h3>39% of U.S. adults are caregiversh3>39% of U.S. adults are caregivers

Bathing and dressing someone who needs help, driving to doctor appointments, sorting through paperwork, making sure this pill is taken with breakfast and that pill at bedtime—these hands-on, caregiving activities define the word “offline.”

Yet, these days, caregivers are health information specialists. They have the safety, comfort, and even the life of a loved one in their hands. They are asked to perform a dizzying array of medical and personal tasks outside clinical settings and the stakes are very high.[4. numoffset="4" “Home Alone: Family Caregivers Providing Complex Chronic Care,” by Susan C. Reinhard, Carol Levine, and Sarah Samis. (AARP Public Public Policy Institute and the United Hospital Fund: October 2012). Available at: http://www.aarp.org/home-family/caregiving/info-10-2012/home-alone-family-caregivers-providing-complex-chronic-care.html] Caregivers display what we at the Pew Research Center have identified as a core social impact of the internet: the ability to quickly gather information on a complex topic to make decisions.

This national survey by the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project, supported by the California HealthCare Foundation, finds that caregivers are highly likely to gather advice from clinicians, family, friends, and peers; to track their own and their loved ones’ health data; and to use the internet to research health conditions and treatments.

We find that being a caregiver is a special factor highly correlated with certain kinds of online information seeking. When controlling for age, income, education, ethnicity, and good overall health, caregivers are more likely than other internet users to:

- Gather health information online, particularly about medical problems, treatments, and drugs.

- Go online specifically to try to figure out what condition they or someone else might have.

- Consult online reviews about drugs and other treatments.

- Track their weight, diet, or exercise routine.

- Read online about someone else’s personal health experience.

- Go online to find others with similar health concerns.

An aging population and a rise in the percentage of people living with chronic conditions means that the United States will need to increasingly rely on family caregivers to provide front-line health care. This study presents evidence about how caregivers currently gather, share, and create health information and support.

Bathing and dressing someone who needs help, driving to doctor appointments, sorting through paperwork, making sure this pill is taken with breakfast and that pill at bedtime—these hands-on, caregiving activities define the word “offline.”

Yet, these days, caregivers are health information specialists. They have the safety, comfort, and even the life of a loved one in their hands. They are asked to perform a dizzying array of medical and personal tasks outside clinical settings and the stakes are very high.[4. numoffset="4" “Home Alone: Family Caregivers Providing Complex Chronic Care,” by Susan C. Reinhard, Carol Levine, and Sarah Samis. (AARP Public Public Policy Institute and the United Hospital Fund: October 2012). Available at:

http://www.aarp.org/home-family/caregiving/info-10-2012/home-alone-family-caregivers-providing-complex-chronic-care.html] Caregivers display what we at the Pew Research Center have identified as a core social impact of the internet: the ability to quickly gather information on a complex topic to make decisions.

This national survey by the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project, supported by the California HealthCare Foundation, finds that caregivers are highly likely to gather advice from clinicians, family, friends, and peers; to track their own and their loved ones’ health data; and to use the internet to research health conditions and treatments.

We find that being a caregiver is a special factor highly correlated with certain kinds of online information seeking. When controlling for age, income, education, ethnicity, and good overall health, caregivers are more likely than other internet users to:

- Gather health information online, particularly about medical problems, treatments, and drugs.

- Go online specifically to try to figure out what condition they or someone else might have.

- Consult online reviews about drugs and other treatments.

- Track their weight, diet, or exercise routine.

- Read online about someone else’s personal health experience.

- Go online to find others with similar health concerns.

An aging population and a rise in the percentage of people living with chronic conditions means that the United States will need to increasingly rely on family caregivers to provide front-line health care. This study presents evidence about how caregivers currently gather, share, and create health information and support.

Caring for both children and adults with significant health challenges

To measure the population of U.S. adults who provide care to loved ones with significant health issues, we asked a series of questions beginning with:

In the past 12 months, have you provided unpaid care to an adult relative or friend 18 years or older to help them take care of themselves? Unpaid care may include help with personal needs or household chores. It might be managing a person’s finances, arranging for outside services, or visiting regularly to see how they are doing. This person need not live with you.

Some 36% of U.S. adults say they provided such unpaid care to an adult in the past year, up from 27% in 2010.

Those respondents were then asked:

Do you provide this type of care to just one adult, or do you care for more than one adult?

Two-thirds (66%) of that group say they care for one adult, which represents one-quarter of the U.S. population ages 18 and older. One-third (34%) of people who are helping an adult relative or friend say they care for more than one adult.

Half (47%) of those who care for adults say at least one is their parent or parent-in-law.

Separately, we asked:

In the past 12 months, have you provided unpaid care to any child under the age of 18 because of a medical, behavioral, or other condition or disability? This could include care for ongoing medical conditions or serious short-term conditions, emotional or behavioral problems, or developmental problems, including mental retardation.

Eight percent of U.S. adults say the provided unpaid care to a child living with health challenges or disabilities, up from 5% in 2010.

In sum, 39% of U.S. adults are caregivers, up from 30% in 2010.[5. numoffset="5" “Family Caregivers Online,” by Susannah Fox and Joanna Brenner. (Pew Research Center: July 12, 2012). Available at:

https://legacy.pewresearch.org/internet/Reports/2012/Caregivers-online.aspx] As the U.S. population ages and medical advances save and extend more lives, caregiving is likely to become a more common role than it has ever been before.

Who are caregivers?

Caregiving touches every segment of the population. Men and women are equally likely to be caregivers. People of all age groups provide care for loved ones, with a slightly higher percentage of those ages 30-64 saying they do so. Caregivers are more likely than other adults to be married and to be employed full time.

They are also more likely than non-caregivers to have gone through a recent health crisis or to have experienced a significant change in their physical health (including positive changes, such as quitting smoking). (See Appendix for detailed tables.)

This finding dovetails with clinical studies showing that the stress associated with caregiving has an independent, negative effect on people’s health.[6. See, for example: “Caregiver Health” (Family Caregiver Alliance). Available at:

http://www.caregiver.org/caregiver/jsp/content_node.jsp?nodeid=1822]

Bathing and dressing someone who needs help, driving to doctor appointments, sorting through paperwork, making sure this pill is taken with breakfast and that pill at bedtime—these hands-on, caregiving activities define the word “offline.”

