People in the former Eastern bloc countries now rate their lives markedly higher than they did in 1991 shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Czechs, Poles and Slovaks report the highest levels of life satisfaction – and some of the greatest gains over the past two decades. Hungarians and Bulgarians are least likely to say they are highly satisfied with their lives, but both publics show sizeable increases since the earlier survey.

People in the former Eastern bloc countries now rate their lives markedly higher than they did in 1991 shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Czechs, Poles and Slovaks report the highest levels of life satisfaction – and some of the greatest gains over the past two decades. Hungarians and Bulgarians are least likely to say they are highly satisfied with their lives, but both publics show sizeable increases since the earlier survey.

In 1991, relatively few reported high levels of satisfaction in any of these countries – and there was little variance across demographic groups. Today, young people are more likely to be satisfied with their lives than are older people, and the better educated tend to be more satisfied than the less educated.

On balance, the people in these nations appear to be more optimistic than pessimistic about their lives over the next five years, though in several instances, they are less optimistic than they were just two years ago.

Life Satisfaction Increases

When people are asked to place themselves on a “ladder of life,” where zero represents the worst possible life and 10 the best possible life, about half (49%) of those in the Czech Republic rate their lives at least a seven, as do 44% of Poles and 43% of Slovaks. At the other end of the spectrum, just 15% of Bulgarians and Hungarians give their lives a high rating. In both of those nations, about twice as many rate their lives at the low end of the ladder (30% in Bulgaria and 32% in Hungary rate their lives from zero to three). Still, the percentages giving their lives high rankings are significantly higher than in 1991, when only 4% of Bulgarians and 8% of Hungarians gave their lives a high rating.

When people are asked to place themselves on a “ladder of life,” where zero represents the worst possible life and 10 the best possible life, about half (49%) of those in the Czech Republic rate their lives at least a seven, as do 44% of Poles and 43% of Slovaks. At the other end of the spectrum, just 15% of Bulgarians and Hungarians give their lives a high rating. In both of those nations, about twice as many rate their lives at the low end of the ladder (30% in Bulgaria and 32% in Hungary rate their lives from zero to three). Still, the percentages giving their lives high rankings are significantly higher than in 1991, when only 4% of Bulgarians and 8% of Hungarians gave their lives a high rating.

At that time, an era of great social, political and economic uncertainty, the Eastern European nations all recorded relatively low levels of life satisfaction. In Poland, for example, just 12% rated their lives near the top of the ladder. That percentage has increased by 32 points. In Russia, just 7% rated their lives in the upper tier in 1991. Now, 35% say their life satisfaction rates in the top tier.

At that time, an era of great social, political and economic uncertainty, the Eastern European nations all recorded relatively low levels of life satisfaction. In Poland, for example, just 12% rated their lives near the top of the ladder. That percentage has increased by 32 points. In Russia, just 7% rated their lives in the upper tier in 1991. Now, 35% say their life satisfaction rates in the top tier.

Ratings in Germany show both the relative stability of satisfaction levels in the country’s west and the large changes that have taken place in the east. Overall, 47% of Germans rate their lives at least a seven on the ladder, about the same as the 44% that did so in 1991. But in that earlier rating, the gap between east and west was large – 52% in the west rated their lives a seven or more, compared with 15% in the east. Today, 48% in the west rate their lives at least a seven, a decline of four points since 1991, while 43% in the east put their lives in that top tier, a jump of 28 points.

And, despite the global economic collapse of 2008, more people in the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Poland and Russia see themselves near the top end of the life satisfaction ladder than did so in 2007. In the Czech Republic, 42% rated their lives at seven or more in 2007, compared with 49% today. In Russia, 23% rated their lives at least a seven, compared with 35% now. In Poland, the increase was from 39% to 44%, while in Slovakia, it was from 36% to 43%. At the same time, in Ukraine, the percentage rating their lives a seven or more dropped from 32% in 2007 to 26%, while those rating their lives in the lowest group (zero to three) increased from 17% to 22%.

Larger Variations in Life Satisfaction

As the nations of the former Soviet bloc grappled with great change in the years immediately after the collapse of the Berlin Wall, small percentages in most expressed high satisfaction with their lives. In many cases, the differences among age groups, education levels, or rural and urban areas were narrow or nonexistent.

As the nations of the former Soviet bloc grappled with great change in the years immediately after the collapse of the Berlin Wall, small percentages in most expressed high satisfaction with their lives. In many cases, the differences among age groups, education levels, or rural and urban areas were narrow or nonexistent.

Today, there are sharp age gaps in life satisfaction, with younger people in most countries much more likely than older people to rate their lives at seven or higher on the ladder. The gap also has widened in many nations between those with some college education and those without it, with the better educated feeling better about their lives. And in several nations, including Russia, Ukraine, Hungary and Bulgaria, those who live in urban areas are more likely to rate their life satisfaction at high levels than are those in rural areas.

