Families and the Internet

In addition to altering how teens interact with their friends, the Internet is introducing new dynamics into family life. In their overall judgment, parents think that the Internet’s role in their children’s lives beneficial. More than half of parents of online youth (55%) believe the Net is generally a good thing for their children and only 6% believe it is bad for their children. Some 38% do not think it has had an effect on their child one way or the other.

In many families, a child has mastered a technology before the parents. Teens often are the instigators of the family’s first foray onto the Internet and end up teaching other family members how to use it. These new developments reverse the tradition of parents as teachers and children as learners and can play a beneficial role in family life as the teens gain in self-respect and show their competence to their parents. It is easy to see how this could enhance parent-child relationships. However, this new arrangement is taking place during the tumultuous teen years, when children more aggressively test limits and move beyond the parameters of their family. So, this role reversal can exacerbate family conflicts and add new topics over which to argue.

Parents also have concerns about the amount of time that their children spend online and about the people and material they will encounter in cyberspace. These worries prompt many parents to impose rules on Internet use, to monitor their children’s online activities, and to install software to prevent their children from accessing objectionable material.

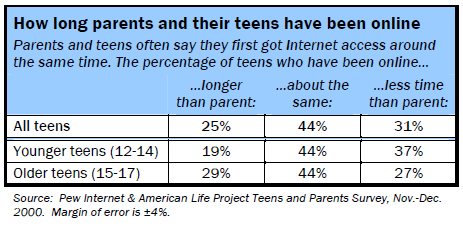

Many families first connect to the Internet in the same time period. The most noticeable variation in sequencing of who first got Internet access occurs between younger and older teens.

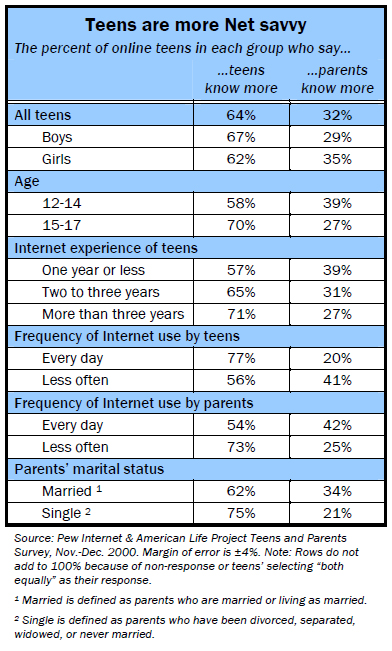

Teens know the Net better than their parents

Most youth and parents agree that the children know more about the Internet than their parents. Nearly two-thirds of online teens (64%) believe that and a slightly greater percentage of parents (66%) agree. More online boys say that than girls and more older teens say that than younger teens. This view is especially prevalent among online teens from families with modest incomes and those who live in single-parent homes.

The more recently a parent has gone online, the more likely it is that the teenager believes he knows more about the Internet than his parents. Fully 70% of online teens whose parents went online in the last year say they know more, compared to 53% of online teens whose parents have been online for more than three years.

When it comes to parents, more online fathers than mothers say they know more about the Internet than their children; more college-educated parents say this than those without college degrees; and parents with a substantial amount of Internet experience are more likely to say they know more about the Internet than online parents who have just gotten access to the Internet.

How parents and youth learn about the Net

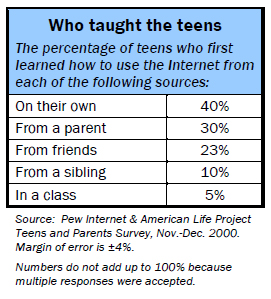

Forty percent of online teens report teaching themselves how to use email and the Internet. And they are not just teaching themselves – often, they are the ones who learn how to use the Internet and then teach their families. “At the time this was all beginning, no one else in our household beside myself knew how to do anything on any computer,” reported a 17-year-old boy in the Greenfield Online group. “I had to write out instructions and tape them to sides of the monitor so that they’d know how to turn the computer on.” Another 30% of teens report learning it from their parents. Only 5% learned from a class. “I learned the basics of the Internet (browsing, searching, E-Mail) at a summer course at school, but I taught myself the rest (downloading programs, instant messaging, etc.),” said a girl, 15, in the Greenfield Online group.

