Internet Access by Age, Health Status

Let’s map this mountain, starting with some bedrock data.

This is the known world of internet use in the U.S. which the Pew Research Center has been tracking for over 10 years. Think of us as your GPS for navigating the online world.

In order to get an accurate picture of a changing population we use national RDD telephone surveys, conducted in both English & Spanish and with a mixed sample of both landline and cell phones.

In 1995 only about 1 in 10 American adults had access to the internet. In 2000, it was up to nearly half of adults. Now, about 75% of adults and 95% teenagers in the U.S. have internet access.

One thing to keep in mind is the fact that adults living with chronic disease are significantly less likely than healthy adults to have access to the internet.

- 62% of adults living with one or more chronic disease go online.

- 81% of adults reporting no chronic diseases go online.

That’s one of the roadblocks to keep in mind. There are still pockets of people who remain offline, but many of them have what we call second-degree internet access. Their loved ones are online. Caregivers represent an opportunity for the engagement of our elders and other people who remain offline.

Wireless Access

Six in ten U.S. adults go online wirelessly, with a laptop, mobile device or tablet. A whopping 84% of 18-29 year-olds go online wirelessly.

Three key points about the wireless opportunity:

- Local: Nearly half of all American adults (47%) report that they get at least some local news and information on their cellphone or tablet computer. This is an example of how Pew Internet’s broad portfolio of research can benefit many fields. We are tracking the internet’s impact on politics, news, gaming, education, entertainment. The habits and behaviors that people form in those sectors will likely port over to health when someone gets sick – or is caring for a loved one.

- Health: wireless users are voracious information consumers, including some interesting trends within health – 48% of wireless users look online for information about doctors or other health professionals, compared with 31% of internet users who do not have wireless access, for example. The always-on, always-with-you internet becomes a default information source.

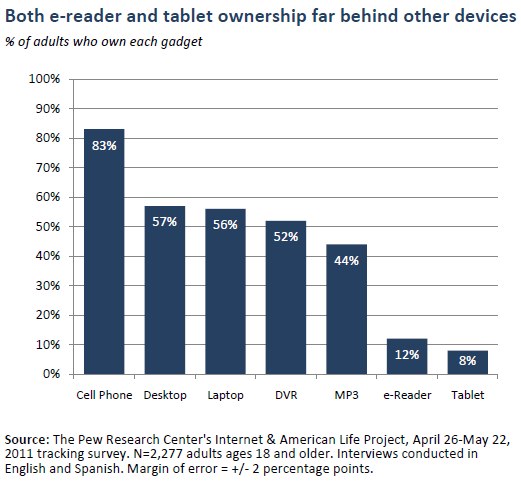

- Devices: 83% of American adults have a cell phone. Small screens outnumber big screens in the U.S. Ask yourself: are you doing everything you can to optimize for these small screens, for text messaging?

Smartphones

We recently came out with our first report focused on smartphones, a segment of that 83%. We find that 35% of American adults have a smartphone.

Our definition of a smartphone owner includes anyone who falls into either of the following two categories:

- cell owners who say that their phone is a smartphone.

- cell owners who say that their phone operates on a smartphone platform (these include iPhones and Blackberry devices, as well as phones running the Android, Windows or Palm operating systems).

One of my favorite survey questions is to ask people to describe something in one word because it’s a quick snapshot of how they feel, in their own words, not ours. When we asked smartphone owners to describe how they feel about their phones in a single word, here is what they said:

The three most common were “good, great, and convenient.” However, if you look closely, you can see “expletive” to the left of “love” on this slide.

Several demographic groups have higher than average levels of smartphone adoption, including:

- The financially well-off and well-educated.

- Those under the age of 45.

- African Americans and Latinos.

25% of smartphone owners say their phones are their main source of internet access. Fully 42% of smartphone owners between ages 18-29 say that. Many of these people have other choices, but they choose to access the web on their smartphone.

Here are three opportunities amplified by the rise of smartphones:

- Reach African Americans, Latinos, and young people.

- Make place irrelevant – otherwise known as Location-disabled – get the information out to everyone, no matter where they are. “I need this obscure information right now, even though I’m in the middle of nowhere” is location-disabled.

- Make place extremely relevant — otherwise known as Location-enabled – help someone in a certain place connect with local resources. For example, “where is the nearest clinic” is location-enabled. That’s what we see driving mobile adoption in many ways – hyper-local news and information.