Two-thirds of those who download music files or share files online say they don’t care whether the files are copyrighted or not; 35 million U.S. adults download music files online, 26 million share files online

The struggle to enforce copyright laws in the digital age continues to be an uphill battle for content owners. Data gathered from Pew Internet & American Life Project surveys fielded during March – May of 2003 show that a striking 67% of Internet users who download music say they do not care about whether the music they have downloaded is copyrighted. A little over a quarter of these music downloaders – 27% – say they do care, and 6% said they don’t have a position or know enough about the issue.

The number of downloaders who say they don’t care about copyright has increased since July-August 2000, when 61% of a smaller number of downloaders said they didn’t care about the copyright status of their music files.

Of those Internet users who share files online (such as music or video) with others, 65% say they do not care whether the files they share are copyrighted or not. Thirty percent say they do care about the copyright status of the files they share, and 5% said they don’t know or don’t have a position.

Background

Americans’ attitude towards copyrighted material online has remained dismissive, even amidst a torrent of media coverage and legal cases aimed at educating the public about the threat file-sharing poses to the intellectual property industries. Consumers argue, in some news reports, that downloading simply supplements their regular music purchasing habits or serves as a form of sampling new music. Some consumers have also been quoted as saying that the prices of CDs and DVDs are too high with too little profit going to the artists, while others say the music they want simply isn’t available offline because it is out-of-print or otherwise hard to find. Still others say that they are entitled to make “fair use” of the music they purchase by sharing it with friends over these networks.

Whatever the argument, it is clear that millions of Americans have changed the way they find and listen to music. When we last issued a report on the growing popularity of downloading music online in 2001, the legal battle to protect copyright was focused on the efforts of the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) to challenge large file-sharing networks like Napster. Though the RIAA won its case against Napster and effectively forced the site to shut down in 2001, a myriad of decentralized file-sharing services emerged and millions of Internet users simply migrated to the new systems. In all, the recording industry attributes a 25% drop in CD sales since 1999 to online piracy. However, some have disputed this notion, citing a slumping economy, rising CD prices and fewer titles being released.

This year, the RIAA lost an important case against the makers of the Morpheus and Grokster peer-to-peer software when a federal judge in Los Angeles ruled that the file-sharing software itself was legal, even if it was being used to distribute illegal copies of copyrighted music and movies. The court ruling prompted a shift in the RIAA’s tactics from suing file-sharing companies to targeting individuals who allegedly use file-sharing software to download and share copyrighted material.

In January 2003, the RIAA won a landmark case against Verizon, forcing the company, under the provisions of the 1998 Digital Millennium Copyright Act, to release the names of subscribers who were suspected of copyright infringement. Verizon appealed the ruling, citing customer privacy concerns and the lack of court oversight required for the subpoena process. However, the ruling was ultimately upheld and paved the way for the recording industry and other copyright holders to begin suing individuals believed to be infringing on copyright protections.

As of July 28, 2003, the RIAA has sent out close to 1,000 subpoenas requesting information from Internet Service Providers in order to identify and contact customers who are potential copyright infringers. The lobbying arm of the recording industry has said it would focus its subpoena campaign on users who were allowing a “substantial” number of files to be shared from their computers. However, some users claim they are unaware that they are making their files available to others because programs like KaZaA include default settings that automatically allow sharing with others on the network. Other users say they have assumed that because Napster was shut down, any file-sharing service that remained in operation must only permit legitimate or “fair” uses. However, while Napster was unsuccessful in using a fair use defense in its case, it remains to be seen how successful this line of defense will be for the cases involving individual Internet users.

In addition to the lawsuits being filed by the RIAA, two pieces of federal legislation were introduced that are intended to curb the illegal use of file-sharing networks. The Piracy Deterrence and Education Act of 2003 (HR 2517), sponsored by Lamar Smith (R-Texas), proposes warning, education, and enforcement programs that would require the involvement of the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Department of Justice. The Author, Consumer, and Computer Owner Protection and Security Act (HR 2752), proposed jointly by John Conyers (D-Michigan) and Howard Berman (D-California), would impose criminal penalties of up to five years in prison for online copyright infringement. Additionally, it proposes an allocation of $15 million to the Department of Justice to enhance domestic and international enforcement of copyright laws.

