In the decades following the devastation and suffering of World War II, the founders of what would become the European Union sought to build a new Europe, “an ever closer union” tied together through economic and political integration, as well as a shared set of values. Despite the turmoil associated with events such as the European debt crisis, a massive influx of refugees, and Brexit, Europeans continue to believe the EU stands for noble goals.

In the decades following the devastation and suffering of World War II, the founders of what would become the European Union sought to build a new Europe, “an ever closer union” tied together through economic and political integration, as well as a shared set of values. Despite the turmoil associated with events such as the European debt crisis, a massive influx of refugees, and Brexit, Europeans continue to believe the EU stands for noble goals.

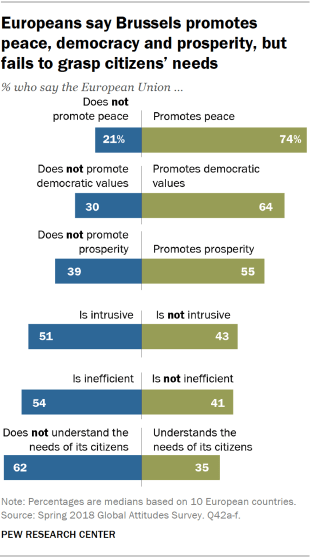

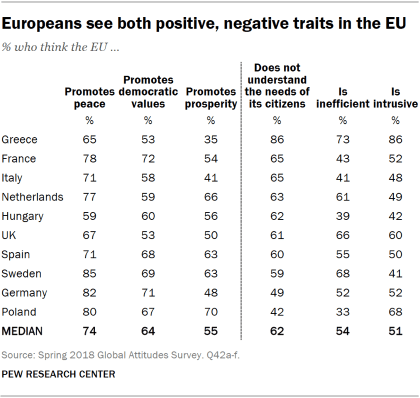

Across 10 European nations recently surveyed by Pew Research Center, a median of 74% say the EU promotes peace, and most also think it promotes democratic values and prosperity. However, Europeans also tend to describe Brussels as inefficient and intrusive, and in particular they believe the EU is out of touch – a median of 62% say it does not understand the needs of its citizens.

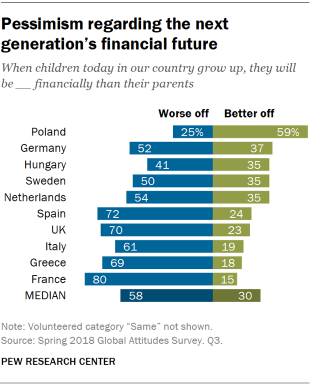

Many are also worried about the economic future. Across these 10 nations, a median of 58% believe that when children in their country grow up, they will be worse off financially than their parents; only 30% think they will be better off.

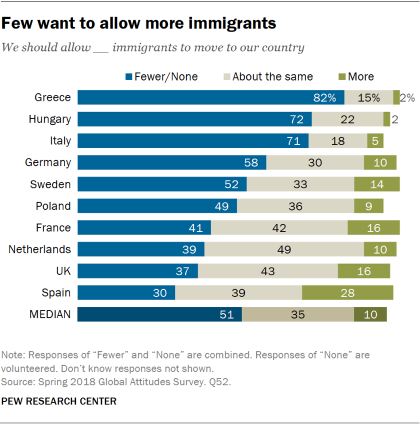

There are also strong concerns about immigration in some countries. Majorities or pluralities in most nations want fewer immigrants allowed into their country. Many believe that immigrants tend to remain distinct from the broader culture and that immigration increases the risk of terrorism.

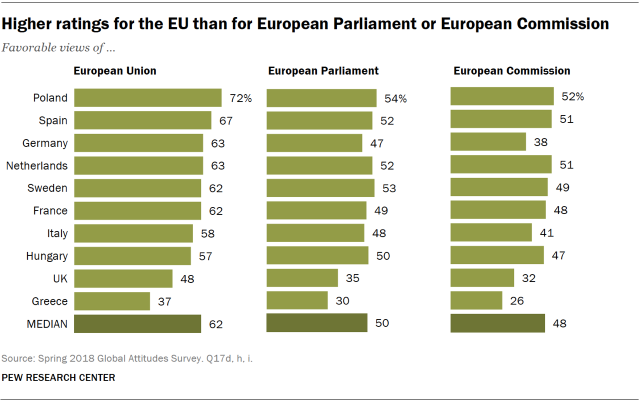

The survey also finds that views about the EU and the challenges facing Europe vary in important ways across the nations included in the study. Overall, attitudes toward the EU are largely positive. Majorities in most nations polled express a favorable opinion of the Brussels-based institution, with roughly seven-in-ten in Poland and Spain holding that view. Less than half see the EU favorably, however, in Greece and the United Kingdom (which at the time of this writing is debating its exit from the EU, originally scheduled for March 29, 2019).

