An engaged citizenry is often considered a sign of a healthy democracy. High levels of political and civic participation increase the likelihood that the voices of ordinary citizens will be heard in important debates, and they confer a degree of legitimacy on democratic institutions. However, in many nations around the world, much of the public is disengaged from politics.

Survey conducted in 14 countries

| Argentina | Kenya |

| Brazil | Mexico |

| Greece | Nigeria |

| Hungary | Philippines |

| Indonesia | Poland |

| Israel | South Africa |

| Italy | Tunisia |

Source: Spring 2018 Global Attitudes Survey.

To better understand public attitudes toward civic engagement, Pew Research Center conducted face-to-face surveys in 14 nations encompassing a wide range of political systems. The study, conducted in collaboration with the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) as part of their International Consortium on Closing Civic Space (iCon), includes countries from Africa, Latin America, Europe, the Middle East and Southeast Asia. Because it does not represent every region, the study cannot reflect the globe as a whole. But with 14,875 participants across such a wide variety of countries, it remains a useful snapshot of key, cross-national patterns in civic life.

The survey finds that, aside from voting, relatively few people take part in other forms of political and civic participation. Still, some types of engagement are more common among young people, those with more education, those on the political left and social network users. And certain issues – especially health care, poverty and education – are more likely than others to inspire political action. Here are eight key takeaways from the survey, which was conducted from May 20 to Aug. 12, 2018, via face-to-face interviews.

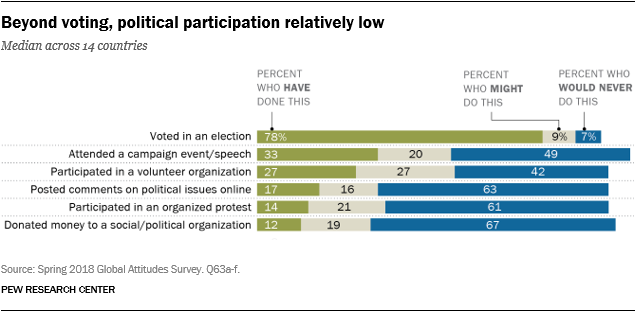

Most people vote, but other forms of participation are much less common. Across the 14 nations polled, a median of 78% say they have voted at least once in the past. Another 9% say they might vote in the future, while 7% say they would never vote.

With at least nine-in-ten reporting they have voted in the past, participation is highest in three of the four countries with compulsory voting (Brazil, Argentina and Greece). Voting is similarly high in both Indonesia (91%) and the Philippines (91%), two countries that do not have compulsory voting laws.

The lowest percentage is found in Tunisia (62%), which has only held two national elections since the Jasmine Revolution overthrew long-serving President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in 2011 and spurred the Arab Spring protests across the Middle East.

Attending a political campaign event or speech is the second most common type of participation among those surveyed – a median of 33% have done this at least once. Fewer people report participating in volunteer organizations (a median of 27%), posting comments on political issues online (17%), participating in an organized protest (14%) or donating money to a social or political organization (12%).