Downloading population grows conservatively

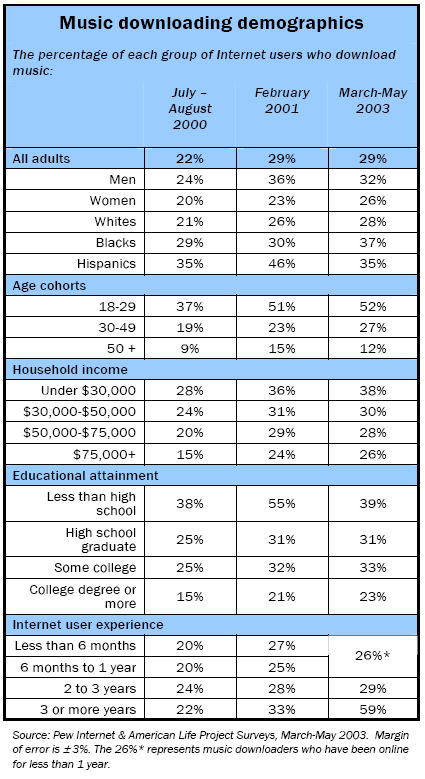

In a Pew Internet & American Life Survey fielded between March and May of 2003, the Project found that 29% of Internet users have “downloaded music files to their computer so they can play them any time they want,” and about 4 percent of Internet users do so on an average day.

This 29% is the same portion of Internet users who were downloading music files when we released our “Music Downloading Deluge” report in April 2001, but represents a larger number of people due to the overall growth of the online population that occurred between 2001 and 2003. In April 2001, we reported that the downloading population consisted of roughly 30 million American adults, but our 2003 data shows that number has risen to 35 million.

File-sharers are almost as abundant as downloaders, with considerable overlap between the groups

Some 21% of current Internet users say they share files – they allow others to download files, like audio or video files, from their computers.1 But the vast majority of online Americans, 78%, do not share files online with others.

Some users choose to make files available for download by posting the audio files online themselves. This might consist of a band posting a song online for promotional purposes or a fan posting a song to share with friends. In all, 5% of all Internet users say they have posted audio files to the Internet themselves.

Not surprisingly, there is considerable overlap between the downloading and sharing populations. Within the downloading population, some 42% of those who download files say they also share files with others. Peer-to-peer file-sharing networks are built upon the premise that users will both give and take copies of files from the collective pot. However, it is likely that users will be more conservative about sharing music files in the near future for fear of legal ramifications. What is less predictable is whether users will then buy the music they are not able to access online for free.

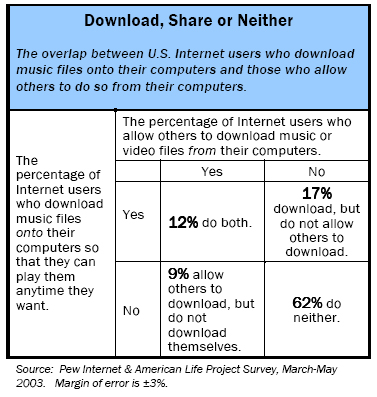

Currently, when looking at the overall Internet population, those who strictly download already outnumber those who both download and share. Out of all Internet users, 17% download music but do not share files online, 9% share files online but do not download music, 12% both download music and share files, and 62% do not download music or share files at all (see table).

Who is doing the downloading?

Though the size of the downloading population has grown in two years, its basic demographic composition has not changed much. Male Internet users are more likely to be downloaders than women by a modest margin (32% vs. 26%). African-Americans and Hispanics are also more devoted downloaders than their white counterparts, with 37% of online African-Americans, and 35% of online Hispanics downloading music files, compared to 28% of online whites.

