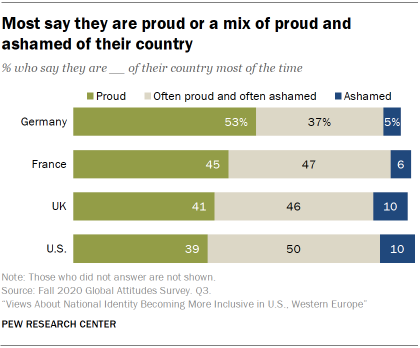

Publics are split when it comes to personal feelings of pride, shame or both for their country. Only in Germany do roughly half (53%) say they feel proud of their country most of the time. In France and the UK, roughly equal shares of the public say they are proud of their countries as say they are both proud and ashamed. In the U.S., only 39% say they are proud most of the time.

“A patriot is somebody who would be willing to die for you even if they disagree with you.”

–Man, 58, Houston, Independent

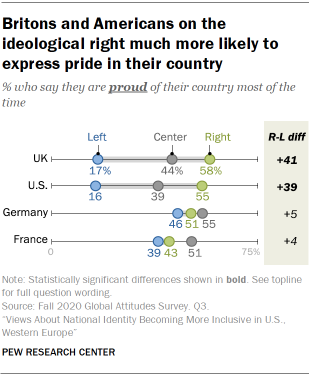

In the UK, a majority of those who place themselves on the right of the political spectrum say they are proud of the UK most of the time, 41 percentage points more likely than those who place themselves on the left. The difference between the right and the left is similarly large in America (39 points).

While relatively few across all countries say they are ashamed of their country most of the time, about one-in-five of those on the left in the U.S. and UK express this view. Similar shares of those on the left in the U.S. and UK say they are ashamed of their country as say they are proud of it.

“I like to think that patriotism is a good word, but every experience I have ever had with anybody using it has always been negative.”

–Man, 57, Seattle, Independent

Attitudes toward tradition shape personal feelings of pride among those in the U.S., the UK and France. Those who feel their country will be better off sticking to its traditions are more likely than those who feel their country will be better off if it is open to changes to say they are proud of their country.

Christians are more likely than non-Christians to say they are proud of their country in every country surveyed. (In Germany and the UK, non-Christians were less likely to respond to the question.) This divide is largest in the U.S., where 48% of Christians say they are proud of their country most of the time, compared with 22% of non-Christians.

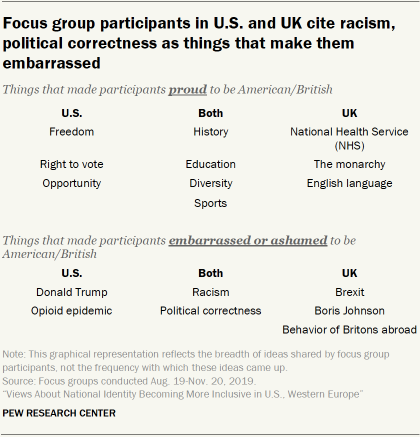

U.S. and UK focus group participants share points of pride and shame in their countries

Focus group participants in the U.S. and UK were prompted to name things that made them proud and ashamed to be American or British. Shared points of pride between participants in both countries included history, education, diversity and sports. U.S. discussions, for their part, focused more on freedom, the right to vote and being known as a land of opportunity. In Britain, the emphasis was on the National Health Service, the royal family and the widespread usage of the English language.

Participants in both countries cited being ashamed about racism and political correctness. Those on the left in both the U.S. and UK tended to cite racism as a source of shame, while those on the right mentioned “PC culture.” Both Americans and Britons also named their respective head of state as a source of embarrassment (focus groups were conducted in 2019, when Donald Trump was president). And while U.S. participants also named the opioid epidemic as a source of shame, UK groups brought up Brexit and the behavior of British people abroad.

What does it mean to be a patriot?

Focus groups conducted in 2019 across the U.S. were asked to describe a strong patriot. Often, the first characterization was someone who serves or served in the military. Participants who identified as Republican, independent and Democratic all cited military service or respect for the military in general as elements of a patriot.

In general, Republican participants tended to see “patriot” as a positive label. However, other respondents hesitated to embrace the word. For example, a discussion among independents in Houston suggested that “patriot” as a term has been co-opted and has grown to mean something more extreme or even racist. People also expressed a tension between the concept of patriotism and what they imagined patriots to look like. For example, Democratic participants often cited “patriots” as those who wore “Make America Great Again” hats, but noted this as a tension or distortion of what they viewed as patriotism in its ideal sense.

The American flag was commonly evoked in the conversation, but differently depending on political persuasion. Republican participants, for their part, described patriots as people who would stand up for the flag. (Around the time focus groups were conducted, Colin Kaepernick, a former NFL quarterback well known for kneeling during the national anthem, was in the news regarding a workout with the Atlanta Falcons.) And while participants of all political stripes discussed how patriots are likely to embrace or fly the flag, Democrats often criticized the flag as something people “hide behind.”

UK focus group participants were asked to describe someone with a strong British national identity and some echoed the concerns expressed in U.S. groups: that patriotism is often distorted to validate extreme viewpoints, such as racism. One discussion among Remain voters suggested that Leavers were more associated with “Britishness,” but in an exclusionary way, hence the need to leave Europe. A participant in a focus group of right-leaning Leavers felt she couldn’t express patriotism for risk of offending others. The example discussed by the group centered around putting up flags, another parallel to U.S. group discussion of patriots and patriotism.