree or more education are more likely now to say the internet has been essential to them personally (50% say so) compared with a year ago (39%) – an 11 percentage point increase. By contrast, among those 65 and older who have less education, the shares saying it has been essential are similar between the two time points (27% in 2020 and 32% in 2021).

Adults ages 50 to 64 with a bachelor’s or advanced degree are also more likely now to say the internet has been personally essential (a 7-point increase since 2020), while there has been no change for those in that age group with less formal education.

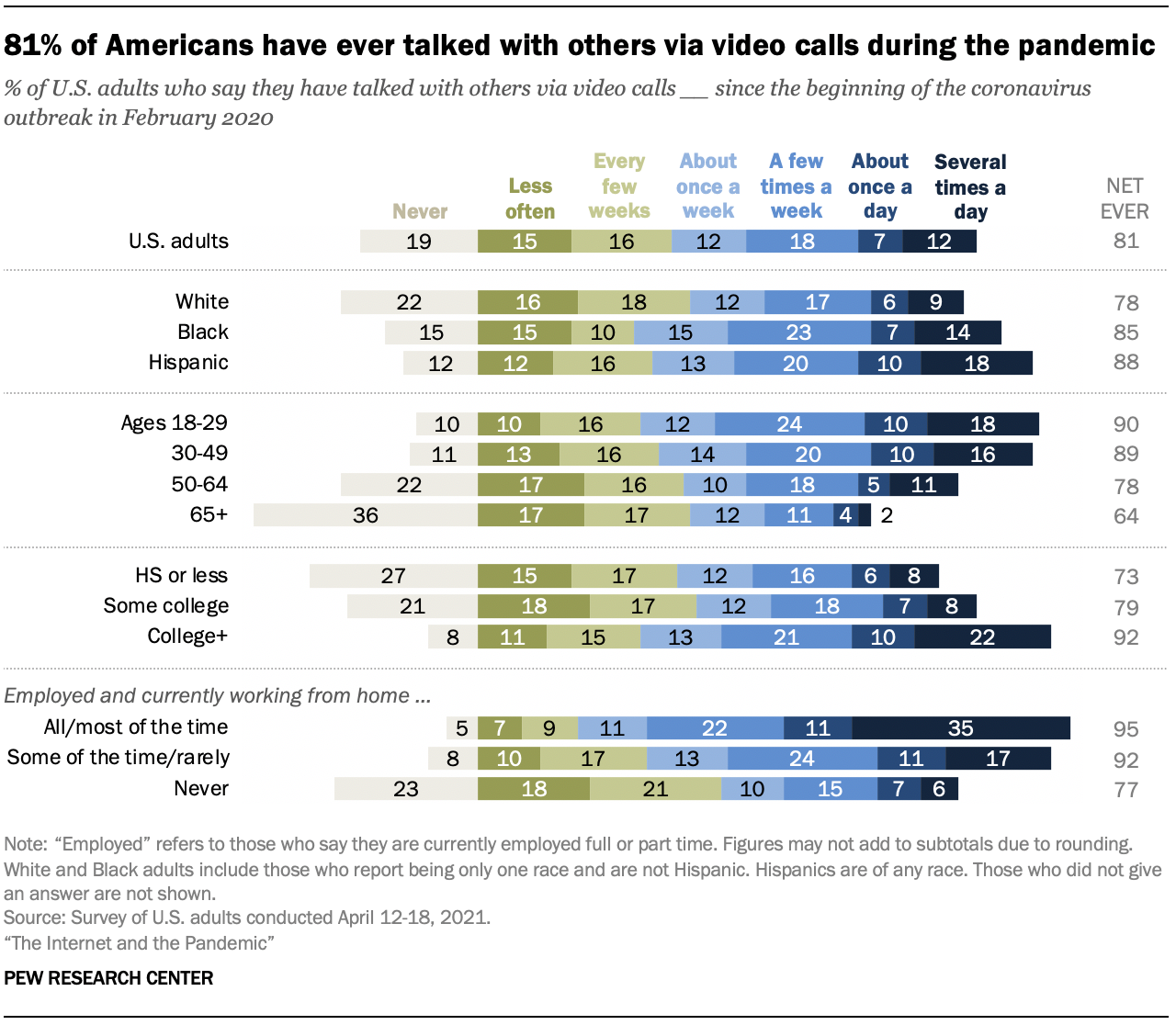

81% of Americans have used video calling and conferencing during the pandemic

As Americans increasingly lived their lives from home, video calling and conferencing platforms became a venue for everything from celebrating holidays with family and friends to conducting remote meetings or visiting doctors.

Roughly eight-in-ten Americans (81%) say they have talked with others via video calls since the beginning of the pandemic. One-in-five have done so about once a day or more often, including 12% who say they are on video calls several times a day. Another three-in-ten have done this about once a week (12%) or a few times a week (18%), and a similar share use video calls every few weeks (16%) or less often (15%).

While there are many ways people can spend their time on video calls, the survey finds that working from home is particularly associated with this type of screen time.

In this survey, 17% of Americans say they were employed full or part time and working from home all or most of the time as of April.7 Among them, 46% say they have used video calling about daily or several times a day during the pandemic. Another 12% of the full adult population was employed full or part time and working from home some of the time or rarely at the time of the survey. Among that group, 28% say they have used video calling about daily or more. And among the 28% of U.S. adults who were working but never from home, 13% say they are on daily or more frequent video calls.