And as May elections for the European Parliament approach, attitudes toward the EU-wide legislative body are mixed, although overall ratings are slightly more favorable (a median of 50%) than unfavorable (45%). The UK and Greece once again stand out for their negative assessments, while Germans and the French are almost evenly divided.

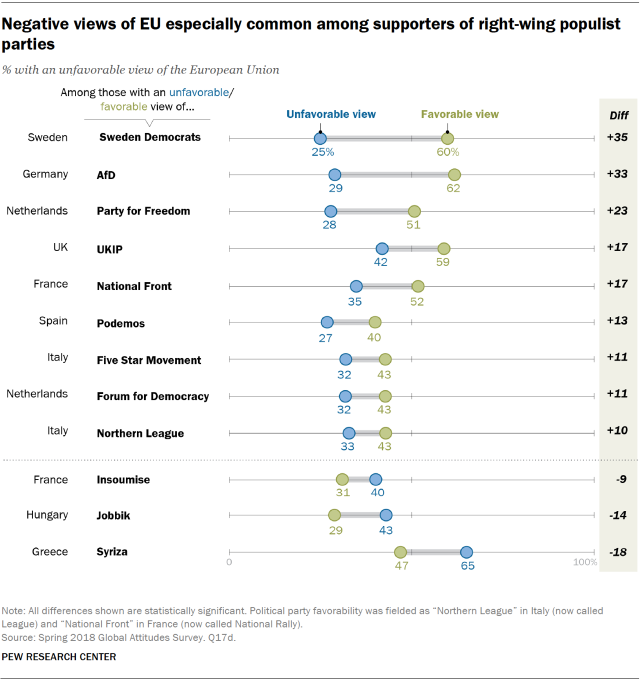

CORRECTION (March 19, 2019): The above chart has been corrected to reflect an error in the reporting on negative views of the EU among those who hold favorable and unfavorable opinions of Syriza in Greece, Jobbik in Hungary and Insoumise in France. The chart title has also been modified.

Within nations, views about the EU diverge along ideological and demographic lines, with young people and those on the political left offering more positive opinions. Meanwhile, negative views are especially common among supporters of right-wing populist parties. (For more on how populist parties are classified, see Appendix.) For example, 62% of Germans with a positive opinion of Alternative for Germany (AfD) express an unfavorable opinion of the EU, compared with just 29% of those who rate AfD negatively.

In Spain, supporters of the left-wing populist party Podemos are also particularly likely to give the EU a negative rating. However, those with positive views of left-wing populist parties in France (La France Insoumise) and Greece (Syriza) are more likely to have a favorable opinion of the EU.

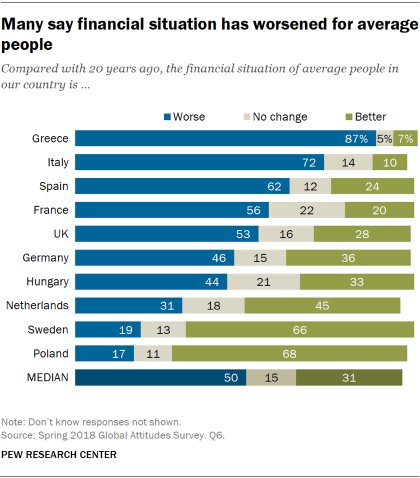

Europeans have experienced a variety of economic challenges in recent years, and the financial anxiety felt by many is clearly reflected in the survey’s findings. A remarkable number of Europeans believe the financial situation for average people in their country has not improved over the past two decades. In Greece, Italy and Spain – three southern European nations hit hard by the financial crisis – large majorities say average people are worse off than they were 20 years ago. And roughly half or more share this view in France and the UK. Two notable exceptions are Poland and Sweden, where about two-in-three believe people are generally better off financially.

Europeans have experienced a variety of economic challenges in recent years, and the financial anxiety felt by many is clearly reflected in the survey’s findings. A remarkable number of Europeans believe the financial situation for average people in their country has not improved over the past two decades. In Greece, Italy and Spain – three southern European nations hit hard by the financial crisis – large majorities say average people are worse off than they were 20 years ago. And roughly half or more share this view in France and the UK. Two notable exceptions are Poland and Sweden, where about two-in-three believe people are generally better off financially.