- Consistent with our 2001 findings, young adults continue to dominate downloading—more than half of all Internet users between the ages of 18 and 29 have ever downloaded music and almost 10% of those in that age group are online downloading music on any given day. At the same time, Americans between ages 30 and 49 are also downloading regularly, with more than a quarter (27%) of Internet users in that age cohort reporting that they have downloaded music to their computers. Americans over the age of 50 are far less likely to download music, with 12% of those over age 50 reporting the activity.

- In a related finding, students are also more likely to be music downloaders than non-students. Fifty-six percent of full-time students and 40% of part-time students report downloading music files to their computer. Only a quarter of non-students report downloading files.

- An Internet user’s household income and education level are associated with downloading behavior. Internet users living in households that earn less income are more likely to download music. Thirty-eight percent of those earning less than $30,000 annually download music files, as opposed to 26% of Internet users earning more than $75,000 a year. Educational attainment shows a similar pattern, with 23% of online college grads downloading music files compared to 34% of Internet users with lower levels of education.

- Broadband users and frequent users of the Internet are much more likely to have ever downloaded songs. Indeed, 41% of Internet users with a broadband connection at home have ever downloaded music versus a quarter of dial-up users.

- Frequency of Internet use has a less pronounced effect on downloading behavior with 32% of those who log on daily having downloaded versus 27% of those who log on several times a week.

Downloaders are Copyright Care-free

Pew Internet findings show that the majority of those who download music are not concerned about the copyright status of those music files. However, some groups express more concern than others.

- Younger Americans are less likely to be concerned about copyright than any other age cohort. Seventy-two percent of online Americans aged 18 to 29 say they do not care whether the music they download onto their computers is copyrighted or not, compared to 61% of Internet users aged 30 to 49, the group that is the next most likely to download after young adults.

- Student status is also negatively associated with concern about copyright rules. Full-time students overwhelmingly express a lack of concern over the copyrights of the files they download—4 out of 5 say they are unconcerned. Part-time students and non-students are less likely to say that they are not concerned than full-time students—though it is still a majority of these groups (64% for part-timers and 63% for non-students) that are not worried about copyright on the songs they download.

- College graduates, however, are the group most likely to express concern about the copyrights on the music files they download from the Internet, with close to 40% expressing concern compared to a mere 22% of high school grads. Still, more than half of college grads are unconcerned about copyright, with 56% saying they do not care about the copyright on the songs they download.

- Parental status is also associated with people’s level of concern over the copyright of the music they are downloading. Parents are more likely than non-parents to say that copyright is a concern for them, though it is still only about a third of parents, and a quarter of non-parents who say that. Fifty-eight percent of parents and three quarters of non-parents say that copyright doesn’t matter to them. But even with parents’ increased concern over the legal status of the files they download, they aren’t any less likely to be downloaders than non-parents.

- Home broadband users are just as likely as dial-up users to say they are not concerned about the copyright status of the files they download.

The differences between men and women, blacks, whites and Hispanics and between income groups are not statistically significant, when it comes to copyright concerns.

Who is sharing files online?

File-sharers make up a somewhat different demographic slice of Internet users than downloaders, though 42% of downloaders share files.2 File-sharers are 21% of the Internet user population – or about 26 million people. File-sharers are equally as likely to be men or women, and equally as likely to be white, black or Hispanic. Not surprisingly, they are more likely to be younger, with 31% of the youngest adults aged 18 to 29 sharing files. The percentage of file-sharers among Internet users drops steadily with age, with 18% of those 30 to 49 sharing files on down to 15% of those Internet users 50 and older.

- Students are more likely to share files than non-students. More than a third (35%) of full-time students and 28% of part-time students share files, while 18% of non-students report the same behavior.

- Income level and education level show almost no correlation with file-sharing behavior. College grads are slightly less likely than high school grads (17% vs 22%) to share files online, but otherwise all Internet users are equally likely to be file-sharing, regardless of education. Income is similar, with no statistically significant difference among the income groups’ likelihood of file-sharing.

