China and Japan – neighboring economic and military powers – view each other with disdain, harbor mostly negative stereotypes of one another, disagree on Japan’s World War II legacy and worry about future confrontations.

China and Japan – neighboring economic and military powers – view each other with disdain, harbor mostly negative stereotypes of one another, disagree on Japan’s World War II legacy and worry about future confrontations.

The two East Asian nations have a centuries-old relationship, punctuated by major conflict and strife. Most recently, Beijing and Tokyo have been at loggerheads about sovereignty over a group of uninhabited islands in the East China Sea, called the Senkaku by the Japanese and the Diaoyu by the Chinese.

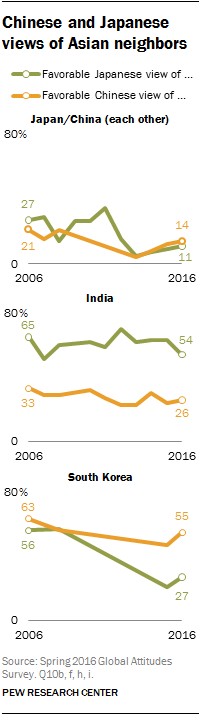

Today, only 11% of the Japanese express a favorable opinion of China, while 14% of the Chinese say they have a positive view of Japan. In both countries positive views of the other nation have decreased since 2006.

Sino-Japanese antipathy can also be seen in a regional context. Influenced by history, economic ties and current events, Asian publics’ views of each other vary widely.

Sino-Japanese antipathy can also be seen in a regional context. Influenced by history, economic ties and current events, Asian publics’ views of each other vary widely.

Australia has strong economic ties with both China and Japan. China accounts for 34% of Australia’s exports, while Japan is Australia’s second-largest export market, accounting for 18% of Australian exports. About eight-in-ten Australians (79%) voice a favorable opinion of Japan. But only 52% express positive sentiment about China.

Indians are also more positive on Japan than on China. A plurality of Indians have a favorable view of Japan (44%), while a much smaller share (22%) see Japan in a negative light. China, on the other hand, gets more negative reviews in India (36%) than positive reviews (31%). About a third of the Indian public expresses no opinion on China or Japan.

These are the key findings of a Pew Research Center survey of 7,618 respondents in four countries: China, Japan, Australia and India. The survey was conducted April 6 to May 29, 2016.

Largely negative stereotypes

Stereotypes can reveal a great deal about the assumptions, sometimes biased or prejudiced, that influence how people view members of other groups.

Stereotypes can reveal a great deal about the assumptions, sometimes biased or prejudiced, that influence how people view members of other groups.

In the case of China and Japan, publics tend to hold largely negative stereotypes of one another. The Chinese and the Japanese see each other as violent. Roughly eight-in-ten Japanese describe the Chinese as arrogant, while seven-in-ten Chinese see the Japanese in that light. Notably, about three-quarters of the Japanese say the Chinese are nationalistic. But only about four-in-ten Chinese associate that word with the Japanese. Neither public sees the other as honest.

A generation gap exists among the Japanese in their views of the Chinese. Older Japanese – those ages 50 and older – are more likely than Japanese ages 18 to 34 to see the Chinese as nationalistic. And older Japanese are less likely than the younger generation to believe that the Chinese are hardworking or modern.

History remains a neuralgic issue in Sino-Japanese relations. Seven decades after the end of World War II, the two publics have starkly differing perceptions of whether Japan has expressed adequate regret for its wartime behavior.

Roughly half the Japanese say their country has apologized sufficiently for its military actions during the 1930s and 1940s. And such sentiment is up 13 percentage points since 2006. The Chinese see this issue quite differently. Just 10% of Chinese believe Japan has apologized enough. And the difference between Japanese and Chinese sentiment has grown from 37 points to 43 points in the past decade.

Roughly half the Japanese say their country has apologized sufficiently for its military actions during the 1930s and 1940s. And such sentiment is up 13 percentage points since 2006. The Chinese see this issue quite differently. Just 10% of Chinese believe Japan has apologized enough. And the difference between Japanese and Chinese sentiment has grown from 37 points to 43 points in the past decade.

