Introduction

We asked respondents to think about the last time they went online for health or medical information, hoping to capture a portrait of a typical health search. As in past surveys,12 the typical online health information session is often undertaken on behalf of someone else, starts at a search engine, includes multiple sites, and has a minor impact on the person’s health care routine or the way they care for someone else.

Half of health searches are on behalf of someone else.

When someone gets sick, it is often the case that friends and loved ones help out by bringing food, taking care of household chores, or sending their best wishes. It seems that the internet provides another way for Americans to show the love: Serving as an online research assistant.

Forty-eight percent of health seekers say the last time they went online for health or medical information, their quest was related to someone else’s situation. Eight percent say their last search was for both themselves and for someone else. Thirty-six percent of health seekers say their last search was in relation to their own health or medical situation. Eight percent say they do not remember or did not answer the question.

Parents are more likely than non-parents to look for health information on behalf of someone else: 54% of health seekers with a child under 18 living at home did their last health search on behalf of someone else, compared with 44% of health seekers who do not have children living at home.

Two-thirds of health information queries start at a search engine.

In 2005, the Pew Internet Project reported that search dominates the typical online day and internet searchers’ success generates a remarkable sense of confidence and trust in search engines.13

This study builds on those findings by showing that 66% of health seekers say their last query began at a general search engine like Google or Yahoo. Twenty-seven percent of health seekers say their last health information session began by going to a specific website they know provides health information and 3% volunteered that it began some other way. Five percent of health seekers do not remember or did not answer the question.

Younger health seekers are the most likely age group to start at a search engine. Three-quarters (74%) of health seekers age 18-29 started at a search engine, compared with 65% of e-patients age 30-49 years old. Older health seekers are the most likely age group to start at a specific website they know provides health information: 34% of those age 65 and older did so.

There is a new crop of medical search engines which hope to change the way internet users approach health information online, but since they are so new we did not include them in our survey. Some examples of these “vertical” search engines include: Healthline.com, Healia.com, Kosmix.com, Mammahealth.com, and Medstory.com but the industry also awaits word on Google’s plans for expanding this category of search.

Most visit two or more sites in a typical health information session.

The great majority of health seekers visited at least two websites the last time they got health information online. Only one in five (22%) health seekers say they visited one site. Forty percent say they visited two or three sites. Another fifth of health seekers (21%) visited four or five sites during their last health information session. Eight percent visited six to ten sites and 2% visited between 11 and 20 sites. A stalwart 1% of health seekers visited more than 20 sites the last time they sought health information online. Six percent of health seekers do not remember or did not answer the question.

One-third later talked to a doctor about what they found online. Two-thirds did not.

One of the concerns that the medical community expresses about online health seekers is whether they are self-diagnosing and self-medicating based on the material they find online and without consultation with medical experts. It has probably always been the case that people do not discuss every book, magazine article, or health-related conversation with their doctor. But interest in the typical online health information session persists. This study finds that 33% of health seekers later talked with a doctor or other health professional about the information they found online during their most recent search. Sixty-six percent of health seekers did not talk with a health professional.

In our survey, e-patients whose last search was on behalf of themselves were more likely than those who searched on behalf of someone else to later talk with a doctor about what they found (42% vs. 31%). This makes sense; an internet user might deliver a packet of online health research to a loved one and not accompany that person to her doctor’s appointment to discuss the material.

Indeed, those who have had relatively recent contact with doctors are more likely to have discussed online health information with them. Thirty-five percent of health seekers who have seen a doctor in the past year discussed what they found online during their last health information session with a health professional, compared with 23% of those who have not visited a doctor in the past year.

An April 2006 article in the journal Preventing Chronic Disease provides an interesting comparison to our question about a respondent’s most recent health-related query by asking a more general question. Fifty-three percent of e-patients in their survey said they “sometimes” shared the information they find online with their doctors.14

Doctors may play a role in an e-patient’s decision to bring up online health information during a clinical conversation. Marc Siegel, an internist and associate professor of medicine at the New York University School of Medicine, recently wrote about his own attitudes toward “know-it-all” patients. A series of bold e-patients who insisted on being partners in their care inspired a profound realization: “Whatever the source of a patient’s information, a physician is most effective when he or she isn’t defensive, but acts as an interpreter of information and guide of treatment, leaving the ultimate control to the patient.”15 Doctors who do not reach this conclusion may feel the effects of a changing market. Our 2003 report, “Internet Health Resources,” chronicled the way some e-patients respond to doctors who reject their online research: They leave that doctor’s practice if they can.

Half of health searches have an impact on the person’s own health care routine or the way they care for someone else. But only one in ten health seekers say the effect was major.