Aside from work-from-home status, how often people use video calls varies by several other demographics. Black and Hispanic adults are more likely to have used video calling than White adults. Hispanic adults are more likely than White Americans to have done so several times a day or about daily. Meanwhile, while about two-thirds of adults 65 and older have made video calls in the pandemic, daily use is more common among younger adults. About a quarter of those 18 to 29 (28%) and 30 to 49 (26%) say they have done this about daily or more often, compared with 16% of those 50 to 64 and 7% of adults 65 and older.

Frequency of video calling varies by education as well. About a third of adults with at least a bachelor’s degree say they have done this at least once a day, compared with smaller shares of those with less formal education.

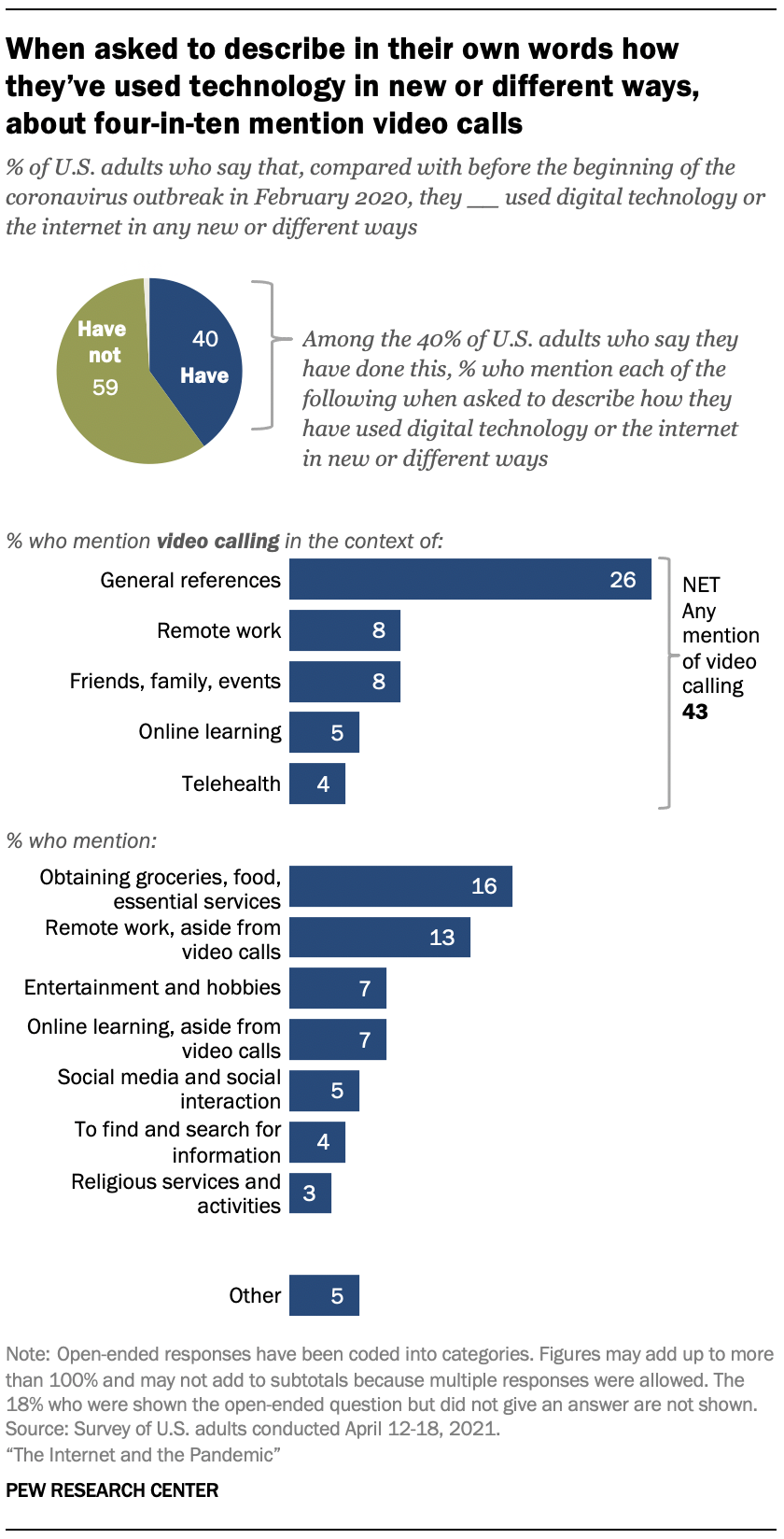

In their own words, Americans describe how they have used technology or the internet in new or different ways during the pandemic

As the severity of the pandemic grew, some Americans were faced with performing everything from their social interactions to their work or schooling online. Four-in-ten Americans say they used digital technology or the internet in new or different ways compared with before the outbreak began. Still, an even larger share – 59% – say their tech use has not changed in this way.

As is the case with digital divides in internet use and tech adoption in general, those with more formal education and higher incomes are more likely to have had new or different experiences with tech in the pandemic. For example, 56% of those with at least a bachelor’s degree say they have used technology in ways new or different to them, compared with 37% of those with some college experience and 29% of those with a high school diploma or less. Similarly, 46% of those with higher household incomes say so, compared with a smaller share of those with lower (38%) or middle incomes (40%).

Women are also more likely than men to say they have used digital technology or the internet in new and different ways (43% vs. 36%), as are adults under 50 (46%) compared with those who are 50 and older (33%).

