Introduction

The Pew Internet & American Life Project, in a series of reports starting in May 2000, has found that email and the Internet foster social connectedness. Our first report, “Tracking Life Online,” found that Internet users perceive email as a valuable way to stay in touch with family and friends, with many people—especially women—reporting that email helps them feel more connected to their families and friends. Other Pew Internet Project reports underscore how the Internet has been integrated into people’s social lives in positive ways. Online communities are very popular and many participants report that cyber communities result in meaningful social contacts. Senior citizens embrace email as a way to keep up with children and grandchildren, and teenagers are among the most ardent Internet surfers. Teens “hang out” online in ways their parents did on the telephone or at the burger shop.

In this report, the Pew Internet & American Life Project traces the same Internet users from one year to the next. In March 2000, we interviewed 3,533 Americans, inquiring if they used the Internet and if so, what they do when they surf the Web and use email to stay in touch with family and friends. In March 2001, we reinterviewed 1,501 of the people we talked with in our March 2000 sample. Throughout this report, we compare the answers we got in 2001 to the answers we got from the same people in 2000. This provides a rich picture of how people’s Internet use changed over the course of a year.

Matching the 1,501 people from our March 2001 survey to the previous year, 57% said they were Internet users as of March 2001 – compared to the 46% of them who were Internet users in March 2000. As we did in March 2000, we asked people how the Internet has affected the way they keep up with family and friends. We probed whether and how often people go online for work-related tasks and we inquired into the kinds of activities people do online. Further, we pursued some new themes in March 2001, examining the impact of the Internet on people’s time-use and looking into people’s feelings about some of the Internet’s possible “hassle factors” such as unwanted spam emails.

Not only do we explore how people’s Internet use has changed in the aggregate between 2000 and 2001, we also examine how different kinds of users have changed their surfing patterns. A consistent finding throughout our reports is that the length of time a person has been using the Internet is a strong predictor of how often a person goes online and how much a user does on the Internet. The longer a person has been online, the more likely he or she is to have surfed for health care information, sent an instant message, or purchased a product over the Internet.

To explore the impact of users’ experience levels more carefully, we compare the Internet’s veterans or the “long wired,” who have been online for more than three years as of March 2000, to “mid-range” users who were online for two to three years in March 2000, and “newcomers” who were online for a year or less in March 2000. In analysis of these three categories below, when we refer to, say, newcomers in 2000 and newcomers in 2001, we refer to the same respondents and how their responses compared to what they told us in March 2000. We also analyze new users in 2001, that is, the people in our March 2000 sample who were not then online, but subsequently gained Internet access. These are the “brand newbies.”

Part 1: The Internet and work

As of January 2002 some 55 million American adults said they go online from work. For comparison’s sake, there were 43 million with work access in March 2000. That compares to the 103 million who currently have access at home. Many Americans, of course, have Internet access at both home and work. The basic breakdown is this: 49% of Internet users have access only at home; 8% of Internet users have access only at work; 39% have access at both home and work; and the remaining 4% have access in other places altogether such as at school or a local library.

When the Internet population was growing rapidly in the late 1990s and 2000 the growth in home access was the driver. The Internet was domesticated. However, our longitudinal study shows that the importance of the Internet in America’s workplaces is increasing. In comparison with the year 2000, people went online at work more frequently in 2001 with much of that extra Internet activity devoted to job-related research.

For those with access at work, daily Internet surfing is the norm. Some 55% of those with Internet access at work went online on a typical day in 2001, up from 50% in 2000. In many cases, they were logging on more frequently during the day at work than they did in the previous survey.