Teens with the most knowledgeable parents (those who have been online longer than 3 years) were the most likely to be taught by their parents (43%). Those teens whose parents don’t go online mainly learned how to use the Internet from friends (33%) or by teaching themselves (39%). Girls are more likely to have learned from their parents than boys, and boys are more likely to report being self-taught. A shift back to more traditional parent-child roles might be occurring, though, because a plurality of younger teens, regardless of gender, reported learning to use the Internet from their parents. Among 12- to 14-year-olds, 41% were taught by parents, compared to 22% of older teens. More than half (51%) of teens 15 to 17 report learning to use the Internet on their own.

Some of the differences between how teens of different ages learned to use the Internet can be explained by the pattern of Internet adoption in the U.S. About three years ago, Americans, both adults and teens started going online in droves. Often older teens with more interest and leisure time mastered the new technology and taught it to friends and family. Youth who are aged 12 through 14 are more likely to have parents who went online before them, and more likely than other teens to report that their parents taught them how use the Internet. Many of these parents had Internet access at work or school, and thus were already familiar enough with the technology, even if they did not have it at home, to teach their children how to use it.

Teens say they go online for the first time for a variety of reasons. “My dad got the Internet at home because he wanted us all to ‘get with the times’ so to speak,” said one 16-year-old boy in the Greenfield Online group. Other parents decide to go online because they felt it was vital to the education of the children in the family. “I got it because I needed it for school and because it keeps me out of trouble,” wrote a 17-year-old girl. And some families got the Internet because the children really wanted it. “My dad decided to get the net because I begged and begged him for it,” said a 14-year-old girl also in the Greenfield Online group discussion.

Conflict over access to the Net

The vast majority of the youth who have access to the Internet gain their access through their homes. Fully 90% of the online teens in our sample say they go online from home. And 94% of those with home access say they must share a computer with siblings or other family members. This sometimes causes family conflict. Indeed, 40% of the parents of online teens have had an argument with their children about using the Internet.

The amount of time teens spend online is a big factor. “The only thing we seem to disagree about is how much time I want online and how much I get,” noted one boy, 17, in the Greenfield discussion group.

A 17-year-old girl in the Greenfield group described the struggle over access to the Internet this way: “I usually demand to get on the computer, and my brother yells at me that he’s gonna take even longer. Then I tell my mom that I really need to go on and she makes me ask my brother nicely. He usually takes a long time though just to spite me.” Others in the teen groups told of how families construct elaborate schedules of time for Internet use.

Other times, there is conflict over the nature of the online world. One 17-year-old girl described the evolution her relationship with her parents about the Internet this way in the Greenfield group: “At first, there were disagreements on where I could go, or couldn’t go. But as time went on, they [her parents] realized that the Internet was not a bad thing, but a good thing that was a great learning tool. I dealt with these problems by talking to them, and showing them where I went. They would frequently watch from behind and monitor where I was going. When they realized I wasn’t trying to defy them, they eased up and gave me freedom.”

The Internet’s impact on family relationships

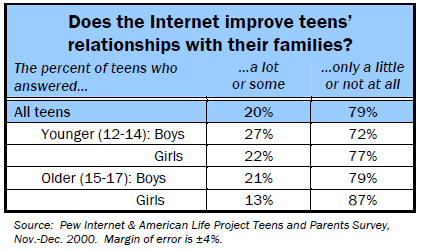

The conflicts surrounding time use as well as content accessed on Internet-connected computers may be part of the reason why teens do not think the Internet is helping their relationships with their families. In fact, most teens (61%) do not think that the Internet helps their relationships with their families at all. Almost two-thirds of online teens (64%) express a generalized concern that young people’s use of the Internet takes away time they would spend with their families. Some 69% of girls say that and 59% of boys agree.

When asked whether the Internet has improved how they spend time with their children, 79% of parents say it has not helped at all or has only helped a “little bit.” The frequency with which both parent and child go online is closely associated with the level of improvement they report. Parents who go online every day and parents of children who go online daily both report a greater sense of improvement in how they spend time with their children.

Parents and their children are evenly split on the question of whether the Net improves their children’s relationships with their friends. Almost half of each generation (48%) believe Internet use is tied to improved friendships. “When I did not have any classes with my best friend the other year, we emailed each other every day and told each other the details of our day,” said a 17-year-old girl in the Greenfield Online group discussion. “That brought us much closer together. That was when our friendship became stronger.” The teens who are the most active Internet users are the most likely to express these positive feelings. In addition, fathers are more likely to report positive feelings than mothers, and the parents who use the Internet the most are the most enthusiastic about the beneficial impact of the Internet on their children’s relationship with friends.

