Throughout focus group discussions, teachers noted that their experiences with middle and high school students cannot be isolated from broader trends shaping this generation, and that much of what they see in their students’ academic habits, characteristics, and attitudes are reflections of much broader impacts of growing up in a digital age. To probe these issues more fully, the survey posed several questions asking teachers to evaluate today’s students compared to prior generations, in terms of basic skills and habits such as attention and distraction, cognition, multi-tasking, media literacy, and overall literacy. Overall, in the eyes of their teachers, today’s middle and high school students compare both favorably and unfavorably with prior generations. Yet there are widely varying opinions among teachers about how “unique” this generation is, and how they compare with predecessors on specific dimensions

Teachers are divided on whether “digital natives” are fundamentally different than prior generations of students

On the whole, teachers are divided on the question of whether today’s students are fundamentally different from previous generations. For instance, 47% of teachers surveyed agree with the statement that “today’s students are really no different than previous generations, they just have different tools through which to express themselves,” while 52% disagree with that statement. Surprisingly, teachers’ views of this statement are consistent across virtually all subgroups, including teacher age and experience, grade level taught, community type, student socioeconomic status, and subject taught.

When asked in another item, however, whether they agree or disagree that “today’s students have fundamentally different cognitive skills because of the digital technologies they have grown up with” 88% of the teachers surveyed agree, including 40% who “strongly agree.” Teachers of the lowest income students are most likely to “strongly agree” with this statement (46%) but the difference across student socioeconomic status only ranges from 37% (mostly lower middle income) to 46%, and there are no other notable differences across subgroups of the sample.

Focus group participants were likewise split on the question of how unique today’s students are. Some feel that growing up in the digital world has significantly impacted the way today’s students think and process information, yet an equal proportion of teachers expressed the opposing view, arguing that what they see in their students today is no different than what they have always encountered teaching young people. They suggest that while key habits and characteristics may take a different form, or be expressed differently, the underlying challenges they face teaching middle and high school students are the same today as they were prior to the digital explosion.

I’ve been teaching for 25 years and I don’t think teens have changed that much. As I mentioned previously, my students can read deeply and think critically about challenging texts as well as my generation did. They are capable of doing thorough research and critically evaluate information, the can form persuasive appeals, they’re effective writers. I think what’s different is the amount of information that they have to critically evaluate, and the amount of spin that they have to deal with in commercial and political communication. – National Writing Project teacher

I would say that our students are asked to digest much more information than I ever was. That’s got to be tough. It’s tough to know which information to read deeply, which site will offer credible sources. Schools should address this more. If anything, schools are slower to respond to the needs of students now than they were in the past. Maybe, this is why it is perceived that today’s students are lagging behind those of the past. If as educators, we do not accept the responsibility to teach our students the skills to navigate messages, information, multiple identities, and other demands that these technologies place on our youth, future generations will certainly fail to meet the current demands. – National Writing Project teacher

Just today in a staff meeting we were talking about students not studying for tests. Older (more experienced) teachers in the room started to lament about how students are not studying for tests the way they used to when they were in school. The teachers recalled times in their life when they would sit at the kitchen table or at the desk in their room actually going over their reviews and their notes to study and prepare for a specific tests. As I listened to them talk, I thought back to my own studying experiences. I can’t say that I can remember spending tons of time studying for a specific test. If a teacher gave us a review sheet I would always complete the review sheet, but did I myself ever study the material before the test? The answer is no, I did not. So is this current class of students really that much different from a class ten, fifteen, twenty years ago? I’m not convinced that there really is a difference…I am not convinced that this current group of students is any more or less skilled at any of the items than that of previous generations. – National Writing Project teacher

Teachers say today’s students are more media savvy, but also less literate and more distracted than previous generations

Asked to evaluate this generation on more specific skills and characteristics, a vast majority of survey participants agree with the notion that “today’s students are more media savvy than previous generations” (86%). Yet, almost as many teachers disagree with the statement that “today’s students are more literate than previous generations” (80%).

Older, more experienced teachers are slightly more likely than their younger counterparts to “strongly agree” with the idea that today’s students are more media savvy than prior generations. Among teachers ages 55 and older, 61% “strongly agree” with this idea, compared with 50% of younger teachers. Similarly, while 56% of those who have been teaching for 16 years or longer “strongly agree” that today’s students are more media savvy than prior generations, the same is true of 50% of those who have not been teaching as long.