Views about the recent economic past differ along partisan lines in some nations. Germans who express a favorable opinion of Chancellor Angela Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU) see the past 20 years much more positively than those who rate the party negatively. Just 33% of CDU supporters say things have gotten worse, compared with 61% of those who don’t support the CDU.

Similarly, only 45% of the French with a favorable opinion of President Emmanuel Macron’s En Marche believe things have gotten worse, compared with 66% of people with an unfavorable view of En Marche.

There is also widespread pessimism about the economic future. Majorities in most of the nations polled say that when children in their country grow up, they will be worse off financially than their parents, including eight-in-ten people in France who hold this view. Poland again stands out as having more positive views: 59% of Poles are optimistic about the next generation’s economic prospects.

There is also widespread pessimism about the economic future. Majorities in most of the nations polled say that when children in their country grow up, they will be worse off financially than their parents, including eight-in-ten people in France who hold this view. Poland again stands out as having more positive views: 59% of Poles are optimistic about the next generation’s economic prospects.

While economic challenges have been a regular feature of debates about Europe’s future in recent years, immigration has also been a consistent and controversial topic. There is a strong desire in many countries for less immigration – roughly seven-in-ten or more want fewer immigrants in Greece, Hungary and Italy. This view is less common in France, the Netherlands, the UK and Spain, where roughly four-in-ten or fewer say they want less immigration.

While economic challenges have been a regular feature of debates about Europe’s future in recent years, immigration has also been a consistent and controversial topic. There is a strong desire in many countries for less immigration – roughly seven-in-ten or more want fewer immigrants in Greece, Hungary and Italy. This view is less common in France, the Netherlands, the UK and Spain, where roughly four-in-ten or fewer say they want less immigration.

Public concerns about immigration often center around culture and a perceived link to terrorism. Across the 10 nations surveyed, a median of 51% believe immigrants want to remain distinct from the broader society, while 38% think they want to adopt the nation’s customs and way of life. A median of 57% say immigration increases the risk of terrorism in their country, while 38% believe it does not.

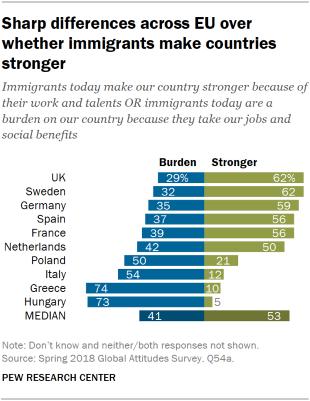

Many do see upsides to immigration, however, including the view that immigrants make their country stronger through their hard work and talents.

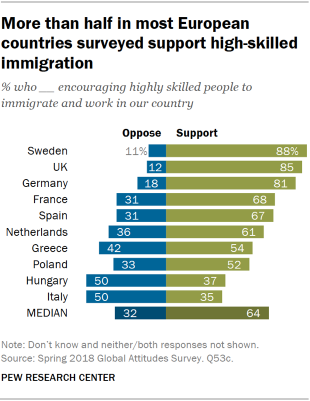

Most also support encouraging highly skilled people to come to their country for work, and a median of 77% favor taking in refugees from nations where people are fleeing violence and war.

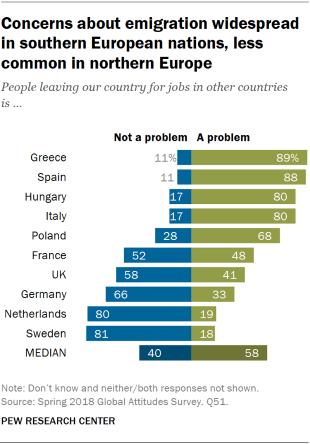

In several nations, people are worried about emigration. Eight-in-ten or more in Greece, Spain, Italy and Hungary say people leaving their country for jobs in other countries is a very big or moderately big problem, and 68% of Poles also express this opinion.

(For more on global views of immigration, see “Around the World, More Say Immigrants Are a Strength Than a Burden” and “Many worldwide oppose more migration – both into and out of their countries”).