Forty-two percent of health seekers report that the health information they found in their last search online had a minor impact on their own health care or the way they care for someone else. Eleven percent of health seekers report a major impact. Forty-two percent of health seekers report that the information they found in their last search had no impact at all on their own care or how they help someone else.

The impact was most deeply felt by internet users who had received a serious diagnosis or experienced a health crisis in the past year, either their own or that of someone close to them. Fourteen percent of these hard-hit health seekers say their last search had a major impact, compared with 7% of health seekers who had not received a diagnosis or dealt with a health crisis in the past year.

A study of 498 newly diagnosed cancer patients published in the March 2006 Journal of Health Communication measured the internet’s impact on people facing a health crisis.16 Patients who used the internet to gather health information were more likely than non-users to be confident about participating in treatment decisions, asking questions, and sharing feelings of concern with their doctors. However, the impact is not always positive according to a July 2006 article in The Oncologist: “[T]he risks associated with the use of the internet as an information source for and retailer of [complementary and alternative medicine], whether as preventive, curative, or palliative treatment, should be more explicitly brought to the attention of cancer patients.”17

In our survey, 53% of health seekers reported some kind of impact. This group was asked a series of follow-up questions to elucidate the information’s consequence. Since health information can have multiple effects on people’s behavior and decision-making, we allowed multiple responses.

Among the internet users who say their last search had either a major or a minor impact:

- 58% say the information they found in their last search affected a decision about how to treat an illness or condition.

- 55% say the information changed their overall approach to maintaining their health or the health of someone they help take care of.

- 54% say the information lead them to ask a doctor new questions or to get a second opinion from another doctor.

- 44% say the information changed the way they think about diet, exercise, or stress management.

- 39% say the information changed the way they cope with a chronic condition or manage pain.

- 35% say the information affected a decision about whether to see a doctor.

In general, few say they are harmed and many are helped by following medical advice or health information found on the internet.

In addition to the impact felt by their last online health information search, 31% of health seekers say they or someone they know has been significantly helped by following medical advice or health information found on the internet. That translates to about 35 million adults who report knowing about a significantly positive effect. Just 3% of health seekers, or about 3 million adults, say they or someone they know has been seriously harmed by following the advice or information they found online.

These findings build on previous Pew Internet & American Life Project surveys which have found that the vast majority of health seekers say the benefits of online information outweigh the risks. In a February-March 2005 survey, we asked respondents first whether they had helped someone deal with a major illness or health condition within the past two years and, if they had, whether the internet played a crucial role, an important one, a minor role, or no role at all in this event. E-caregivers who said the internet played a crucial or important role were then asked if they got bad information or advice online that made their experience more difficult. Six percent of these respondents said yes; 91% of e-caregivers said that was not a problem for them.18

Health seekers feel mostly reassured, confident, and comforted by what they find online.

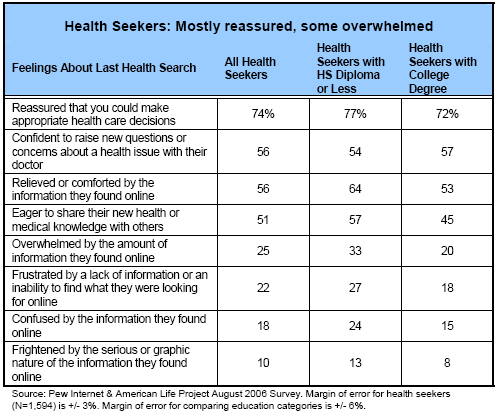

We gave respondents eight different ways – four positive and four negative – to describe how they felt during their last search for health information online. People were much more inclined to identify with the positive descriptions. By far the most popular choice read as follows: “At any point, did you feel reassured that you could make appropriate health care decisions?” Fully 74% of health seekers said yes, that described how they felt during their last online health information session.

In addition:

- 56% say they felt confident to raise new questions or concerns about a health issue with their doctor.

- 56% say they felt relieved or comforted by the information they found online.

- 51% say they felt eager to share their new health or medical knowledge with others.

On the other hand:

- 25% say they felt overwhelmed by the amount of information they found online.

- 22% say they felt frustrated by a lack of information or an inability to find what they were looking for online.

- 18% say they felt confused by the information they found online.

- 10% say they felt frightened by the serious or graphic nature of the information they found online.

Health seekers with a high school education or less are more likely than those who graduated from college to say they were relieved or comforted by the information they found online during their last health query. Health seekers with a high school education or less are also more likely than those with a college degree to say they felt eager to share their new health or medical knowledge with others. Yet health seekers with less education are also more likely than college graduates to express negative feelings about the information they found online (see chart below).