An increase in job-related research

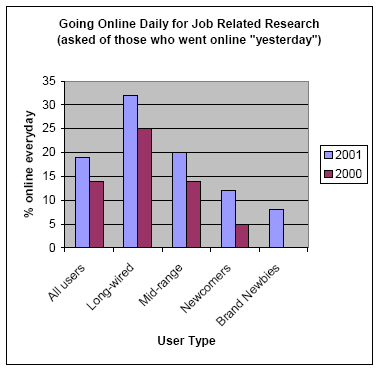

The increase in Internet use at the office is strongly tied to increases in those who do online research for job-related tasks. Of course, there is a great deal of email use at some offices, but the striking growth came in the frequency with which people were doing work-related research on the Web. In March 2001, 19% of all Internet users said they were doing work-related research on a typical day online, up from 14% on a typical day during the survey taken the previous year.

The emphasis on job-related research is characteristic of the Internet elite, with 2001’s “long wired” veterans four times as likely to do this as 2001’s new users (i.e., “brand newbies”).1 Online job-related research has become the norm for fully one-third of the Internet’s most veteran users, as 32% of this group says they turn to the Internet for work research on a typical day. However, growth in daily job-related research is most rapid among the less experienced. Since newcomers tend to have lower levels of educational attainment and lower incomes than the long-wired—and thus a different profile of occupations—the rapid growth suggests that the Internet as a tool at work is disseminating to a wide range of occupations.

Shifts in Internet usage

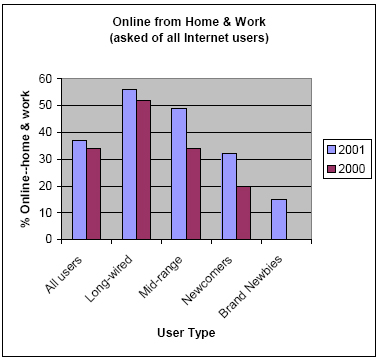

These changing patterns of workplace Internet use are part of shifts in the mix of people’s home versus workplace Internet use. Americans are spending a bit more time online at work and a bit less time online at home. Home-based Internet access remains the primary way people go online. However, on a typical day, there was a drop in the percentage of people who used the Internet only from home and an increase in the percentage who went online only from work. Three in five Internet users (59%) went online during a typical day in March 2000; a year later that number had dropped to 54%. Correspondingly, those who said they had gone online just from work increased slightly to 21% in 2001 from 18% a year earlier. Moreover, fewer Internet users are logging on at home several times a day, while more are logging on several times a day at the office.

The shifting patterns of where people go online are associated as well with the time of day they log on. We asked people what time of day they go online, and in March 2000 there was a fair number of evening and night owls. Fully half (49%) said they log on after 5 p.m. One year later, 40% of this group was going online during these hours. It may be that repeated Internet visits during the workday are taxing people’s stamina for surfing in the evening or that some leisure surfing is taking place during the workday.

The increasingly porous boundary between home and work

Growing numbers of Americans have access to the Internet at work and at home. That is especially true for Internet veterans: 56% of the “long wired” say they have access in both places, compared to only 32% of Internet novices who report access at work and at home.

The Internet’s growing role in the workplace has translated to changes in the amount of time people spend doing work – whether it is at the office or at home. One in seven Internet users say their use of the Internet has resulted in an increase in the amount of time they spend working at home and one in ten say the Internet increases the time they spend working at the office.

Although the magnitudes here are not great, the Internet veterans report greater impacts. Of those who have been online for more than three years, 21% report that the Internet has increased the amount of time they spend working at home, while 4% report it decreases the amount of time they spend working at home. These veterans also report large impacts when it comes to spending time at the office, but the effects cut both ways. Eleven percent of veterans say the Internet has increased the time they spend at the office; 11% say it decreases time at the office. This compares with 10% of Internet users who report an increase in time spent at the office and 6% who report a decrease.

Telecommuting’s payoff: Less time in traffic

The Internet’s longest wired Internet users are the most likely to say that the Internet has resulted in them spending more time working at home. For the 10 million Internet veterans who say they work more at home now, about 3 million are spending less time commuting in traffic.