Yet, these days, caregivers are health information specialists. They have the safety, comfort, and even the life of a loved one in their hands. They are asked to perform a dizzying array of medical and personal tasks outside clinical settings and the stakes are very high.[4. numoffset="4" “Home Alone: Family Caregivers Providing Complex Chronic Care,” by Susan C. Reinhard, Carol Levine, and Sarah Samis. (AARP Public Public Policy Institute and the United Hospital Fund: October 2012). Available at:

http://www.aarp.org/home-family/caregiving/info-10-2012/home-alone-family-caregivers-providing-complex-chronic-care.html] Caregivers display what we at the Pew Research Center have identified as a core social impact of the internet: the ability to quickly gather information on a complex topic to make decisions.

This national survey by the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project, supported by the California HealthCare Foundation, finds that caregivers are highly likely to gather advice from clinicians, family, friends, and peers; to track their own and their loved ones’ health data; and to use the internet to research health conditions and treatments.

We find that being a caregiver is a special factor highly correlated with certain kinds of online information seeking. When controlling for age, income, education, ethnicity, and good overall health, caregivers are more likely than other internet users to:

- Gather health information online, particularly about medical problems, treatments, and drugs.

- Go online specifically to try to figure out what condition they or someone else might have.

- Consult online reviews about drugs and other treatments.

- Track their weight, diet, or exercise routine.

- Read online about someone else’s personal health experience.

- Go online to find others with similar health concerns.

An aging population and a rise in the percentage of people living with chronic conditions means that the United States will need to increasingly rely on family caregivers to provide front-line health care. This study presents evidence about how caregivers currently gather, share, and create health information and support.

Caring for both children and adults with significant health challenges

To measure the population of U.S. adults who provide care to loved ones with significant health issues, we asked a series of questions beginning with:

In the past 12 months, have you provided unpaid care to an adult relative or friend 18 years or older to help them take care of themselves? Unpaid care may include help with personal needs or household chores. It might be managing a person’s finances, arranging for outside services, or visiting regularly to see how they are doing. This person need not live with you.

Some 36% of U.S. adults say they provided such unpaid care to an adult in the past year, up from 27% in 2010.

Those respondents were then asked:

Do you provide this type of care to just one adult, or do you care for more than one adult?

Two-thirds (66%) of that group say they care for one adult, which represents one-quarter of the U.S. population ages 18 and older. One-third (34%) of people who are helping an adult relative or friend say they care for more than one adult.

Half (47%) of those who care for adults say at least one is their parent or parent-in-law.

Separately, we asked:

In the past 12 months, have you provided unpaid care to any child under the age of 18 because of a medical, behavioral, or other condition or disability? This could include care for ongoing medical conditions or serious short-term conditions, emotional or behavioral problems, or developmental problems, including mental retardation.

Eight percent of U.S. adults say the provided unpaid care to a child living with health challenges or disabilities, up from 5% in 2010.

In sum, 39% of U.S. adults are caregivers, up from 30% in 2010.[5. numoffset="5" “Family Caregivers Online,” by Susannah Fox and Joanna Brenner. (Pew Research Center: July 12, 2012). Available at:

https://legacy.pewresearch.org/internet/Reports/2012/Caregivers-online.aspx] As the U.S. population ages and medical advances save and extend more lives, caregiving is likely to become a more common role than it has ever been before.

Who are caregivers?

Caregiving touches every segment of the population. Men and women are equally likely to be caregivers. People of all age groups provide care for loved ones, with a slightly higher percentage of those ages 30-64 saying they do so. Caregivers are more likely than other adults to be married and to be employed full time.

They are also more likely than non-caregivers to have gone through a recent health crisis or to have experienced a significant change in their physical health (including positive changes, such as quitting smoking). (See Appendix for detailed tables.)

This finding dovetails with clinical studies showing that the stress associated with caregiving has an independent, negative effect on people’s health.[6. See, for example: “Caregiver Health” (Family Caregiver Alliance). Available at:

http://www.caregiver.org/caregiver/jsp/content_node.jsp?nodeid=1822]