On the question of whether today’s students are more literate than previous generations, teachers teaching in large metro areas or cities are particularly likely to “strongly disagree” with this statement; more than one in five (23%) “strongly disagree” that today’s students are more literate compared with 16% of teachers in rural areas. Teachers of the lowest income students, those living in poverty, also strongly dispute this statement. One-third of this group (33%) “strongly disagree” that today’s students are more literate than students of the past, while another 48% “somewhat disagree.”

The question of overall literacy among students is one that arose often in focus group discussions. Not only did some focus group participants feel that today’s students are no more literate than prior generations, they also feel their students may be losing ground in this area. Typical of these concerns is the following excerpt from a focus group with teachers at a College Board school, in which several teachers suggested that diminishing writing skills may be due in part to a diminishing desire to read in general, and a diminishing ability to read difficult texts. While focus group participants disagreed as to whether the underlying issue is a lack of skill or a lack of interest or focus, there was general agreement in this group that today’s students are reading less:

R: They [students] don’t read. There are readers and then there’s everybody else, and the readers are like few and far between. They don’t read even though we push them to read.

R: The ability to focus on one task which is a lot of what we’re talking about here, to read a book from cover to cover and be able to do that and that alone is becoming enormously difficult. We’re reading Brave New World in our ELA class now for tenth grade ELA which is a staple book that every high school student has read for many, many years now. The book itself is about 170 or 175 pages. It’s not a long book. It’s certainly a book that’s rich in ideas and rich in language but it’s not a long book. I would say in terms of the section I teach, which is the [removed] section, I want to say of that 170 pages the average student has read between 40 and 45 so far and the book is supposed to have been completed last week. Now we read Romeo and Juliet before that. Again, the majority of the class did not complete reading the play…Now I certainly can’t speak for any other teacher here in terms of the percentage or the amount of text that they’re completing or not completing, but it does concern me. Again, I’m trying to find out why – why is this happening? And the answers I’m getting are pretty stock. I find that it’s boring, it’s not interesting.

M: But do you think they’re not capable of doing it or do you think they don’t see value?

R: No, no, I think the latter. I certainly think except for a very, very small percentage who might have more severe learning disabilities, a very, very small percentage, every student at this school is more than capable of reading.

M: So it’s not that the technology actually is limiting their ability to read long texts deeply. It’s that it’s diminishing the value of doing it?

R: I believe that is a component. I’d like to see more research done with that. I’d also like to see surveys conducted and get more quantitative data on that.

R: I respectfully disagree…but I totally agree with [other teacher] that the internet has done a number and has weakened students’ ability to read for depth, to read for long periods of time and the idea of reading for enjoyment. I didn’t go to school that long ago but I remember that everybody liked to read something, whether it was Sports Illustrated or it was what you call it, science fiction stuff. Everybody liked to read something and we see a lot of students today who aren’t interested in reading anything, and I think that technology…that they become much more functional readers. It does connect to what [other teacher] was saying in that they’re reading stuff to get information and it goes to the speed piece, too. ‘I’m reading it to get the information to do what I need to do and that’s it.’ Why would I sit down and read a 180-page book? What am I going to get there? What’s in it for me? I’ve got to go. I’ve got things to do.

R: I don’t think a lot of them are reading at all. I think that any kind of reading would be wonderful. Reading a comic book would be wonderful. Reading a graphic novel would be wonderful. Reading an online article would be wonderful. They’re not reading anything. They’re looking at pictures, they’re playing video games, and they’re on Facebook reading posts. I’m not talking about reading posts on Facebook. Reading something that takes some kind of stamina, it doesn’t matter even what the content is.

R: I think many of the kids are reading but they are reading shorter things, one to four pages. Newspapers, I know a lot of our kids read newspapers which fits with [the focus of] the school. A lot of them read magazines. I’ve seen that some of the younger grades would get the scholastic magazines. They’ll read those but it’s always the same problem, you’re reading anywhere from one to six pages and they just – it’s a habit like anything else. You get into this mindset where you’ve got a short, maybe just one to six pages and pretty much done and I think they’ve got a great deal of difficulty segueing over to books which require more stamina and picking it and reading 10, 15, 20, 30, 40 pages, or even reading from beginning to end.

