The internet became an important factor during the 2004 campaign.

The internet’s distinctive role in politics has arisen because it can be used in multiple ways. Part deliberative town square, part raucous debating society, part research library, part instant news source, and part political comedy club, the internet connects voters to a wealth of content and commentary about politics.

As recently as early 2003, when the Pew Internet & American Life Project reported on the use of the internet by citizens and campaigners in the 2002 midterm election campaigns, it was still not very clear whether there would be major roles for internet users to play in politics. Today, just two years later, at least three such roles have emerged:

- Absorbing, sharing, and talking about politically significant pieces of content. The internet became a medium for circulating all kinds of information about the 2004 campaign, including a lot of off-beat and non-traditional information that found its way into the mainstream media coverage and the ongoing campaign debate after first gaining traction online. For example, online photographs of a mysterious bulge under the President Bush’s suit coat during one of the debates and online audio remixes of Howard Dean’s “scream” on the night of the Iowa caucuses gave these two campaign episodes more attention than they might otherwise have had. The internet was also the venue for voluminous reports and commentary about President Bush’s National Guard service and John Kerry’s Vietnam service. Bloggers were especially prominent distributors and interpreters of this sort of political content, but email and message boards contributed to the buzz factor as well.

- Soliciting and donating money for campaigns. The internet proved an effective medium to raise large amounts of money in small donations from many people on a recurring basis. The Howard Dean campaign collected over $20 million through the internet, a remarkable 40% of its total receipts. The Kerry campaign amassed $82 million of its $249 million online (33%), while the Bush campaign, which did not go at internet fundraising with the same intensity or success as did the Democrats, collected $14 million of its $273 million online (5%).2 Much of this online money came in donations under $200, an important development with implications for the perennial debate over the influence of big money on American politics, as well as for the attainment by the Democratic national party of financial parity with the Republicans.

- Fine-tuning, coordinating, and executing the “ground war” of voter contact. The internet facilitated greater precision in campaign targeting at each stage of the get-out-the-vote (GOTV) process: locating likely supporters, establishing communication lines with them, delivering messages to them, affording them opportunities to help the campaign, and making sure that they registered and cast their ballots. The Dean campaign discovered that Meetups, physical meetings arranged through the online services of a private company, were excellent venues for supporters to coalesce into local campaign teams. Then the campaign deployed its own “Get Local” software to enable and encourage supporters to set up house parties, a grassroots organizing device the Kerry and Bush campaigns emulated and refined. The nominees, along with the parties and numerous advocacy groups, relied on databases to identify voters and on local volunteers to update the data. Home visits, phone calls, email, and even advertisements were delivered to individuals, not just to precinct blocks.

Where the mediascape stands

The internet entered the political media and communications world at a time when it was already in great ferment. The Pew Research Center for The People & The Press has documented how news audiences have become increasingly politicized, as trust in the mainstream media has declined and public perceptions of the credibility of mainstream news sources has fallen.3 Audiences have been fracturing and the internet is playing an ever-more-important role.4

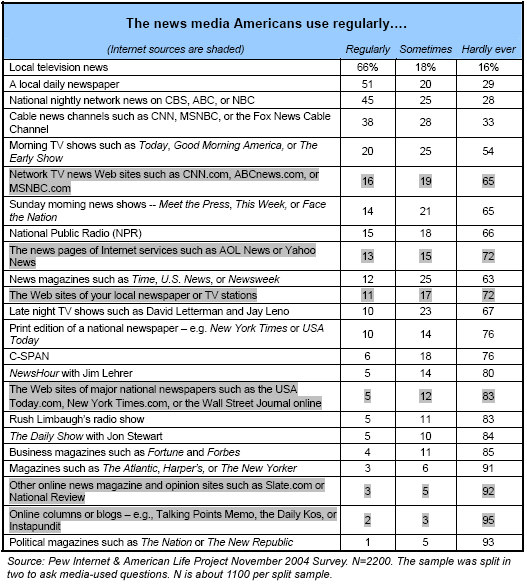

The table below shows the contours of the general media universe at the end of the 2004:

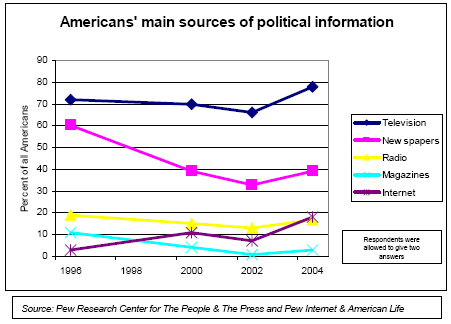

Nearly one in five Americans now say the internet is a main source of their political news and information.