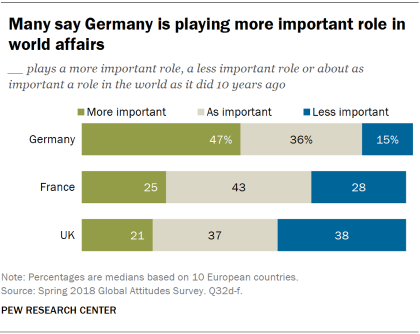

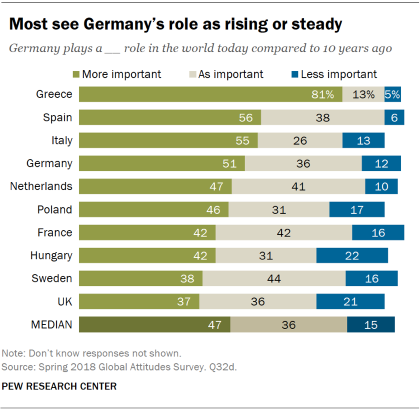

In addition to economic tumult and challenges regarding immigration, the past decade has also seen shifts in the stature of European nations on the world stage. This is particularly true of Germany. Across the 10 European nations polled, a median of 47% say Germany plays a more important role than a decade ago, while 36% believe it plays as important a role and just 15% think it is less important.

In addition to economic tumult and challenges regarding immigration, the past decade has also seen shifts in the stature of European nations on the world stage. This is particularly true of Germany. Across the 10 European nations polled, a median of 47% say Germany plays a more important role than a decade ago, while 36% believe it plays as important a role and just 15% think it is less important.

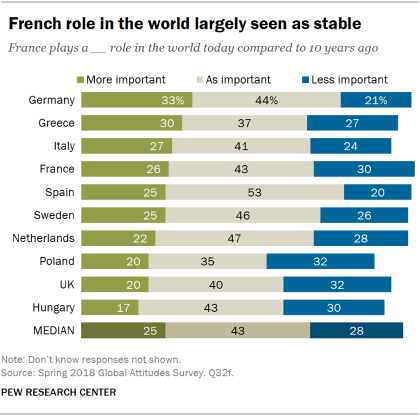

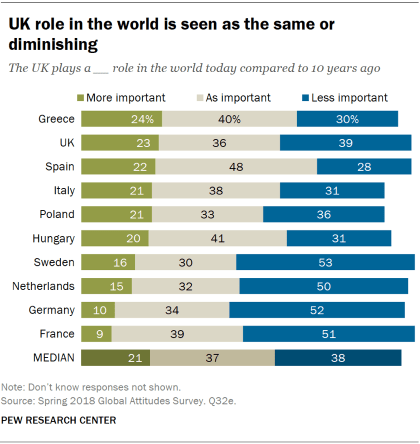

Only 25% think France plays a more important role, while a roughly equal share say it is actually less important. As it struggles with the ramifications of its Brexit vote, the UK fares the worst among the three nations tested: 38% believe the UK is less important than it was 10 years ago, while only 21% think it is more important. (For more on what people around the world think about the trajectory of major powers, see “Trump’s International Ratings Remain Low, Especially Among Key Allies.”)

These are among the major findings from a recent Pew Research Center survey conducted among 10,112 respondents in 10 countries from May 24 to July 12, 2018.

EU more popular among young people and those on the political left

Europeans’ views of the EU remain generally positive after a sharp increase in 2017. Across the 10 European states surveyed, a median of 62% hold a favorable view of the institution.

Europeans’ views of the EU remain generally positive after a sharp increase in 2017. Across the 10 European states surveyed, a median of 62% hold a favorable view of the institution.

Ratings of the EU are highest in Poland and Spain, where roughly seven-in-ten have favorable views. About six-in-ten see the EU positively in Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, France, Italy and Hungary. The UK and Greece, however, do not hold such favorable attitudes. In the UK, opinion is roughly split; 48% have a favorable opinion of the EU while 45% have an unfavorable one. And in Greece, only 37% have a positive opinion of the institution.

Opinions of the EU – both positive and negative – have remained unchanged since 2017 in all but three countries. In France, support for the EU increased from 56% in 2017 to 62% in 2018. Opinion has soured, however, in Hungary (down 10 percentage points) and the UK (down 6 points).

Opinions of the EU – both positive and negative – have remained unchanged since 2017 in all but three countries. In France, support for the EU increased from 56% in 2017 to 62% in 2018. Opinion has soured, however, in Hungary (down 10 percentage points) and the UK (down 6 points).

