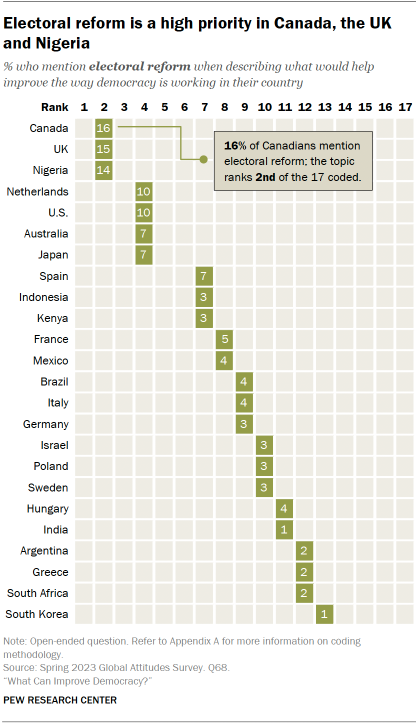

Free and fair elections are a critical element of a healthy democratic system. And in many of the 24 countries surveyed, reforming how elections and the electoral system work is a key priority. People want both large-scale, systemic changes – such as switching from first-past-the-post to proportional representation – as well as smaller-scale issues like making Election Day a holiday.

Many people link these changes to greater citizen representation, whether it’s because they allow people to vote more easily or because their votes can be more readily and accurately converted into representation.

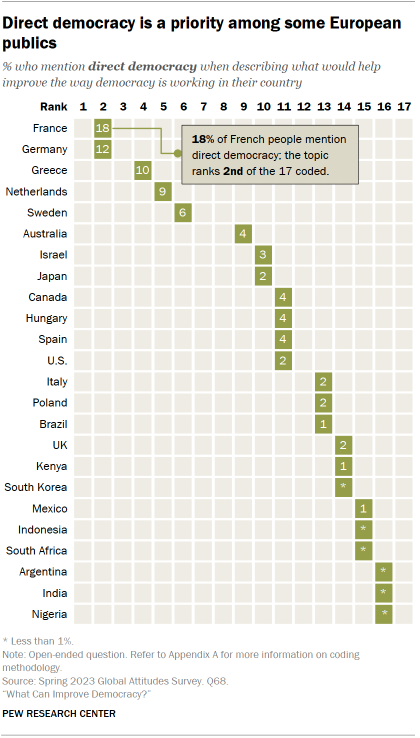

But some people take it even a step further, arguing for their country to have more direct democracy. Particularly in France and Germany, where direct democracy is the second-most suggested change, people want to have more chances to vote via referenda on topics that matter to them.

Electoral reform

Changing the electoral system appears in the top five ranked issues in seven of the 24 countries surveyed. In Canada, Nigeria and the UK, the issue ranks second among the 17 substantive topics coded.

In six countries, those who do not support the governing party or parties are more likely to mention electoral reform than those who do support such parties. In the UK, for example, where electoral reform is ranked second only to politicians, 17% of those who do not support the ruling Conservative Party mention electoral reform, compared with 6% of Conservative Party supporters. (For more information on how we classify governing party supporters, refer to Appendix D.)

However, in the U.S. and Israel, this pattern is reversed: Those who do support the governing parties are more likely than those who do not to mention electoral reform as an improvement to democracy.

“People should have the right to choose their leaders through a free and fair election.”

Woman, 20, Nigeria

Across the countries surveyed, people want to see a wide range of electoral reforms. Some of these focus on the logistics of casting votes – how and when people vote, and who is eligible. Others focus more on changing the electoral system, referencing issues like electoral thresholds and gerrymandering. And some emphasize the need to ensure free and fair elections. In Nigeria and Brazil, people who are not confident that their recent national elections were conducted fairly and accurately (as asked in a separate question in Brazil, Kenya and Nigeria) are more likely to bring up electoral reform.

Logistics of casting votes

Some of the calls for electoral reform center specifically on how ballots are cast. For example, some see benefits to electronic voting options over paper ballots, especially as a tool to protect elections: “Use modernized technology to help in security of the voting system,” said one Kenyan woman. Others see electronic ballots as an issue of convenience, particularly if it means one can vote from the comfort of their own house. As one Canadian man put it: “I think people should be able to vote electronically, using the internet and telephone instead of going to a polling station. It makes it more convenient.”