Yet, in the same discussion, teachers spoke about the promise of digital tools to address what others see as an inability or unwillingness of their students to take on long and challenging texts. As one teacher explained:

The other thing that — I want to end on a positive note — is that we did read Of Mice and Men in the class and we did get I would say like 98% of the people were reading it, and it could be framed as boring but we didn’t. We framed it in an interesting way and they liked it. Some kids did download it on their phones and some kids did have Nooks and Kindles and they brought them in and that was their way of doing it and they found ways to highlight and everything, so that did help some of the kids who couldn’t get access to a printed copy. So I think that was a positive.

R: But that said…the not reading book-length material goes back to [them being] used to short, not only well-edited, sometimes poorly written, but certainly short and not richly written material that they read on the internet. But that’s where their primary source of information now is either going to be internet, magazines or newspapers. They’re not doing books so I think one of the things I’d like to see in the schools is things like Nooks getting cheap enough [so] we can buy classrooms some Nooks or have enough that we can check them out or have a room where they can check out a Nook or read a book and have a place to read it. They might do that if the technology is there that makes the book accessible. They have a place where they cannot go to lunch where it’s crazy, [but] come up and have a quiet room. But that would require probably buying anywhere from 50 to 100 units. I mean it would be a great idea.

In an online focus group with NWP Summer Institute teachers, participants were asked the value of students being able to read challenging (often long) texts critically in today’s digital world. Across the board, these teachers continue to see tremendous value in this skill, and view it as essential for students to function in an information-based world. However, some teachers in this group also questioned whether this is a fading skill among “digital natives.”

Reading critically is about thinking and learning. Yes, I do believe that being challenged with reading is critical for the purpose of learning and thinking. No matter what students do in the future this skill is essential. Everyone will have to read through tough texts and explore various audiences. I want my students to be able to tackle texts in a smart manner. Critical reading applies to reading our world, understanding lease terms for a car or apartment, or analyzing situations at a job. I don’t want my students to be passive or miss opportunities for being part of a discussion because a text is something they cannot approach. I think students need experiences being challenged, so that they will take the challenge later on too and challenge their continual thinking and learning and engaging in various conversations. – National Writing Project teacher

Whether they are college bound or not, we need students to be provided the opportunities to develop the skills to read and critically think about anything they read – be it a lengthy scholarly article, a blog post, or be it the constitution of the United States. By educating our youth to read and critically examine what they read we are helping to create an educated and informed society. I want to know that my students are able to go out into the “world” and make informed decisions about such things as the rules that govern our society, the politicians that are elected who shape the future of our nation, to the fine print on a credit card policy that can affect their future financial standing. – National Writing Project teacher

The value of teaching students to engage with long and challenging texts is that it’s a worthwhile journey. There’s something about staying with a problem until you get it (or work through it or wrestle with it or whatever) that is satisfying in and of itself. I’d like to think I’m teaching them to value the act of learning for its own sake. I know a lot of us choose an inquiry approach to teaching writing, and for me a student’s inquiry starts to get interesting once you get beyond the givens and the knowns. That’s the kind of learning I want them to value. I hear a lot of education people talk about the future and that we’re preparing students to solve problems that we don’t know the answer to. How else do you get there unless you critically examine challenging ideas? I suppose the question is, can’t you do that without reading long and challenging texts, but I prefer to do things like blast through texts like The Tempest in one or two classes and then asking the students, “Now what just happened?” I could spoon-feed it to them over the course of a month, but the ideas they generate on their own when they have to deal with that long and challenging text is worth it. – National Writing Project teacher

The main purpose and value of critically reading long and challenging texts is that there are a whole lot of ideas and concepts that simply cannot be reduced to short and simple texts without seriously compromising their meaning or value. It absolutely remains a critical skill for students today, if for no other reason than the problems that the world faces are increasingly complex and challenging. This truth informs writing, be it fiction or non-fiction. Moreover, with the breakdown of traditional forms of publishing and, in some cases, editorial review makes critical reading more important than ever. All readers must now be readers, researchers, and editors perforce. I often say to students that if you do not learn how to read challenging texts critically, it is very likely that someone, somewhere will simply take advantage of them or dupe them. Worse still, they might not even now it. – National Writing Project teacher