When asked to describe what these new and different ways are, 43% mention encountering at least one form of video calls or conferences new to them in the pandemic. From weddings to funerals, church meetings to calls with family, some of these adults report their lives moved largely onto video platforms:

“We now hold bi-weekly family meetings on Zoom to make sure we are all doing okay. Before we just had individual phone calls with family members. We used Vimeo for my mother’s funeral so people could watch her funeral mass. She died of COVID-19. I used Zoom for work meetings.” – Woman, 57

“[I have had] Zoom meetings [and] Microsoft Teams meetings. [I’ve had] increased FaceTime family meetings. [I had] job interviews via the internet.” – Man, 46

“[I have been] teaching writing classes over Zoom [and I] dated someone over FaceTime for 3 months. [I] attended various online events.” – Woman, 24

While about a quarter of Americans who have used tech in new ways mention video calls generally, roughly one-in-ten (8%) referenced the remote work aspect of video conferencing specifically:

“Most of my work-related meetings are no longer in-person, but on Zoom or Teams. Instead of attending professional conferences in person, all of them are now virtual meetings. It took a bit to get comfortable with such drastic change.” – Man, 63

A similar share (8%) talk about using video calling to connect with family and friends, or attend social events or “video holidays”:

“It has opened me up to using video chat to connect with physically distanced friends. I have people that I used to only see on Facebook or in person two times a year but now we do a group video chat once a month and I am closer to them than ever.” – Woman, 39

Smaller shares discuss the move to online learning and the use of video platforms (5%) or using video calls for telehealth (4%):

“[I] had to learn how to use Google Classroom to help my son with his hybrid learning. I also did my first tele-visit with my GP doctor and I am disabled so it turns out I’ll be able to continue to use that technology once the pandemic is over to make it easier! … Not to mention, I’ve attended various social gatherings that, due to my disability, I wouldn’t have been able to attend under normal circumstances!” – Man, 28

Aside from video calls, 16% of Americans said they have used technology or the internet to obtain groceries, food or other essentials, or to perform services like banking or document signing:

“Shopping (especially groceries and home supplies) online through various different places, permanently eliminating the need to physically go to the grocery store for most shopping activities.” – Man, 42

“Ordering groceries, ordering tags for my car, doctor’s appointments, paying insurance premiums, paying bills and keeping in touch with family and friends.” – Woman, 78

In addition to those who mention remote work and online learning in the context of video calls, another 13% mention using technology in new ways for remote work and another 7% for online learning:

“Before the outbreak, I was the typical pen and paper type of middle school math teacher. After the outbreak, I have become a much more proficient virtual math teacher who has embraced many new platforms [that] have made my job easier. I have recently become fully vaccinated and returned to the brick and mortar school environment, but will maintain many of the new skills which I learned virtually.” – Man, 62

“We needed to get the internet for our granddaughter to be able to get her education while she’s home during the pandemic.” – Woman, 53

Others specifically note how they are now relying on the strength or quality of their connection in a new way:

“I upgraded my internet (was just using a hotspot previously) and for my work, I am connected all day through the workday. If the internet goes down, my ability to work at home decreases significantly. Before the work from home started, if I lost the ability to connect to the internet, it only affected me in terms of annoyance at not being able to surf the net.” – Woman, 50

Finally, other Americans have used social media and other technology for entertainment (7%), to keep up social interaction, especially on social media (5%), to find and search for information (4%), or attend online religious services or activities (3%). And their use of these digital technologies has sometimes changed over the course of the pandemic.

“I never really used Twitter before. Now I follow some important public health figures and medical doctors who are working for the CDC, etc., so I can be informed on what is going on with COVID-19 and treatment options.” – Woman, 53

“Pre-COVID-19 and even well into the pandemic, I was using the internet/my smartphone to spend countless hours on social media. Somewhere in there I deleted most of the social media apps from my phone and have been using it to read e-books and plan creative projects, mostly home improvements.” – Woman, 34

“I now attend church services online rather than in person, which I had not done before the outbreak.” – Man, 36

68% of Americans say digital interactions have been useful – but not a replacement for in-person connection

In late March 2020, as stay-at home orders upended American life, a Center survey asked U.S. adults to speculate on whether digital interactions – that is, everyday interactions that might have to be done online or by telephone because of recommended limits on social contact during the coronavirus outbreak – would be suitable replacement for in-person contact. At the time, about a quarter of Americans said digital encounters would be just as good (27%), and 8% believed that they wouldn’t be of much help. Some 64% said they would be useful, but not a replacement.

