Video of Susannah’s talk is available above and at the Transform Symposium’s website. A commentary based on her prepared remarks continues below.

Prepared for Mayo Transform 2010 : Thinking Differently About Health Care.

Ten years ago, I wrote the Pew Internet Project’s first report on the impact of the internet on health care, calling it “The Online Health Care Revolution.”

Back then, the idea that people were searching online for health information was revolutionary. All of a sudden, regular people had access to medical information that had always been locked up and out of reach.

Ten years later, I am ready to declare the access revolution over, at least in the United States. It’s time to change our frame of reference. Instead of talking about a revolution, our data shows that it is time to start building a new civilization. The Mayo Clinic was a leader during the revolution, opening up your expertise to the world. You can continue to be a leader if you take advantage of the trends I’m about to share.

First, some history.

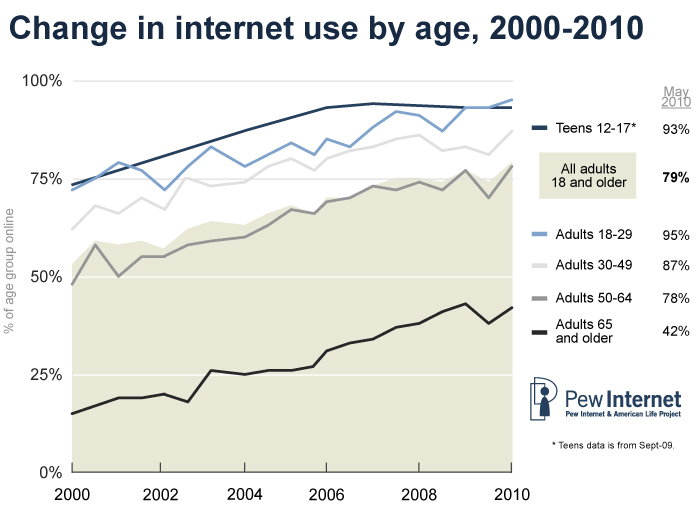

In 1995 only about 1 in 10 American adults had access to the internet. This was not that long ago. In 2000, it was up to nearly half of adults. Now, about 75% of adults and 95% teenagers in the U.S. have internet access.

Notice that lower line: the 65+ age group. There is a steady climb of internet users, from teenagers up to baby boomers, and then a cliff at about age 70-75.

There are still pockets of people who remain offline, the most significant group being our elders, but many of them have what we call second-degree internet access. Their loved ones are online.

In the year 2000 only 5% of households had broadband access. Now, two-thirds of Americans have broadband at home. Another revolutionary hurdle passed. One Pew Internet study found that dial-up users take part in an average of 3 activities per day. Broadband users take part in 7.

82% of American adults have a cell phone. Six in 10 American adults go online wirelessly with a laptop or mobile device.

Mobile was the final front in the access revolution. It has erased the digital divide. A mobile device is the internet for many people. Access isn’t the point anymore. It’s what people are doing with the access that matters.

Pew Internet research shows that mobile + broadband adds up to much more than 1+1. Each one has a multiplying effect on people’s behavior.

Let me give you some more context: How many of you remember your favorite class from your first year in college? Mine was Geology 101.

Our professor knew that very few of us were going to study rocks or soil samples, so he made it his mission to make us see the landscape in new ways.

His advice makes sense, and not just as a geologist: Know the history of the land you live on. Know that you can’t escape the reality of the landscape, but you can adapt to it.

Geologists are trained to take the long view, to notice patterns and to apply those observations in immediate, practical ways. That is essentially what I do today: I’m an internet geologist.

So where’s the action? What is causing the most radical landscape shift online? Wireless access.

Mobile devices are changing us, once again, as internet users, making us more likely to share, more likely to access information on the go, and, as I mentioned, erasing the digital divide. Once information is untethered, the oceans part and the landscape changes. We are now on the other side of a massive shift in communications.

In 10 years we have seen the internet go from a slow, stationary, information vending machine to a fast, mobile, communications appliance that fits in your pocket. Information has become portable, personalized, and participatory.

In fact, as we have watched the rise of wireless access, we’ve identified an effect that we’re calling “the mobile difference.”

Once someone has a wireless device, they are more likely to use the internet to gather information, share what they find, and create new content.

If your organization’s information is not available on a small screen, it’s not available at all to people who rely on their mobile phones for access. That’s likely to be young people, people with lower household incomes, and recent immigrants – arguably important target audiences for public health messages.

Mobile makes things personal. Mobile makes things immediate.

Just how immediate? One study in the Netherlands found that the average response time to a text is under 3 minutes. That’s an incredible opportunity. Let’s call it the FedEx principle. A FedEx arrives, you open it right away. A text message arrives, you open it. Text messages are personal, immediate, and tailor-made for calls to action.

For teenagers, you can multiply the FedEx principle by a factor of 10. Here is how this can be harnessed:

A team of Stanford researchers, working with Project HealthDesign, wanted to help chronically ill teenagers take more responsibility for their health.

In talking with teens, the researchers found that technology is a comfort, especially if it is portable, like an ipod or cell phone. They also found that teens are less likely to take their meds if they are feeling sad. So the researchers came up with a tool that tracks the teens’ moods, monitoring the songs they listen to and the words they use in text messages to friends and family.

