A general portrait of wired teens

“I multi-task every single second I am online. At this very moment,

I am watching TV, checking my email every two

minutes, reading a newsgroup about who shot JFK,

burning some music to a CD and writing this message.”

— 17-year-old boy

Introduction

The Internet is the telephone, television, game console, and radio wrapped up in one for most teenagers and that means it has become a major “player” in many American families. Teens go online to chat with their friends, kill boredom, see the wider world, and follow the latest trends. Many enjoy doing all those things at the same time during their online sessions. Multitasking is their way of life. And the emotional hallmark of that life is enthusiasm for the new ways the Internet lets them connect with friends, expand their social networks, explore their identities, and learn new things.

“The Net is an AWESOME thing,” wrote a 15-year-old boy in the Greenfield Online discussion group (the same group to which the introductory remark for this section was also made). “Who would have thought that within the 20th century, a ‘supertool’ could be created, a tool that allows us to talk to people in other states without the long distance charges, a tool that allows us to purchase products without having to go to the store, a tool that gets information about almost any topic without having to go to the library. The Internet is an amazing invention, one that opens the door to mind-boggling possibilities. As a friend of mine would probably say, ‘The Internet RULES!!!!!!!’”

Among the many striking things about teens’ use of the Internet is the way they have adapted instant messaging technologies to their own purposes. The majority of teenagers have embraced instant messaging in a way that adults have not, and many use it as the main way to conduct most mundane as well as the most emotionally fraught and important conversations of their daily lives. They have invented a new hieroglyphics of emoticons to add context and meaning to their messages and a growing list of abbreviations to help them speed their way through multiple, simultaneous online conversations.

Many teenagers use instant messaging to communicate with teachers and classmates about schoolwork or projects. Significant numbers use it along with email to conduct romantic relationships. A notable proportion of online teens have used instant messages to ask someone out and to break up with someone. Some teens use IM to play jokes on friends and tricks on enemies. Instant messaging has permeated teen culture to such an extent that for some “message me later” has replaced “call me.” A portion of teens say they have given out their user name instead of phone number to new friends or potential dates. Many believe that instant messaging allows them to stay in touch with people they would not otherwise contact – for instance, those who are only casual acquaintances, or those who live outside their communities.

American adults observe children’s use of the Internet with equal parts wonder and worry. The vast majority of teenagers (64%) and their parents (66%) agree that teens know more than their parents about using the Internet. At the same time, there is concern among adults that children’s access to vast stores of information, some of it useful, some of it informative but some of it lurid, some of it hateful, some of it violent, and some of it disgusting, could warp or harm children. In addition, some adults fear that the same technology that allows their children to communicate instantaneously with explorers in the Artic, access paintings in the Louvre, hear traditional music from Brazil, and examine texts in Cantonese, can allow strangers to seek out, exploit, or even harm their children.

These ambivalent attitudes carry over into policy matters. Computer use among children is encouraged through public funds and donations to schools and community centers across the country. Simultaneously, federal policy makers have tried several ways to protect children from accessing Internet content that is deemed inappropriate or harmful. The first attempt at lawmaking, the Communications Decency Act (CDA) in 1996, was ruled unconstitutional in federal court. The next two attempts, the 1998 Child Online Protection Act (COPA) and the 2000 Children’s Internet Protection Act (CIPA), have run into significant legal challenges.

Legislation in Washington has covered more than pornography. In 1998, lawmakers approved the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA), which requires Web sites to get verifiable parental consent before collecting personal information from children under 13. COPPA also requires affected sites to post clear and prominent privacy guidelines, though some privacy advocates say the law still does not go far enough.