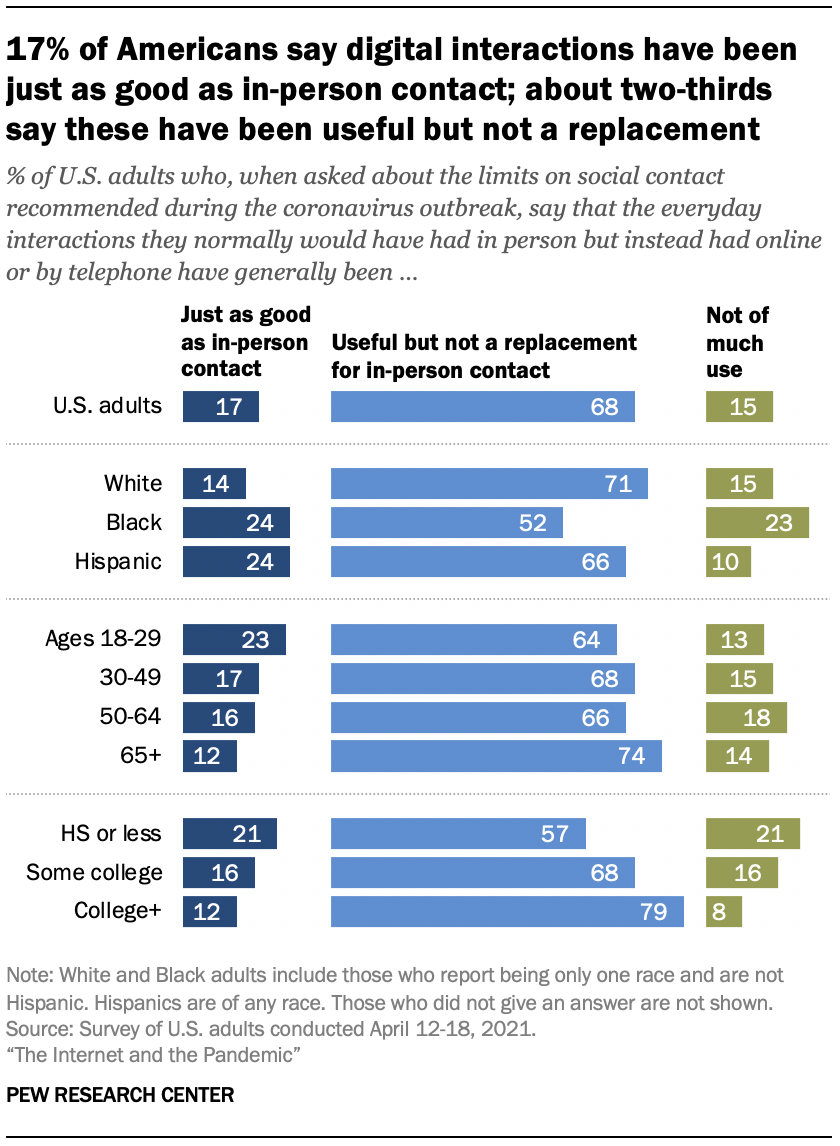

In this new survey, Americans were asked to assess how digital encounters used to replace social contact have actually gone. When asked to think about everyday interactions that happened online or by telephone rather than in person, 17% say that these have been just as good as in-person contact. In line with Americans’ own expectations a year ago, the majority of Americans – 68% – say that interactions that have moved online or to the phone have been useful, but not a replacement for in-person. Some 15% say these interactions haven’t been of much use.

Considering the more recent findings about people’s experiences, relatively small shares across demographic groups say these types of digital interactions have been just as good as in-person contact. Still, there are some small differences by race and ethnicity, age and formal educational attainment in this respect. Adults ages 18 to 29 were more skeptical than older adults in March 2020 – 21% said these interactions would be just as good as in-person contact, compared with a somewhat larger share (29%) of Americans 65 and older. In the new survey, some 23% of adults ages 18 to 29 say these interactions have been just as good as in-person contact, while a smaller share (12%) of those 65 and older who feel this way about the utility of their digital interactions.

In March 2020, Black adults were more likely than White adults to think digital interactions would be just as good as in-person contact. Black and Hispanic adults are also more likely than White adults to say these interactions have been just as good in the new survey. At the same time, about another quarter of Black adults say that these digital interactions have not been of much use. Smaller shares of White and Hispanic adults say the same.

Both then and now, how useful Americans say these interactions have been also varies by educational attainment.

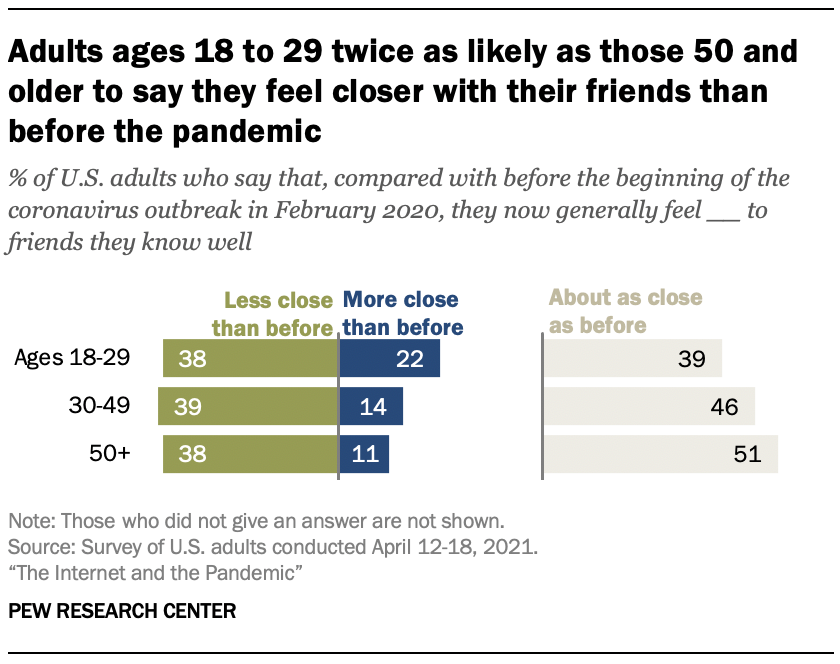

A quarter of Americans feel less close to close family members than before pandemic; about four-in-ten say the same about friends they know well

Some accounts of the pandemic have lamented the potential loss of casual friendships and acquaintances as COVID-19 narrowed people’s social circles and family structures into smaller bubbles. At the same time, some living with friends or family members may have faced increased time spent together as stay-at-home orders were imposed to combat COVID-19. Others living alone faced possible challenges of staying in touch with those close to them.