And the teenagers agreed to surveillance? Yes. For two important reasons: #1, the researchers were a trusted entity. #2, it was a trade-off they were willing to make for better health and more independence from their parents.

The teens wanted to break the cycle of being in a bad mood, forgetting their meds, and catching hell. With the new tool, listening to sad songs or texting negative language triggers a medication reminder. The messages were seamlessly integrated into the teens’ lives, increasing their treatment adherence. And mom had nothing to do with it.

Treatment adherence is a huge challenge for health care today. Think about how the Mayo Clinic, another trusted entity, could harness a tool like this one. Look past the old conversations about privacy when you’re building on this new frontier. You may find creative solutions that get results.

On the other side of the age spectrum, the Pew Internet Project just released a report showing that older adults are flocking to social network sites, which is kind of a man bites dog story and made a lot of headlines.

But look at the uptake of these sites among young adults: 86% of internet users in their 20s use Facebook, MySpace, or LinkedIn.

Some of this data won’t be surprising to you, but we think it’s important to have the numbers, so we can look for new patterns.

For example, Pew Internet surveys show that social sites are becoming important hubs for health advice. People want to learn from each other, not just from institutions.

You might worry about people are giving each other medical advice. That’s got to be dangerous, right? So far, no. We’ve asked people in our surveys: Have you or someone you know been helped by health information found online? 60% of internet users who go online for health say yes, which is up from 31% in 2006. We’ve also asked: Have you or someone you know been harmed? That’s a flat-liner at 3%.

Here’s your opportunity: people are still often looking for, and linking to, authoritative source material. Make it easy and attractive for people to link to you. Seed the online conversation with data, with science, with evidence. You can’t control the conversation, but you can be part of it.

In addition to the “mobile difference,” by the way, we have also identified a “diagnosis difference.” Our research has found that internet users living with chronic disease are likely to be older and living in lower-income households – people who generally stay in the shallow end of the online activities pool. Email, search.

However if we control for all those other variables, living with chronic disease increases the likelihood that an internet user will say they work on a blog or contribute to an online discussion about health. They are learning from each other.

The rise of social networking shouldn’t surprise us. It is part of the history of our landscape. It is an ancient, communal ritual to talk with each other. The bottom line is that the internet widens your neighborhood, expands your networks, and speeds up the pace of conversation. And people say they feel better because of it.

In an online survey we conducted last year, one person shared: “I was having problems sleeping [because of] hip pain. Through this [online health community] I received information about proper ways to set up my bed and since then have been sleeping so much better.” A simple change, suggested by a peer, and it happened online.

Another respondent wrote, “I read the Gluten Free Forum daily for about a year before I really got my celiac disease under control and felt fully informed. You can’t call your gastroenterologist every time you buy a new product.” That’s where health care happens – in the grocery store aisle, making a decision, wondering what to eat for dinner tonight, looking up choices on a smartphone.

Think about what would happen if we could harness the instinct to share with the tools to make it easy.

About 20% of the online health population has posted comments or content related to health care. That’s the classic Pareto principle or 80-20 rule – 80% is listening, 20% is talking. But here’s where it gets interesting: hand someone a smartphone and they are more likely to become a contributor, a commenter, a creator. Mobile access bumps up participation.

What will happen when the untapped knowledge of every patient, of every caregiver, of everyone who has something of value to share actually has the opportunity to share it?

That’s the next frontier. It is no longer about access. It’s about uploads. It’s about inputs. It’s about learning from each other.

Patients are not the only ones who can benefit from this new model of participatory medicine. Institutions can too.

E-patient Dave deBronkart is a tech geek who also happens to be a cancer survivor. He used CaringBridge during his illness to stay in touch with his friends and family. He used ACOR to gather expert peer advice about kidney cancer. He used Beth Israel’s PatientSite to keep up to date on his treatments and communicate with his doctors.

So when Beth Israel announced a partnership with Google Health, Dave was among the first to press the button and allow his medical record to get sucked into Google Health’s online system.

Unfortunately, the system transmitted everything Dave had ever had – and a few things he’d never had. With almost no dates attached. It also sent through every medication Dave had ever been on, triggering a scary medication warning that was absolutely irrelevant and wrong since he hadn’t taken that drug for two years. Turns out that the system transmitted billing codes, not doctors’ diagnoses, and nobody had ever really looked at the results.

Well, until Dave blogged about it and his story was picked up by the Boston Globe.

As an internet geologist I’d have to say that Dave was a one-man earthquake, taking Google and Beth Israel by surprise.

The good news is that both Google Health and Beth Israel welcomed Dave’s critique and have made changes to their systems. But I bet they wished they’d done a test run with a group of patients before Dave published his post. Now Dave lectures around the world about how patients want to help and how patients want to be part of the new model: participatory medicine.

Let me wrap up with a couple of thoughts, going back to looking at the landscape and what it tells us.

The access revolution is over. Mobile is changing us, changing our frame of reference so that we see information as portable, personalized, and participatory.

Health care has a marvelous opportunity tap in to our ancient instincts to share and our modern ability to do so at internet speed.

Build on the new frontier. Build on the power of mobile.