Still, in some places that have electronic voting, respondents raise concerns about this method. “End the electronic ballot box,” said a Brazilian woman. A man in India expressed his preference for paper ballots: “The use of electronic voting machines should be stopped and bring paper ballots back so that transparent democracy will be seen.”

For some Americans, increased access to absentee or mail-in voting is a specific electoral change they want to see: “Making vote-by-mail standard in every state, giving voters time to vote at their convenience, rather than having to miss work. It also gives them the time to research candidates at their leisure.” Others in the U.S. oppose mail-in voting: “Stop voter fraud! Go back to voting on Election Day. Enough with this all-month voting and mail-in votes,” wrote one American woman. “Stop mail-in ballots unless for military or another exempt person,” echoed a man. There are large partisan divides in U.S. views of voting methods, and more Democrats cast absentee votes than Republicans.

When people vote

People also see the need to change the frequency of elections. Some request fewer elections so that officeholders spend less of their term campaigning for reelection: One Australian man wanted to “lengthen the period between federal elections to five years.” Others want to see more elections, like a Canadian woman who said, “Do not have an election every four years; it should be every two years,” or a Nigerian woman who wanted her government to “conduct elections every two years, or frequently.” One South African woman went so far as to say, “Elections should be held every year.”

Some in the U.S. (where national elections are held on the first Tuesday after the first Monday of November) call for making Election Day a holiday. The U.S. is one of few advanced economies that does not hold elections over the weekend or designate the day a national holiday. For example, one American man said, “Create a national voting holiday to ensure every American has a chance to vote.” Another person said, “Eliminate voter suppression. Make Election Day a national holiday. Make voting as easy as mailing a letter.”

Who gets to vote

Making changes to who is allowed to participate in elections is another means people see to improve their democracy. For example, some want to alter the age at which citizens become eligible to cast their votes. For those who want to lower it, the argument centers around allowing more young people to participate in elections: “Lowering the voting age to 16, now young people have more stake in the game,” suggested a Canadian man. An American man had a similar opinion, saying, “I think lowering the age for voting would help democracy, because many teens as young as 16 already have views about policies in the U.S.”

Not all are in favor of lowering the voting age, however. As one Swedish man put it: “Raise the voting age. People at 18 need to take their electoral mandate more seriously.”

“There should be a voter’s license, and voters should take a civics test. Informed voting is the crux of democracy.”

Man, 76, Italy

Others feel voters need to pass a knowledge test in order to cast a vote. “The right to vote should be bound by educational attainment,” said a man in Hungary. An Italian man said, “Those who want to vote should pass a test of general culture before the elections.” And a woman in Sweden was specific on this policy: “One should know what you’re voting for, a little mini test so you know what you’re voting for. A driver’s license to vote.” (For more on perceived citizen responsibility, read Chapter 4.)

In some countries, though, there are calls to protect people’s existing right to vote. In the U.S., where voter suppression has become an electoral issue, several people were vocal about protecting the right to vote. “Abolish state laws that restrict voters’ rights,” suggested one American man. An Australian man focused specifically on protecting voting rights for Aboriginal people: “Ensure Indigenous voters have the opportunity to vote in all circumstances.” Certain respondents even want to enfranchise new types of voters: “Open the right to vote to all permanent residents, such as all Europeans who live in France,” said one French woman.

Mandatory voting

“To oblige every citizen to vote and influence according to law.”

Man, 68, Israel

Respondents in some places went as far as suggesting that voting in elections and referenda be required as a means to improve democracy. One Greek woman said, “All citizens should be forced to vote on very important laws and decisions for the country.” A man in the Netherlands saw mandatory voting as a way to improve voter turnout: “Compulsory voting should be reintroduced. For provincial council elections, turnout is only 50% to 60%. Introducing compulsory voting could improve this.”

Still, not everyone who lives in a country that has mandatory voting approves of it. “Don’t make it compulsory to vote for someone. That way, the people who really care will have their vote and those who don’t care won’t just pick the first person on the sheet or the one with the best name with no idea who they are voting for,” said one Australian woman. Another Australian shared a similar view: “I would like to see the scrapping of compulsory voting, as this will mean political parties will need to work harder for votes.” And, in Argentina, where voting is mandatory for most citizens, some respondents called for its overhaul – “that voting is not compulsory.”

Changing the electoral system

“Election law reform. Stop voting by region and switch to a national election where one can choose the winner based on the highest number of votes nationwide.”

