Beyond simply shaping research habits and practices, this population of middle and high school teachers suggests that the very definition of what “research” is has changed considerably in the digital world, and that change is reflected in how their students approach the task. The growing use and popularity of search engines among all segments of the population as a critical tool for finding information is reflected in today’s middle and high school students, who have not known a world without these tools. As a result, their very conception of “research” may be fundamentally different from prior generations.

“Research = Googling”

According to the teachers in this study, perhaps the most fundamental impact of the internet and digital tools on how students conduct research is how today’s digital environment is changing the very definition of what “research” is and what it means to “do research.” Ultimately, some teachers say, for students today, “research = Googling.” Specifically asked how their students would define the term “research,” most teachers felt that students would define the process as independently gathering information by “looking it up” or “Googling.” And when asked how middle and high school students today “do research,” the first response in every focus group, teachers and students, was “Google.”

In focus group discussions, teachers framed prior generations’ research practices as a time-consuming process that involved formulating a clear research question and then seeking out relevant and accurate information from trusted sources (mainly libraries), often with the aid of an expert (such as a reference librarian). In contrast, many suggest that today’s students define and approach the process of “doing research” very differently. What was once a slow process that ideally included intellectual curiosity and discovery is becoming a faster-paced, short-term exercise aimed at locating just enough information to complete an assignment. Teachers noted that this trend is driven not only by the immediacy and ease of the online search process, but also the time constraints today’s students face in their lives more generally.

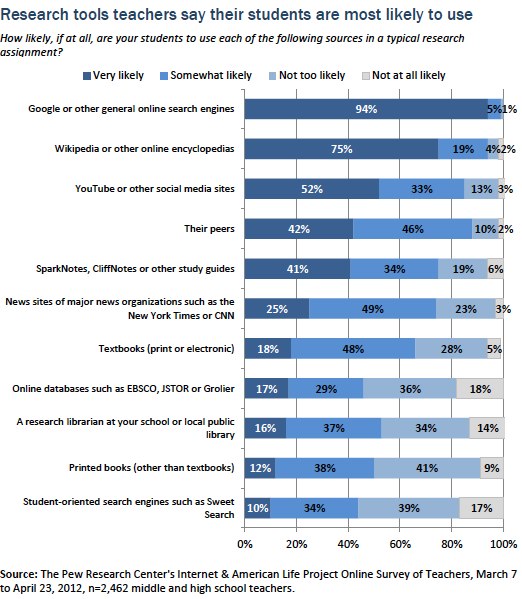

The survey reveals search engines top the list of resources students use

Teachers’ perceptions that their students use only a handful of resources and rely mainly on search engines for their research are echoed in survey results. Asked how likely their students were to use a variety of different information sources for a typical research assignment, 94% of the teachers participating in the survey said their students were “very likely” to use Google or other online search engines, placing it well ahead of the other sources asked about. Second to search engines was the use of Wikipedia or other online encyclopedias, which 75% of teachers said their students were “very likely” to use in a typical research assignment. And rounding out the top three was YouTube or other social media sites, which about half of teachers (52%) said their students were “very likely” to use.

Virtually all subgroups of this sample of AP and NWP teachers reported similar levels of student use of search engines. The only exception to this pattern was among teachers of the lowest income students (those living below the poverty line); this group was slightly less inclined (at 90%) to say their students are “very likely” to use search engines in a typical research assignment. This group was also among the least likely to report their students are “very likely” to use Wikipedia and other online encyclopedias (68% compared with 75% of the total sample). In contrast, 80% of teachers whose students are described as mostly upper and upper middle income say their students are “very likely” to use sites like Wikipedia.

The use of online encyclopedias as research tools also varied slightly by subject taught, with English teachers at the low end (69%) and science teachers at the high end (82%) of the range of those saying their students are “very likely” to use this source. English teachers are also the least likely to describe their students as “very likely” to use YouTube and other social media sites in a typical research assignment, with 44% reporting this level of use. The figure for the sample of teachers as a whole is slightly higher at 52%.