When it comes to students “reading deeply” I strongly believe students struggle with the concept of thinking critically. Students have information thrown at them in fast, small bits. To get a student to sit down with an authentic article and have a conversation with it, is very challenging. Students don’t ask questions of the reading and wonder if it is valid. They just take it most times at face value. Most responses are simply “yes, I like it”, or “No, I think the article was dumb”. – National Writing Project teacher

Distraction and time management are hot button issues for teachers

The topic which generated perhaps the most intense discussion was that of “digital distractions” and their impact on today’s teens. Overwhelming majorities of survey participants agreed with the assertion that “today’s digital technologies are creating an easily distracted generation with short attention spans” (87%) and that “today’s students are too ‘plugged in’ and need more time away from their digital technologies” (86%).

The former statement suggesting that digital technologies create an easily distracted generation elicited consistent responses across all subgroups of teachers, with no notable differences across teachers’ age, grade level taught, or years in the classroom. The latter statement suggesting students are “too plugged in” resonated slightly more with older teachers in the sample and among high school teachers. Among teachers ages 55 and older, 41% “strongly agree” with this statement, compared with 37% of teachers ages 35-54 and 32% of teachers ages 22-34. Interestingly, years teaching does not correlate with responses to this item. And while 32% of 6th-8th grade teachers “strongly agree” today’s students are “too plugged in,” the same is true of 39% of 9th-10th grade teachers and 37% of 11th-12th grade teachers. While these differences are notable, they are fairly small.

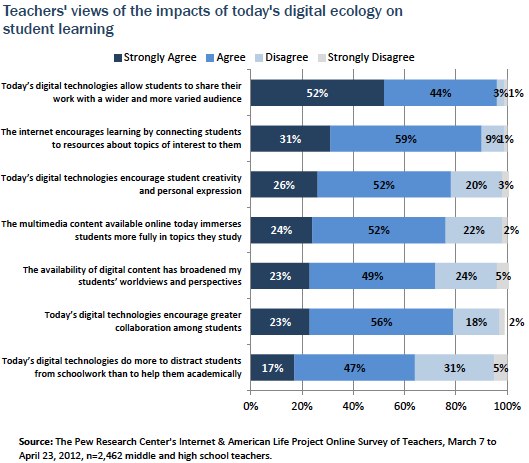

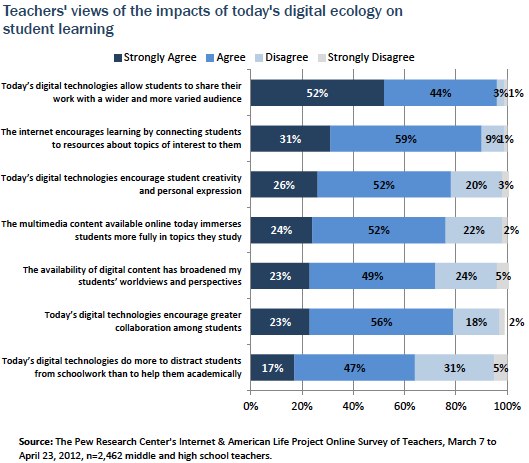

Moreover, in contrast to the many positive aspects of learning in a digital age teachers point to, nearly two-thirds of the AP and NWP teachers surveyed see digital technologies as “doing more to distract students than to help them academically.” Fully 64% of survey respondents agree to some extent with this notion, including 17% who “strongly agree,” indicating that while these teachers generally embrace the power of the internet and other digital tools to encourage and foster greater learning, many also worry that today’s digital environment results in more distracted students. High school teachers express more concern than middle school teachers when it comes to digital distractions. One in five 11th-12th grade teachers (19%) “strongly agree” that today’s digital tools do more to distract their students than to help them in the classroom, as do 17% of 9th-10th grade teachers. Among middle school teachers, 12% “strongly agree” this is the case.

Asked about their students’ ability to multi-task in an age of constant information and distraction, teachers are more divided, with 46% agreeing that today’s students are “very skilled” in this area and 53% disagreeing. Surprisingly, teachers of middle school students are more likely to say this is true than are those teaching high school students. Among 6th-8th grade teachers, 54% agree to some degree with this statement, including 13% who “strongly agree.” Slightly fewer 11th-12th grade teachers (49%) agree at least somewhat that today’s students are “very skilled” multi-taskers. Even fewer 9th-10th grade teachers (45%) agree at least somewhat that today’s students are skilled multi-taskers.