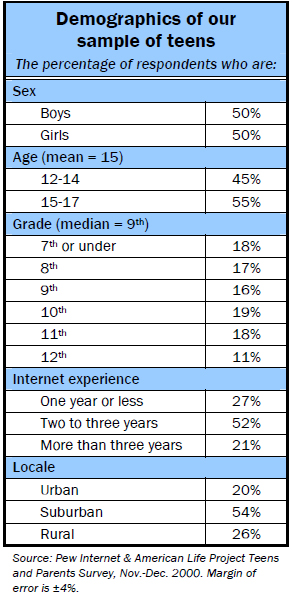

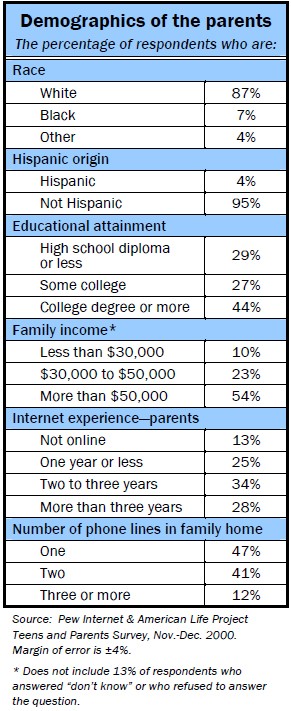

In the midst of all this concern and legislative activity, there have been few national studies of what children actually do online. In late 2000, the Pew Internet & American Life Project surveyed 754 youth ages 12 through 17 who go online, and an equal number of their parents (of whom 87% go online) to discover how youth and their parents have incorporated Internet tools into their lives. The project also conducted an online threaded group discussion in February with 21 teenagers who were brought together from a panel of Internet users developed by Greenfield Online. To prepare for that research, we conducted email interviews with 16 children from the Washington, D.C. suburbs in October 2000.

A general portrait of wired teens

Our survey work in late 20003 shows that 45% of all American children under the age of 18 go online. Almost three-quarters (73%) of those between 12 and 17 go online. In contrast, 29% of children 11 or younger go online. Our sample of 754 teens contained a roughly equal number of boys and girls. The average age that they first started using the Internet was 13, and the average length of time they have been online is 2.5 years. In 13% of these families, the children go online, but the parents do not, in part because some children have their primary access outside the home, for instance, in school or at the home of a friend.

The families in our sample, selected because their children go online, are relatively upscale: 54% have a yearly income of more than $50,000 (compared to 35% of all American parents); 44% are college graduates (compared to 27% of parents in the overall population). Our sample is slightly older than the population of all online parents, mainly because parents of children who are 12 to 17 are generally older than parents of younger children, who would all be included in a general sample of online parents.

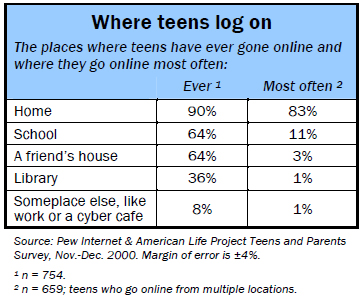

Most online teens (87%) say they go online from multiple locations. The vast majority (83%) report that their primary access is from home. Another 11% say they go online most often at school and another 3% say they go online most from a friend’s house. Two percent say that their primary connection is from someplace else, like the library, work, or an Internet café. Almost two-thirds have gone online at school at one time or another and another two-thirds have ever gone online at a friend’s house. More than a third have gone online from a library.

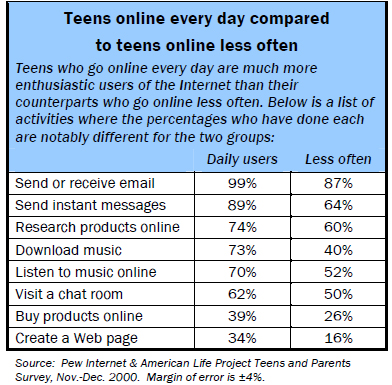

Many teenagers are heavy, enthusiastic users of the Internet, though with busy schedules full of activities, clubs, sports, jobs and homework, teens are actually less likely to go online on a typical day than adult users. We found that 42% of all online teens go online every day, compared to 59% of wired adults who are online on a typical day.4 Another third of teens (33%) say they go online a couple of times a week. Teens with several years’ online experience are more likely than newcomers to be heavy users of the Internet, and older teens are more likely than younger teens to be the most fervent users. Indeed, the older a teenager gets, the more likely it is that he will be a frequent Internet user. There is a notable change in Internet use between middle school students and high school students: About half of high school students say they use the Internet every day, compared to about a third of middle school students.

