As Kenyans face the prospect of a contentious national election next year, more than half say they are dissatisfied with their country’s direction and the national economy. Besides economic concerns, government corruption is broadly viewed as a major problem in the country. And while Kenyans name corruption as one of the top priorities to address, they see little hope for substantial improvement. Moreover, the ethnic divide over these issues runs deep, with the Kalenjin and Kikuyu people much more satisfied with current conditions than the Luhya and Luo.

Despite these concerns about key development challenges in their country, Kenyans remain optimistic for the future, especially people younger than 35. In particular, Kenyans think education and health care – two development issues the public names as priorities for the country – will be much better when kids today come of age. And despite widespread dissatisfaction with political corruption, a majority still says ordinary citizens can have an influence on the government.

Kenyans dissatisfied with current conditions, but say it will get better

A majority of Kenyans (56%) are dissatisfied with the way things are going in their country. Four-in-ten are happy with current conditions. While a majority remains concerned about national conditions, dissatisfaction today is much lower than it was in 2015 (75%).

A majority of Kenyans (56%) are dissatisfied with the way things are going in their country. Four-in-ten are happy with current conditions. While a majority remains concerned about national conditions, dissatisfaction today is much lower than it was in 2015 (75%).

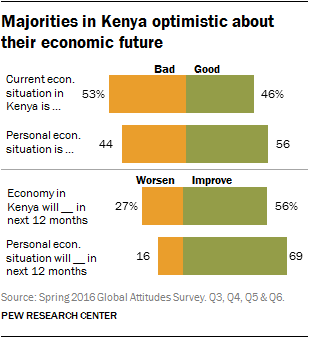

Many Kenyans say the national economy is bad (53%), including roughly a quarter (26%) who think it is very bad. Less than half (46%) say the economy is doing well. Attitudes about the economy have remained stable over the past 12 months.

Despite concerns about current national conditions, a majority of Kenyans say their personal finances are very or somewhat good (56%). This is up slightly from 2013, when half were happy with their personal economic situation.

Moreover, optimism about future finances – both national and personal – is high. More than half (56%) say the national economy will improve in the next 12 months. Kenyans are even more bullish about their personal economic circumstances, with roughly two-thirds (69%) believing their own finances will improve over the coming year. This level of economic optimism is comparable to previous years.

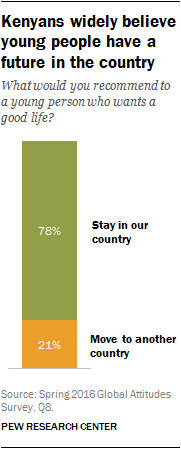

A broad majority of Kenyans (78%) would recommend that young people who want a good life stay in Kenya. Just 21% think they should move to another country. Belief that young people will do better in Kenya than elsewhere is up by 11 percentage points since 2014.

A broad majority of Kenyans (78%) would recommend that young people who want a good life stay in Kenya. Just 21% think they should move to another country. Belief that young people will do better in Kenya than elsewhere is up by 11 percentage points since 2014.

Overall, young people, those ages 18 to 34, are much more positive about their country’s financial outlook than older Kenyans. Roughly half of the younger generation (51%) says the economy is doing well, compared with just 28% of people ages 50 and older. And young people are 14 points more likely than their elders to say the economy will improve a lot over the next 12 months.

There is also wide disagreement between ethnic groups over national conditions. The Kikuyu and Kalenjin people are much more content with current conditions than the Luhya and Luo. For example, at least half of the Kikuyu (61%) and Kalenjin (53%) say the economy is doing well, while just 34% of Luhya and 19% of Luo say the same.

When it comes to personal finances, people with lower incomes are more likely than those with higher incomes to say things are currently very bad (22% vs. 13%, respectively) and to believe that they will get worse over the coming year (20% vs. 9%).

