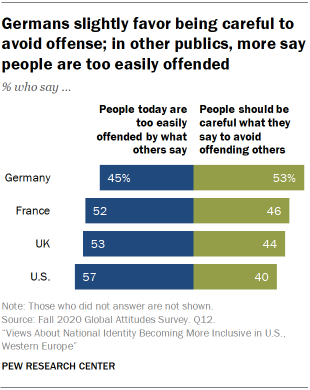

In all three European countries surveyed, respondents are closely divided over whether people today are too easily offended or whether people should be careful what they say to avoid offending others. However, only four-in-ten Americans think people should be careful what they say to avoid offending others, with a majority (57%) saying people today are too easily offended by what others say.

“I think people get scared to be passionate about being British these days because you get labeled as being a racist.”

–Man, 40, Birmingham, Right Leaver

Those ages 65 or older in France and Germany are more likely than those ages 18 to 29 to say people should be careful what they say to avoid offending others, while in the U.S. and UK there are no significant age differences.

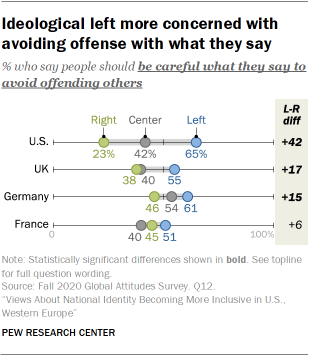

Ideological leanings play a role in how American, British and German adults feel. The ideological gap is largest in the U.S., where 65% of those on the ideological left think people should be careful to avoid offending others, compared with about one-in-four on the right, a gap of 42 percentage points. The left-right difference is 17 points in the UK and 15 points in Germany.

“There are all these things that growing up you just accepted it as that’s the name of that place. You don’t know what it is. And when you actually find out who that person was or what they were responsible for. I mean times were different and I understand that there were different considerations, but we know now that that was all wrong. It was wrong and I think it should be addressed.”

–Woman, 38, Edinburgh, Left Remainer

While there is no significant difference between the left and right in France, those in the ideological center are less likely than those on the ideological left to think people should be careful what they say to avoid offending others.

In the U.S., these ideological differences are closely related to partisanship. Six-in-ten Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents say people should be careful what they say to avoid offending others, while only 17% of Republicans and GOP-leaners say the same. Women in the U.S. are also more likely to think people should be careful what they say than men.

In the UK, those who identify as Remainers are much more likely than those who identify as Leavers to say people should be careful what they say to avoid offending others (53% vs. 27%, respectively).

In the U.S. and the UK, political cleavages drove discussion of politically correct culture

Though there was no explicit question in the focus groups dealing with issues of political correctness (or “PC culture,” as the focus group participants often said), many in both the U.S. and UK brought up the topic themselves, especially when prompted to discuss the biggest issues facing the country as well as what makes them proud or embarrassed to be British or American.

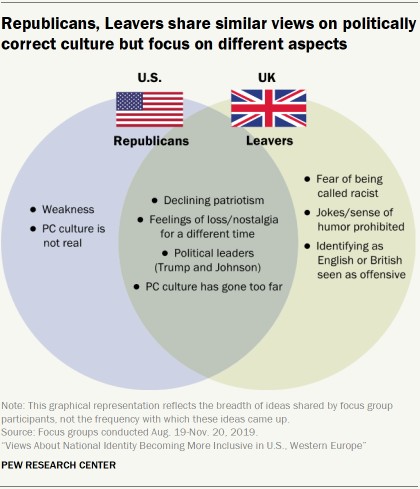

Leavers in the UK and Republicans in the U.S. overwhelmingly highlighted the negative aspects of PC culture or “cancel culture,” as they saw it. These groups stressed what they perceived as declining patriotism as a result of PC culture. Leavers pointed to stereotypes they felt existed in the UK that those who fly the St. George’s Cross or who are proud to be English are racists. Similarly, Republicans in the U.S. discussed declining respect for the American flag, the Pledge of Allegiance and “the pride of America and being an American … being dwindled away.”

Some participants pointed with nostalgia to a time when people were not “forced to tolerate things in this country.” Leavers and Republicans also brought up President Donald Trump and Prime Minister Boris Johnson in the context of PC culture. Leavers looked to Johnson as a positive example of someone who bucks the trend of PC culture, while Republicans brought up instances where President Trump and his supporters were victimized by PC culture.

Some aspects of PC culture were characterized differently in the U.S. and the UK, however. UK participants pointed to the role of media in enforcing PC culture and the prohibition of certain jokes for being racist. For instance, one London group said they “should be able to make a racist joke, but it might not be perceived as a joke.” In the U.S., one group of Republicans discussed how PC culture reflects underlying weakness among “the little snowflakes.”

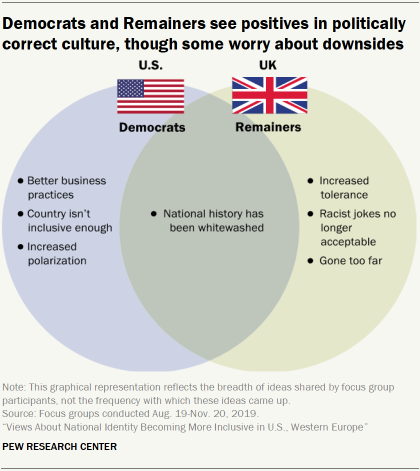

Still, not all participants viewed PC culture as a negative. Some Democrats and Remainers discussed how PC culture has led to a reckoning with national history. Edinburgh participants discussed the necessity of renaming statues and monuments (the focus groups were conducted in fall of 2019, prior to racial justice demonstrations calling for the removal of statues and monuments related to the transatlantic slave trade). One Seattle Democrat stated that shameful events “did happen and it affects our country and how people think of other people and ourselves.”

Remainer and Democratic groups also focused on different issues when it came to PC culture. Remainers thought PC culture was responsible for more tolerance in society. In Birmingham, one person discussed racist cartoons from the 1970s, arguing that “if you were to see it nowadays, you’d think ‘oof’ because things have just changed … it’s stamped out now.” Similarly, one group of Democrats argued that one “instance where cancel culture is helping” is through boycotts of certain products to combat harmful business practice abroad.

Some Democrats and Remainers were worried that PC culture could end up being a harmful force, however. Some Remainers thought PC culture had “gone too an extreme” and that it meant always being afraid of offending someone. Democrats worried that the “weaponization of difference” could exacerbate polarization.