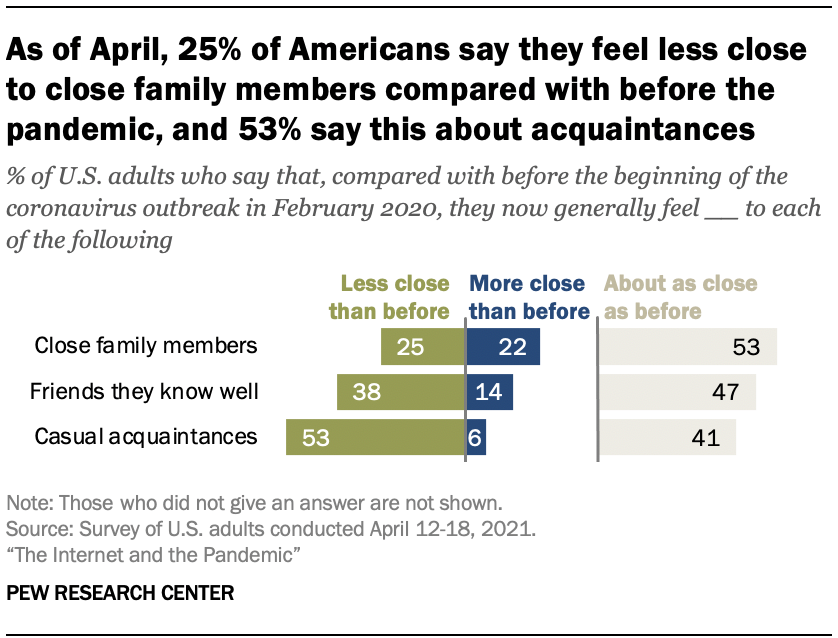

The new survey reveals that some people feel their social relationships and their connections to those in their personal networks have been in flux during the pandemic. About half of Americans (53%) say they feel less close to casual acquaintances compared with before the beginning of the coronavirus outbreak in February 2020. Some 38% say the same about friends they know well. And a quarter of Americans say they now feel less close to close family members.

At the same time, about one fifth of adults (22%) say they feel more close to close family members than they did before the pandemic. Smaller shares say this about friends they know well and casual acquaintances.

And despite the pandemic upheaval, about half say their relationships with close family members (53%) and friends they know well (47%) have stayed about as close as before, while roughly four-in-ten (41%) say this about casual acquaintances.

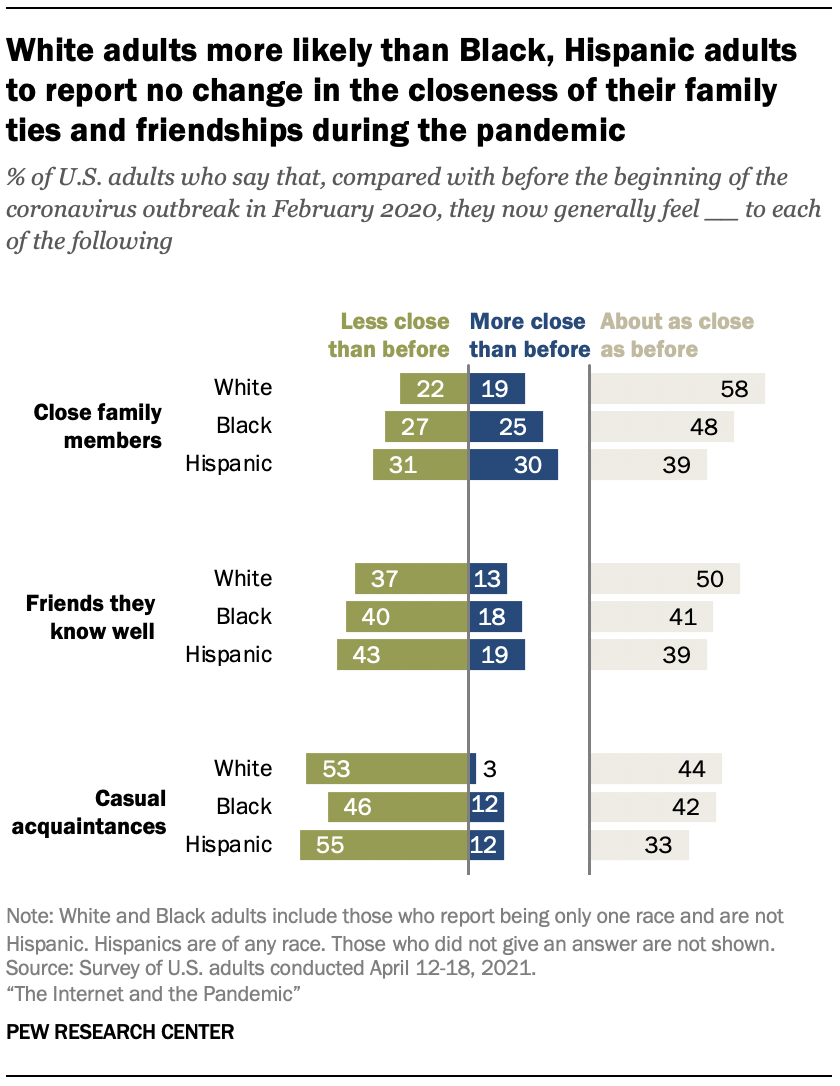

Some groups are more likely to report change in the closeness of their relationships than others. Hispanic and Black adults are less likely than White adults to say the closeness of their relationships with close family and friends has stayed about the same compared with before the beginning of the pandemic.

When it comes to close family members, similar shares of Hispanic adults say these relationships feel closer than before (30%) and less close than before (31%). Compared with White adults, they are also more likely to say they feel closer to close family, and friends they know well.