Economy, corruption and crime top concerns in Kenya

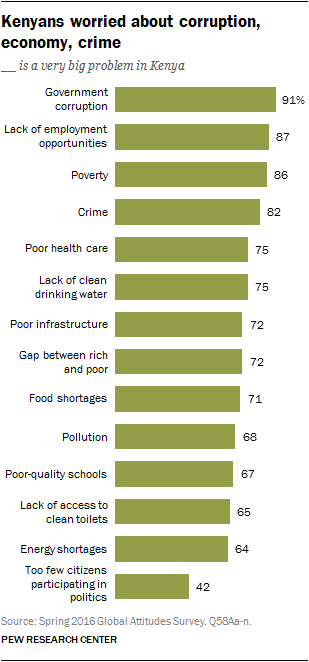

While Kenyans are generally optimistic about the future, they still say a range of development issues pose serious challenges for their country today. At the top of the list, with at least eight-in-ten Kenyans saying each is a very big problem, are government corruption (91%), economic issues such as a lack of employment opportunities (87%) and poverty (86%), and crime (82%).

While Kenyans are generally optimistic about the future, they still say a range of development issues pose serious challenges for their country today. At the top of the list, with at least eight-in-ten Kenyans saying each is a very big problem, are government corruption (91%), economic issues such as a lack of employment opportunities (87%) and poverty (86%), and crime (82%).

Somewhat lower down the list but still of widespread concern are poor health care and lack of clean drinking water (75% each). Roughly seven-in-ten say the gap between rich and poor (72%), poor infrastructure (72%) and food shortages (71%) are very big problems.

About two-thirds of Kenyans rank pollution (68%), poor-quality schools (67%) and the lack of clean toilets (65%) as a top concern. And 64% say energy shortages are a very big problem.

At the bottom of the list of concerns is the issue of too few citizens participating in politics (42% very big problem).

Income inequality ranks high on Kenyans’ list of concerns, and a majority believes it has gotten worse over the past five years (68%). Little more than one-in-ten (13%) say the gap between rich and poor has stayed the same in that time period, while 18% believe it has gotten better.

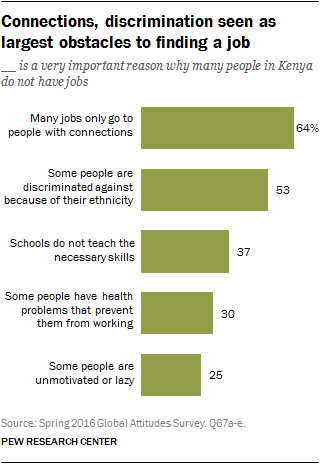

When asked why many people in the country do not have jobs, Kenyans are more likely to blame systemic factors rather than personal issues. More than half believe that jobs going to people with connections (64%) and discrimination based on ethnicity (53%) are very important reasons for a lack of employment. Nearly four-in-ten (37%) blame schools for not teaching the skills needed to get a job. Three-in-ten or fewer say health problems (30%) or personal laziness (25%) on the part of job seekers are barriers to finding work.

When asked why many people in the country do not have jobs, Kenyans are more likely to blame systemic factors rather than personal issues. More than half believe that jobs going to people with connections (64%) and discrimination based on ethnicity (53%) are very important reasons for a lack of employment. Nearly four-in-ten (37%) blame schools for not teaching the skills needed to get a job. Three-in-ten or fewer say health problems (30%) or personal laziness (25%) on the part of job seekers are barriers to finding work.

Looking outside their national borders, few Kenyans blame engagement with the global economy for the lack of employment opportunities in their own country. Just 25% say such involvement lowers wages and costs jobs in Kenya. Seven-in-ten think engagement with other nations provides their country with new markets and opportunities for growth.

Higher-income Kenyans (73%) are more likely than lower-income people (59%) to say connections are a very important reason why many people do not have jobs. Conversely, lower-income people (35%) are more likely than wealthier Kenyans (24%) to blame health problems for a lack of employment. Women and men also disagree on the relevance of health problems (35% of women say these are very important vs. 25% of men).

There is a deep divide over whether ethnic discrimination plays a role in unemployment. Majorities of the Kamba (74%) and Luo (61%) ethnic groups say discrimination is a major barrier; less than half of the Kalenjin (44%) and Kikuyu (39%) agree.