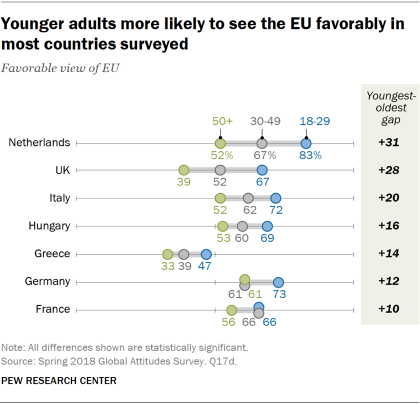

Young adults – those ages 18 to 29 – are often more likely than people ages 50 and older to have a positive opinion of the EU. This age gap is particularly large in the Netherlands, where 83% of young adults but only 52% of older adults view the EU favorably. A similarly large gap can be found in the UK, where the 2016 referendum on EU membership was broadly split along age lines.

Young adults – those ages 18 to 29 – are often more likely than people ages 50 and older to have a positive opinion of the EU. This age gap is particularly large in the Netherlands, where 83% of young adults but only 52% of older adults view the EU favorably. A similarly large gap can be found in the UK, where the 2016 referendum on EU membership was broadly split along age lines.

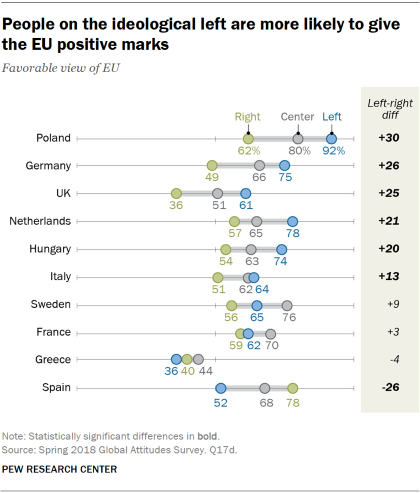

Political ideology is also frequently linked to opinion of the EU. In six of the 10 nations surveyed, people on the left of the ideological spectrum are more likely than those on the right to have a favorable attitude toward the institution. Spain, however, shows the opposite, with those on the left holding more negative views.

A similar pattern can be seen when examining sentiment among people who favor populist parties. Most of the major populist parties across Europe are on the right side of the ideological spectrum and are often strong critics of European integration. People who favor these parties in many countries are significantly less likely to have a positive view of the EU.

For example, among Swedes with a favorable view of the Sweden Democrats, 40% have a positive opinion of the EU. Among Swedes with an unfavorable view of the party, however, almost three-quarters (74%) see the EU positively.

There is a similarly large difference between Germans with a favorable view of AfD (37% view EU favorably) and those with a negative view of the party (70% view EU favorably). Both the AfD and the Sweden Democrats have proposed referendums in their respective countries to vote on EU membership.

Positive views of the EU are also less likely among those who favor right-wing populist parties in the Netherlands (Party for Freedom and Forum for Democracy), France (National Rally, formerly National Front), the UK (UKIP) and Italy (League, formerly Northern League, and Five Star Movement).

On the other end of the political spectrum, supporters of Spain’s left-wing Podemos party (58%) are also significantly less likely to view the EU positively than are non-supporters (71%).

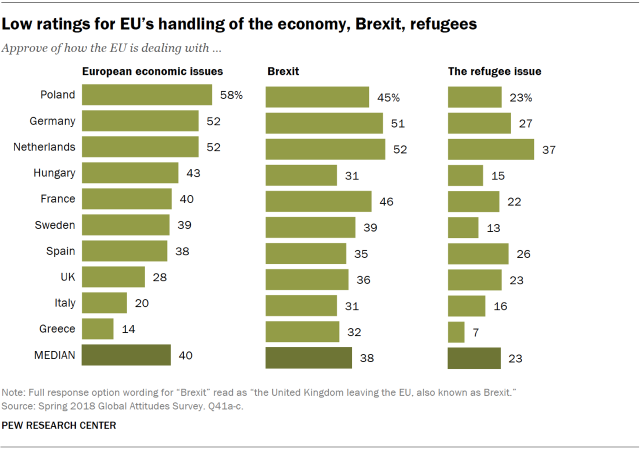

Across the countries surveyed, fewer than half say they approve of the way the EU is handling European economic issues (median of 40%), Brexit (median of 38%) and the refugee issue (median of 23%). Ratings of the EU’s performance, however, vary widely from country to country.

A majority in Poland and 52% in both Germany and the Netherlands give the EU a positive rating for its handling of European economic issues. But only one-in-five in Italy and 14% in Greece agree. Between 2017 and 2018, approval ratings related to economic issues only significantly changed in one country: Germany saw a 9-point decrease over that time (61% in 2017 compared with 52% in 2018).