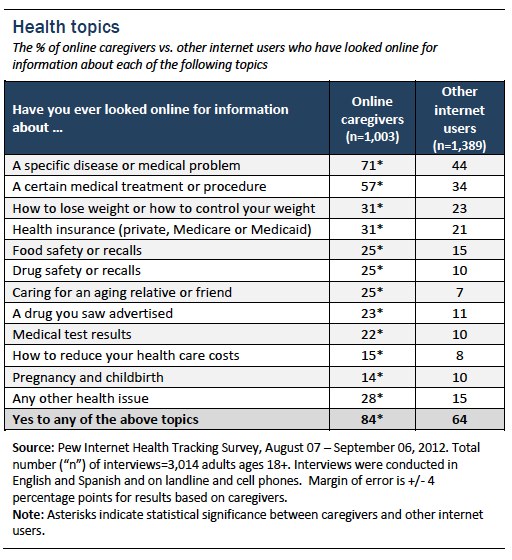

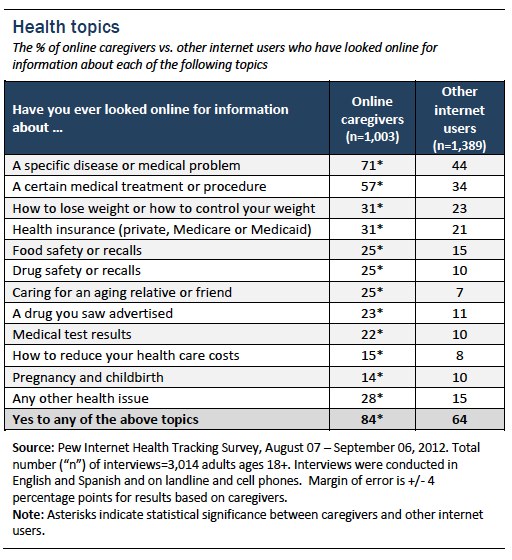

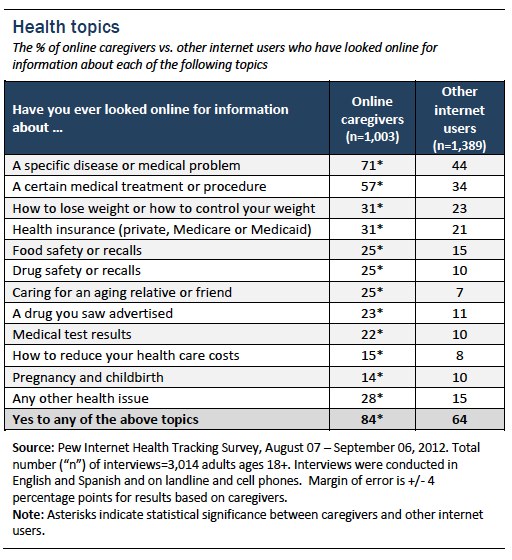

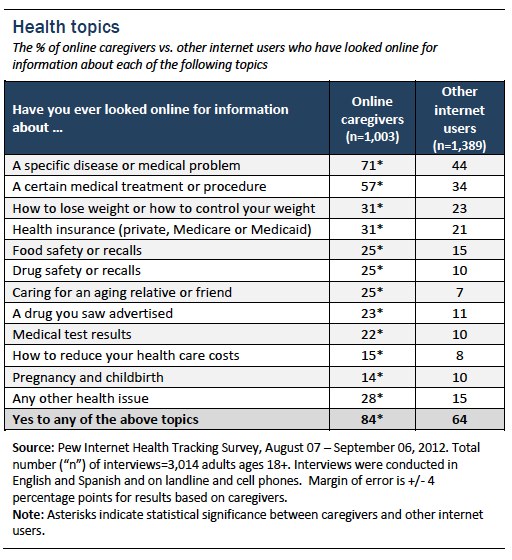

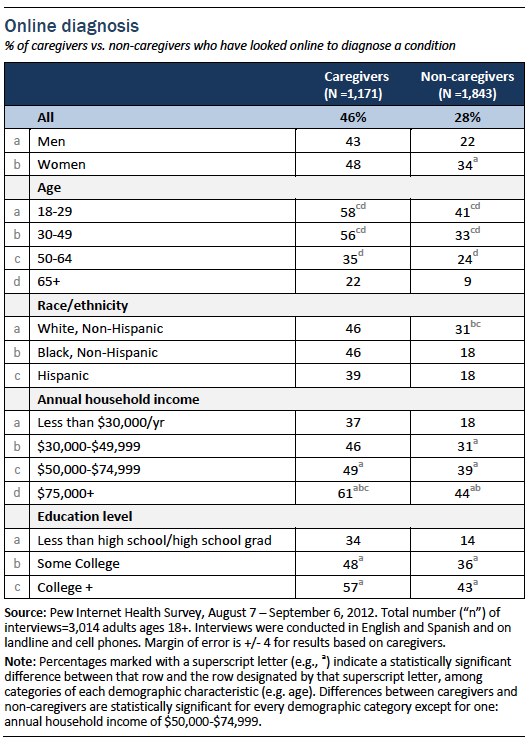

Caregivers are wide-ranging online health information consumers

Fully 86% of caregivers have internet access, compared with 78% of non-caregivers. And 84% of caregivers with internet access say they went online within the past year to research health topics such as medical procedures, health insurance, and drug safety. By comparison, 64% of non-caregivers with internet access say they did online health research in the past 12 months.

For brevity’s sake, we will refer to those who research health topics as “online health seekers.” When calculated as a percentage of all U.S. adults, not just internet users, 72% of caregivers are online health seekers, compared with 50% of non-caregivers.

When controlling for age, income, education, ethnicity, and good overall health, being a caregiver increases the probability that someone will go online to look for health information. Living in a higher income household and reporting a higher level of education also increases someone’s likelihood to do health research online. Being age 40 or older decreases the probability that someone will do this type of research online.

We tested four topics and found that these patterns held for each one, that is, being a caregiver has an independent effect on someone’s likelihood to look online for information about:

- A specific disease or medical problem

- A certain medical treatment or procedure

- Drug safety or recalls

- A drug they saw advertised

In other words, caregivers’ appetite for certain kinds of online health information is related to their home health care role, independent of other demographic factors.

Bathing and dressing someone who needs help, driving to doctor appointments, sorting through paperwork, making sure this pill is taken with breakfast and that pill at bedtime—these hands-on, caregiving activities define the word “offline.”

Yet, these days, caregivers are health information specialists. They have the safety, comfort, and even the life of a loved one in their hands. They are asked to perform a dizzying array of medical and personal tasks outside clinical settings and the stakes are very high.[4. numoffset="4" “Home Alone: Family Caregivers Providing Complex Chronic Care,” by Susan C. Reinhard, Carol Levine, and Sarah Samis. (AARP Public Public Policy Institute and the United Hospital Fund: October 2012). Available at:

http://www.aarp.org/home-family/caregiving/info-10-2012/home-alone-family-caregivers-providing-complex-chronic-care.html] Caregivers display what we at the Pew Research Center have identified as a core social impact of the internet: the ability to quickly gather information on a complex topic to make decisions.

This national survey by the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project, supported by the California HealthCare Foundation, finds that caregivers are highly likely to gather advice from clinicians, family, friends, and peers; to track their own and their loved ones’ health data; and to use the internet to research health conditions and treatments.

We find that being a caregiver is a special factor highly correlated with certain kinds of online information seeking. When controlling for age, income, education, ethnicity, and good overall health, caregivers are more likely than other internet users to:

- Gather health information online, particularly about medical problems, treatments, and drugs.

- Go online specifically to try to figure out what condition they or someone else might have.

- Consult online reviews about drugs and other treatments.

- Track their weight, diet, or exercise routine.

- Read online about someone else’s personal health experience.

- Go online to find others with similar health concerns.

An aging population and a rise in the percentage of people living with chronic conditions means that the United States will need to increasingly rely on family caregivers to provide front-line health care. This study presents evidence about how caregivers currently gather, share, and create health information and support.

Caring for both children and adults with significant health challenges

To measure the population of U.S. adults who provide care to loved ones with significant health issues, we asked a series of questions beginning with:

In the past 12 months, have you provided unpaid care to an adult relative or friend 18 years or older to help them take care of themselves? Unpaid care may include help with personal needs or household chores. It might be managing a person’s finances, arranging for outside services, or visiting regularly to see how they are doing. This person need not live with you.

Some 36% of U.S. adults say they provided such unpaid care to an adult in the past year, up from 27% in 2010.

Those respondents were then asked:

Do you provide this type of care to just one adult, or do you care for more than one adult?

Two-thirds (66%) of that group say they care for one adult, which represents one-quarter of the U.S. population ages 18 and older. One-third (34%) of people who are helping an adult relative or friend say they care for more than one adult.

Half (47%) of those who care for adults say at least one is their parent or parent-in-law.