In Poland, half (50%) of those ages 18 to 29 rate their lives at seven or higher, compared with just 29% of those 65 and older. Similar patterns are evident in most of the former Soviet bloc nations. In Russia, 41% of those younger than 30 rate their lives near the top of the scale, compared with 25% of those 65 and older. By comparison, in the United States, similar percentages among the youngest and oldest groups (59% and 62%, respectively) rate their life satisfaction at seven or more.

In 1991, the age groups in Eastern Europe had much more similar outlooks than they do today. For example, in Poland, 13% of those 18 to 29 gave their lives a top-tier rating, compared with 15% of those at least 65.

In 1991, the age groups in Eastern Europe had much more similar outlooks than they do today. For example, in Poland, 13% of those 18 to 29 gave their lives a top-tier rating, compared with 15% of those at least 65.

The new survey also shows a wide gap in the satisfaction levels of those who are better educated and those who are not. In 1991, in many countries, those with some college education and those with no college experience had similar levels of personal satisfaction. In Ukraine, 7% of those with at least some college rated their lives at least a seven on the ladder of life, compared with 8% of those with no college education. Today, the percentage of those with at least some college education who rate their lives highly (38%) is double the percentage for those with no college education (19%).

In Russia, Ukraine, Bulgaria and Hungary, there is a more pronounced gap in outlook between those living in urban and rural areas than there was in 1991. In Russia, for example, 38% of those living in urban areas rate their lives near the top of the ladder, compared with 28% in rural areas. In 1991, fewer than one-in-ten Russians in urban (8%) and rural (5%) regions expressed high levels of personal satisfaction.

Numbers in Ukraine are similar. Today, 30% of those in urban areas say their lives are in the top tier, compared with 17% in rural areas. In 1991, the gap was three points (9% vs. 6%). In other nations, such as Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia, the divide remains relatively small. For example, in Poland, 14% of those in urban areas gave their lives a top rating in 1991, while 11% of those in rural areas did so. Today, 46% of Poles in urban areas say their lives are near the top of the scale, compared with 42% of those in rural areas.

Mixed Perceptions of Short-Term Progress

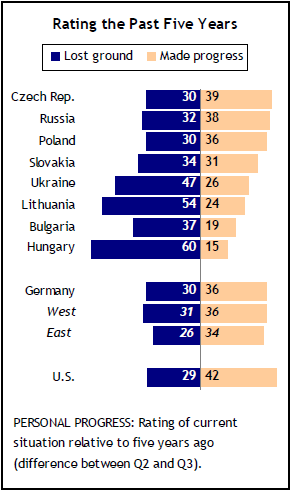

Overall, people in most of the Eastern European nations are divided over whether they are at a higher spot on the ladder of life than they were five years ago. About four-in-ten (39%) in the Czech Republic say they have made progress, while 30% say they have lost ground. Another 30% say they are at the same place on the ladder that they were five years ago. The balance is similar in Russia (38% made progress, 32% lost ground and 28% stayed the same).

Overall, people in most of the Eastern European nations are divided over whether they are at a higher spot on the ladder of life than they were five years ago. About four-in-ten (39%) in the Czech Republic say they have made progress, while 30% say they have lost ground. Another 30% say they are at the same place on the ladder that they were five years ago. The balance is similar in Russia (38% made progress, 32% lost ground and 28% stayed the same).

Meanwhile, 60% in Hungary say they have lost ground in the past five years; only 15% say they have made progress. The balance among Lithuanians and Ukrainians also is negative. In Lithuania, 54% rate their lives five years ago at a higher rung on the ladder than their lives today.

In Germany, 30% say they have lost ground, while 36% say they have made progress and 34% say they are on the same rung of the ladder as five years ago. In the former West Germany, 31% say they have lost ground, while 36% say they have made progress. In the former East Germany, 26% say they have lost ground, while 34% say they have made progress.

More Optimism Than Pessimism About Near Future

Pluralities in most of the former Eastern bloc nations expect to be at a higher point on the ladder of life five years from now. The one exception is east Germany, where 39% say they expect their lives to be about the same, 28% express optimism their lives will improve and 24% voice pessimism that their life satisfaction will decline.

Pluralities in most of the former Eastern bloc nations expect to be at a higher point on the ladder of life five years from now. The one exception is east Germany, where 39% say they expect their lives to be about the same, 28% express optimism their lives will improve and 24% voice pessimism that their life satisfaction will decline.

Still, in all of the Eastern European countries also included in the 2007 survey but one – the Czech Republic – the levels of optimism are slightly lower today than two years ago. In the Czech Republic, optimism has increased from 32% to 36%.

In Slovakia, meanwhile, the percentage expressing optimism about their situation five years from now dropped from 51% to 40%. In Ukraine, it dropped from 49% to 41%, and in Poland it dropped from 49% to 38%. In the United States, the percentage that says their lives will improve in the next five years is unchanged at 55%.

In 2007, the people of Eastern Europe were not much different in their outlook than their counterparts in Western Europe. At that time, they were generally less optimistic about the next five years than peoples in Africa and much of Asia.