Views of the way the EU is handling Brexit are generally more tepid. On the higher end of the range, about half of Dutch (52%) and Germans (51%) approve. Greeks (32%), Italians (31%) and Hungarians (31%) are the least likely to approve. Notably, more than a third of Brits (36%) say they approve of how the EU is handling Brexit. There are no differences between those on the left or the right of the political spectrum in the UK, or between those who favor or do not favor UKIP.

Overall, most Europeans do not approve of the way the EU is dealing with the refugee issue in Europe. The Netherlands is the only country where more than a third (37%) support the way the EU is dealing with this issue. Approval is lowest in Italy, Hungary, Sweden and Greece, where fewer than one-in-five approve of the way the EU has handled this issue. In several countries, approval has dropped since 2017, including a 10-point decrease in France and Hungary. Approval of the refugee issue also decreased by 6 points in the Netherlands and Germany and by 5 points in Sweden.

Views of how the EU is dealing with the refugee issue are also linked to support for right-wing populist parties. Germans who favor AfD, French who favor National Rally, Dutch who favor the Party for Freedom, Italians who favor the League and Swedes who favor the Sweden Democrats are all significantly less likely to approve of the job the EU is doing with respect to refugees in Europe.

Though ratings for the EU are generally positive, views of the European Parliament and European Commission are more divided. A median of 50% have a positive opinion of the European Parliament and 48% view the European Commission favorably. As with attitudes toward the EU more broadly, Poles have some of the most positive views of these institutions while Greeks are much more negative. Roughly two-thirds of Greeks view the European Commission (66%) and Parliament (65%) unfavorably.

Evaluations of these European institutions have stayed mostly the same since 2014, when the question was last asked, although ratings have become more favorable in Spain and Italy. For example, in Spain in 2014, roughly a third viewed the European Parliament (32%) and European Commission (30%) positively. In 2018, the share increased to around 50% for both bodies (52% and 51%, respectively).

As with views of the EU more broadly, there are ideological divides in opinion of the European Parliament and European Commission. In half of the countries surveyed – Germany, Hungary, the Netherlands, Poland and the UK – those on the ideological right are less likely to view these two institutions favorably. And people on the left of the spectrum in Spain share this negative sentiment.

What values and traits do people associate with the EU?

More than half in every country surveyed believe the EU promotes peace, and eight-in-ten or more express this view in Sweden, Germany and Poland. Roughly half or more in all 10 nations also think the EU promotes democratic values, with the French and Germans especially likely to hold this view.

More than half in every country surveyed believe the EU promotes peace, and eight-in-ten or more express this view in Sweden, Germany and Poland. Roughly half or more in all 10 nations also think the EU promotes democratic values, with the French and Germans especially likely to hold this view.

Half or more in seven nations think the EU promotes prosperity. The exceptions include Greece and Italy, two nations that suffered during the European debt crisis. Germany is another exception: The country has performed relatively well economically compared with many other EU nations over the past decade.

Opinions about the attributes of the EU have shifted in a more positive direction in France, Italy and Spain since these questions were first asked in 2014. For instance, the share of the public who think the EU promotes prosperity has risen 12 percentage points in France and 10 points in both Italy and Spain.

Across the various traits tested, supporters of right-wing populist parties are consistently more likely to associate negative characteristics with the EU. Similarly, those with less education are consistently more likely to describe the EU in negative terms.1

As fewer migrants enter Europe, anti-immigrant sentiment remains high

European publics tend to want less immigration. A median of 51% believe their country should allow fewer immigrants or none at all, while 35% think the number of immigrants should stay about the same. Just 10% want more.

European publics tend to want less immigration. A median of 51% believe their country should allow fewer immigrants or none at all, while 35% think the number of immigrants should stay about the same. Just 10% want more.

Though the number of migrant arrivals to Europe via Greece has fallen from its peak in 2015 and 2016, roughly eight-in-ten Greeks believe there should be less immigration into their country. This view is also widespread in Hungary and Italy, two nations where governing parties have embraced an anti-immigration stance.

There is little support across European publics to allow more immigrants to move to their countries. Greece (2%), Hungary (2%) and Italy (5%) are particularly resistant. Only in Spain do roughly a quarter (28%) say they should allow more immigrants to move to their country.

The European countries included in the survey hold differing views on how immigrants impact society and the economy.

The European countries included in the survey hold differing views on how immigrants impact society and the economy.