- Broadband users are much more likely to share files online than dial-up users—30% of Internet users with a broadband connection at home share files compared 19% of dial-up users. And in a slight departure from earlier findings on new users and enthusiasm for downloading, it is the most experienced Internet users who are more likely to share files. Only 13% of those online a year or less share files, while 23% of those with more than 4 years of experience online report sharing files.

File-sharers and copyright

As with those who download, those who take the next step and share files are also unlikely to express concern about the copyright of the files they share with others over the Internet.

Young adults are the least likely to express concern about the copyrights of the files they share with others, with 82% of file-sharers aged 18-29 saying they don’t care much about the copyright status of the files they share. Those aged 30 to 64 are more likely to express concern about copyrights, with about 2 in 5 file-sharers in those age groups saying as much. Nevertheless, in each age group, a plurality if not an out right majority of each group say that they are unconcerned about the copyright of the files they share online.

Students, both full-time and part-time, who share files, say they are not concerned about the copyright status of the files they share with others online. Eighty percent of full-time students and almost three-quarters of part-time students say they do not care whether the files they share are copyrighted or not. Fifty-nine percent of non-students say the same.

As with downloaders, college grads are the most likely to express concern over copyright amongst file-sharers. Those with lower levels of education are much more likely to express very little concern, and even amongst college grads, a majority (56%) say they don’t care much about copyright.

Also similar to downloaders, parents who share files are more likely to express concern than non-parents over the copyright of the files they make available. Thirty-seven percent of parents who share files say they care about copyright, versus a quarter of non-parents. Still, the majority, 57% and 71% of file-sharing parents and non-parents respectively say they do not care about copyright.

Those who share files and live in households with less than $30,000 in income are the most likely income group to say they do not care about copyright–with close to 80% saying they do not care about the status of the files they share. As incomes rise, concern over copyright rises, though even in the highest income groups (those earning $75,000 or more a year) 61% of Internet users who share files say they do not care about the copyright on those files.

There are no significant differences in copyright beliefs among file-sharers when it comes to their level of online experience, their frequency of use of the Internet, or whether they have a high-speed connection or not.

Methodology

This report is based on the findings of a daily tracking survey on Americans’ use of the Internet. The results in this report are based on data from telephone interviews conducted by Princeton Survey Research Associates between March 12-19 and April 29-May 20, 2003, among a sample of 2,515 adults, 18 and older. For results based on the total sample, one can say with 95% confidence that the error attributable to sampling and other random effects is plus or minus 3 percentage points. For results based Internet users (n=1,555), the margin of sampling error is plus or minus 3 percentage points. In addition to sampling error, question wording and practical difficulties in conducting telephone surveys may introduce some error or bias into the findings of opinion polls. The final response rate for this survey is 32.7 percent

The sample for this survey is a random digit sample of telephone numbers selected from telephone exchanges in the continental United States. The random digit aspect of the sample is used to avoid listing bias and provides representation of both listed and unlisted numbers (including not-yet-listed numbers). The design of the sample achieves this representation by random generation of the last two digits of telephone numbers selected on the basis of their area code, telephone exchange, and bank number.

Non-response in telephone interviews produces some known biases in survey-derived estimates because participation tends to vary for different subgroups of the population, and these subgroups are likely to vary also on questions of substantive interest. In order to compensate for these known biases, the sample data are weighted in analysis. The weights are derived using an iterative technique that simultaneously balances the distribution of all weighting parameters.

The Pew Internet & American Life Project

The Pew Internet & American Life Project is a non-profit initiative, fully-funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts. The Project creates original research that explores the impact of the Internet on children, families, communities, health care, schools, the work place, and civic/political life. The Pew Internet & American Life Project aims to be an authoritative source for timely information on the Internet’s growth and societal impact, through impartial research. For more information, please visit our website: https://legacy.pewresearch.org/internet/