Looking back at the profound political changes that took place 20 years ago, most Eastern Europeans express support for the switch to a multiparty system. However, enthusiasm for democracy has waned considerably in several countries. More than a third in Bulgaria, Russia and Hungary now say they disapprove of the change. In Ukraine, a majority feel this way.

Looking back at the profound political changes that took place 20 years ago, most Eastern Europeans express support for the switch to a multiparty system. However, enthusiasm for democracy has waned considerably in several countries. More than a third in Bulgaria, Russia and Hungary now say they disapprove of the change. In Ukraine, a majority feel this way.

At least part of this discontent stems from the perception that, while political and business leaders benefited greatly from the transition to democracy, ordinary citizens did not. Most doubt that politicians care what they think, and few believe the state is run for the benefit of all people in society.

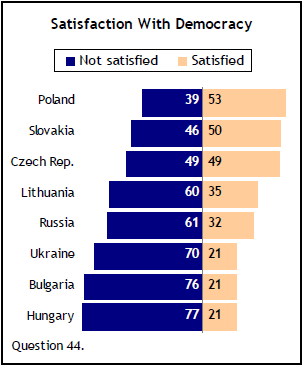

Given these frustrations, it is perhaps unsurprising that dissatisfaction with the current state of democracy is widespread in Eastern Europe. Majorities in many countries are unhappy with the way democracy is working in their countries, including roughly more than three-in-four in Hungary and Bulgaria.

Assessments are somewhat more positive in Poland, Slovakia and the Czech Republic – a majority of Poles are satisfied with democracy in their country, while Slovaks and Czechs are divided on this question. Satisfaction also tends to be higher among the young and the welleducated – groups that may be better positioned to take advantage of opportunities that have emerged from the transition to a more open society.

Less Enthusiasm for a Multiparty System

Majorities in seven of eight Eastern European countries and in the former East Germany approve of the changes that took place two decades ago, when they switched from one-party to multiparty systems. Large majorities in east Germany (85%), the Czech Republic (80%), Slovakia (71%) and Poland (70%) say they approve.

Majorities in seven of eight Eastern European countries and in the former East Germany approve of the changes that took place two decades ago, when they switched from one-party to multiparty systems. Large majorities in east Germany (85%), the Czech Republic (80%), Slovakia (71%) and Poland (70%) say they approve.

More slender majorities in Hungary (56%), Lithuania (55%), Russia (53%) and Bulgaria (52%) endorse the changes. And the share of the public that approves of the shift has declined significantly in all four nations, dropping by 24 percentage points in Bulgaria since 1991, 20 points in Lithuania, 18 points in Hungary, and eight points in Russia.

Discontent with the shift to a multiparty system is highest in Ukraine, where only 30% approve of the changes and 55% disapprove. Ukrainian views on this question are very different from 1991, when, in the final months of the Soviet Union, 72% endorsed efforts to establish a multiparty system.

The 1991 Times Mirror Center study generally found that support for democracy in Eastern Europe was highest among men, young people, the well-educated and urban dwellers. In 2009, approval for the shift to a multiparty system is consistently higher among these same groups.

The 1991 Times Mirror Center study generally found that support for democracy in Eastern Europe was highest among men, young people, the well-educated and urban dwellers. In 2009, approval for the shift to a multiparty system is consistently higher among these same groups.

Across much of Eastern Europe, men express more satisfaction with the move away from a one-party system. For instance, 78% of Polish men say they approve of the changes, compared with 63% of Polish women.

There is also a consistent relationship between age and views of multiparty democracy. In Russia, 18- to 29-year-olds (65%) are more than twice as likely as those 65 and older (27%) to approve of the change.

Approval of the switch to a multiparty system is consistently higher among people who have attended at least some college. For example, 80% of Hungarians with some college experience say they approve, while just 51% of those with less education hold that opinion. The gap between urban and rural areas is less consistent, although in Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, Lithuania and Russia, urban residents express higher rates of approval.

Changes Have Helped Business, Political Leaders

There is clear consensus in Eastern Europe that politicians and business owners have reaped more benefits from the fall of communism than have ordinary people. In all seven countries where this question was asked, more than 85% say politicians have benefited a great deal or a fair amount from the changes since the collapse of the communist system.

There is clear consensus in Eastern Europe that politicians and business owners have reaped more benefits from the fall of communism than have ordinary people. In all seven countries where this question was asked, more than 85% say politicians have benefited a great deal or a fair amount from the changes since the collapse of the communist system.

More than 80% in six of the countries say people who own businesses have benefited a great deal or a fair amount. The exception is Hungary, where a still sizable majority (63%) holds this view.

More than 80% in six of the countries say people who own businesses have benefited a great deal or a fair amount. The exception is Hungary, where a still sizable majority (63%) holds this view.

By contrast, relatively few think ordinary people have benefited from the changes. The Czech Republic is the only country in which a majority – a slim 53% majority – says ordinary people have benefited a great deal or a fair amount. About four-in-ten in Poland (42%) hold this view, while even fewer think average citizens have benefited in Russia (21%), Slovakia (21%), Hungary (17%), Bulgaria (11%) and Ukraine (10%).

Most Don’t Think State Is Run for Benefit of All

The degree to which Eastern Europeans think the current political system benefits the few rather than the many is clear when they are asked whether they agree that, generally, “the state is run for the benefit of all the people.” The only former communist country in which a majority holds this view is the Czech Republic, where 70% agree, up nine percentage points since 1991.

The share of the public who agree with this statement has also increased in Poland (by nine points) and Russia (10 points). Still, in both countries only about four-in-ten believe the state is run for the benefit of all.