Separately, we asked:

In the past 12 months, have you provided unpaid care to any child under the age of 18 because of a medical, behavioral, or other condition or disability? This could include care for ongoing medical conditions or serious short-term conditions, emotional or behavioral problems, or developmental problems, including mental retardation.

Eight percent of U.S. adults say the provided unpaid care to a child living with health challenges or disabilities, up from 5% in 2010.

In sum, 39% of U.S. adults are caregivers, up from 30% in 2010.[5. numoffset="5" “Family Caregivers Online,” by Susannah Fox and Joanna Brenner. (Pew Research Center: July 12, 2012). Available at:

https://legacy.pewresearch.org/internet/Reports/2012/Caregivers-online.aspx] As the U.S. population ages and medical advances save and extend more lives, caregiving is likely to become a more common role than it has ever been before.

Who are caregivers?

Caregiving touches every segment of the population. Men and women are equally likely to be caregivers. People of all age groups provide care for loved ones, with a slightly higher percentage of those ages 30-64 saying they do so. Caregivers are more likely than other adults to be married and to be employed full time.

They are also more likely than non-caregivers to have gone through a recent health crisis or to have experienced a significant change in their physical health (including positive changes, such as quitting smoking). (See Appendix for detailed tables.)

This finding dovetails with clinical studies showing that the stress associated with caregiving has an independent, negative effect on people’s health.[6. See, for example: “Caregiver Health” (Family Caregiver Alliance). Available at:

http://www.caregiver.org/caregiver/jsp/content_node.jsp?nodeid=1822]

Caregivers are wide-ranging online health information consumers

Fully 86% of caregivers have internet access, compared with 78% of non-caregivers. And 84% of caregivers with internet access say they went online within the past year to research health topics such as medical procedures, health insurance, and drug safety. By comparison, 64% of non-caregivers with internet access say they did online health research in the past 12 months.

For brevity’s sake, we will refer to those who research health topics as “online health seekers.” When calculated as a percentage of all U.S. adults, not just internet users, 72% of caregivers are online health seekers, compared with 50% of non-caregivers.

When controlling for age, income, education, ethnicity, and good overall health, being a caregiver increases the probability that someone will go online to look for health information. Living in a higher income household and reporting a higher level of education also increases someone’s likelihood to do health research online. Being age 40 or older decreases the probability that someone will do this type of research online.

We tested four topics and found that these patterns held for each one, that is, being a caregiver has an independent effect on someone’s likelihood to look online for information about:

- A specific disease or medical problem

- A certain medical treatment or procedure

- Drug safety or recalls

- A drug they saw advertised

In other words, caregivers’ appetite for certain kinds of online health information is related to their home health care role, independent of other demographic factors.

Most caregivers say the internet has been helpful to them

When asked if online resources are helpful:

- 59% of caregivers with internet access say that online resources have been helpful to their ability to provide care and support for the person in their care.

- 52% of caregivers with internet access say that online resources have been helpful to their ability to cope with the stress of being a caregiver.

Younger caregivers are more likely than older ones to report that the internet has been helpful to their ability to provide care and support: 70% of caregivers ages 18-29 say that, compared with 51% of those ages 50-64 years old. Two-thirds of male caregivers say the internet has been helpful in this way, compared with 55% of female caregivers.

Younger caregivers are also more likely than older ones to say the internet has been helpful in coping with related stress: 70% of caregivers ages 18-29 say that, compared with 43% of those ages 50-64 years old. There was no difference between men and women on this question, nor were there any other notable demographic differences.

Bathing and dressing someone who needs help, driving to doctor appointments, sorting through paperwork, making sure this pill is taken with breakfast and that pill at bedtime—these hands-on, caregiving activities define the word “offline.”

Yet, these days, caregivers are health information specialists. They have the safety, comfort, and even the life of a loved one in their hands. They are asked to perform a dizzying array of medical and personal tasks outside clinical settings and the stakes are very high.[4. numoffset="4" “Home Alone: Family Caregivers Providing Complex Chronic Care,” by Susan C. Reinhard, Carol Levine, and Sarah Samis. (AARP Public Public Policy Institute and the United Hospital Fund: October 2012). Available at:

http://www.aarp.org/home-family/caregiving/info-10-2012/home-alone-family-caregivers-providing-complex-chronic-care.html] Caregivers display what we at the Pew Research Center have identified as a core social impact of the internet: the ability to quickly gather information on a complex topic to make decisions.

This national survey by the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project, supported by the California HealthCare Foundation, finds that caregivers are highly likely to gather advice from clinicians, family, friends, and peers; to track their own and their loved ones’ health data; and to use the internet to research health conditions and treatments.

We find that being a caregiver is a special factor highly correlated with certain kinds of online information seeking. When controlling for age, income, education, ethnicity, and good overall health, caregivers are more likely than other internet users to:

- Gather health information online, particularly about medical problems, treatments, and drugs.

- Go online specifically to try to figure out what condition they or someone else might have.

- Consult online reviews about drugs and other treatments.

- Track their weight, diet, or exercise routine.

- Read online about someone else’s personal health experience.

- Go online to find others with similar health concerns.

An aging population and a rise in the percentage of people living with chronic conditions means that the United States will need to increasingly rely on family caregivers to provide front-line health care. This study presents evidence about how caregivers currently gather, share, and create health information and support.

Caring for both children and adults with significant health challenges

To measure the population of U.S. adults who provide care to loved ones with significant health issues, we asked a series of questions beginning with:

In the past 12 months, have you provided unpaid care to an adult relative or friend 18 years or older to help them take care of themselves? Unpaid care may include help with personal needs or household chores. It might be managing a person’s finances, arranging for outside services, or visiting regularly to see how they are doing. This person need not live with you.

Some 36% of U.S. adults say they provided such unpaid care to an adult in the past year, up from 27% in 2010.

Those respondents were then asked:

Do you provide this type of care to just one adult, or do you care for more than one adult?

Two-thirds (66%) of that group say they care for one adult, which represents one-quarter of the U.S. population ages 18 and older. One-third (34%) of people who are helping an adult relative or friend say they care for more than one adult.

Half (47%) of those who care for adults say at least one is their parent or parent-in-law.

Separately, we asked:

In the past 12 months, have you provided unpaid care to any child under the age of 18 because of a medical, behavioral, or other condition or disability? This could include care for ongoing medical conditions or serious short-term conditions, emotional or behavioral problems, or developmental problems, including mental retardation.

Eight percent of U.S. adults say the provided unpaid care to a child living with health challenges or disabilities, up from 5% in 2010.