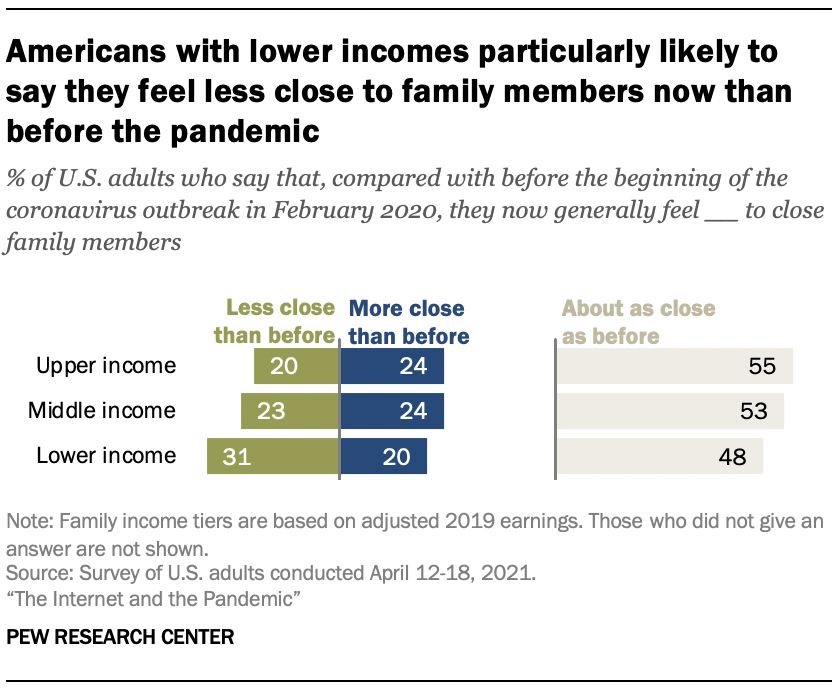

Americans with lower incomes are also more likely than others to say they feel less close to close family members compared with before the beginning of the coronavirus outbreak. About three-in-ten of those with lower incomes say so. At the same time, a fifth of Americans with lower incomes say they feel more close to close family, and 48% say they feel about as close to these family members as before the pandemic.

There is little difference in how Americans in various age groups describe the pandemic’s impact on closeness of their family relationships. But when it comes to friends they know well, young adults ages 18 to 29 are more likely to say they now feel closer to these friends than those in any other age group. Still, only about a fifth (22%) of young adults say so.

Finally, small shares of adults across gender, racial and ethnic, age and income groups say they feel closer to casual acquaintances than they did before – no more than about one-in-ten across any of these groups. In each case, far larger shares say they feel less close now.

Women are slightly more likely than men to say they feel less close to acquaintances, as are Americans with lower incomes compared with those in the upper-income tier. Those who live in urban (57%) or suburban (54%) areas are more likely to say their relationships with casual acquaintances are less close now, compared with those who live in rural areas (46%).

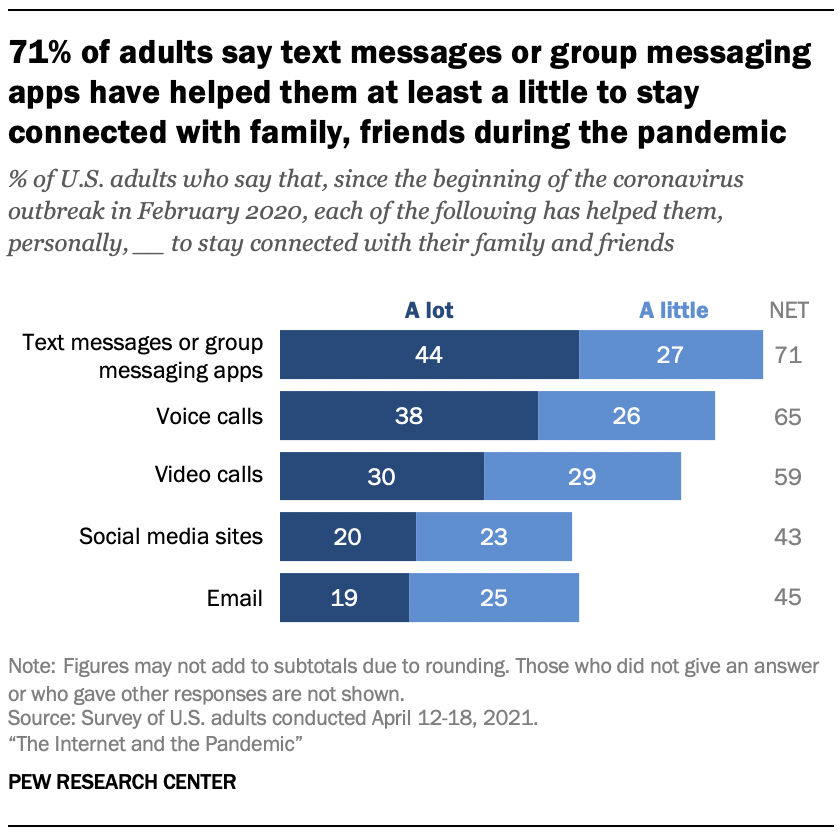

Majorities say texts or group messaging apps, voice and video calls have helped them at least a little to stay connected to family and friends

For some, technology became a way to stay in touch with others whom they could not visit in person since the pandemic began. About seven-in-ten Americans say text messages or group messaging apps have helped them personally to stay connected with their family and friends at least a little. Roughly six-in-ten or more say the same about voice (65%) and video calls (59%). Smaller shares say this about social media sites or email.

