The internet’s role in campaigns has grown dramatically since 2000.

There are several forces driving people’s increased use of the internet for getting general news and for getting political news in particular:

- There is a growing number of broadband users. The figure has jumped more than ten-fold since June of 2000, when the Pew Internet Project began to ask whether online Americans had a high-speed connection in their homes. Always-on broadband connections make it easier for people to get news online because they don’t have to take the extra step of connecting first and because they can move more quickly around the internet while they are browsing for news.

- Online experience often leads people to discover they can do more and more online, including accessing news. More than 80% of U.S. internet users now have at least three years of internet experience, and more than half have more than six years experience.

- Many people now expect they can get up-to-date news online and they have become more likely to “check” the headlines every so often while online, just as they tune in to news-radio at the top of the hour.

- Many Web sites offer news and headline services, even sites that are not primarily news sites. Moreover, many news organizations now offer email headline alerts or RSS feeds of their material. It is hard to be online very long without bumping into news.

- The internet has woven itself into political discourse because people are increasingly likely to use email to “discuss” politics, or joke about candidates, or forward news tidbits or funny clips about politics.

- There were other factors related to greater interest in this race that had nothing to do with the internet, but perhaps made the internet a more valuable means of gathering political information. Many people believed this was a close and very important political election and that brought a great deal of interest to the race, including interest in online sources of news and information as politics.

With all that as background, this section of the report will cover the new contours of the online political landscape.

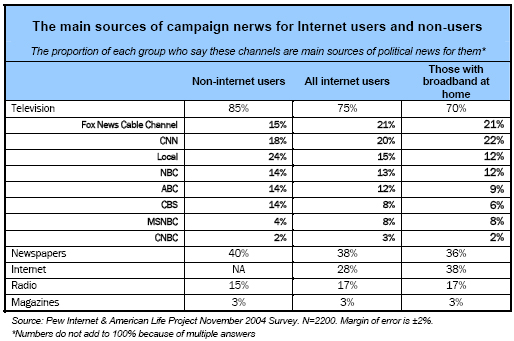

For online Americans, the internet has drawn even with radio as a source of campaign news.

Television is substantially ahead of other media as a primary source for campaign news for Americans. Fully 79% of all Americans – internet and non-internet users alike – said that television was the place where they got most of their news about the campaign. At the same time, the internet has gained a major footing in the media-plex. One in six Americans (18%) said the internet was a main source of campaign news for them, a nearly six-fold increase from the proportion of population who said that in 1996.

Moreover, the internet has caught up to radio and is closing in on newspapers as a primary political news source among those who go online. Fully 28% of internet users said the internet was a primary source of news for them, compared to 17% who said radio was a main source of campaign news for them. The figures in the table below show something the Pew Internet Project has seen in survey work in other contexts of news gathering. Many internet users go online for news and information that supplements or expands the information they are getting from other sources.

For those with broadband connections at home, the internet has become a source of political news that is equally important as newspapers. And for those who are surrounded by broadband connections – those with high-speed links at home and at work, or about 14% of the overall U.S. population — the internet is far more important for political news than are newspapers. Fully 51% of those with broadband at home and work say the internet is the main source of news, compared to 33% of them who say newspapers are their primary source and 66% who say television is their primary source.

75 million Americans used the internet in campaign 2004 for political purposes.

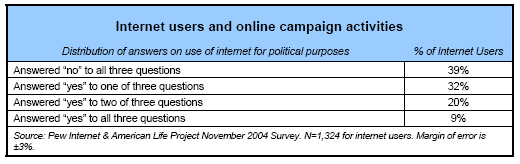

We calculate the overall online political population by asking about three separate dimensions of political life. First, we ask whether internet users got news or information online about the campaign. More than half of internet users (52%) said they had gotten political news and information via the internet and that represents more than 63 million people. This is an 83% spike in political information gathering online from the 2000 race, when about 34.5 million people used the internet that way.

Second, we asked about people’s email use. Did they send or receive emails about candidates or campaigns? More than a third of internet users (35%), or about 42 million people, said they had used email this way. This is the first campaign during which we asked that question, so there are no comparative earlier data on it. Moreover, 14% of internet users told us they had sent emails discussing politics via listservs or group lists of family members, friends, or associates.

Third, we asked, “Have you participated in any other campaign-related activities using the internet, such as reading discussion groups, signing petitions, or donating money online?” Some 11% of internet users, or 13 million people, engaged in campaign-related activities of this type.

61% of internet users said they had either gotten campaign information or news online, exchanged email about the campaign, or participated in campaign-related activities such as making an online donation.

Any internet user who said “yes” to one of those three questions is considered part of the online politics user community in our calculations. That came to 61% of internet users or 75 million people. In fact, many people said “yes” to two or all three of the questions.

