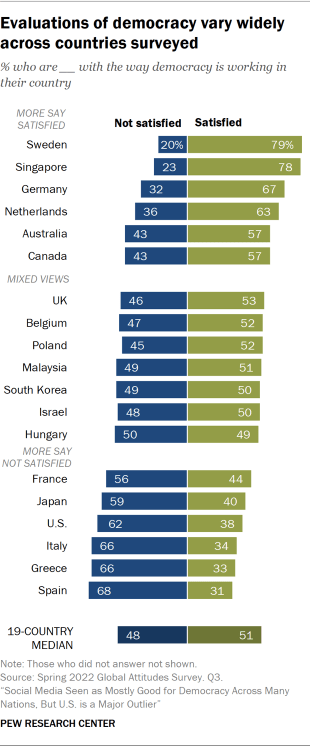

Satisfaction with democracy is largely split across the 19 countries surveyed: A median of 51% say they are satisfied with the way democracy is working in their country, while 48% are not. Satisfaction is highest in Sweden and Singapore, where nearly eight-in-ten are pleased with the way their government functions. Majorities are also satisfied in Germany, the Netherlands, Australia and Canada. Views are more evenly split in the UK, Belgium, Poland, Malaysia, South Korea, Israel and Hungary. And in France, Japan, the U.S., Italy, Greece and Spain, majorities are dissatisfied with their democracies.

In each country surveyed, those who support the governing party or coalition in power are at least 10 percentage points more likely to be satisfied with the way democracy is working (for more on governing parties, see Appendix C). The difference is largest in Hungary where 78% of those who support the governing party, Fidesz, offer positive ratings of their democracy, compared with just 27% of those who do not. (Since fielding, the governing party or coalition has changed in Australia, Israel, Italy and Sweden.)

In the U.S., Spain and Italy, even among supporters of the governing party, fewer than half are satisfied with their democracy. For example, in the U.S., 49% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents are satisfied, compared with 25% of Republicans and GOP leaners. (The survey was conducted prior to the 2022 midterm elections in the U.S.)

Income also plays a role in evaluations of democracy. In eight countries, people with higher incomes are more likely to be satisfied with the way their democracy is working than those with lower incomes.1 The opposite is true in Hungary, Poland and Malaysia, where those making less than the median income view their democracy more positively.

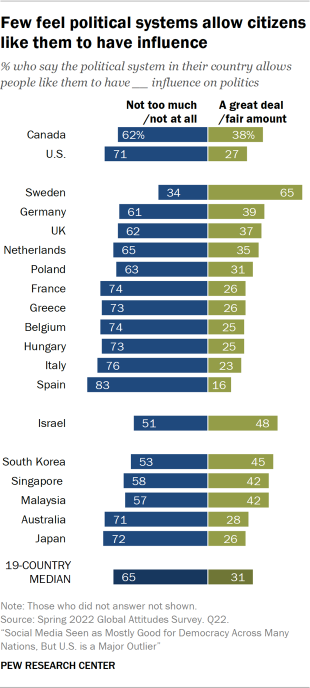

Most do not think they can influence politics in their country

Citizens are largely pessimistic about their ability to influence politics. Roughly half or more in 18 of the 19 countries surveyed say the political system in their country does not allow people like them to have an influence on politics, with a median of nearly two-thirds (65%) across all countries surveyed holding this view. Sweden is a notable exception as the only country surveyed where a majority (65%) feel confident in their ability to influence politics.

Israelis are split over whether they are able to influence politics in their country: 48% say they can have an influence on politics, while 51% say they cannot.

Support for the current governing party is a strong factor in determining perceptions of political efficacy. In nearly every country surveyed, those who support the governing party are much more likely to say they have an influence on politics than nonsupporters. This divide is greatest in Greece, where 48% of those who support the ruling New Democracy party believe the political system allows them to have a say, compared with 18% of those who do not support the party.

However, in general, so few people feel their country’s political system allows them to have an influence that in some cases, even those who support the governing party hold mostly pessimistic views. For example, while Democrats and Democratic leaners (33%) are more likely than Republicans and GOP leaners (22%) to say people like them can influence American politics, almost two-thirds (65%) of Democrats feel they have not too much or no influence at all.

Similarly, despite political gains in many European countries, supporters of right-wing populist parties in the Netherlands, Sweden, France and Germany are less likely than those who do not favor these parties to feel a sense of political efficacy (for more on populist parties, see Appendix D). In Hungary and Poland, where right-wing populist parties are in power, this pattern is reversed.

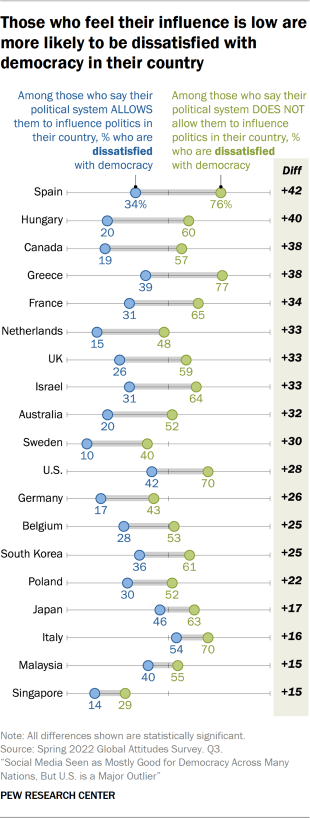

In every country surveyed, those who say their political system does not allow them to influence politics, compared with those with higher perceived political efficacy, are also much more likely to be dissatisfied with democracy. Of the Americans who say they are unable to influence politics, 70% say they are not satisfied with democracy in the U.S., compared with only 42% among those who say they have a fair amount or great deal of influence.