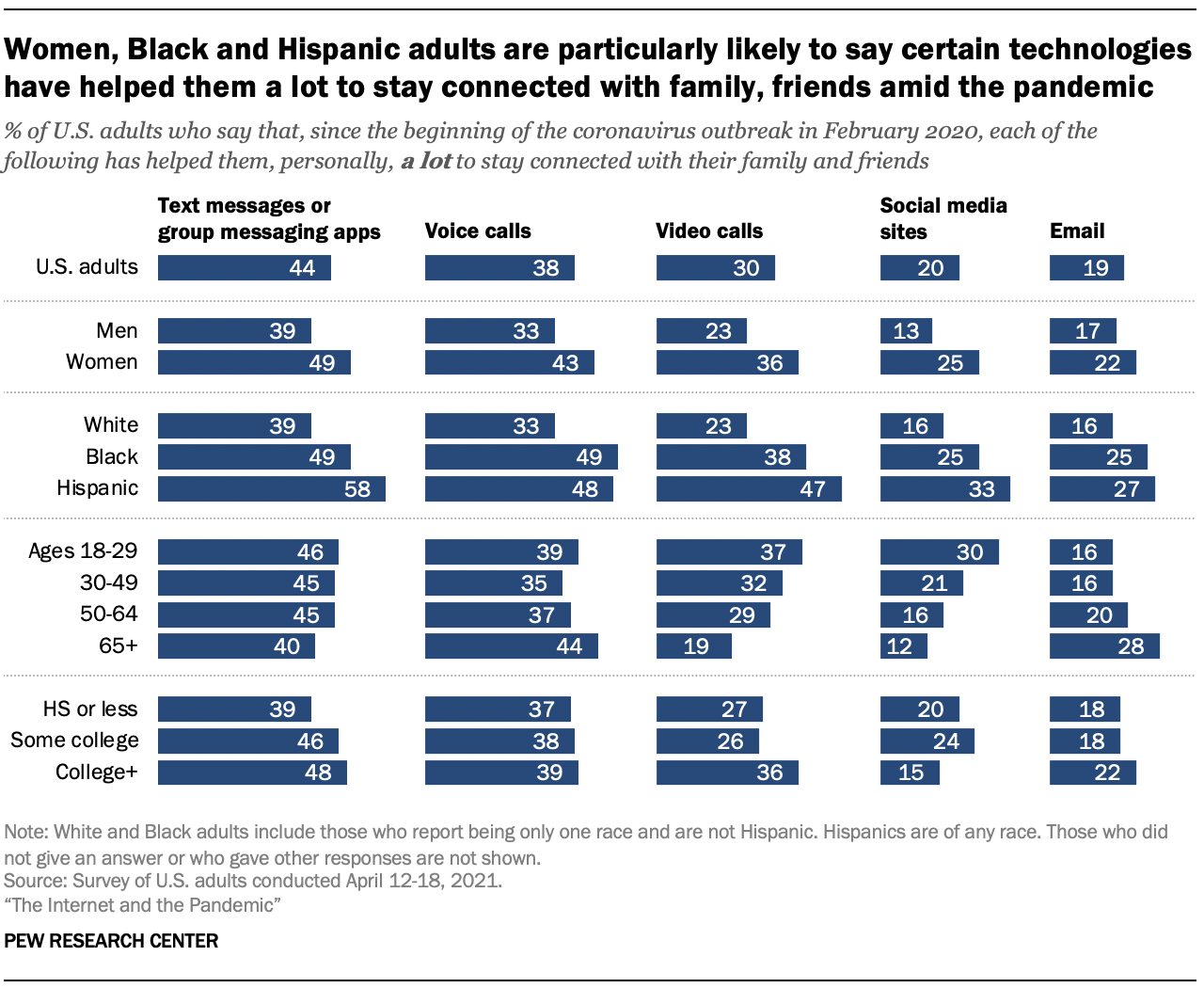

Americans’ reliance on technology early in the pandemic was apparent in several ways, from using technology to communicate with others to hosting virtual gatherings. Over a year into the pandemic, results from the new survey show that key communications platforms have been more likely to be helpful for some groups than others.

For each of the five technologies asked about in the survey, Black and Hispanic adults are more likely than White adults to say these technologies have helped them a lot to stay connected. For example, 58% of Hispanic adults say that text messages or group messaging apps have helped them a lot, personally, to stay connected with their family and friends. Some 49% of Black adults and a smaller share (39%) of White adults say the same. Voice calls have helped about half of Black and Hispanic adults a lot to stay in touch, compared with a third of White adults. Similar patterns hold for video calls, social media sites and email.

There are also differences by gender, with women being more likely than men to say that each of these technologies have helped them a lot to stay connected to friends and family.

Adults ages 18 to 29 are more likely than those 65 and older to say video calls and social media sites have helped a lot in staying connected with family and friends.

The reverse is true for email: Some 28% of Americans 65 and older say that this has helped them a lot to stay in touch, compared with smaller shares of younger Americans. Those 65 and older are also more likely than those 30 to 64 to say voice calls have helped a lot.

Other technologies – for example, text messages or group messaging apps – have been similarly helpful for Americans across age groups. Across age groups, four-in-ten or more Americans say these have helped a lot with staying in touch.

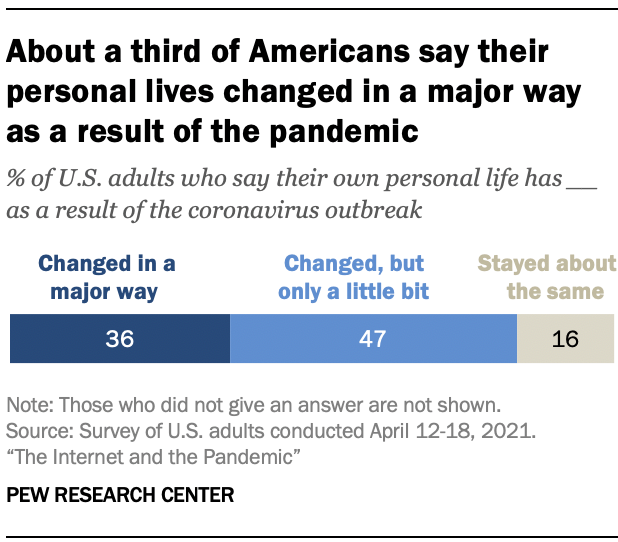

36% of Americans say their personal lives changed in a major way

As context for this exploration of how people’s technology use and experiences were affected by the pandemic, the survey also asked Americans about the overall impact of the pandemic on their personal lives.