In sum, 39% of U.S. adults are caregivers, up from 30% in 2010.[5. numoffset="5" “Family Caregivers Online,” by Susannah Fox and Joanna Brenner. (Pew Research Center: July 12, 2012). Available at:

https://legacy.pewresearch.org/internet/Reports/2012/Caregivers-online.aspx] As the U.S. population ages and medical advances save and extend more lives, caregiving is likely to become a more common role than it has ever been before.

Who are caregivers?

Caregiving touches every segment of the population. Men and women are equally likely to be caregivers. People of all age groups provide care for loved ones, with a slightly higher percentage of those ages 30-64 saying they do so. Caregivers are more likely than other adults to be married and to be employed full time.

They are also more likely than non-caregivers to have gone through a recent health crisis or to have experienced a significant change in their physical health (including positive changes, such as quitting smoking). (See Appendix for detailed tables.)

This finding dovetails with clinical studies showing that the stress associated with caregiving has an independent, negative effect on people’s health.[6. See, for example: “Caregiver Health” (Family Caregiver Alliance). Available at:

http://www.caregiver.org/caregiver/jsp/content_node.jsp?nodeid=1822]

Caregivers are wide-ranging online health information consumers

Fully 86% of caregivers have internet access, compared with 78% of non-caregivers. And 84% of caregivers with internet access say they went online within the past year to research health topics such as medical procedures, health insurance, and drug safety. By comparison, 64% of non-caregivers with internet access say they did online health research in the past 12 months.

For brevity’s sake, we will refer to those who research health topics as “online health seekers.” When calculated as a percentage of all U.S. adults, not just internet users, 72% of caregivers are online health seekers, compared with 50% of non-caregivers.

When controlling for age, income, education, ethnicity, and good overall health, being a caregiver increases the probability that someone will go online to look for health information. Living in a higher income household and reporting a higher level of education also increases someone’s likelihood to do health research online. Being age 40 or older decreases the probability that someone will do this type of research online.

We tested four topics and found that these patterns held for each one, that is, being a caregiver has an independent effect on someone’s likelihood to look online for information about:

- A specific disease or medical problem

- A certain medical treatment or procedure

- Drug safety or recalls

- A drug they saw advertised

In other words, caregivers’ appetite for certain kinds of online health information is related to their home health care role, independent of other demographic factors.

Most caregivers say the internet has been helpful to them

When asked if online resources are helpful:

- 59% of caregivers with internet access say that online resources have been helpful to their ability to provide care and support for the person in their care.

- 52% of caregivers with internet access say that online resources have been helpful to their ability to cope with the stress of being a caregiver.

Younger caregivers are more likely than older ones to report that the internet has been helpful to their ability to provide care and support: 70% of caregivers ages 18-29 say that, compared with 51% of those ages 50-64 years old. Two-thirds of male caregivers say the internet has been helpful in this way, compared with 55% of female caregivers.

Younger caregivers are also more likely than older ones to say the internet has been helpful in coping with related stress: 70% of caregivers ages 18-29 say that, compared with 43% of those ages 50-64 years old. There was no difference between men and women on this question, nor were there any other notable demographic differences.

Eight in ten online health inquiries start at a search engine

When asked to think about the last time they searched online for health information, 79% of caregivers who are online health seekers say they started at a search engine such as Google, Bing, or Yahoo. Fourteen percent started at a site that specializes in health information, such as WebMD. Just 1% say they started at a more general site like Wikipedia and another 1% started at a social networking site like Facebook. There are no significant differences between caregivers and non-caregivers when it comes to starting an online health inquiry at a search engine, specialized health website, or other site.

Overall, this matches what we found in our first health survey more than a decade ago. Then, as now, eight in ten online health seekers are likely to start at a general search engine when looking online for health or medical information.

Caregivers are likely to say their last health search was on behalf of someone else

Caring for others’ information needs is a common activity among all internet users. Half of all health searches are conducted on behalf of someone else. This long-standing pattern, measured in our first health survey in the year 2000, is particularly pronounced among caregivers: 63% say their last search was at least in part on behalf of someone else, compared with 47% of non-caregiver online health seekers.

Nearly half of all caregivers have gone online to try to figure out a possible health diagnosish3>39% of U.S. adults are caregivers

Bathing and dressing someone who needs help, driving to doctor appointments, sorting through paperwork, making sure this pill is taken with breakfast and that pill at bedtime—these hands-on, caregiving activities define the word “offline.”

Yet, these days, caregivers are health information specialists. They have the safety, comfort, and even the life of a loved one in their hands. They are asked to perform a dizzying array of medical and personal tasks outside clinical settings and the stakes are very high.[4. numoffset="4" “Home Alone: Family Caregivers Providing Complex Chronic Care,” by Susan C. Reinhard, Carol Levine, and Sarah Samis. (AARP Public Public Policy Institute and the United Hospital Fund: October 2012). Available at:

http://www.aarp.org/home-family/caregiving/info-10-2012/home-alone-family-caregivers-providing-complex-chronic-care.html] Caregivers display what we at the Pew Research Center have identified as a core social impact of the internet: the ability to quickly gather information on a complex topic to make decisions.

This national survey by the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project, supported by the California HealthCare Foundation, finds that caregivers are highly likely to gather advice from clinicians, family, friends, and peers; to track their own and their loved ones’ health data; and to use the internet to research health conditions and treatments.

We find that being a caregiver is a special factor highly correlated with certain kinds of online information seeking. When controlling for age, income, education, ethnicity, and good overall health, caregivers are more likely than other internet users to:

- Gather health information online, particularly about medical problems, treatments, and drugs.

- Go online specifically to try to figure out what condition they or someone else might have.

- Consult online reviews about drugs and other treatments.

- Track their weight, diet, or exercise routine.

- Read online about someone else’s personal health experience.

- Go online to find others with similar health concerns.

An aging population and a rise in the percentage of people living with chronic conditions means that the United States will need to increasingly rely on family caregivers to provide front-line health care. This study presents evidence about how caregivers currently gather, share, and create health information and support.

Caring for both children and adults with significant health challenges

To measure the population of U.S. adults who provide care to loved ones with significant health issues, we asked a series of questions beginning with:

In the past 12 months, have you provided unpaid care to an adult relative or friend 18 years or older to help them take care of themselves? Unpaid care may include help with personal needs or household chores. It might be managing a person’s finances, arranging for outside services, or visiting regularly to see how they are doing. This person need not live with you.