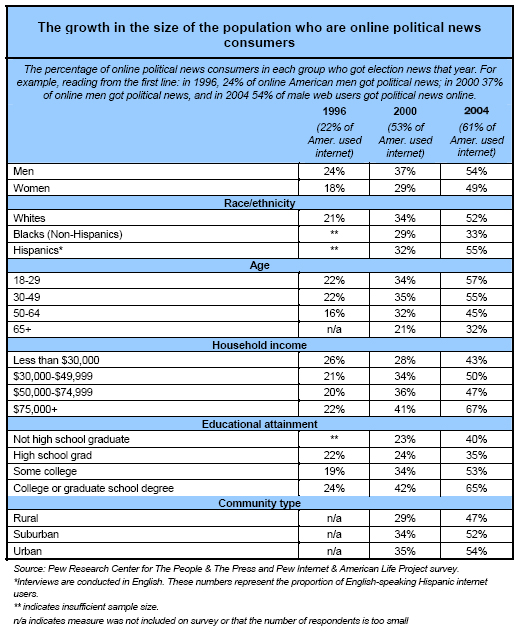

The pool of online political news consumers has grown and become more mainstream in some ways since the early days of the internet.

As the internet has become a popular technology adopted by a majority of American adults, its demographic character has changed and that has led to changes in users’ motives for getting political news online and their preferences in the Web sites they access for political news. At election time in 1996, internet adoption stood at 22% of the U.S. population and the online political news audience was disproportionately male, white, and relatively well-to-do.

By 2004, 61% of American adults were online and the population was evenly split between women and men and contained far higher proportions of minorities, older Americans, less well-educated and less financially well-off Americans.

These changes were also reflected in the online political news audience. For instance, over time, the number of women grew and their proportion in the online political news audience grew to 47% in 2004, from 34% in 1996. Similarly, the proportion of non-whites grew from 18% of the online political news audience in 1996 to 23% in 2004; the proportion of those over 50 in that audience doubled from 10% in 1996 to 22% in 2004; and the proportion of rural residents grew from 17% to 21% over that time span.

Among other things, this shift in population composition made the online political news consumer population a bit more casual as a group about political news, more likely to cite convenience as a primary reason to get political news online and more likely to visit the sites of traditional news organizations.

Mainstream sources dominated the online news and information gathering by online Americans. At the same time, alternative news sources mattered to one in four political news gatherers.

Asked where they went online most often to get news and information about the campaign, the majority of internet users reported they went to sites of traditional news organizations or online services that syndicate news from traditional sources, such as wire services. It is important to stress, though, that the absolute number of online Americans using each kind of Web site grew dramatically from 2000 to 2004. As we noted above, the number of those who got political news online grew from 34.5 million to 63 million in that four-year span.

One in five of those who used the internet to get campaign news (20%) in 2004 identified CNN.com as the single source they used the most. Some 10% said they relied most on AOL; 10% said MSN; 8% said Yahoo; 5% said MSNBC’s Web site; 5% said Fox News’s Web site; 4% said local media; 3% said the New York Times; 3% said Google news; and 1% said Drudge Report.

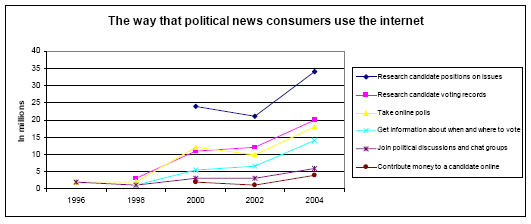

Online citizen action increased across all six categories tracked.

The internet has made it easy for political audiences to take citizen action, both in response to prompts from campaigns and on their own initiative. It also has become a valuable resource for many as a fact-checking mechanism, a tool to find out what a variety of political actors (such as interest groups) are doing, and a way to get “insider” information that used to be the province of small numbers of political junkies. Finally, there were extensive get-out-the-vote operations by both partisan and non-partisan organizations, and many of these operations had a powerful online presence. All of this translated into more online political activity in 2004 than in 2000.

Given an expanded internet population, the rise in broadband connections, advances in online campaigning, and the excitement of the Bush-Kerry race, one would expect gains in citizen activity levels between 2000 and 2004. In raw numbers, this was indeed the case for each of the six types of participation we surveyed in both campaign cycles:

- Voting information: The number who got information on where to vote grew more than 150% to nearly 14 million people.

- Donations: The number who gave campaign contributions online grew 80% to about 4 million people.

- Discussion and chat: The number who participated in online political discussions or chat groups grew 57% to about 4.5 million people.

- Candidates’ voting records: The number who got information about candidates’ voting records grew 38% to nearly 16 million people.

- Surveys: The number who participated in online surveys about politics grew 15% to just under 14 million people.

- Candidates’ positions: The number who researched candidates’ positions online grew 14% to more than 27 million people.

In addition, we asked about several new types of online political activities in this presidential election cycle. We found that —

- 32 million people traded emails with jokes in them about the candidates.

- 31 million went online to find out how candidates were doing in opinion polls.

- 25 million used the internet to check the accuracy of claims made by or about the candidates.

- 19 million watched video clips about the candidates or the election.

- 17 million sent emails about the campaign to groups of family members or friends as part of listservs or discussion groups.

- 16 million people checked out endorsements or candidate ratings on the Web sites of political organizations.