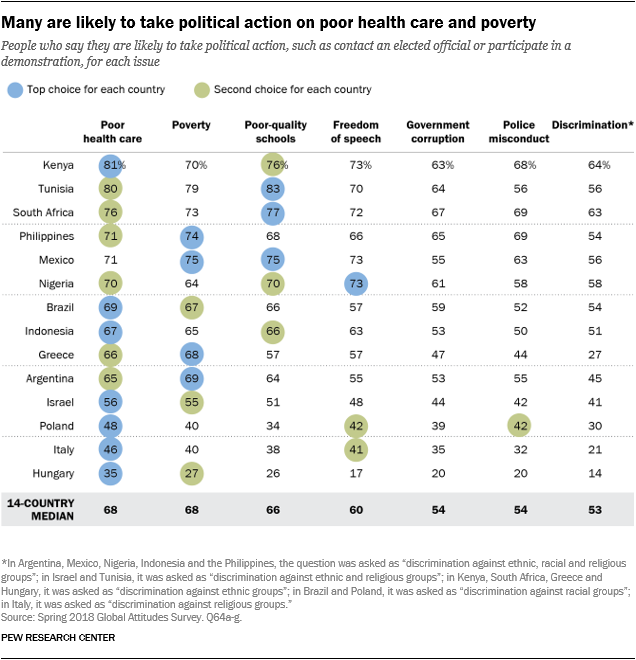

Health care, poverty and education are the top motivators for political engagement. When asked what types of issues could get them to take political action, such as contacting an elected official or participating in a demonstration, people in 13 of 14 countries rank poor health care as either their first or second choice among the issues tested. Many also place poverty and poor-quality schools among the top two issues. Overall, people are somewhat less likely to say the other issues tested could inspire them to take action. One exception is free speech, which is the top motivating issue in Nigeria and in the top two in Italy and Poland (where it is tied for second with police misconduct).

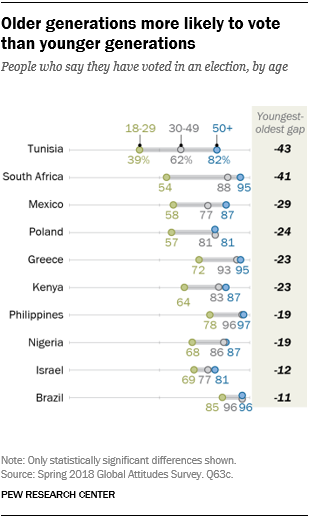

Young people vote less often. In 10 of the nations polled, people ages 50 and older are more likely than 18- to 29-year-olds to say they have voted in at least one election. The gap between the oldest and youngest respondents who have voted is more than 40 percentage points in Tunisia and South Africa, and it is more than 20 points in Mexico, Poland, Greece and Kenya.

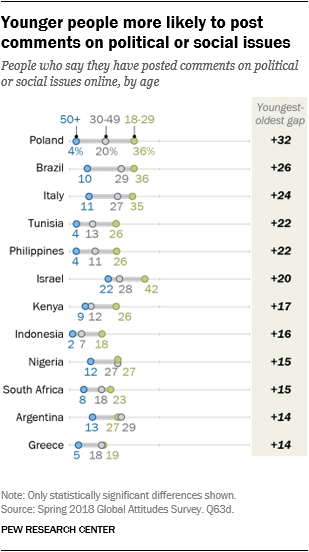

But young people are more likely to participate online. Those ages 18-29 are more likely than older adults to post comments online about social or political issues in 12 of the 14 countries surveyed. For example, 36% of Poles ages 18-29 have posted their views online, compared with only 4% of those 50 and older.

Young people are also more motivated by a variety of issues. Freedom of speech is a good example – in 10 countries, 18- to 29-year-olds are more likely than people 50 and older to say they would take political action on the issue of free speech. In Brazil, 73% of adults under 30 say they could be motivated to get politically involved over free speech, compared with 39% of those 50 and older. Young people are also more likely to take action around the issue of discrimination in 10 countries, and notable age gaps are also found on poor-quality schools, police misconduct, poverty, government corruption and poor health care.

Young people are also more motivated by a variety of issues. Freedom of speech is a good example – in 10 countries, 18- to 29-year-olds are more likely than people 50 and older to say they would take political action on the issue of free speech. In Brazil, 73% of adults under 30 say they could be motivated to get politically involved over free speech, compared with 39% of those 50 and older. Young people are also more likely to take action around the issue of discrimination in 10 countries, and notable age gaps are also found on poor-quality schools, police misconduct, poverty, government corruption and poor health care.