Some 36% of U.S. adults say they provided such unpaid care to an adult in the past year, up from 27% in 2010.

Those respondents were then asked:

Do you provide this type of care to just one adult, or do you care for more than one adult?

Two-thirds (66%) of that group say they care for one adult, which represents one-quarter of the U.S. population ages 18 and older. One-third (34%) of people who are helping an adult relative or friend say they care for more than one adult.

Half (47%) of those who care for adults say at least one is their parent or parent-in-law.

Separately, we asked:

In the past 12 months, have you provided unpaid care to any child under the age of 18 because of a medical, behavioral, or other condition or disability? This could include care for ongoing medical conditions or serious short-term conditions, emotional or behavioral problems, or developmental problems, including mental retardation.

Eight percent of U.S. adults say the provided unpaid care to a child living with health challenges or disabilities, up from 5% in 2010.

In sum, 39% of U.S. adults are caregivers, up from 30% in 2010.[5. numoffset="5" “Family Caregivers Online,” by Susannah Fox and Joanna Brenner. (Pew Research Center: July 12, 2012). Available at:

https://legacy.pewresearch.org/internet/Reports/2012/Caregivers-online.aspx] As the U.S. population ages and medical advances save and extend more lives, caregiving is likely to become a more common role than it has ever been before.

Who are caregivers?

Caregiving touches every segment of the population. Men and women are equally likely to be caregivers. People of all age groups provide care for loved ones, with a slightly higher percentage of those ages 30-64 saying they do so. Caregivers are more likely than other adults to be married and to be employed full time.

They are also more likely than non-caregivers to have gone through a recent health crisis or to have experienced a significant change in their physical health (including positive changes, such as quitting smoking). (See Appendix for detailed tables.)

This finding dovetails with clinical studies showing that the stress associated with caregiving has an independent, negative effect on people’s health.[6. See, for example: “Caregiver Health” (Family Caregiver Alliance). Available at:

http://www.caregiver.org/caregiver/jsp/content_node.jsp?nodeid=1822]

Caregivers are wide-ranging online health information consumers

Fully 86% of caregivers have internet access, compared with 78% of non-caregivers. And 84% of caregivers with internet access say they went online within the past year to research health topics such as medical procedures, health insurance, and drug safety. By comparison, 64% of non-caregivers with internet access say they did online health research in the past 12 months.

For brevity’s sake, we will refer to those who research health topics as “online health seekers.” When calculated as a percentage of all U.S. adults, not just internet users, 72% of caregivers are online health seekers, compared with 50% of non-caregivers.

When controlling for age, income, education, ethnicity, and good overall health, being a caregiver increases the probability that someone will go online to look for health information. Living in a higher income household and reporting a higher level of education also increases someone’s likelihood to do health research online. Being age 40 or older decreases the probability that someone will do this type of research online.

We tested four topics and found that these patterns held for each one, that is, being a caregiver has an independent effect on someone’s likelihood to look online for information about:

- A specific disease or medical problem

- A certain medical treatment or procedure

- Drug safety or recalls

- A drug they saw advertised

In other words, caregivers’ appetite for certain kinds of online health information is related to their home health care role, independent of other demographic factors.

Most caregivers say the internet has been helpful to them

When asked if online resources are helpful:

- 59% of caregivers with internet access say that online resources have been helpful to their ability to provide care and support for the person in their care.

- 52% of caregivers with internet access say that online resources have been helpful to their ability to cope with the stress of being a caregiver.

Younger caregivers are more likely than older ones to report that the internet has been helpful to their ability to provide care and support: 70% of caregivers ages 18-29 say that, compared with 51% of those ages 50-64 years old. Two-thirds of male caregivers say the internet has been helpful in this way, compared with 55% of female caregivers.

Younger caregivers are also more likely than older ones to say the internet has been helpful in coping with related stress: 70% of caregivers ages 18-29 say that, compared with 43% of those ages 50-64 years old. There was no difference between men and women on this question, nor were there any other notable demographic differences.

Eight in ten online health inquiries start at a search engine

When asked to think about the last time they searched online for health information, 79% of caregivers who are online health seekers say they started at a search engine such as Google, Bing, or Yahoo. Fourteen percent started at a site that specializes in health information, such as WebMD. Just 1% say they started at a more general site like Wikipedia and another 1% started at a social networking site like Facebook. There are no significant differences between caregivers and non-caregivers when it comes to starting an online health inquiry at a search engine, specialized health website, or other site.

Overall, this matches what we found in our first health survey more than a decade ago. Then, as now, eight in ten online health seekers are likely to start at a general search engine when looking online for health or medical information.

Caregivers are likely to say their last health search was on behalf of someone else

Caring for others’ information needs is a common activity among all internet users. Half of all health searches are conducted on behalf of someone else. This long-standing pattern, measured in our first health survey in the year 2000, is particularly pronounced among caregivers: 63% say their last search was at least in part on behalf of someone else, compared with 47% of non-caregiver online health seekers.