Teachers with more years in the classroom are actually more likely to agree with this statement than are those who have been in the classroom 15 years or fewer. Half of more experienced teachers (50%) agree at least somewhat that their students are skilled multi-taskers; that figure drops to 45% among newer teachers. This is a small difference, but may indicate that more experienced teachers see today’s generation comparing favorably to prior generations on this skill, particularly given the amount of information and constant communication today’s students are exposed to.

In focus groups, participants expressed concern about the following elements of “digital culture” and their impact on students’ ability to focus and their time management:

- Students’ “overexposure” to technology—and the multi-tasking that often accompanies the use of these technologies—contributes to lack of focus and diminished ability to retain knowledge

- Students do not set aside enough time for crucial tasks, and often use the various digital tools at their disposal to “waste time” and procrastinate

- Some students’ “addiction” to online gaming and video games consumes their time and attention

- Students are so often “plugged in” that they are missing out on the world around them

- “Overexposure” and “overuse” of digital technologies is not actually making students more technologically literate or more efficient

In online focus groups with AP teachers, participants were specifically asked if they were “concerned that students are overexposed to technology.” Nearly all participants answered affirmatively that they see their students as “overexposed,” and expressed concern about the impact digital technologies might be having on their students both in terms of their performance in school as well as their wellbeing outside of school. Several participants worried that social media, cell phones, and other tech gadgets are being “abused” by students, and that students are “overstimulated” by doing too many things at once.

Moreover, many teachers worry that these tools are adversely impacting students’ time management skills, fostering a (sometimes false) sense that all tasks can be completed quickly and at the last minute because so much information is so easily available. Several teachers suggested that it is critical for students to learn time management skills in their middle and high school years, or else it may harm their future success. They see time management skills as becoming increasingly important in a fast-paced digital world; at the same time, they see the skill potentially declining in their students.

Yet, almost as many teachers argued that today’s students are not more easily distracted than prior generations, citing examples of students engaging with assignments over long periods of time. The difference, some teachers suggest, is that today’s students are easily bored by information that is presented in “traditional” ways and that teachers need to adjust their methods to engage students using the digital tools and formats that hold their attention. Some argue that today’s students are able to handle more information at one time because of the digital environment in which they have grown up, and that rather than being described as “easily distracted,” they should be viewed as being highly skilled at dividing their attention across several things at one time.

They just surf the Internet and mess around with Facebook and every other thing, they’ll do it until 11:00 or 12:00 or 1:00, and then they’ll think they can do their project in one hour. I think that’s the biggest problem; while the Internet can be a strength, it’s also a huge problem, even in the classroom, unless you got it set up to monitor every screen… they’re going to be looking at pictures of their latest film star, music star or anything else. They will do anything to not do work; and it’s a real problem at home. — Teacher at College Board School

Tabbed browsing has made things so much worse…It makes things so much worse and so much harder because you don’t even know when you’re in your g-mail. People are messaging you and let’s say you’re trying to do whatever and then it’s like, ding! You’re like, “Oh, what is it?” Then you’ve got to chat. Then you’re like, okay, I’ve taken care of that, I’m going back to what I need to do and then it’s like, ding!…I can’t even imagine for kids how many tabs they have open. — Teacher at College Board School

[The internet] does make research so much easier and it’s easy to get things done if you put in the time and you focus. So even though students kind of wait until the last minute at 11:00, they probably can get a lot of assignments done in a short period of time if they focused. But because of Facebook, because of tab browsing, the reality is they’re not focusing. They’re so used to multi-tasking in every other part of their life that when it does come down to that one assignment the only way they’re going to get it done and do it well is to focus, they can’t. They can’t turn other things off because they’re so used to having everything on all the time. — Teacher at College Board School

Since they don’t have to schedule time to do all these things and since they feel that they can do in five hours what would’ve taken me when I was in high school perhaps a good month…they can literally procrastinate. I think our curriculum – at least as I see it now and even with the common core standards – in no way addresses these time management skills, which are so critical. How then do we teach time management with this technology that will forever be used, it’s forever going to be improved upon, it is only going to become faster and it’s only going to allow them to multitask at a quicker pace, expect – and the expectations are so much greater then? If we can’t do that, then we’re not preparing them for college work, and we’re certainly not preparing them for the workforce. — Teacher at College Board School