The Internet’s impact on work life

For Internet users with access at work, four in nine (44%) say that the Internet improves their ability to do their job a lot. The Internet’s “long wired” users—those online for more than three years—report the greatest impact, with 55% saying the Internet has helped them at work a lot. By a large margin, those veterans who say the Internet has improved how they do their job are men—fully 60%. The effect is less pronounced for those new to the Internet, with 36% of newcomers saying the Internet has helped them a lot on the job.

Part 2: Connections to Family and Friends

Americans’ engagement with the Internet as a way to stay in touch with friends and family remains strong. In March 2000, 79% of Internet users said that they email members of their immediate and extended family, a number that grew to 84% a year later. Seventy-nine percent of all Internet users said they email friends in March 2000, essentially the same as the 80% who said they email friends in March 2001.

However, as some people gain experience online their perceptions of the Internet’s role in personal communication change. Fewer report that emailing is very useful for being in contact with family and friends and a notable number of email users cut back the frequency with which they email family and friends. At the same time, they show a substantial increase in the use of email for serious communication, such as sharing worries and seeking advice. All this is in the context of people continuing to value the Internet highly; 82% of veterans said that in 2001 compared with 68% who said it in 2000.

These seemingly paradoxical changes reflect a maturation process for Internet users. For many, the Internet until recently has been a “wow” technology, but with time it has receded somewhat into the background of their lives. For veteran users especially, the Internet has acquired a quotidian cast. This takes place in the context of more of people’s social and professional networks going online as Internet penetration grows. A wider range of friends and contacts online makes it more acceptable to handle important matters over the Internet, especially as online experience breeds trust of the technology. The expanding population of cyberspace and users’ greater comfort with the Internet changes the norms of appropriate and expected online communication. Users’ initial wonderment over the technology shifts to a richer appreciation of what it can do for them, whether that means sending a credit card number or sharing an urgent worry.

Extensive contacts, less fervor

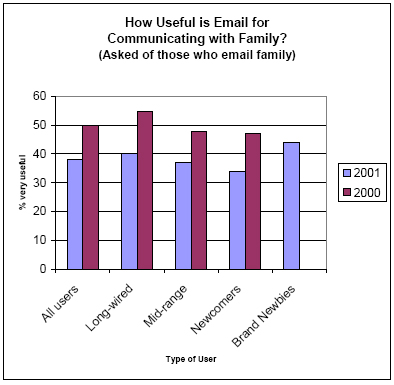

In March 2001, 79% of those who email family members reported that email is “very useful” or “somewhat useful” for keeping up with family members, down from 88% who said that in March 2000. The decrease is attributable to the falling share of people rating email as “very useful” for communicating with family members; 50% said that in March 2000, but that fell to 38% in March 2001. The drop is most pronounced for Internet’s “long-wired,” suggesting that the longer one has been online, the less likely one is to rate email as a “very useful” communications tool.

In fact, brand newbies in 2001 are most likely to see the Internet as a “very useful” way to communicate with family; 44% say this versus 40% for Internet veterans. If recent history is a guide, however, this effect may be short-lived for people who came online between March 2000 and March 2001. People who came online during the year prior to March 2000 (i.e., novices in 2000) reported a decline in support for the idea that the Internet is “very useful” for communicating with family; 47% felt this way in 2000 but a year later that number fell to 34%.

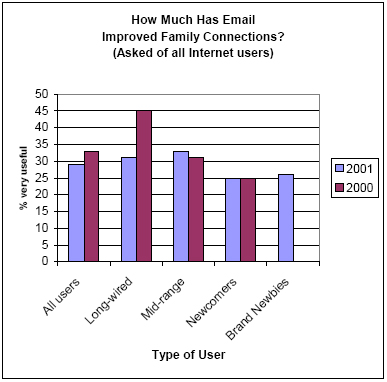

When asked whether the Internet has improved connections with family, 60% of March 2000 respondents said the Internet has improved their connection to family members “a lot” or “some,” a number that fell slightly to 56% in March 2001. One-third (33%) of the March 2000 sample said the Internet helped family connections “a lot” versus 29% who said that in March 2001. The drop is entirely a phenomenon of Internet veterans, nearly half (45%) of whom in March 2000 said the Internet helped improve connections “a lot,” but only one-third (31%) said so a year later.