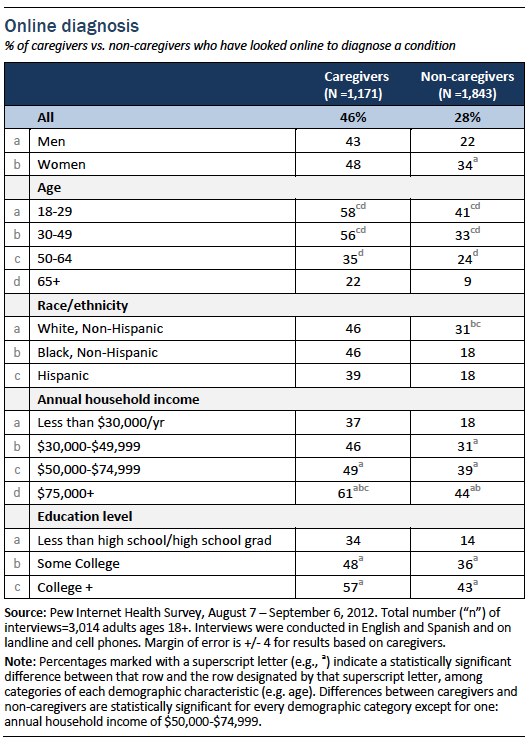

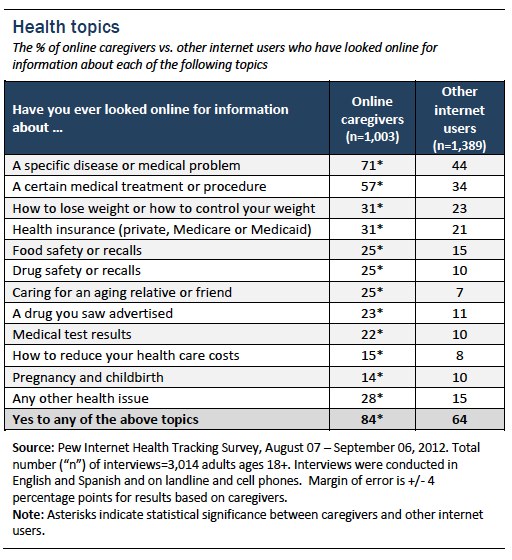

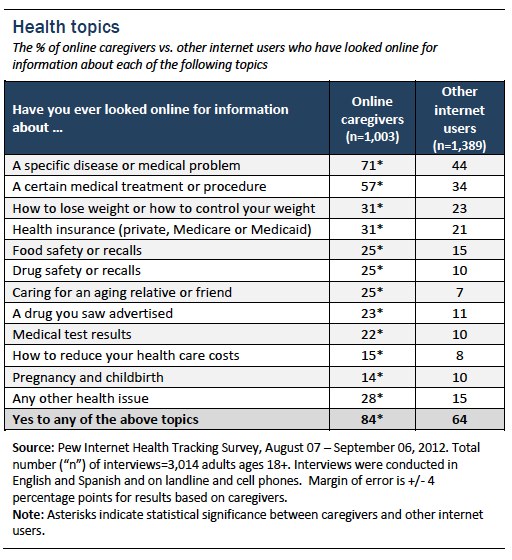

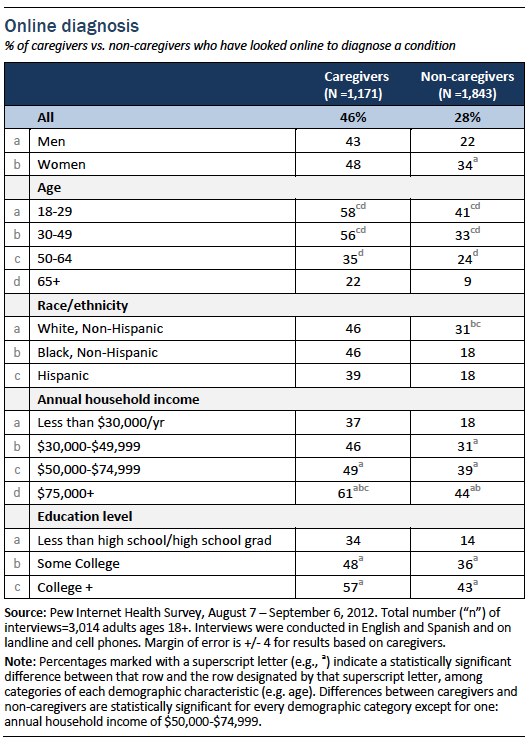

Nearly half of all caregivers have gone online to try to figure out a possible health diagnosis

Fully 46% of caregivers say they have gone online specifically to try to figure out what medical condition they or someone else might have. By comparison, 28% of all non-caregivers say they have done so. Note that these results are based on all U.S. adults, not just on internet users.

When controlling for age, income, education, ethnicity, and good overall health, being a caregiver greatly increases the probability someone will go online for a diagnosis. Living in a higher income household, being college educated, and being white each have an independent effect, increasing the likelihood of someone going online to try to figure out a medical condition. Being age 40 or older decreases the likelihood.

Bathing and dressing someone who needs help, driving to doctor appointments, sorting through paperwork, making sure this pill is taken with breakfast and that pill at bedtime—these hands-on, caregiving activities define the word “offline.”

Yet, these days, caregivers are health information specialists. They have the safety, comfort, and even the life of a loved one in their hands. They are asked to perform a dizzying array of medical and personal tasks outside clinical settings and the stakes are very high.[4. numoffset="4" “Home Alone: Family Caregivers Providing Complex Chronic Care,” by Susan C. Reinhard, Carol Levine, and Sarah Samis. (AARP Public Public Policy Institute and the United Hospital Fund: October 2012). Available at:

http://www.aarp.org/home-family/caregiving/info-10-2012/home-alone-family-caregivers-providing-complex-chronic-care.html] Caregivers display what we at the Pew Research Center have identified as a core social impact of the internet: the ability to quickly gather information on a complex topic to make decisions.

This national survey by the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project, supported by the California HealthCare Foundation, finds that caregivers are highly likely to gather advice from clinicians, family, friends, and peers; to track their own and their loved ones’ health data; and to use the internet to research health conditions and treatments.

We find that being a caregiver is a special factor highly correlated with certain kinds of online information seeking. When controlling for age, income, education, ethnicity, and good overall health, caregivers are more likely than other internet users to:

- Gather health information online, particularly about medical problems, treatments, and drugs.

- Go online specifically to try to figure out what condition they or someone else might have.

- Consult online reviews about drugs and other treatments.

- Track their weight, diet, or exercise routine.

- Read online about someone else’s personal health experience.

- Go online to find others with similar health concerns.

An aging population and a rise in the percentage of people living with chronic conditions means that the United States will need to increasingly rely on family caregivers to provide front-line health care. This study presents evidence about how caregivers currently gather, share, and create health information and support.

Caring for both children and adults with significant health challenges

To measure the population of U.S. adults who provide care to loved ones with significant health issues, we asked a series of questions beginning with:

In the past 12 months, have you provided unpaid care to an adult relative or friend 18 years or older to help them take care of themselves? Unpaid care may include help with personal needs or household chores. It might be managing a person’s finances, arranging for outside services, or visiting regularly to see how they are doing. This person need not live with you.

Some 36% of U.S. adults say they provided such unpaid care to an adult in the past year, up from 27% in 2010.

Those respondents were then asked:

Do you provide this type of care to just one adult, or do you care for more than one adult?

Two-thirds (66%) of that group say they care for one adult, which represents one-quarter of the U.S. population ages 18 and older. One-third (34%) of people who are helping an adult relative or friend say they care for more than one adult.

Half (47%) of those who care for adults say at least one is their parent or parent-in-law.

Separately, we asked:

In the past 12 months, have you provided unpaid care to any child under the age of 18 because of a medical, behavioral, or other condition or disability? This could include care for ongoing medical conditions or serious short-term conditions, emotional or behavioral problems, or developmental problems, including mental retardation.