There is also a close association between the enthusiasm for the Internet that parents have and the zeal of their children. The longer a parent’s experience online and the heavier her use of the Internet is, the more likely it is that her child will be a heavy user of the Internet.

When teens are logged on, they are often multi-tasking, simultaneously emailing, instant messaging, surfing the Web, and if they are fortunate enough to have two phone lines, a cell phone, or a broadband connection, talking on the phone, too. “I do so many things at once,” acknowledged one 15-year-old girl in the Greenfield Online group discussion. “I’m always talking to people through instant messenger and then I’ll be checking email or doing homework or playing games AND talking on the phone at the same time.” Another girl, 17, from the same group explained, “I get bored if it’s not all going at once, because everything has gaps – waiting for someone to respond to an IM, waiting for a website to come up, commercials on TV, etc.”

For these teenagers, use of the Internet is often a social event. Fully 83% say they have gone online with a group of others clustered around the computer and it is not uncommon for one group of teens to be instant messaging another group of teens convened at another computer. More than half of online teens (52%) say they have logged on with their siblings at one time or another.

If the Net were not part of their lives, teens say they would watch more TV, read more, talk on the phone more, spend more time with their friends, join more clubs, and study more. “I don’t even remember what I used to do when I did not go online,” reported a 17-year-old girl in the Greenfield Online group discussion. “Sometimes I’m just so bored when I can’t use the computer.” Another 16-year-old girl added: “If I weren’t online I’d probably be reading or bored out of my mind. I used to watch a lot of TV, but I think that even human interaction in front of a computer screen is better than mind numbing TV.”

As we pointed out in our report titled Who’s Not Online, parents are more likely to go online than other adults, in part, we suspect, because their children cajole, pull, push or otherwise introduce them to the Internet. However, this role reversal in which children teach their parents might be changing as more parents learn about the Net before their children. Younger teens’ parents are more likely to introduce their children to the Net, rather than the current pattern of older teens taking their parents and families online.

Teens would miss the Internet

The respondents to our survey believe the Web is an information resource, an entertainment utility, and a tool for social connection. Three-quarters of online teens say that they would miss the Web some or a lot if they no longer had access. This matches the enthusiasm of their parents – an equal proportion of their mothers and fathers say they would miss the Internet if it were cut off from them. “If I could not go online any more then I would miss all the opportunities the web has,” noted one 15-year-old boy in the Greenfield Online group discussion. “It has everything at your fingertips including: unlimited information, instant messenger, email and games.”

For some, life without the Internet would be generally “harder and more complicated,” as one 17-year-old girl said in the Greenfield Online session. Heavy users among teens are the most likely to say they would miss going online “a lot” if Internet access were denied them. Ninety percent of teens who log onto the Internet every day say they would miss going online a lot or some. By comparison, 65% of teens who go online less frequently say they would miss it.

Parents worry, teens shake it off

This level of attachment to the technology worries many older Americans. Close to half of parents (45%) say they believe “a lot” or “some” that the Internet can lead young people to do harmful or dangerous things. After the shootings at Columbine High school in Colorado in 1999, many expressed concern that the unique capabilities of the Internet had a role in inciting and abetting violence in teens – a concern most memorably summed up by candidate George W. Bush in a presidential election debate on October 11, 2000. He worried during the debate that “a child can walk in and have their hearts turn dark as a result of being on the Internet.”5

But the teenagers asked about this by the Pew Internet Project were relatively unconcerned. When asked if they thought that the Internet led teens to do dangerous or harmful things, the greatest number of teens themselves (37%) answered “only a little” and another 28% said “not at all.” Even though they think that the Internet can in some instances lead to harmful behavior, online teens generally are less worried than their parents. And they do not want limits placed on the information that can be accessed. “Information is power and can be used either way, for good or bad,” argued a 16-year-old boy in the Greenfield Online group discussion. “It is impractical to have limitations set up on something as large as the Internet. People have that power [to impose limitations], so they choose how they use it. If a child sees something he’s not supposed to, then he’s not ready for the environment you’ve placed him in.”

Teens who are the heaviest Internet users are the least worried about its impact. Does the Internet lead young people to do dangerous or harmful things? Some 34% of daily Internet users in our sample answered “not at all” and that compares to 23% of those who go online less often who had the same response.