More “traditional” sources of information, such as textbooks, print books, online databases, and research librarians ranked well below these newly emerging technologies. Fewer than one in five teachers said their students are “very likely” to use any of these sources in typical research assignments. In the case of online databases and printed books, half or more of the teachers who participated in the survey said their students are “not too likely” or “not at all likely” to use these sources. In fact, fewer teachers said their students are likely to use these sources than to use their peers, study guides such as SparkNotes or CliffNotes, or the websites of major news organizations.

When it comes to the use of print books, the findings across all subgroups in this sample of teachers are surprisingly consistent. Teachers of the poorest students—those living below the poverty line—stand out slightly in that they most commonly say their students are “very likely” to use print books in their research assignments (19% say this). Also among the teacher subgroups particularly likely to say their students are “very likely” to use print books in research assignments are middle school teachers (19%) when compared with 9th-10th grade teachers (12%) and 11th-12th grade teachers (11%). At the other end of the range, science (7%) and math (9%) teachers are particularly unlikely to say print books are a common source for their students.

Among the subgroups of this sample who are most inclined to say their students are “very likely” to use research librarians as a source are English teachers (20%) and teachers ages 55 and older (22%). But again, these figures are only slightly higher than the 16% of all teachers who say this is the case.

In focus groups, teachers noted that students prefer the internet because they find it a more interesting and entertaining platform. While the internet is a “cool” place to do research, other more traditional sources are perceived as “boring” by students. The internet offers multi-media content, links to additional information, interactive formats, and textbooks and other print books pale in comparison.

Traditional Textbooks are one-dimensional. They aren’t interactive. They don’t let me go somewhere else if I want more information. There’s no sound, no movies, no hyperlinks. Students are accustomed to interacting with text. I think that’s why textbooks on the iPad have been successful. – National Writing Project teacher

Last week, I gave my students twenty questions posed by the guys at Flocabulary in conjunction with the Wikipedia Blackout in Response to SOPA. The questions ranged from What is the State Bird of Arkansas” to “Who won Super Bowl X?” to “Who won the Republican primary last week?” Since the students could not use Wikipedia, it was interesting to see what they went to next: Ask.com, About.com. Dogpile.com, Google.com, Answers.com, and a host of other sites like these that are a part of my students’ collective toolbox when it comes to securing sources from the web. But when they were answering the one regarding the Super Bowl, none of the students in the six classes I teach ever thought to consult The National Football League. Further, when a question was posed about the first Starbucks, none of my students thought to ask anyone else in the room for their residential expertise. – National Writing Project teacher

Teaching students to do effective searches like SweetSearch.com helps them to understand that a discourse community does exist in regard to their selected subject and these parties often—well always—offer readily citable information wherein their traditional tried and true searches do not. – National Writing Project teacher

Students in my school setting know Yahoo and Google and as I have mentioned before, they think whatever they find on the internet is true. I teach my students to look at the initial source and see if they have any credible individuals to back up their research. Sometimes this is time consuming, but they do figure out there are bogus sites out there. I think students need to know there are people out there with websites just because they can have them. Students see the internet as a cool place where they can get quick information. They don’t know how to use it properly. I am not sure there are adults that know how to use it properly. – National Writing Project teacher

Teens are not alone in their reliance on search engines

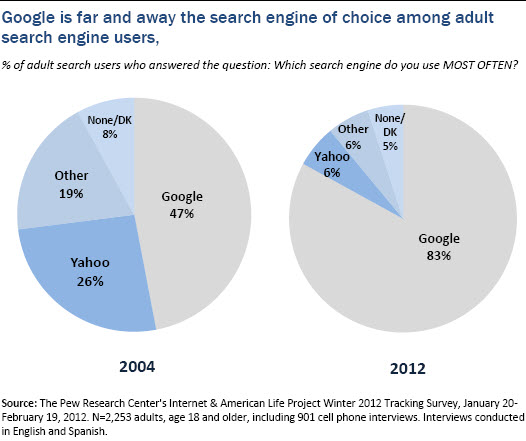

The trend among teens to equate finding information with “Googling” mirrors trends seen in adults over the past decade. Over time, Pew Internet’s surveys of adults have consistently shown that search engine use tops the list of most popular online activities, along with email. Currently, 91% of online adults use search engines to find information on the web, up from 84% in June 2004. On any given day online, 59% of those using the internet use search engines. In 2004 that figure stood at just 30% of internet users.9 Moreover, among adult search users, Google is far and away the most used search engine with Yahoo placing a distant second, and its dominance is growing over time.