The Internet’s impact on family activities

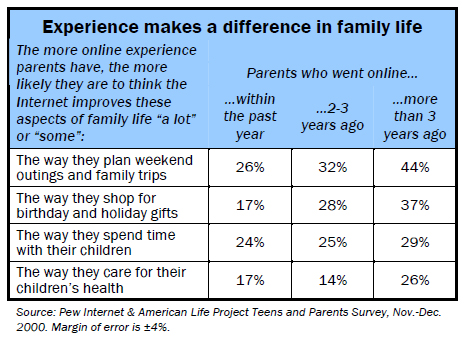

In most online homes, parents do not think the Internet has affected interfamily relations much. Still, some believe that the Internet has contributed at least somewhat to enjoyable family activities. More than a third (34%) of parents say the Internet has helped them plan weekend outings; 27% say it has helped them shop for birthday and holiday gifts for family members; 26% say it has improved the way they spend time with their children; and 19% say it has improved the way they care for their children’s health. There are sharp differences in the views held by online veterans compared to newbies on all these issues. The longer a parent has been online, the more likely it is for that parent to have quite positive things to say about the impact of the Internet on family life.

Planning by email

A significant bloc of parents is using email to do some of the logistics planning in their children’s lives that used to be conducted by phone. More than a quarter of parents with Internet access (28%) use email to communicate with their children’s teachers; and a fifth of online parents (20%) use email to stay in contact with the parents of their children’s friends. Parents in high-income households and parents with high levels of education are more likely to have used email to communicate with teachers than are other parents. Parents of younger children are a bit more likely to be in touch by email with the parents of their child’s friends. And almost a third (32%) of parents who are veteran users of the Net stay in contact with other parents by email – compared to 17% of parents who’ve been online for a year or less.

Concerns and Fears

Parents agree that for the most part the Internet is a good thing or at least has a neutral impact on their own children. Still, parents have many concerns about the Internet and struggle to protect their children from the worst elements online – dreadful people and ugly information – without keeping children from its benefits.

Parents of girls are more concerned than parents of boys that their children will be victimized online – that they will be stalked, harassed, and that they will susceptible to advertising. This clearly carries over to the Internet the concerns that girls’ parents have about all kinds experiences and threats.

Wired parents are generally much less worried about the impact of the Internet on their children than parents who do not have Internet access. Online parents tend to be more vigilant in monitoring what their children do on the Internet, but also seem more confident that their children can avoid trouble. Parents with considerable online experience express even less concern than those who have recently come online.

For their part, online teens as a group are generally much less concerned than parents about online content and do not feel as strongly that they need to be protected.

Worrying about strangers

Fifty-seven percent of parents of online teens worry that their children will be contacted by strangers via the Net – 25% of parents worry “a lot.” Parents of girls and of younger children worry more than other parents. We noted above that 50% of online teens who use instant messaging, chats or email report sending email or writing instant messages with someone they have not met before. “I rarely talk to anyone I don’t know on the Internet,” said one girl, 17, from the Greenfield Online group discussion. “Sometimes when I have, though, it will get creepy when they start asking for information about you, or for pictures.” But for the most part, these exchanges do not give these teens pause. Fully 52% teens of all online teens say they do not worry at all about being contacted by strangers online. Only 23% worry some or a lot.

Still, more than a quarter of all online girls (27%) worry that someone they do not know might find out who they are or try to contact them because they see them online. In comparison, only 18% of all online boys feel the same way. More younger children worry about this than older children and younger girls are the most concerned. One 15-year-old girl in the Greenfield online group spoke of her brush with the darker side of online strangers: “I’ve been…harassed. Cyber racists run rampant nowadays. One had a screen name that said “I Persecute Jews”, and IM-ed me saying “How are you Jewin today?” So I block the guy, and then I get another IM from the same stalker with another name “Black Lotus.” It’s amazing, I guess people do express themselves better online. It’s just that those deep feelings are often dark and offensive.”

Inappropriate content

Parents are also concerned about what their children might see or read online. Sixty-two percent of parents express a lot or some concern about what their children might seek out or stumble across on the Internet. More parents of younger children are worried about this problem than parents of older children—68% of parents of 12-to 14-year-olds expressed a lot or some concern; whereas 58% of parents of teens 15-17 said the same.

A bad influence?