Interestingly, for the last few years I have been having my ninth grade students read Nicholas Carr’s article “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” from The Atlantic, which addresses this very issue. I have them read the article and write a response. By a slim majority, they themselves believe that digital technologies might in fact be undermining their ability to focus and shorten their attention spans. – National Writing Project teacher

I’m not sure if it’s apathy, but I do believe that the Internet, as it is used now, allows students to delay time management. If I had to point to one issue which affects the entire human race that certainly affects adolescence, it’s time management skills, and this is the age from, say, thirteen to eighteen or nineteen, when these skills become more and more of a requirement. It’s no longer optional that you understand how to manage your time; it’s a requirement because it is what’s expected of them as they move into adulthood and as they move into their professional and personal lives. The Internet has completely changed, irrevocably changed how time management skills are going to be taught, how they’re going to be used… – National Writing Project teacher

There is an essay for my tenth grade English Language Arts class that is due next Friday…The essay has been up there for a good six weeks now, yet I’m hearing feedback from the students that I’m working with that “Well, the information is there for me; therefore, I can just do this a couple of days beforehand. I’ll have plenty of time to get it done.” And I hear this with many students in many classes – since it’s so easy to access the website, since they don’t have to put away time, schedule time to go to a library, since they don’t have to schedule time to use a typewriter…I don’t want to make a blanket statement and say that’s true for every student, because it’s not. We do have students here who do an excellent job of managing their time and using the technology effectively and efficiently, but I would say that is overall the biggest problem I see with students these days. – National Writing Project teacher

I have watched my own children very engaged in authentic conversations for hours on social media. So I guess that I would have to say that it would just depend on the students. I know many of my students would not be distracted, because they are very task-oriented; however, I have several students who would be totally distracted by everything that is going on, Facebook for example. These are the same students that struggle to stay on-task everyday in most environments. Students need to learn to focus, because the world we live in is full of distractions. – National Writing Project teacher

When students are using technology, the hour zooms by and they are completely engaged. I find this true, for example, when they create digital stories. I also agree with [other teacher’s] point about online distractions. When doing research online for a report, it is so tempting for students to open another screen and check out Derrick Rose’s new lightweight basketball shoes. In fact, I think I might check those out right now…my daughter has been asking for a pair….and then I’ll check my school e-mail…and then my g-mail account…be back soon! – National Writing Project teacher (during online focus group)

I had my students read “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” at the start of the school year for the past couple of years. Across the board, they say that Carr is selling their generation short. They feel that they can do both deep reading and the shorter, connective bursts of reading online – the two aren’t mutually exclusive. To use Carr’s analogy, they like to jet ski and scuba dive. Like Joel’s students, mine can be absorbed in digital composition or the free reading of actual books for up to (and over) an hour. Actually the length of their attention spans in my classroom often correlates to those times when the conditions for sustained learning aren’t present (e.g. the day before Christmas vacation, the days when teacher doesn’t have his act together, emergency preparedness drill days). So I disagree with this and see it as an attention-span awareness issue. – National Writing Project teacher

I don’t know if it’s a question of attention spans. I believe digital technologies have fostered a sense of instant gratification. If they wonder about something, they Google it. If they want to see a trailer of a movie that they just read about, they can to a website or app. I don’t think it undermines student abilities to focus, I think technologies can hasten the information students seek. It’s up to parents and teachers to teach students how to judge which information, which interests and inquiries, are worth seeking and when. Follow through and accountability must be explored. These are important discussions to have. Essential. – National Writing Project teacher

Considering my own students over the years, I don’t agree that digital technologies diminish students’ attention spans. I know students who will read for hours and spend extra time outside of school writing and working on projects because they are engaged and enthusiastic in learning more about topics that interest them. If anything, technology tools provide my students opportunities to participate in learning activities and extend their learning beyond the school day if they want. Students write entries and comment on each other’s Edmodo posts in the evenings and weekends without any requirement from me to do so. – National Writing Project teacher

Finally, some teachers in this study feel that the question of “digital distraction” may be a red herring, diverting attention away from other issues that need to be addressed in the classroom and society at large. Several suggest that the notion of student “distraction” should be reframed not as a problem with today’s students, but as a problem with teachers, parents, and the broader educational system. For these teachers, the “distracted” label is drawing attention away from a lack of technological skill or understanding among some parents, teachers, and administrators, which they see as the main issue to be addressed. Several labeled it an “excuse” adults use to avoid changing their own behavior and teaching methods. Others point out that the issue of “distraction,” valid or not, is a moot point; digital technologies will continue to emerge and shape the world in which teens and adults live, and educators must adapt to this environment.