Not only are adults increasingly reliant on search engines as an information resource, but they also report generally trusting the results they get and feeling the quality and relevance of the information provided by search engines is improving over time.10 Specifically:

- 91% of adult search engine users say they always or most of the time find the information they are seeking when they use search engines

- 73% of adult search engine users say that most or all of the information they find using search engines is accurate and trustworthy

- 66% of adult search engine users say search engines are a fair and unbiased source of information

- 55% of adult search engine users say that, in their experience, the quality of search results is getting better over time, while just 4% say it has gotten worse

- 52% of adult search engine users say search engine results have gotten more relevant and useful over time, while just 7% report that results have gotten less relevant

- 56% of adult search engine users say they are very confident in their search abilities, while only 6% say they are not too or not at all confident

- 86% of adult search engine users report that they have learned something new or important using a search engine that really helped them or increased their knowledge

- 50% of adult search engine users say they have found an obscure fact using a search engine that they thought they would not be able to find

In contrast, fewer adult search users report experiencing negative outcomes:

- 41% report getting conflicting information in search results and being unable to determine which information is correct

- 38% say they sometimes feel overwhelmed by the amount of information found using a search engine

- 34% feel that critical information is sometimes missing from search results

The teachers surveyed are likewise heavy search engine users, and are very confident in their searching abilities

The teachers in our sample are likewise part of the “Googling” trend. Asked about their own use of different online tools, 100% of the teachers participating in the survey said they use online search engines to find information online, with 90% naming Google as the search engine they use most often.

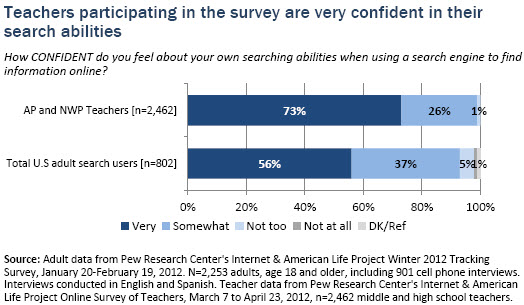

Overall, compared with all U.S. adults, this population of teachers is more confident in their own search abilities. Almost three-quarters (73%) of these middle and high school teachers say they are “very confident” in their own search abilities, with another 26% saying they are “somewhat confident.” Of the more than 2,000 teachers surveyed, only 1% describe themselves as “not too confident” when it comes to using search engines.

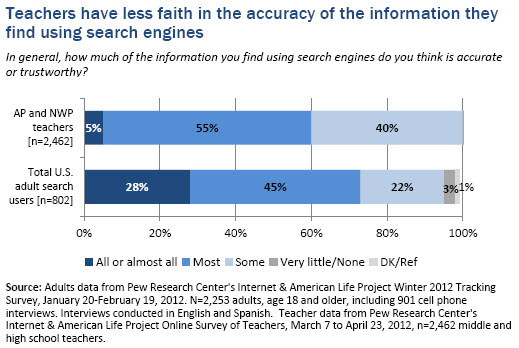

While this sample of AP and NWP teachers has greater confidence than adults as a whole in their search abilities, they have considerably less faith in the accuracy of the information they find using these tools. Just 5% of teachers participating in the survey say that “all or almost all” of the information they find using search engines is accurate or trustworthy, compared with 28% of all U.S. adult search users.

The AP and NWP teachers surveyed here are also very different from adults as a whole in that the youngest teachers have less faith in the accuracy of search results. Among the general population, younger adults tend to have more faith in the trustworthiness and accuracy of the search results they get. Yet teachers mirror the general adult population in that younger teachers have more confidence in their search abilities than their older counterparts:

- 50% of teachers ages 22-34 say that all or most of the information they find using search engines is accurate or trustworthy, compared with 61% of teachers ages 35-54 and 68% of teachers age 55 and older.

- Meanwhile, 80% of the youngest teachers say they are “very confident” in their search abilities, compared with 75% of 35-54 year-old teachers and 63% of teachers ages 55 and older.