A median of 53% say that migrants make their country stronger through their hard work and talents, while 41% believe they take jobs and social benefits. Swedes and Brits are the most positive: Roughly six-in-ten think immigrant talent benefits their country, and half or more in Germany, Spain, France and the Netherlands say the same. But just 5% in Hungary express this view. Opinions on this issue have shifted with time in some countries. Since 2014, more people in France (increase of 11 percentage points), the UK (+10) and Spain (+9) share the view that immigrants strengthen their country.

A median of 53% say that migrants make their country stronger through their hard work and talents, while 41% believe they take jobs and social benefits. Swedes and Brits are the most positive: Roughly six-in-ten think immigrant talent benefits their country, and half or more in Germany, Spain, France and the Netherlands say the same. But just 5% in Hungary express this view. Opinions on this issue have shifted with time in some countries. Since 2014, more people in France (increase of 11 percentage points), the UK (+10) and Spain (+9) share the view that immigrants strengthen their country.

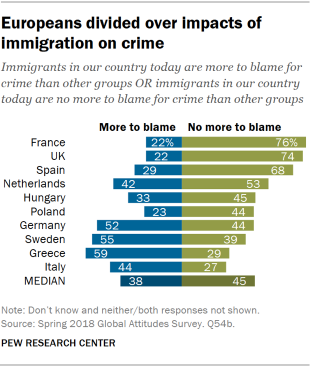

Publics are somewhat divided over the impact of immigration on crime, with a median of 38% believing that immigrants are more to blame for crime than other groups and 45% saying immigrants are no more to blame. The share who say immigrants are more responsible for crime ranges from 22% in France and the UK to 59% in Greece.

Publics are somewhat divided over the impact of immigration on crime, with a median of 38% believing that immigrants are more to blame for crime than other groups and 45% saying immigrants are no more to blame. The share who say immigrants are more responsible for crime ranges from 22% in France and the UK to 59% in Greece.

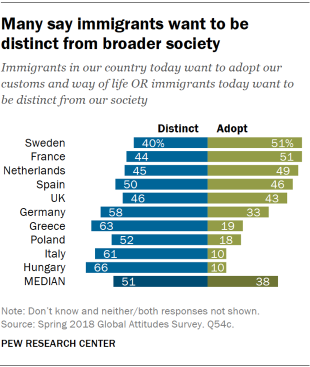

More Europeans believe immigrants want to be distinct rather than adopt their new countries’ customs. A median of 38% say migrants are willing to adopt their customs and way of life while 51% believe immigrants want to remain distinct from the broader society.

More Europeans believe immigrants want to be distinct rather than adopt their new countries’ customs. A median of 38% say migrants are willing to adopt their customs and way of life while 51% believe immigrants want to remain distinct from the broader society.

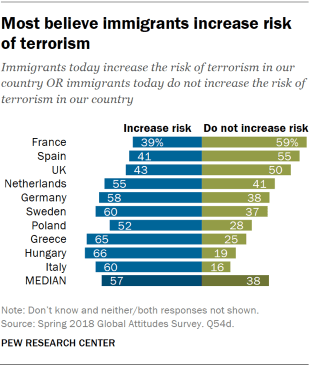

A median of 57% say immigration increases the risk of terrorism in their countries, while 38% say it has no impact. Still, in France, Spain and the UK, half or more believe immigration does not increase the odds of terrorism.

A median of 57% say immigration increases the risk of terrorism in their countries, while 38% say it has no impact. Still, in France, Spain and the UK, half or more believe immigration does not increase the odds of terrorism.

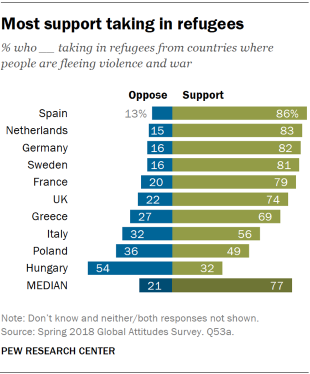

Even though many people in the nations surveyed say they want less immigration, there is considerable support for accepting both refugees who flee violence (a median of 77%) and immigrants who are highly skilled (64%). At the same time, large shares back deporting immigrants currently in the country illegally (a median of 69%).

Majorities in eight of 10 European countries favor taking in refugees, with roughly eight-in-ten or more in Spain, the Netherlands, Germany, Sweden and France expressing this view. Hungarians have the lowest support for this policy, with about a third (32%) who believe refugees should be allowed into the country.

Majorities in eight of 10 European countries favor taking in refugees, with roughly eight-in-ten or more in Spain, the Netherlands, Germany, Sweden and France expressing this view. Hungarians have the lowest support for this policy, with about a third (32%) who believe refugees should be allowed into the country.