I think this is not only an issue for students and digital natives, but all of us. Before smartphones and the internet, I was not nearly the multi-tasker that I am today. We have all become accustomed to checking email regularly throughout the day, and while we may be hesitant to admit it, most of us are also interacting with Facebook, Twitter, texts, and other social media throughout the day as well. There are so many things that now fight for our attention, but this is the world we live in and I believe our responsibility is to give our students opportunities and guidance in managing their time. Three years ago when my school first introduced laptops and a model that allows for quite a bit of student freedom, and consequently encourages creativity and critical thinking, our students floundered. Access to the internet was overwhelming – so much music to find and download, friends to chat with, status to update. Most struggled to keep up with their work. There were many faculty debates about how to lock things down and take power and control out of the hands of students, but in the end no school-wide mandates were ever enacted. Today these same students have become efficient multi-taskers. Do they still check their Facebook accounts? Yes, of course they do, but even some of the rowdiest, least academically-focused students have learned how to balance. – National Writing Project teacher

I think that point of view described in your question is a convenient excuse for adults who do not want to take the time to learn about burgeoning developments in technology. Kids have been bored by things long before I was born and will continue to be long after I’m gone. When you learn how to use a tool, when you learn how to mentor a tool, then you have learned how to guide an adolescent to get the most out of it. Learning and thinking is never boring. If a kid is bored by technology or has lost focus or attention then he isn’t learning and thinking. It is a people (pedagogy) problem and not a tool problem. – National Writing Project teacher

The problem with the argument is that, at the end of the day, it doesn’t really matter. Students are using digital technologies and tools outside of class (and often in classes without teachers’ permission). These are likely going to be job-related skills as well. Are students distracted and often floundering at multi-tasking. Sure. But I think this speaks to larger challenges with updating classroom pedagogy than with a problem with students. – National Writing Project teacher

I tend to be on the fence about this statement. Students today generally have a shorter attention span, but it is due to how information is delivered to students today. The technologies mentioned above are not to blame for students having a short attention span. – National Writing Project teacher

I wouldn’t say that any of these technologies are shortening their attention spans. Look at how long kids will play a video game — for hours and hours and hours. If anything, right or wrong, I think students have less tolerance for the boring stuff we try to shove down their throats. In some ways they are saying, “Teacher you are boring. I want you to entertain me.” Now, obviously, I’m not saying that teachers should turn into some comedian routine just for the sake of entertaining kids, but we must consider all of the other things out there in the world that do grab kids attention. Their attention span is still there, it is just more selective about what it will devote itself to. As teachers we must take this into consideration and plan things for kids that they will be willing to spend their time working on. A few months ago, I had a couple of students who worked on a project for our class using video game components. They spent HOURS and HOURS working on this project and actually had a very in depth understanding of what they created. – National Writing Project teacher

I know when I have kids editing video to make a movie they care about they are fixated to the point where time ceases to exist. The bell will ring and I will hear, “Is that our bell? Geez. This class is too short.” That sounds like focus to me. I also know that when my 10th graders read their independent novels in class they are pin drop quiet and immersed in their books. You can almost smell their brains working…I don’t think attention spans are shortened on a physiological level — I think that we must have real conversations and present thoughtful articles to our students about how our digital practices might be impacting or undermining our writing, reading, and thinking. We can’t make Words With Friends or Facebook or Google Docs or cell phones go away, but we can have conversations in a valued literacy community (our classrooms) about the positive and negative impact of these tools. The ability to move between different media, different sources of information to piece together your thoughts while being bombarded by fragments… I guess these abilities might look like a short attention span, but maybe these are habits that students have developed to adapt to their media environments. – National Writing Project teacher