Woman, 63, Japan

People also call for a different style of voting than they currently have. For example, some focus on implementing a first-past-the-post voting system (in which people vote for a single candidate and the candidate with the most votes wins). As one Australian man put it: “Introduce first-past-the-post voting, dispensing with preferential voting, as the minor parties are making every government difficult to operate.”

Other people value proportional representation, a system where politicians hold the number of seats proportional to their party’s support in the voting population. “Reintroduce the proportional representation voting system and ensure accountability by elected officials,” said a South African man. And a French woman said, “All representatives should be elected by proportional representation.”

Some expressed frustration with ballots listing a choice of parties instead of specific candidates, as in the case of a Swedish man who said, “Direct election of people, not parties. It is better to vote for a person, you know what they think.” An Australian agreed: “Enhancing the electoral process for Australians to vote for candidates, and less for their parties.”

There are also calls for things like ranked-choice voting (“Ranked-choice voting would limit extremism.”) and two-round voting (“The kind of two-round voting system would improve democracy.”).

But no one system necessarily satisfies everyone. In some countries that already have first-past-the-post voting, for example, there are requests to eliminate it: “Get rid of first-past-the-post. The electoral system needs reform so that the representation by popular votes should have some weight,” said one man in Canada. One Japanese woman said, “Abolish the single-seat constituency system,” referring to a type of voting that includes first-past-the-post, where one winner represents one electoral district.

Electoral threshold

“The electoral threshold should be raised, there should be fewer and larger parties.”

Man, 82, Netherlands

Changes to the electoral threshold, or the minimum share of votes needed for a candidate or party to provide representation, is suggested by some as a way to improve democracy – particularly among those who live in countries with low thresholds and fragmented party systems. In Israel, where the 3.25% electoral threshold leads to many parties participating in each election, one woman said, “Significantly increase the electoral threshold.”

This sentiment is echoed in the Netherlands, where the 0.67% threshold is the lowest in the world. One Dutch man said, “I think a high electoral threshold would be good. This could lead to less fragmentation and speed up decision-making.” Another Dutch man saw this change as a means to improve the overall quality of elections: “Raise the electoral threshold, so that there will be more substance. That way not everyone can just start a party.” The Dutch survey was conducted prior to November 2023 elections, in which the far-right Party for Freedom (PVV) won the most seats in the House of Representatives.

Making all votes count – or count more

Revising the borders of electoral districts is a reform some think could help increase voter representation. Gerrymandering, for example – a term coined in the U.S. to describe the practice of drawing electoral district boundaries in a way that creates an advantage for one party over another – is something that people in multiple countries flagged as a problem. For example, an Australian man said, “If we were to ban gerrymandering then each political group would have an equal chance to be elected.” In the U.S., one man said, “It would help if we got rid of gerrymandering and the Electoral College and things that suppress the majority.”

For others, voter representation is not just about physical electoral districts, but about correcting a perceived imbalance in the value of each vote. A 38-year-old Japanese man suggested “equalizing the value of votes from young people versus those of the elderly. Young people should be entitled to two votes.” This issue was also brought up in Spain: “The best thing would be one person, one vote. That is, that all votes were worth the same, that they were not counted by autonomous communities,” said one man.

The U.S. Electoral College

The Electoral College – the process by which U.S. presidential elections are decided – is a major focus of electoral reform for many Americans. One man’s response summarized this stance: “Abolition of the Electoral College to allow for direct representation of individual voters rather than allowing certain states to be overrepresented compared to their population size.”

Most of the U.S. respondents who mention the Electoral College are against the process, like one woman who said, “We need to do away with the Electoral College. It was a good idea, but now it doesn’t make sense.” For many, it’s an issue of unequal representation: “The Electoral College should go away, and potentially change how senators are allotted. Sparsely populated areas have too much influence while tens of millions of city residents essentially have no say,” said another woman.

Free and fair elections

“Have transparent voting and respect who wins. And the one who loses should help the one who won and move on.”

Man, 38, Argentina

People also call for more election integrity. For example, some feel there should be more transparency: “More openness in general election, no corruption, collusion or nepotism,” said a woman in Indonesia. Or, as a Nigerian man put it: “Let us have a free and fair election with transparency.” People are concerned about this issue in advanced economies as well, with one Canadian man saying, “Election integrity needs to be improved, and no outside interference.”