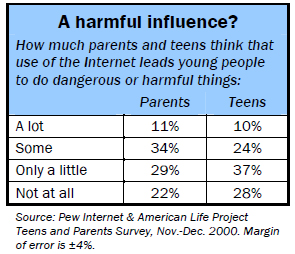

About half (45%) of parents are worried that the Internet leads some young people to do dangerous or harmful things. Yet only 11% report a lot of worry, and 34% reporting some. Parents who do not use the Internet themselves tend to be more concerned than parents with more online experience.

Teens themselves register even less concern than their parents. The largest group of teens (37%) answered that they believed that the Internet causes other young people to do dangerous or harmful things “only a little” and another 28% said “not at all.”

The Internet as a distraction

Parents are quite concerned that Internet keeps teens generally from doing more important things. Sixty-seven percent of all parents expressed some or a lot of worry about the distracting qualities of the Net. Parents of youth who go online on a daily basis are the most concerned parents, with 72% saying that they worried the Internet was keeping their children from doing more important things.

Online youth do not express many concerns about the impact of their own use of the Internet, but they fear use of the Internet keeps others from doing more worthwhile things. Almost two thirds of online teens (62%) think that the Internet does keep young people from doing more important things. Older girls are the most likely to view the Internet as a distraction, with 68% saying it keeps teens from doing more important things.

Still, many teens acknowledge that the Internet does keep them from doing other things that they ought to be doing. “I’ve been doing my homework later than usual because I just seem to get carried away online and forget I have homework,” admitted one 17-year-old girl in the Greenfield discussion group.

Exploited by advertising

A bit more than half of all parents are concerned that companies will push advertising to their children. Fifty-eight percent of parents say that this concerns them some or a lot. Parents of girls 12 to 14 are the most concerned that advertisers will target their daughters online. Parents who are newer the Net express more concern than their veteran counterparts – 64% of parents who went online in the last year are worried about their children being exploited advertising, compared to 56% of those with more than a year of experience. For some online teens, concern about privacy is a serious issue. “I’m not concerned about malicious individuals obtaining my information, but about unethical companies,” said one 16-year-old boy in the Greenfield Online group discussion. “I don’t mind targeted banner ads, but I have grave objections to my personal information being sold, since it always results in more junk mail and e-mail.”

The Internet is worse than TV

Asked to compare their worries about Internet content compared to TV content, more parents said they worry about Internet content. Thirty-eight percent of all parents are most concerned about the Internet, 16% are most concerned about what their children view on television, and 29% of parents are equally concerned about TV and the Net. Seventeen percent of parents are not concerned about either medium.

How Parents Protect Their Children Online

Rules

Fully 61% of parents of online teens say they impose time limits on how long their children can stay online. But only 37% of the online teens in our sample say such limits are imposed on them. Young teens are more likely than older teens to say they have rules.

Here is how parents use of time limits on Internet use compares to other key household technologies: Close to half (47%) of teens with Internet access say they have limits on the amount of time they can talk on the phone; 40% have limits on how much television they can watch; and 35% have time limits on playing computer games.

Checking up

A substantial majority of parents (61%) say they monitor the sites their children view by checking up on the children after they have gone online. But less than a third (27%) of online teens believed that their parents follow up on their online behavior. Boys were much more likely than girls (34%, compared to 20%) to say that they thought their parents were following up. But parents report monitoring at roughly the same rate for their sons and daughters (62% for sons, 59% for daughters).

Surfing together

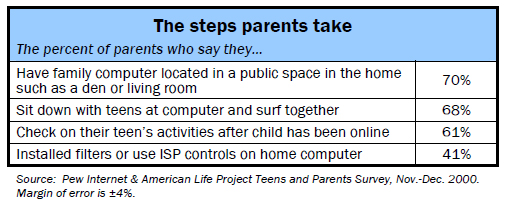

Another tool that parents use to control what their children see and do online is to actually sit down and surf along side their son or daughter. Close to seven in 10 parents (68%) report sitting down at the computer with their child. More mothers than fathers sit down at their computers with their children. Interestingly, 34% of parents who say that they “do not go online” say they do sit down and go online with their children.

Parents are more likely to sit down and go online with younger teens than older teens – 78% of parents of online 12- and 13-year-olds have ever gone online with them compared to 63% of parents of 14-to-17 year olds. Teens on the other hand say that a little less than half (48%) of them have ever sat down at the computer with their mother or father.