Consistent with the finding that Internet users are less likely to email family members, we find that a year’s time means that people are less likely to say that they communicate more with family members now that they use email. In March 2000, 56% of those who email family members said that they communicate more with others in the family now that they have email. This number fell to 46% in 2001. At the same time, people are somewhat more likely in 2001 to say that email has improved family relationships. In March 2000, 35% of Internet users said the Internet has improved family relationships; this number increased to 39% in March 2001. Again, this suggests that though frequency of contact may decline, the Internet positive impact on family relationships does not decline.

Emailing friends

The story is similar, although the less pronounced, when people are asked about using email to communicate with friends. In March 2000, 92% of those who email friends said email was useful to stay in touch with friends, with 55% saying it was “very useful.” In March 2001, 90% of people who email friends said email was a useful way to connect with friends; 52% said it was “very useful.” Long-wired Internet users are largely responsible for this decrease, with this class of Internet user being the only one in which a year’s time led to a decline in support for the idea that the Internet is a “very useful” way to communicate with friends.

For connections to friends, 69% of March 2000’s Internet users said the Internet improved connections to friends “a lot” or “somewhat” and 65% said this in March 2001. The share of people saying the Internet improved connections to friends changed very little, going from 37% in 2000 to 35% in 2001. Within categories of users, again it was the veterans who recorded a notable decline in enthusiasm for this proposition. Similarly, people were somewhat less likely to say email has increased the amount of communication with friends, with 61% of those who email friends saying in March 2000 that email means they communicate with friends more often, compared to 54% saying that a year later.

Other evidence of the lower Internet buzz

Other evidence from our survey points to a consistent trend of people heralding the Internet less as their online experience increases. Fully 76% of Internet users in 2000 said that the Internet improves their ability to learn new things, with 50% saying it helps “a lot.” That number fell a bit to 73%, but a year later only 39% said it helps “a lot” with an increase in people saying it helps “some.” As with family emailing, veterans showed the sharpest drop in saying the Internet helps a lot in learning new things, with novices maintaining a relatively high level of enthusiasm.

Daily emailing declines, but seeking advice surges

People’s emailing habits have changed in a year’s time, with the daily email to family and friends becoming less frequent. Accompanying this decline, however, has been a sharp increase in the use of email for important communications. Many more people in 2001 report that they use email to get advice or share worries with those close to them.

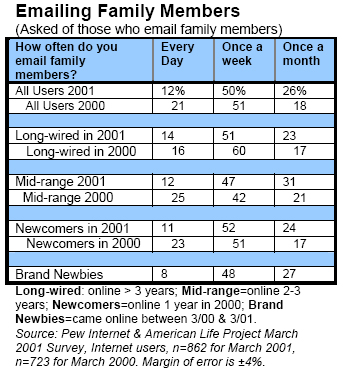

Some 12% of people who have ever emailed family members sent email to a key family member every day in 2001, down from 21% in 2000. Newcomers to the Internet in 2000 had the starkest declines, suggesting a novelty effect wearing off. Similarly, about 13% of Internet users emailed a key friend on a daily basis in 2001, down from 17% in 2000. The weekly email is the staple for most Internet users, as about 50% of email users said they send electronic messages to family and friends once a week.

A closer look at the patterns of family emailing show a shift from the daily email to the monthly e-note; 26% said they emailed a family member once a month in March 2001 up from 18% the year before. Half reported emailing a family member once a week in March 2000 and March 2001. The same patterns were evident for those who email friends.

Looking at user categories, the relatively new users report the sharpest declines in daily emailing to family members, with most of that emailing apparently shifting to monthly missives. Even with these changes, throughout all experience levels, about half of Internet users seem content emailing a friend or family member about once a week.