Others emphasize the importance of respecting election results. “Accept when a candidate loses the election and when a candidate is elected,” said a man in Brazil. An Israeli man put it simply: “Respect the results of the elections.”

“Monitor the processes more, so that there is no miscount.”

Woman, 23, Mexico

Improving electoral monitoring, or the use of unbiased observers to ensure that elections are free and fair, is also a key change people want: “Supervision over the counting of votes,” as a woman in Israel said.

In Mexico, where President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has sought controversial election reforms that many believe will weaken the country’s National Electoral Institute (INE), there are specific calls to “strengthen the INE instead of wanting to destroy it,” as one man said.

A Nigerian man expressed his wish for a better institutional oversight, saying, “The electoral commission should be independent and free from interference from the ruling party.” Nigeria’s electoral commission faced criticism during the February 2023 presidential election and was accused of delaying election results.

Direct democracy

“Consult the French people more often through referendums about important issues, life-changing issues.”

Woman, 49, France

For some, a form of government where the public votes directly on proposed legislation or policies is a solution to fixing democracy.

This sentiment is particularly common in European countries: In France, Germany, Greece and the Netherlands, it appears in the top five topics mentioned.

In most other countries, it is less of a priority.

In a handful of countries (Australia, Canada, France, Greece, the Netherlands and the UK), those who do not support the governing party or coalition are more likely to mention direct democracy.

French people stand out as particularly likely to mention direct democracy

In France, direct democracy is the second-most mentioned change people want to see. French people on the ideological left are more likely to bring up this topic than those on the right. Additionally, French adults who believe most elected officials don’t care what people like them think (as asked in a separate question) are twice as likely to mention direct democracy as those who say most officials care what they think.

Some in France specifically reference Article 49.3 of the French Constitution, under which the government can push legislation through the National Assembly with no legislative vote: “Article 49.3, which had been established for certain situations, is being used to force through unpopular measures,” said one man. The survey was fielded in France between February and April, a period during which Article 49.3 was used to implement controversial pension reforms. Another French man criticizing Article 49.3 saw direct democracy as a clear solution, saying, “Take into account the opinion of citizens in the form of a referendum. Ask for the citizens’ opinions to avoid passing laws in the form of 49.3.”

The Swiss model

Switzerland’s political system – in which the public is able to vote directly on constitutional initiatives and policy referenda – is perceived positively by others around the world, many of whom want their own country to emulate this model. For example, one Canadian woman said, “If people could vote on important issues like in Switzerland and make decisions on important laws, that’s a true democracy there.”

“More public participation on single important topics, just like the referendums in Switzerland.”

Man, 55, Germany

This viewpoint is particularly widespread across European respondents; many want their country’s democracy to resemble Switzerland’s. “It would be a good idea to go back and make decisions much more collegially, like the Swiss system,” said a French man. And a Swedish woman said, “More referenda on nuclear power, sexuality, NATO and the EU. Like Switzerland, which has referendums on many issues.” (The survey was conducted prior to Sweden joining NATO in March 2024.)

Referenda

Respondents in many countries highlight the benefits of more referenda, or instances where the public votes directly on an issue. For some, a key factor is the frequency of voting. One Kenyan man responded, “Citizens should have a referendum at least once in a while to decide on major issues that affect the country.” And a German woman asked that “more referendums take place.”

“More citizen participation in real decision-making. In other countries, referendums are held expressing opinions on different issues, not like here where they vote every four years.”

Man, 41, Spain

In other cases, referenda are seen as opportunities for the government to seek the public’s approval. A Mexican man explained, “Before becoming legal, reforms should pass through a citizen filter and popular consultation.” This sometimes includes ensuring that more marginalized voices get a chance to weigh in. For example, one Israeli man said, “When enacting any law, there should be a referendum where all citizens vote, whether Arabs or Jews.” And an Australian woman wished to see more perspectives reflected, calling for “more direct democracy, and more opportunities for influence by poor, multicultural and minority groups.”

In the UK, where a controversial June 2016 referendum resulted in the UK departing the European Union (known as Brexit), some still express support for direct democracy. A British woman suggested, “We need to put down more questions more polls for the public to choose new policies, new laws.” One British man even noted that a referendum could undo Brexit: “We should have a referendum that is truly reflective about Brexit and rejoining the EU.” But other Britons are more wary of direct democracy: One man said, “We should not allow the general public to make critical decisions. The general public should not be allowed to make economic decisions, for example, Brexit.”