- 14 million signed up for email newsletters or other online alerts to get the latest news about politics.

- 7 million signed up to receive email from the presidential campaigns.

- 4 million signed up online for campaign volunteer activities such as helping to organize a rally, register voters, or get people to the polls on Election Day.

Those who get political information online split into two distinct camps: those who find it a convenient way to get information, and those who don’t think they get all the information they need from newspapers or TV news.

One of the continuing stories of the campaign involved the news media itself. The 2004 campaign saw a dramatic rise in the number of political bloggers and other online activists who critiqued, challenged, and cajoled reporters from traditional news organizations. Some 33% of those who used the internet for political purposes said they did so because they did not get all they wanted from their newspapers and television news. Another 11% said they most liked getting political news on the internet because they can get information on the Web that is not available elsewhere. At the same time, 58% said they went online for political information because it was convenient.

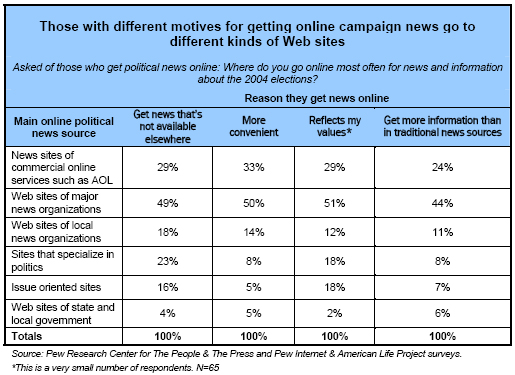

Those who cited convenience as the main reason they got political news online were more likely than others to get news from the news section of their internet service provider, such as AOL and MSN, or mainstream news organization sites, especially those run by cable news stations or a local newspaper or TV station. At the same time, those who cited the extra advantages of getting news online (more depth or different sources) were more likely than others to go to political sites, issue-oriented sites, alternative news sites such as the Drudge Report, and blogs.

Those citing the particular advantages of getting news online were especially interested in getting information about candidates’ positions, their voting records, and the endorsements or candidate ratings of political organizations. They were also more likely than others to use the internet as a reference to fact check the accuracy of claims made by or about the candidates.

Internet users often bumped into political news when they were doing other things online.

One of the realities of life online is that an internet user can encounter material through links or through general browsing that is often not related to the subject that inspired them to go online in the first place. For instance, they might go online to check the weather or find out when a movie is playing at a local theater and encounter political information that is also displayed on the site they are using.

Fully half of internet users (50%) said they encountered political news by happenstance browsing during 2004. This was most likely to happen to broadband users, who tend to spend the most time online, and to younger internet users.

Voters aren’t always looking just for information that supports their point of view. There are many active contrarians in the online population.

One of the major concerns about people’s use of the internet is that they might use the powerful filtering mechanisms available online and begin to shun information that does not agree with their beliefs. The Pew Internet Project studies the phenomenon of “selective exposure” in a recent report, which found that it does not appear to be a typical pattern of internet users.4 This new survey provides additional support for the idea that internet users are likely to encounter contrary information.

Asked about the Web sites they regularly visit, a plurality of internet users said they prefer neutral sources; the remainder divided evenly between preferences for sites that agreed with their political views and sites that challenged their political views. Some 31% said they get most of their information from sites that do not have a particular point of view. However, 26% report they go to sites that share their point of view, and 21% say they go to sites that challenge their point of view. A fifth of those who got political information this past year did not answer the question about the point of view they get from the Web sites they use most. Interestingly, there are no significant partisan differences on this question. Bush and Kerry backers are equally likely to say “yes” to each of the alternatives.

Online Americans give a positive verdict about the overall role of the internet in the campaign.

To many Americans 2004 seemed to be a rough-and-tumble election, and we wondered if internet users had an overarching view of the role the internet played in the conduct of the campaign. Half of online Americans (49%) and 56% of those who got political news online said, “The internet has raised the overall quality of public debate,” and only 5% said the internet lowered the quality of the debate. Some 36% said the internet did not make much of a difference.

The positive views were spread equally across the partisan landscape. Kerry partisans, Bush backers, liberals, conservatives, Republicans, and Democrats pretty much shared the same judgments. The most active internet users were the most likely to have upbeat views about the role of the internet. Fully 65% of those with broadband at home and work shared the view that the internet helped the debate. And those with lots of experience online were twice as likely as relative newcomers to express positive views about the role of the internet.

40% of internet users say the internet was important in giving them information that helped them decide their vote. And 20% say internet information made a difference in their voting decision.

Four out of ten internet users said the internet was very important (14%) or somewhat important (26%) in providing information that helped them decide their vote. Among those who actually got political news and information online, fully 52% said the internet was important: 19% said it was very important and 33% said it was somewhat important.

Some 18% of internet users said the political information they got online encouraged them to vote and only 1% said it discouraged them from voting. Among those who got political news and information online, 23% said the information they got encouraged them to vote.

When it came to their own voting decision, 20% of all internet users and 27% of those who got political news online said the information they encountered online helped them decide which way to vote.