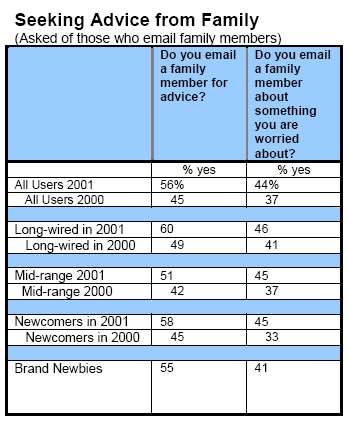

Notwithstanding the decline in emailing, Internet users have deepened their email contacts with others in several ways. An extra year of online experience seems to make Internet users more comfortable with using email to pursue difficult issues with family and friends. In March 2000, 37% of Internet users who email family members said they sometimes raise issues that they worry about or are upset about in emails to family. That number increased to 44% in 2001. In absolute numbers, 25 million Americans had emailed family members about worries in March 2000, but this number jumped by 60% to 40 million in March 2001.

The pattern of more serious email is more pronounced when asked about seeking advice from family members. Forty-five percent of March 2000 respondents who email family members say they do so to get advice; one year later, 56% said they had emailed a family member seeking advice. In absolute numbers, 30 million Americans had emailed family members about worries in March 2000, but this number jumped by 70% to 51 million in March 2001.

Internet users who came online in the last year and March 2000’s newcomers seem particularly ardent about using the Internet to seek advice or raising worries with friends and family members. Online experience usually means a user is more likely use the Internet for any activity. This general pattern does not hold for the increases in emails seeking advice or about worries. A better explanation is that a network effect is at work. As more and more people go online, there is increased incentive to use email for all kinds of communications. Experience doesn’t explain the growth in the seriousness of email as much as the fact that people rely on email to perform all kinds of important communications, regardless of their experience level online.

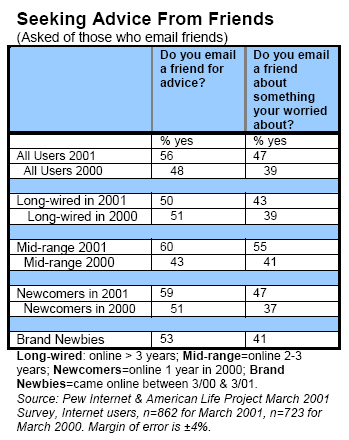

For friends, the story is much the same. By March 2001, 41 million Internet users had emailed friends to share worries, up from 26 million a year earlier. Advice-seeking among friends has gone up as well, from 32 million in March 2000 to 49 million in March 2001. The largest increase in this activity is from middle users, who are the most likely in any user class to have emailed friends for advice or to share worries.

Women are still the fervent family emailers

In our May 2000 “Tracking Life Online” report, we found that women are the Internet’s most enthusiastic emailers, and this finding holds up in looking at changes over the March 2000 to March 2001 timeframe. Women are much more likely to be daily emailers than men in 2001 (by a 19% to 5% margin). Similarly, women are more likely than men to find email a very useful way to keep in touch with family members. Four in nine (45%) women who email family members said this in 2001 compared with 30% of men. In March 2000, the numbers were 58% for women and 41% for men. Over time, men and women both report a decline in their feeling that email helps them connect with family and friends.

The “clicking cousins” effect and extended networks

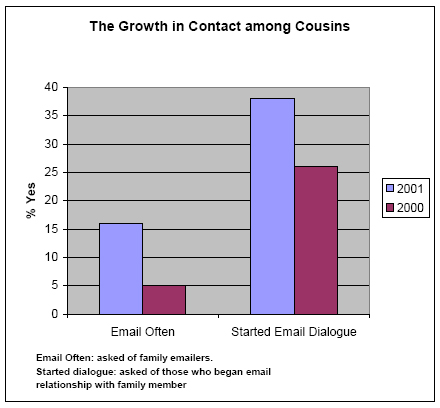

An extra year of online experience seems to bring people more in contact with their cousins—an online “clicking cousins” effect. As already noted, 84% of the March 2001 sample say they have emailed family members, up from 79% in March 2000. This suggests that many of our March 2000 respondents who came online in the past year email family members. This increase is due in part to growth in emailing to extended family members.