Education tops Kenyans’ priorities

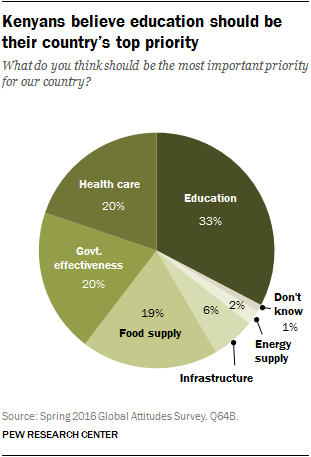

When Kenyans are asked to select from a list of six possible priorities for improving the country, 33% say education is the most important. Two-in-ten choose health care and another 20% mention government effectiveness, such as reducing corruption. A similar percentage picks agriculture and the supply of food (19%). Just 6% say infrastructure and 2% prioritize the supply of energy.

When Kenyans are asked to select from a list of six possible priorities for improving the country, 33% say education is the most important. Two-in-ten choose health care and another 20% mention government effectiveness, such as reducing corruption. A similar percentage picks agriculture and the supply of food (19%). Just 6% say infrastructure and 2% prioritize the supply of energy.

For their second most-important priority, Kenyans mention health care (27%), education (25%) or agriculture (20%). All other issues garner support from 10% or less of the public.

Health care is a higher priority for women (26%) than it is for men (15%). Men (9%), on the other hand, place a greater emphasis on improving infrastructure than do women (3%). Nonetheless, education tops the list for both women (34%) and men (32%).

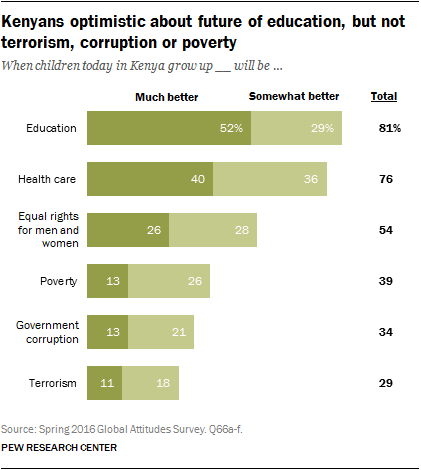

Kenyans see varied potential for future improvement across issue areas. A broad majority of Kenyans (81%) think education will be better when today’s children grow up, including 52% who say it will be much better. Similarly, 76% believe health care will have improved when the younger generation comes of age, with 40% saying it will be much better. More than half say gender equality will be better in the future as well.

Kenyans see varied potential for future improvement across issue areas. A broad majority of Kenyans (81%) think education will be better when today’s children grow up, including 52% who say it will be much better. Similarly, 76% believe health care will have improved when the younger generation comes of age, with 40% saying it will be much better. More than half say gender equality will be better in the future as well.

However, roughly four-in-ten or fewer think poverty or government corruption will be better for the next generation; just 13% of Kenyans say either of these issues will be much better. Similarly, only 29% believe terrorism will improve, including just 11% who say this concern will be much improved. Pessimism is deeply held on these three issues. Pluralities say each of these concerns will be much worse for the next generation – 47% for terrorism, 42% for government corruption and 36% for poverty.

U.S., China seen as development role models

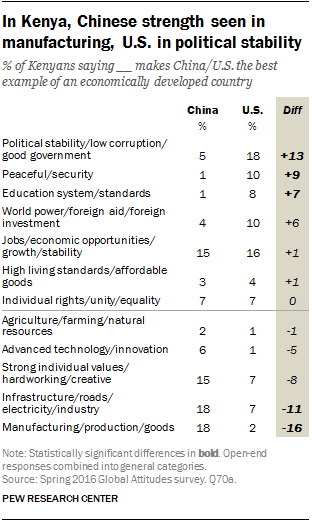

Roughly a third of Kenyans (36%) mention the U.S. as the best example of an economically developed country and another 15% say China. Japan, Tanzania and South Africa are mentioned by 4% each. No other country is named by more than 2% of respondents.

Roughly a third of Kenyans (36%) mention the U.S. as the best example of an economically developed country and another 15% say China. Japan, Tanzania and South Africa are mentioned by 4% each. No other country is named by more than 2% of respondents.