Elsewhere in the region, there have been sharp declines in the share of the public who think the state is run for the good of everyone. Only 16% of Bulgarians now agree with this view, down from 55% in 1991. One-third of Slovaks take this view, down from 71% in 1991. And just 23% of Lithuanians think the government is run for the benefit of all, down from 48% in the 1991 survey.

Roughly four-in-ten Germans think the state is run to benefit all people. There is no significant difference between east and west on this question, and there has been little change in this assessment since 1991 in the county overall.

Western Europeans and Americans take somewhat more positive views of the state. About half in Britain (52%), Spain (51%) and the U.S. (51%), along with 46% in France, say the state is generally run for the benefit of all. Only 33% of Italians feel this way, although this is actually a significant improvement from 1991, when 12% held this view.

Dissatisfaction With How Democracy Is Working

Majorities in five of the eight nations that were asked to assess the current state of democracy say they are dissatisfied with how it is working in their country.

Majorities in five of the eight nations that were asked to assess the current state of democracy say they are dissatisfied with how it is working in their country.

Discontent is especially common in Hungary (77% dissatisfied), Bulgaria (76%), and Ukraine (70%). About six-in-ten in both Russia (61%) and Lithuania (60%) also say they are dissatisfied.

Poles, Slovaks and Czechs see democracy working somewhat better in their countries. Poles are more likely to express satisfaction (53%) than dissatisfaction (39%), while opinions are divided in Slovakia (50% satisfied, 46% dissatisfied) and the Czech Republic (49% satisfied, 49% dissatisfied).

Younger people generally offer a more positive assessment. Those who were children or young adults when the Iron Curtain came down are more content than older people with the current state of democracy.

The Czech Republic illustrates this pattern: 63% of 18- to 29-year-olds say they are satisfied with democracy in their country, compared with 52% of those who are 30 to 49, 44% of those who are 50 to 64 and 38% of those 65 and older.

The Czech Republic illustrates this pattern: 63% of 18- to 29-year-olds say they are satisfied with democracy in their country, compared with 52% of those who are 30 to 49, 44% of those who are 50 to 64 and 38% of those 65 and older.

Nonetheless, satisfaction is far from universal among young people. In fact, roughly four-in-ten or fewer 18- to 29-year-olds are happy with the way democracy is working in Russia (39%), Bulgaria (30%) and Ukraine (27%). And Hungarians under 30 see the situation about the same as those 65 and older. In both groups, only about one-in-five say they are satisfied.

In addition to an age gap, there is an education gap in several countries on satisfaction with democracy. Those who have attended college tend to be more satisfied with the way democracy is working than those who have not.

For example, 68% of Poles who have attended at least some college are satisfied, compared with 51% of those who have not attended college. In most cases, however, the gap is more narrow, while in Ukraine and Russia, the percentages in each group are about the same. For example, 32% of those in Russia with no college experience say they are satisfied with democracy, compared with 31% of those with at least some college.

Political Efficacy

As was the case in 1991, skepticism about politicians, and about the extent to which politicians listen to ordinary citizens, is pervasive in both Eastern and Western Europe. There is no country in which a majority agrees with the statement “most elected officials care what people like me think.” In fact, at just 39%, Britain registers the highest level of agreement with the statement, followed by the U.S. (38%) and Germany (37%).

As was the case in 1991, skepticism about politicians, and about the extent to which politicians listen to ordinary citizens, is pervasive in both Eastern and Western Europe. There is no country in which a majority agrees with the statement “most elected officials care what people like me think.” In fact, at just 39%, Britain registers the highest level of agreement with the statement, followed by the U.S. (38%) and Germany (37%).

The belief that politicians listen to ordinary people is especially rare in Eastern Europe. Even though Poles and Russians have become somewhat more likely to hold this view since 1991, only 37% in Poland and 26% in Russia think politicians care what they think.

Elsewhere, there is even greater skepticism. Only 23% of Ukrainians and 22% of Slovaks think political leaders care what they think. In Hungary, 22% have this view, down 10 percentage points from 1991.

Substantial declines have also taken place in the Czech Republic, Lithuania and Bulgaria. Just 18% of Czechs think elected officials care, down from 34% in 1991; 15% of Lithuanians hold this view, down from 30% in 1991; and 14% of Bulgarians have this opinion, a drop of seven percentage points.

By contrast, east Germans have become somewhat more likely to hold this view – 38% agree with the statement, compared with 29% in 1991. The share of Italians who believe elected officials are interested in what they think has also risen significantly, but even so, just 33% take this position.

While relatively few think politicians care what they think, most nonetheless believe that elections give ordinary citizens an opportunity to influence what government does. Majorities in most countries agree with the statement: “Voting gives people like me some say about how the government runs things.” However, in several nations these majorities are slim and in four countries less than a majority holds this view.

At least six-in-ten Bulgarians (66%), Czechs (61%) and Slovaks (60%) agree with the statement. In Slovakia the share of the public who agree has risen 14 percentage points since 1991.

Lithuanians have become much less enthusiastic about voting – 52% believe it gives them a say, compared with 74% in 1991. Less than half hold this view in Poland (47%), Ukraine (46%) and Russia (44%). Hungarians are the least likely to believe voting gives them a voice in government. Only 38% have this view, down from 49% two decades ago.

The French and Spanish express the most positive views about voting, with more than seven-in-ten in both countries saying it provides people a voice in politics. French and Spanish opinions are essentially the same on this question as they were two decades ago. About twothirds (68%) of Americans think their vote allows them to have a say in politics, down slightly from 74% in 1991.