When Internet users who email family members were asked in March 2000 about family members they email frequently, 5% identified a cousin as that person, a number that rose to 16% in March 2001. The “clicking cousins” effect persists when people were asked if they had started communicating via the Internet with a family member they had not been in close touch with. For those who answered “yes” to this question (29% in 2001 and 32% in 2000), nearly 4 in 10 (38%) of 2001 respondents identified a cousin as the family member with whom they began an e-dialogue. This is an increase from 26% who identified a cousin on March 2000.

The “clicking cousins” phenomenon indicates that online experience helps extend family networks. The quick “hello” email seems to be a great way to renew family ties that have withered. Indeed, about one quarter (27%) of Internet users in 2001 said they had used the Internet to track down a friend or family member with whom they had lost touch. Twenty-nine percent of 2001 email users say they now use email to communicate regularly with a family member they had not kept up with before. The renewal of family ties via email persists over time, as evidenced by the clicking cousin’s effect, which is giving electronic life to the extended family.

Part 3: Transactions and other activities online

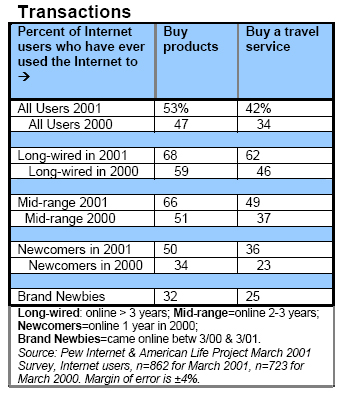

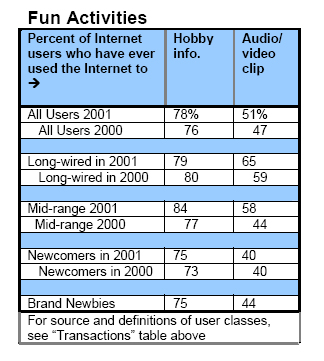

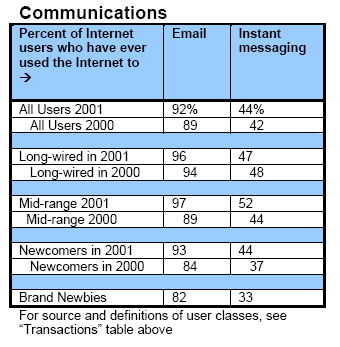

In the 13 months of tracking polling we have done, we have asked Internet users about 52 different kinds of activities online, including their use of email and their use of the Web to do such things as get news, download music, purchase stocks, get religious information, make travel plans, research medical information, and pursue their hobbies. In the longitudinal study, we probed 24 kinds of activities in each year and observed an expanded range of things people do online. The average Internet user in March 2001 had tried at one time or another 14 of these 24 activities, an increase from 11 in March 2000. An appendix to the report lists all 24 activities and compares for 2000 and 2001 the numbers of Americans and percentage of Internet users who have done online activities. Email remains the most popular activity for Internet users. In the March 2001 survey 92% of respondents told us they were email users. (In the January 2002 tracking survey 95% of online Americans said they had sent or received email.) In March 2001, the number two activity was going online to look for information about a hobby: 78% of Internet users had done that.

The sections in this part of the report and the tables in those sections show how often all Internet users, and different classes of users, go online for activities that are broadly categorized as communications, information utilities, fun online diversions, and transactions. Comparing what Internet users did in March 2001 to a year earlier, people are generally a little bit busier when it comes to online activities, with two to four point increases for activities such as emailing, instant messaging, playing a game, getting health care information, and others. Some categories of activities are marked by high growth, some by low growth, and within categories there is often variation in growth rates depending on users’ levels of experience.