For both the U.S. and China, one of the top reasons Kenyans say they have been successful is because of economic conditions in those countries, such as employment opportunities and economic stability. However, the other drivers of economic success named by Kenyans differ considerably between the two country models. Those who admire the U.S. are more likely to mention political stability, including low levels of corruption, the presence of peace and security, and the quality of the education system. For those who name China, the top reasons named are more likely to be manufacturing and the export of products, as well as high-quality infrastructure and industry.

Kenyans say political action can be influential

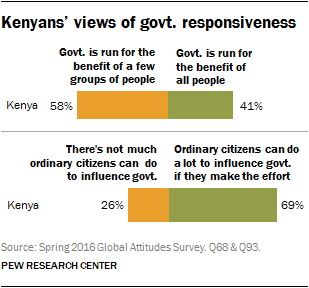

The quality of governance generally, and corruption specifically, is a major concern for most Kenyans. A majority (58%) thinks their government is run for the benefit of a few groups of people. Roughly four-in-ten think the government is run for the benefit of all. Luo (76%), Luhya (68%) and Kamba (64%) are much more likely to say the government benefits only a few groups than do the Kikuyu (49%) or Kalenjin (44%).

The quality of governance generally, and corruption specifically, is a major concern for most Kenyans. A majority (58%) thinks their government is run for the benefit of a few groups of people. Roughly four-in-ten think the government is run for the benefit of all. Luo (76%), Luhya (68%) and Kamba (64%) are much more likely to say the government benefits only a few groups than do the Kikuyu (49%) or Kalenjin (44%).

Despite these concerns, Kenyans remain optimistic about their potential to have an impact on politics. Nearly seven-in-ten say ordinary citizens can do a lot to influence the government (69%). Just 26% believe citizens have little effect. Majorities across all ethnic groups say they can have a voice in government.

Kenyans are much more likely to try to influence their government through traditional means. Voting is the most widespread political action, with nearly three-quarters saying they have voted in an election, either in the previous year or in the more distant past. Roughly half say the same about attending a political event or speech. Four-in-ten have participated in a political, charitable or religious-based volunteer organization.

Other, nontraditional forms of political activity are much less common. Just 10% of Kenyans have participated in an organized protest. Roughly one-in-ten have participated in online activities, such as posting comments online, encouraging others to take action online or signing a petition online. Among internet users, people are more likely to have either posted their own thoughts (23%) or encouraged others to take political action (20%) than they are to have signed a petition (12%).5

Other, nontraditional forms of political activity are much less common. Just 10% of Kenyans have participated in an organized protest. Roughly one-in-ten have participated in online activities, such as posting comments online, encouraging others to take action online or signing a petition online. Among internet users, people are more likely to have either posted their own thoughts (23%) or encouraged others to take political action (20%) than they are to have signed a petition (12%).5

Kenyans ages 50 and older (58%) are less optimistic than those under 35 (76%) that ordinary citizens have any influence over the government. Nonetheless, the oldest generation is more likely than the youngest to say they have voted (95% vs. 59%), attended a political event (60% vs. 42%) or participated in a volunteer organization (52% vs. 36%). The only activity that young people are more likely to have done is posting thoughts or comments online about political and social issues (16% among 18- to 34-year-olds vs. 6% of those 50+).

Health care (77%) is the top issue among the six asked about on which Kenyans say they are likely to personally take political action. This includes nearly half who say they are very likely to do so. Roughly three-quarters (74%) say they are very or somewhat likely to be active around the issue of education, and 68% express the same level of motivation about poverty.

Health care (77%) is the top issue among the six asked about on which Kenyans say they are likely to personally take political action. This includes nearly half who say they are very likely to do so. Roughly three-quarters (74%) say they are very or somewhat likely to be active around the issue of education, and 68% express the same level of motivation about poverty.

Majorities also say they would be politically active on the issues of government corruption, discrimination or police misconduct. Still, with the exception of health care, only about four-in-ten or fewer say they are very likely to do something about each issue.