Some 36% of Americans say their own personal life has changed in a major way as a result of the coronavirus outbreak. Another 47% say their personal life has changed, but only a little bit. And 16% say that it has stayed about the same as it was before the outbreak.

Women are somewhat more likely than men to say life has changed in a major way (39% vs. 33%), as are those with a bachelor’s or advanced degree (40%) compared with those with some college (35%) or a high school diploma or less formal education (34%). And Americans living in urban (41%) and suburban areas (37%) are more likely to say this than those living in rural areas (30%).

About half of those who say their personal lives have changed in a major way (52%) say they have used technology in new ways during the pandemic, compared with 38% of those who say their personal lives have changed a little bit and 19% of those who say life stayed about the same. At the same time, roughly seven-in-ten Americans reporting major changes in life (73%) or with more modest levels of change (69%) say digital interactions have been useful, but not a replacement for in-person interactions, compared with a smaller share among those who say their personal lives stayed about the same (52%).

Those who say their lives stayed about the same are also more likely than others to say interactions they have had online or by phone instead of in person haven’t been of much use: 26% of these adults think these virtual interactions haven’t been useful, compared with smaller shares of those who say their personal lives changed a little bit (14%) or in a major way (11%).

At the same time, those who say their lives have changed in a major way are more likely to say each of the five technologies asked about in the survey helped a lot to keep them connected, compared with those who say their lives have changed a little or stayed about the same.

Among those who said their personal lives have changed in a major way, the shares who say text messages or group messaging apps, video calls or voice calls have helped a lot are roughly 20 points higher compared with those who say their lives stayed about the same. About half or more of those who say their personal lives have changed in a major way say text messages or group messaging apps (55%) or voice calls (49%) helped them a lot to stay connected with family and friends, and 40% say the same about video calls.

Those who say their lives have changed in a major way are also more likely to say they now feel less close to close family members (35%) than those whose lives changed only a little (22%) or stayed about the same (9%). And about half (53%) of those with major change in this aspect of their life say their relationships with friends they know well are now less close.

The diminishing closeness of casual relationships is especially prominent for those whose personal lives COVID-19 changed profoundly – roughly seven-in-ten (69%) of adults with major change say that they now generally feel less close to casual acquaintances. By comparison, about a quarter (26%) of those whose personal lives stayed about the same say they feel less close to these acquaintances now.

40% of those who have used video calling during the pandemic feel worn out from such calls at least sometimes

As some Americans intensified their tech use and tried new online activities, there was a possibility that some might become “worn out” by this screen time – leading to a phenomenon commonly known as “Zoom fatigue” in the context of personal and work-related video calls. Some accounts of the pandemic also raised the question of whether Americans would try to purposefully “unplug” or otherwise manage their screen time, as many children and adults alike spent more time on their devices.

Overall, among those who have used video calling during the pandemic, four-in-ten say they have often (13%) or sometimes (27%) felt worn out or fatigued from spending time on these calls. Looking at the population overall, one-third of all adults say that they feel worn out or fatigued from video calls often (11%) or sometimes (22%).

Reported fatigue increases with greater time spent on video calls. Fully 74% of those who have used video calling several times a day during the pandemic say this is the case at least sometimes, including 36% who say they feel worn out or fatigued often. About half or more of those who are on calls less often than this, but at least a few times a week, say the same.

But even a portion of those who rarely use video calling report fatigue. About a quarter of those who have talked with others via video calls only every few weeks during the pandemic say they feel worn out at least sometimes.

The new survey shows that among those who’ve made video calls in the pandemic, there are differences in reported video call fatigue by age, formal educational attainment, and work-from-home status.

Among those who have made video calls, about six-in-ten of those ages 18 to 29 say they feel worn out or fatigued from these calls at least sometimes. By comparison, 21% of those 65 and older say so. And about half of those with a bachelor’s or advanced degree report feeling this way at least sometimes, compared with 31% of those with a high school diploma or less.

Among pandemic video call users who work from home all or most of the time, some 65% say they feel worn out or fatigued at least sometimes from the time they spend on video calls. (A separate Center study conducted in October 2020 that used a different definition of remote work and call fatigue found that about four-in-ten teleworkers who used video conferencing often were worn out by the time spent on them, compared with 63% of that group who said they were generally fine with the amount of time spent on video calls.)

As many daily activities moved online, Americans’ reactions to increased screen time were not just limited to issues related to video calling. A third of adults also say in this survey that they have tried to cut back on the amount of time they were spending with screens – specifically on the internet or their smartphone – since the beginning of the coronavirus outbreak.

Fully 49% of adults ages 18 to 29 have tried to cut back on their screen time, compared with roughly four-in-ten of those ages 30 to 49. Smaller but notable shares of those 50 to 64 (27%) and 65 and older (19%) say they’ve tried cutting down.

And Americans who use social media are more likely to say they’ve tried to cut back on screen time than those who don’t – an 8 percentage point gap.

Screen time issues also became paramount for families and children during the pandemic. The next chapter of this report discusses parents’ views on their children’s screen time, alongside other findings on the experiences of parents and children during the pandemic.