The pattern of growth, especially in transactions and seeking information online, is indicative of an increasingly utilitarian Internet. People go online to save time by conducting a transaction or to satisfy specific information needs, such as health care queries or accessing a government Web site.

Money matters: High growth activities with novices leading the way

Sizable jumps have occurred in transactions, with six- and eight-point increases for buying things online and buying travel services, respectively, and a six-point increase for online auctions. All classes of users have increased the frequency of transactions, but people who were new to the Internet in March 2000 showed the most dramatic increases. For both the purchase of any kind of product online and for travel services, newcomers in 2000 were about 50% more likely to have done these things a year later. Prior work by the Pew Internet Project has found that new Internet users are initially reluctant to conduct transactions online, but that once they take that step, they quickly become engaged with doing transactions over the Internet. These findings buttress this analysis, as familiarity with the online world fosters comfort with transactions for newcomers.

Online amusements: Low growth—for novices especially

For fun Internet activities, users report little or no growth in having gone online for hobbies, game playing, or just to seek out fun diversions. Even for newcomers, growth is tepid, perhaps because they start out at a level of activity that is close to or on par with their more experienced counterparts. The notable patterns of growth occur for listening to or downloading music and getting an audio or video clip on the Internet. Although overall growth for these categories is not great, a striking amount of it comes from “mid-range” users—people who were online about two to three years in 2000. As these users gain experience they become the group most likely to download music from the Net and are catching up quickly to veterans when it comes to accessing audio and video clips online.

Demographics may have a lot to do with the strong growth exhibited by “mid-rangers” relative to veterans. The Internet’s veterans are 60% male, while 53% of “mid-rangers” are female. Age is another difference between the two groups. “Mid-rangers” are generally younger than veterans, with 22% of veterans falling in the 18 to 29 cohort, compared to 29% of middle users being between 18 and 29. The relative youth of “mid-rangers” accounts for much of the greater interest in music and video online, and women account for slightly more of the growth in these two categories than men.

Information Seeking: Low growth—except for veterans

The number of those seeking information of various kinds online has shown modest growth between March 2000 and March 2001. Only veterans show a marked growth in all of the activities we classify as information-seeking activities.

The pattern is mixed, depending on the specific information-seeking activity. For instance, many newcomers find surfing for health care a very attractive thing—it is their most popular information-seeking activity. But the newcomers who don’t want to get medical information when they first go online are unlikely to use the Internet to get such information even as they gain a year’s experience with using the Internet. It might be that they are concerned about the trustworthiness of such information or their personal privacy. It might also be true that over the course of a year, most of these newcomers had no particular reason to want to get health or medical information. Whatever the case, it is not something that experience seems to have affected very much.

Similarly, there is some growth in visits to government Web sites. However, much of the growth in this activity has come from newcomers. Although it is hard to pin down the reason for such rapid growth among novices, the April tax filing deadline could have drawn people to government sites for tax forms and information. And the election controversy at the end of 2000 might have stimulated traffic to government sites.

Reaching out: Instant messaging takes off for novices

Email remains the dominant single activity on the Internet, with 92% of the respondents in March 2001 telling us they had sent or received email. Although the overall growth between 2000 and 2001 is small, it is concentrated among newcomers and mid-range users. The growth among middle users is probably traceable to the majority of women in this group; as our March 2000 report found, women tend to email more often than men. Instant messaging is, on average, not a quickly growing activity, but what growth is evident is found in novice and middle users.