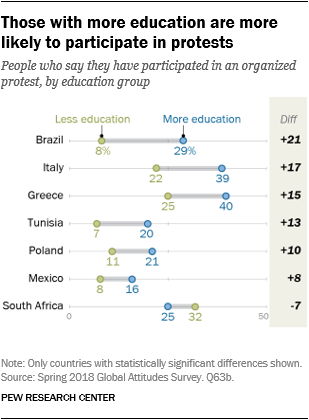

There is a strong link between education and political participation. In 13 nations, those with more education are more likely to post their views online.1 In seven nations, they are more likely to have donated money to a political or social organization. And in six countries, they are more likely to participate in a political protest. Roughly three-in-ten Brazilians with higher levels of education (29%) have participated in a protest, compared with just 8% among those with less education.

There is a strong link between education and political participation. In 13 nations, those with more education are more likely to post their views online.1 In seven nations, they are more likely to have donated money to a political or social organization. And in six countries, they are more likely to participate in a political protest. Roughly three-in-ten Brazilians with higher levels of education (29%) have participated in a protest, compared with just 8% among those with less education.

People with more education are also consistently more likely to be motivated by certain issues. This is especially true regarding free speech: In 11 countries, people with higher levels of education are more likely to say they could be motivated to take political action on free speech issues. Poverty is the one issue where there are relatively few differences between those who have more education and those with less education.

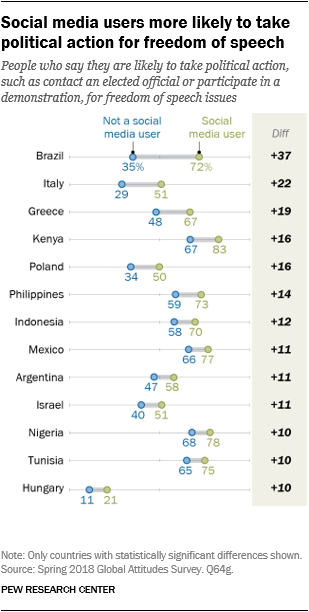

Social networking usage is linked to greater engagement on issues. People who use online social networking sites are particularly likely to take political action across the full range of issues included on the survey. For instance, in 13 of 14 countries, people who use social networking sites are more likely than those who don’t to say they might take political action on the issue of free speech. As a group, social networkers tend to be younger and more educated than those who do not engage in social networking.

Social networking usage is linked to greater engagement on issues. People who use online social networking sites are particularly likely to take political action across the full range of issues included on the survey. For instance, in 13 of 14 countries, people who use social networking sites are more likely than those who don’t to say they might take political action on the issue of free speech. As a group, social networkers tend to be younger and more educated than those who do not engage in social networking.

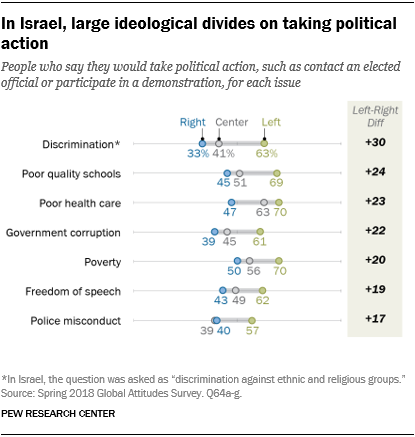

In some cases, people on the political left are more likely than those on the right to take action. In eight of the countries in the study, respondents were asked to place themselves on a left-right ideological scale. In several countries, those who put themselves on the left side of the political spectrum are more likely to take part in protests and be motivated to participate by the issues of free speech and police misconduct. Israel stands out as a country where ideological differences are especially common – every issue tested is more motivating to those on the left than to those on the right. Fully 63% of Israelis on the political left, for example, say they would likely take political action on the issue of discrimination, compared with just 33% of those on the right.

In some cases, people on the political left are more likely than those on the right to take action. In eight of the countries in the study, respondents were asked to place themselves on a left-right ideological scale. In several countries, those who put themselves on the left side of the political spectrum are more likely to take part in protests and be motivated to participate by the issues of free speech and police misconduct. Israel stands out as a country where ideological differences are especially common – every issue tested is more motivating to those on the left than to those on the right. Fully 63% of Israelis on the political left, for example, say they would likely take political action on the issue of discrimination, compared with just 33% of those on the right.