Across 10 European countries, ideology drives views of accepting refugees. In Hungary, for example, those on the left are more likely to support taking in refugees (55%) than those on the right (26%). There are also large differences between left-right views in Greece (25 percentage-point gap), Germany (20 points), Poland (20 points) and Sweden (19 points).

When asked if highly skilled people from other nations should be encouraged to move to their country, roughly half or more in eight of 10 European countries polled support this approach. Agreement with this policy ranges from 35% in Italy to 88% in Sweden.

Education is also linked to views on this issue. In all 10 countries, those with a higher level of education are more likely than those with a lower level of education to support bringing highly skilled people into the country. For example, in France, 78% of those with a postsecondary education or more support high-skilled immigration, compared with 58% of those with a secondary education or less.

Education is also linked to views on this issue. In all 10 countries, those with a higher level of education are more likely than those with a lower level of education to support bringing highly skilled people into the country. For example, in France, 78% of those with a postsecondary education or more support high-skilled immigration, compared with 58% of those with a secondary education or less.

While Europeans are willing to consider accepting immigrants under certain circumstances, there is also a general sense that immigrants already in the country illegally should be deported. Majorities in seven of 10 countries support this policy. Greeks express the highest level of support for deportations, with 86% agreeing with this policy. Other Europeans have somewhat less support for deporting immigrants in their countries illegally. Among Italians, half favor this policy while 39% are opposed. Publics in France and Spain are split in their views of this practice.

Across the 10 European countries surveyed, publics disagree about whether people leaving for jobs in other countries is a problem. Half or more in Sweden, the Netherlands, Germany, the UK and France say this is not a problem, while majorities in Greece, Spain, Italy and Hungary express concern.

Germany’s global role seen as on the rise

There is a sense in Europe that while German power is on the rise, French and British power is stagnant or in decline.

There is a sense in Europe that while German power is on the rise, French and British power is stagnant or in decline.

Across the European countries surveyed, a median of 47% think Germany is playing a more important role in the world than it was 10 years ago. This view is most pronounced in Greece, where 81% say Germany plays a more important role, and just 5% say it has a less important role. Majorities in Spain and Italy also feel Germany plays a more important role today than it has in past.

In the Netherlands, France, Sweden and the UK, publics are divided on Germany’s world position, with roughly equal shares saying it has become more important or has remained the same.

German views of their country’s status have shifted in the last two years. About half (51%) say their role is more important, down from 62% in 2016. The share who believe their role is as important as it was a decade ago has risen from one quarter in 2016 to 36% in 2018. Younger Germans (those ages 18 to 29) are more likely than Germans ages 50 and older (64% vs. 51%) to think their country has grown in importance.

A median of 25% across the 10 European countries polled say France plays a more important role in the world. Views that France’s global position has remained the same are widespread. A plurality in eight of 10 countries say France plays as important a role as it did 10 years ago.

A median of 25% across the 10 European countries polled say France plays a more important role in the world. Views that France’s global position has remained the same are widespread. A plurality in eight of 10 countries say France plays as important a role as it did 10 years ago.

French views of their own position in the world have changed over time. Compared with 2016, more in France believe their role in the world has remained the same (43%, up from 30%), while fewer believe their role has diminished (30%, down from 46%).

In France, people who place themselves on the ideological right are more likely to say France plays a more important role than those on the left (28% vs. 17%). Similarly, those who express a favorable opinion of President Macron’s En Marche party are more likely to believe French status has grown on the world stage than are those who have a negative view of En Marche (32% vs. 19%, respectively).

Meanwhile, those ages 50 and older are more likely to say their country is playing a less important role than those 18 to 29 (36% vs. 22%).

When asked about the British role in the world today, European publics tend to believe it is static or in decline. Half or more in the Netherlands, France, Germany and Sweden think the UK plays a less important role than a decade ago. No more than about quarter in any country say the UK’s status has improved.

In the UK itself, 39% say their country’s position in the world has diminished in the last 10 years. These views are largely unchanged since 2016.

In the UK itself, 39% say their country’s position in the world has diminished in the last 10 years. These views are largely unchanged since 2016.

In the UK, those who support the populist UK Independence Party are more likely to say their country’s global status has increased, compared with those who feel unfavorably toward the party (31% vs. 20%, respectively). Meanwhile, Brits with a favorable view of the EU are more likely to say their country plays a less important role in the world than Brits with an unfavorable view of the EU (45% vs. 35%).