The computer out in the open

Most families seem to be listening to the advice of child advocates who urge them to put the computer in a public space in their homes such as a den or living room. Of youth who have access at home, 70% have their computer located in a public household space like a living room, study, den or family room. Twenty-seven percent have the computer located somewhere private, like a private bedroom. Sometimes the space is a little less definitely private or public. “My computer is located in the ‘office.’ This is where my dad does his work and my sister and I do our homework,” noted one 17-year-old girl in the Greenfield Online group discussion. “It is pretty private in the sense that there is a closeable door, and no one really goes in there unless they need to use the computer for something.”

Younger teens are more likely to use a computer in a public space than their older counterparts. Youth who go online every day are more likely to use a computer in a private space than youth who go online less often. Youth whose parents do not go online are also more likely to have their computer located somewhere private.

Filters

Technological filters have enjoyed a wave of news coverage recently with the passage of the Children’s Internet Protection Act on December 21, 2000. The bill mandates that all schools and libraries receiving federal funding must employ filters to prevent young people from accessing pornographic or indecent material, and is supposed to be implemented by July, 2002. The American Civil Liberties Union and the American Library Association have mounted an attack against the implementation of the bill. And in February, Consumer Reports concluded that filters generally fail to block out 20% of objectionable sites, and also block out educational sites with objectionable words or subjects.

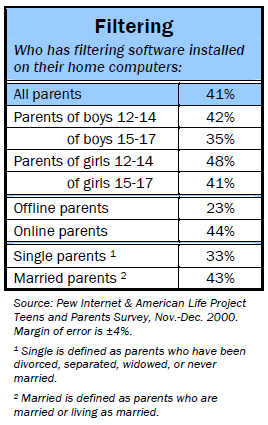

To combat their concerns, many parents, especially parents of younger teens, turn to filtering software or controls through their Internet Service Provider to restrict what their children can access online. Despite the flaws of filters, more than 2 in 5 parents (41%) of Net-using youth have some kind of monitoring software or use AOL’s parental controls on their home computers. Parents of younger girls are the most likely to have the software on the computer.

Many youth who do not have filtering software on their home computers cite parental trust as the reason for not filtering: “I don’t have any restrictions, because my mother trusts me to use the Internet without getting myself into trouble,” argued a girl, 15, in an email to the Pew Internet Project. In the Greenfield group, a 16-year-old boy said, “My mom is pretty cool and doesn’t care what I do. I suppose she wouldn’t like it if I hacked into the government, but that is the only extreme I can think of.”

Most of the teens who were contacted by the Pew Internet Project believed that parental monitoring of teenagers’ online behavior was preferable to filtering. Some felt that teaching people how to avoid bad content voluntarily would be preferable to outright control over content by the government. “I think the topic of regulation is a very difficult one,” said a 16-year-old girl in the Greenfield Online group discussion. “But I think that if we start to limit [what material is online], we will end up in a society that we really don’t want.”

Boys and adult content

Overall, 15% of online teens say they have lied about their age to gain access to a Web site – an action that is often required in gaining access to pornographic sites. A fifth of all boys (19%) ages 12-17 have done this, compared to 11% of teen girls. And fully one quarter of boys ages 15-17 have said they were older than they are in order to gain access to a Web site. Teens with several years of Internet experience are more likely than newcomers to have lied about their age to gain access to a Web site.

This is comparable to the reported use of pornographic sites by adults. Some 15% of adults say they have visited adult Web sites. Some 23% of men say they have done so and 7% of women say they have done so. Getting access to adult sites is most popular among men ages 18-29 and it is a relatively popular activity with Internet newcomers.

A significant number of the teens we engaged in the Greenfield Online group discussion and in other email exchanges reported that they had gotten unwanted email and instant messages from pornographers. “Just yesterday I was mail bombed with a porno advertisement,” wrote one boy, 16, in the Greenfield Online group discussion. “You know, I really enjoy having to receive 4260 porno advertisements. *sigh* oh well, it’s blocked now. I really hate spam mail.”

Beyond porn sites and spam, sex has another place on the Net. Some of the teens in the Greenfield Online group, when asked about things that make them uncomfortable online, mentioned cybering. It is the online equivalent of phone sex or being solicited for online sexually suggestive talk by strangers. Most were either blasé about it, or found it “creepy.” Said one girl, 15, “I feel uncomfortable a lot when people I don’t know IM me and want to know private things about me or want to cyber or whatever. I usually just block people when this happens.” Another boy, 16 stated: “Cybering is the most pointless thing in the world. It is simply typing letters and knowing that the other party is either: A.) Getting off to your message B.) Someone you know playing a joke on you or C.) (and most disturbing) All of the above.”