And most significant has been a six-fold increase in the percentage of Americans citing the internet as their prime news source since 1996, from 3% of the population then to 18% now.

The daily audience for general online news grows and the appetite for political news from internet sources leaps.

This pattern in getting political news online emerges from a broader trend: more and more internet users go online to get all kinds of news. On a typical day during the final weeks of the campaign, there was a general increase in the number of internet users who get news online – not just political news, but all kinds of news. Nearly a third (31%) of internet users, or 37 million Americans, were getting news online. That is about 15% higher than the general online news audience from the middle of the year. And it represents growth of nearly 75% in the daily online news audience from the middle of 2000.

Some 17% of internet users, or about 20 million people, were online getting political news each day as the campaign drew to a close. That is an increase of 54% from the number of people who were getting political news on average days during the final stages of the 2000 presidential contest. All told, 58% of internet users said that at one time or another they get political news online, a 29% increase over the number who said they got such news in 2000.

Almost two-thirds of all Americans were contacted by the campaigns and political activists in the race’s home stretch.

Candidates, political groups, and activists were particularly aggressive in their mobilization and get-out-the-vote efforts in 2004. Nearly two-thirds of all Americans (64%) were contacted directly by political actors in the final two months of the campaign.

About half the entire adult population (49%) got politically related mailings during the period between Labor Day and Election Day; 40% received phone calls; 14% received emails; and 9% were visited at their homes. Interestingly, there were no partisan differences in these contacts. The Kerry and Bush campaigns were equally likely to have made contact with voters using each of those methods. And many people heard from representatives of both camps by mail, phone, or email, or on their doorsteps.

Millions were directly involved in political activity.

More than a quarter of Americans (26%) were themselves involved with campaigns, campaign events, or direct political mobilization efforts. And 81% of all American adults were contacted by others during the last two months of the campaign by those connected to the candidates – either by mail, email, phone, or house visits.

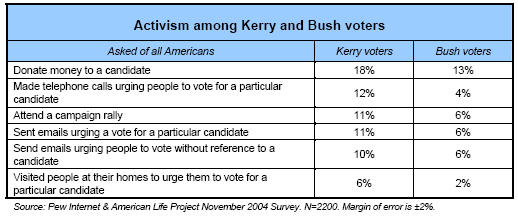

Some 11% of Americans gave money to a political candidate; 7% attended campaign rallies; 7% sent emails urging people to vote; another 7% urged others through email to vote for a particular candidate; 6% made phone calls on a candidate’s behalf; and 4% did door-to-door canvassing. Kerry supporters were more likely than Bush supporters to have done each of those campaign activities.

On the receiving end, 49% of all Americans received mail urging their vote for a particular candidate, 40% received candidate-supporting phone calls, 14% received emails, and 10% were visited in their homes.

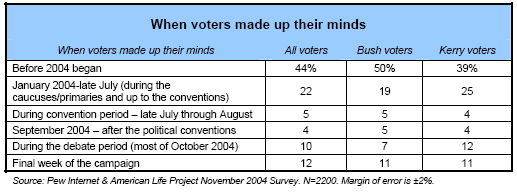

Different voters made up their minds at different times.

One of the factors that probably influenced people’s interest in getting political information relates to the timing of their voting decision. Those who make up their minds early probably have less of a need to gather news and information about politics than those who are in the throes of making up their minds.

There was a clear partisan pattern in the timing of voting decisions: Bush voters were more likely than Kerry voters to say they made up their minds early. Kerry voters said they knew later in the cycle and support for him came in several identifiable waves.