This report is based on the findings of a Pew Research Center survey on Americans’ use of the Internet. The results in this report are based on data from telephone interviews conducted by Princeton Survey Research Associates International from August 7 to September 16, 2013, among a sample of 1,801 adults, age 18 and older. Telephone interviews were conducted in English and Spanish by landline (901) and cell phone (900, including 482 without a landline phone). For results based on the total sample, one can say with 95% confidence that the error attributable to sampling is plus or minus 2.6 percentage points. For results based on Internet users (n=1,445), the margin of sampling error is plus or minus 2.9 percentage points, and for those on Facebook or Twitter (n=1,076), plus or minus 3.3 points. In addition to sampling error, question wording and practical difficulties in conducting telephone surveys may introduce some error or bias into the findings of opinion polls.

A combination of landline and cellular random digit dial (RDD) samples was used to represent all adults in the United States who have access to either a landline or cellular telephone. Both samples were provided by Survey Sampling International, LLC (SSI) according to PSRAI specifications. Numbers for the landline sample were drawn with equal probabilities from active blocks (area code + exchange + two-digit block number) that contained three or more residential directory listings. The cellular sample was not list-assisted, but was drawn through a systematic sampling from dedicated wireless 100-blocks and shared service 100-blocks with no directory-listed landline numbers.

New sample was released daily and was kept in the field for at least seven days. The sample was released in replicates, which are representative subsamples of the larger population. This ensures that complete call procedures were followed for the entire sample. At least 7 attempts were made to complete an interview at a sampled telephone number. The calls were staggered over times of day and days of the week to maximize the chances of making contact with a potential respondent. Each number received at least one daytime call in an attempt to find someone available. For the landline sample, interviewers asked to speak with the youngest adult male or female currently at home based on a random rotation. If no male/female was available, interviewers asked to speak with the youngest adult of the other gender. For the cellular sample, interviews were conducted with the person who answered the phone. Interviewers verified that the person was an adult and in a safe place before administering the survey. Cellular sample respondents were offered a post-paid cash incentive for their participation. All interviews completed on any given day were considered to be the final sample for that day.

Weighting is generally used in survey analysis to compensate for sample designs and patterns of non-response that might bias results. A two-stage weighting procedure was used to weight this dual-frame sample. The first-stage corrected for different probabilities of selection associated with the number of adults in each household and each respondent’s telephone usage patterns. This weighting also adjusts for the overlapping landline and cell sample frames and the relative sizes of each frame and each sample.

The second stage of weighting balances sample demographics to population parameters. The sample is balanced to match national population parameters for sex, age, education, race, Hispanic origin, region (U.S. Census definitions), population density, and telephone usage. The Hispanic origin was split out based on nativity; U.S born and non-U.S. born. The White, non-Hispanic subgroup was also balanced on age, education and region. The basic weighting parameters came from the US Census Bureau’s 2011 American Community Survey data. The population density parameter was derived from Census 2010 data. The telephone usage parameter came from an analysis of the July-December 2012 National Health Interview Survey.

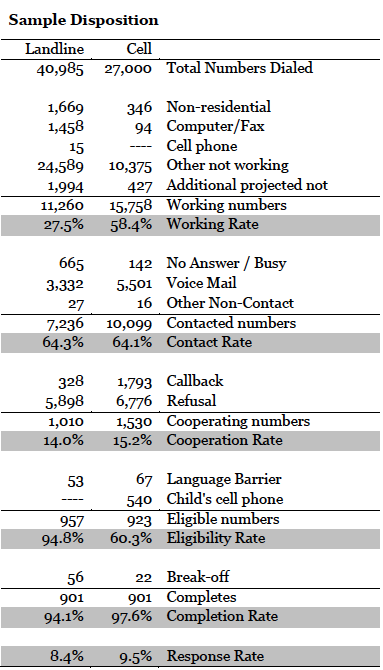

Following is the full disposition of all sampled telephone numbers:

The disposition reports all of the sampled telephone numbers ever dialed from the original telephone number samples. The response rate estimates the fraction of all eligible respondents in the sample that were ultimately interviewed. At PSRAI it is calculated by taking the product of three component rates:

Contact rate—the proportion of working numbers where a request for interview was made

Cooperation rate—the proportion of contacted numbers where a consent for interview was at least initially obtained, versus those refused

Completion rate—the proportion of initially cooperating and eligible interviews that were completed

Thus the response rate for the landline sample was 8 percent. The response rate for the cellular sample was 10 percent.

References

Boczkowski, P. and E. Mitchelstein (2013). The news gap : when the information preferences of the media and the public diverge. Cambridge, MIT Press.

Das, S. and A. Kramer (2013). “Self-censorship on Facebook.” Proc. of ICWSM 2013: 120-127.

Goel, S., W. Mason, et al. (2010). “Real and Perceived Attitude Agreement in Social Networks.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 99(4): 611-621.

Jacobs, L. R., F. L. Cook, et al. (2009). Talking Together: Public Deliberation and Political Participation in America. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Marwick, A. E. and d. boyd (2010). “I Tweet Honestly, I Tweet Passionately: Twitter Users, Context Collapse, and the Imagined Audience.” New Media & Society 13(1): 114-133.

Mitchell, A., J. Holcomb, et al. (2013). News Use across Social Media Platforms. Washingtown, Pew Research Center.

Noelle-Neumann, E. (1974). “The Spiral of Silence A Theory of Public Opinion.” Journal of Communication 24(2): 43-51.

Oshagan, H. (1996). “Reference Group Influince on Public Expression.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 8(4): 335-354.

Sunstein, C. R. (2001). Republic.com. Princeton, N.J., Princeton University Press.

Wyatt, R. O., E. Katz, et al. (2000). “Bridging the Spheres: Political and Personal Conversation in Public and Private Spaces.” Journal of Communication 50(1): 71-92.