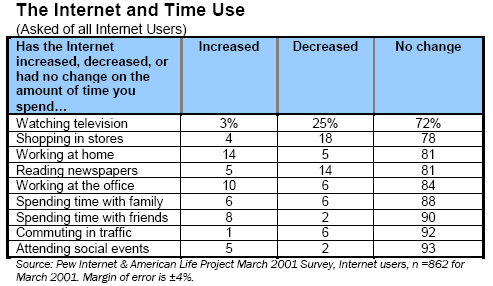

Part 4: The Internet, time use, and things that annoy

As people continue to use the Internet to maintain connections with family and friends, and as the Internet takes on a more prominent role in the workplace, it is sensible to ask two questions about time use. One is whether the passage of time is associated with people spending more or less time online. The other has to do with the Internet’s overall impact on how people spend their time. Do people say that the Internet changes the amount of time they spend with family and friends? What do people report about the Internet’s impact on the amount of time they spend at work, shopping, commuting, or watching TV?

Seven-minute shorter sessions

With respect to the amount of time people spend on the Internet, we asked people who said they went online on the day before we contacted them to estimate about how much time they spent emailing or surfing the Web. In March 2000, the average Internet user spent about 90 minutes online during a typical session “yesterday.” When asked the same question in 2001, the same set of users reported a modest decrease of about 7 minutes in the amount of time they spent online during that typical session.

Thus, Internet use is evolving in several ways: People spend less time online, but they have sampled more activities. They are less likely to herald the Internet’s connective effects, but they use it for more serious purposes. This all suggests that they learn what they value online and how to go about finding it. Their online habits become more directed and efficient, allowing them to get what they need in shorter order than before.

What Internet use displaces

The following table gives a flavor of where people are finding the roughly 83 minutes or so they spend online during a typical session. By far the greatest impact comes in television viewing. Fully one-quarter of Internet users said that surfing the Internet has led to a decrease in TV time. For the Internet’s most experienced users (those who have been online for three or more years), this number rises to about one-third, as 31% of those users say the Internet has decreased the amount of time they watch TV. Traditional media also takes a hit when looking at time spent reading newspapers. One in seven (14%) Internet users say the Internet has decreased the time they spend reading newspapers. For the Internet’s veterans, this number rises to 21%, although these users are also the most likely to go online to get news.

Shopping in stores is another thing people report doing less as they spend more time online. Nearly one in five (18%) of Internet users say that the Net has resulted in them spending less time shopping in stores, with only a few saying that the Internet has drawn them to shops and malls. Again, the Internet elite leads the way in using the Internet to shop; fully 28% of the Internet’s long-time users report that the Internet has led to a decrease in the time they spend in stores. Online shoppers very likely use the Net to stay out of stores; 29% of people who have shopped online say they spend less time in stores due to the Internet. Of the Internet users who came online between March 2000 and 2001, only 10% said the Internet contributed to a decrease in the time they spend in stores. Other classes of users (i.e., those online about a year, or those online from two to three years) said about 11% of the time that the Internet decreased the time they spent in stores shopping.

Hassle factors – spam and email promoting porn

Even as Internet use has taken on greater importance in the workplace, and as online Americans continue to use the Internet to maintain ties with family and friends, Internet users express growing irritation with their ability to manage the nature and volume of some kinds of email. In March 2000, one-third (33%) of all Internet users said that “spam” or unwanted email messages were a problem for them. One year later, that number rose to 44%. Fully half of the Internet’s most veteran users say that the volume of spam was a problem for them. Those who are new to the Internet are much less likely to cite “spam” as a problem, as only 26% of Internet novices say that such emails are problems for them.

We asked people to classify the nature of the unwanted messages they receive and, overwhelmingly, Internet users cite sales solicitations. Fully 78% of users in March 2001 said sales solicitations are the type of spam they receive, up from 68% who said this in March 2000.

We also probed into a particular type of spam that is often cited as an annoyance to Internet users—messages with adult content or from adult Web sites. More than half—56%—of U.S. email users have at one time or another received an email from an adult Web site or that contained adult content. Twenty percent report that this occurs often, with Internet veterans twice as likely as novices to receive such messages (24% for veterans versus 12% for novices). The greater incidence for veterans is likely to be nothing more than a reflection of the number of years they have been online. Their more extensive surfing habits increases the chances that traces of information identifying their email addresses have been picked up by these sites.