Eight percent of U.S. adults say the provided unpaid care to a child living with health challenges or disabilities, up from 5% in 2010.

In sum, 39% of U.S. adults are caregivers, up from 30% in 2010.[5. numoffset="5" “Family Caregivers Online,” by Susannah Fox and Joanna Brenner. (Pew Research Center: July 12, 2012). Available at:

https://legacy.pewresearch.org/internet/Reports/2012/Caregivers-online.aspx] As the U.S. population ages and medical advances save and extend more lives, caregiving is likely to become a more common role than it has ever been before.

Who are caregivers?

Caregiving touches every segment of the population. Men and women are equally likely to be caregivers. People of all age groups provide care for loved ones, with a slightly higher percentage of those ages 30-64 saying they do so. Caregivers are more likely than other adults to be married and to be employed full time.

They are also more likely than non-caregivers to have gone through a recent health crisis or to have experienced a significant change in their physical health (including positive changes, such as quitting smoking). (See Appendix for detailed tables.)

This finding dovetails with clinical studies showing that the stress associated with caregiving has an independent, negative effect on people’s health.[6. See, for example: “Caregiver Health” (Family Caregiver Alliance). Available at:

http://www.caregiver.org/caregiver/jsp/content_node.jsp?nodeid=1822]

Caregivers are wide-ranging online health information consumers

Fully 86% of caregivers have internet access, compared with 78% of non-caregivers. And 84% of caregivers with internet access say they went online within the past year to research health topics such as medical procedures, health insurance, and drug safety. By comparison, 64% of non-caregivers with internet access say they did online health research in the past 12 months.

For brevity’s sake, we will refer to those who research health topics as “online health seekers.” When calculated as a percentage of all U.S. adults, not just internet users, 72% of caregivers are online health seekers, compared with 50% of non-caregivers.

When controlling for age, income, education, ethnicity, and good overall health, being a caregiver increases the probability that someone will go online to look for health information. Living in a higher income household and reporting a higher level of education also increases someone’s likelihood to do health research online. Being age 40 or older decreases the probability that someone will do this type of research online.

We tested four topics and found that these patterns held for each one, that is, being a caregiver has an independent effect on someone’s likelihood to look online for information about:

- A specific disease or medical problem

- A certain medical treatment or procedure

- Drug safety or recalls

- A drug they saw advertised

In other words, caregivers’ appetite for certain kinds of online health information is related to their home health care role, independent of other demographic factors.

Most caregivers say the internet has been helpful to them

When asked if online resources are helpful:

- 59% of caregivers with internet access say that online resources have been helpful to their ability to provide care and support for the person in their care.

- 52% of caregivers with internet access say that online resources have been helpful to their ability to cope with the stress of being a caregiver.

Younger caregivers are more likely than older ones to report that the internet has been helpful to their ability to provide care and support: 70% of caregivers ages 18-29 say that, compared with 51% of those ages 50-64 years old. Two-thirds of male caregivers say the internet has been helpful in this way, compared with 55% of female caregivers.

Younger caregivers are also more likely than older ones to say the internet has been helpful in coping with related stress: 70% of caregivers ages 18-29 say that, compared with 43% of those ages 50-64 years old. There was no difference between men and women on this question, nor were there any other notable demographic differences.

Eight in ten online health inquiries start at a search engine

When asked to think about the last time they searched online for health information, 79% of caregivers who are online health seekers say they started at a search engine such as Google, Bing, or Yahoo. Fourteen percent started at a site that specializes in health information, such as WebMD. Just 1% say they started at a more general site like Wikipedia and another 1% started at a social networking site like Facebook. There are no significant differences between caregivers and non-caregivers when it comes to starting an online health inquiry at a search engine, specialized health website, or other site.

Overall, this matches what we found in our first health survey more than a decade ago. Then, as now, eight in ten online health seekers are likely to start at a general search engine when looking online for health or medical information.

Caregivers are likely to say their last health search was on behalf of someone else

Caring for others’ information needs is a common activity among all internet users. Half of all health searches are conducted on behalf of someone else. This long-standing pattern, measured in our first health survey in the year 2000, is particularly pronounced among caregivers: 63% say their last search was at least in part on behalf of someone else, compared with 47% of non-caregiver online health seekers.

Nearly half of all caregivers have gone online to try to figure out a possible health diagnosis

Fully 46% of caregivers say they have gone online specifically to try to figure out what medical condition they or someone else might have. By comparison, 28% of all non-caregivers say they have done so. Note that these results are based on all U.S. adults, not just on internet users.

When controlling for age, income, education, ethnicity, and good overall health, being a caregiver greatly increases the probability someone will go online for a diagnosis. Living in a higher income household, being college educated, and being white each have an independent effect, increasing the likelihood of someone going online to try to figure out a medical condition. Being age 40 or older decreases the likelihood.

Medication management is a significant challenge for many caregivers

A 2012 study by the AARP Public Policy Institute and the United Hospital Fund reported that nearly half of caregivers perform complex medical and nursing care at home, such as managing multiple medications, preparing meals to adhere to a special diet, and attending to wounds.[7. numoffset="7" AARP Public Policy Institute and United Hospital Fund, 2012.] Caregivers reported that these tasks are difficult and many would like to receive training, particularly for medication management since the result of making a mistake is so dire.

In order to build on those findings, we asked caregivers:

Do you manage medications for the people you help care for, such as checking to be sure they are taken properly or refilling prescriptions, or is this not something you do for them?

Thirty-nine percent of caregivers say yes, they manage medications. Women are more likely than men to say they manage a loved one’s medications: 47% of female caregivers do so, compared with 38% of male caregivers. Caregivers age 30 and older are more likely than those between the ages of 18 to 29 to say they manage medications. There are no significant differences among education, income, or ethnic groups.

Of those who manage medications, 18% say they use online or mobile tools, such as websites or apps, to do so, which translates to 7% of all caregivers. College graduates are the most likely group to use technology to track medications. Otherwise, there are no significant differences among caregivers along age, income, or ethnic lines.

Nine in ten caregivers own a cell phone and one-third have used it to gather health information

Eighty-seven percent of caregivers in the United States own a cell phone and, of those, 37% say they have used their phone to look for health or medical information online. This is significantly higher than the rate of mobile health search among non-caregivers at the time of the survey: 84% of non-caregivers own a cell phone and 27% have used their phone to look online for health information.

Paywalls do not deter most caregivers; few actually pay