Not only do perceptions of the countries’ shared history differ, but expectations for the future of the Sino-Japanese relationship are also largely negative. Eight-in-ten Japanese (80%) and about six-in-ten Chinese (59%) are concerned that territorial disputes between China and its neighbors could lead to a military conflict.

Japan’s partisan divide

Japanese attitudes toward China are marked by partisan divides. Supporters of the country’s conservative Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) are more critical of China than are supporters of the opposition Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ). Fully 46% of Japanese who identify with the ruling LDP have a very unfavorable view of China. Only 30% of those who support the opposition DPJ share such intense negativity.

Japanese attitudes toward China are marked by partisan divides. Supporters of the country’s conservative Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) are more critical of China than are supporters of the opposition Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ). Fully 46% of Japanese who identify with the ruling LDP have a very unfavorable view of China. Only 30% of those who support the opposition DPJ share such intense negativity.

Notably, those who identify with the LDP are also more critical of South Korea than are backers of the DPJ.

LDP and DPJ supporters also differ on Chinese nationalism: DPJ adherents are far more likely than LDP backers to see the Chinese as nationalistic (87% vs. 72% respectively).

In addition, LDP supporters (59%) are more likely than DPJ adherents (47%) to believe that Japan has apologized sufficiently for its military actions in the 1930s and 1940s. For their part, DPJ supporters are much more likely to say that Japan has not apologized sufficiently. And while 22% of those with the LDP say there is nothing Tokyo needs to apologize for, just 12% of DPJ backers agree.

Dyspeptic views of each other

Just 11% of Japanese express a favorable view of China today. And over the past decade, the average favorability of China among Japanese has been just 18%.

Just 11% of Japanese express a favorable view of China today. And over the past decade, the average favorability of China among Japanese has been just 18%.

Japanese animosity toward China varies somewhat by generation. Older Japanese – those ages 50 and older – are particularly unfavorable toward China (48% very unfavorable). Japanese ages 18 to 34 are less intensely negative (32% very unfavorable).

For their part, the Chinese likewise have little regard for Japan. Today, only 14% voice a favorable opinion of their Asian neighbor, in line with the average of available data over the past decade.

Both the Japanese and the Chinese see their other major Asian neighbors more positively than they do each other, though they still often view other neighbors in a negative light as well.

More than half (54%) of Japanese have a favorable opinion of India, down from 65% in 2006.

In contrast, only 27% of Japanese express a favorable view of South Korea. The legacy of Japan’s colonial occupation of Korea remains a sore point in bilateral relations. And Seoul has recently pressed Tokyo to accept greater responsibility for “comfort women,” Korean women pressed into work as sex workers during World War II. This may explain why the 2016 favorability of South Korea in Japan is roughly half the positive Japanese sentiment (56%) expressed in 2006.

In stark contrast, 55% of Chinese voice a favorable opinion of South Korea. Such sentiment has decreased slightly from 2006 (63%).

The Chinese are far less positively disposed toward India. Just 26% hold a favorable view of their southern neighbor, with whom China has had numerous territorial disputes for more than a half century. Over the last decade Chinese opinion of India has drifted downward from 33% favorable in 2006.

Chinese-Japanese stereotypes

The Chinese and Japanese have held fairly strong and often negative stereotypes of each other for some time. And in some instances these views have worsened over the past decade.

The Chinese and Japanese have held fairly strong and often negative stereotypes of each other for some time. And in some instances these views have worsened over the past decade.

In 2006, half of Japanese viewed the Chinese as violent. In 2016, roughly seven-in-ten Japanese saw the Chinese in that negative light. In addition, fully 74% of Japanese ages 50 and older see the Chinese as violent, while 60% of Japanese ages 18 to 34 view the Chinese in that manner.

Roughly eight-in-ten Japanese associate arrogance with the Chinese. Only about two-thirds said the Chinese were arrogant a decade ago.

More than six-in-ten Japanese (64%) thought the Chinese were hardworking in 2006, but now only around four-in-ten (42%) view them in that way. Again, it is older Japanese who are more critical (although older Japanese are more likely to voice no opinion): Only 35% of Japanese ages 50 and older associate the attribute hardworking with the Chinese, while 60% of younger Japanese see the Chinese in that light.

Largely unchanged among Japanese is the belief that the Chinese are modern: 29% said that about the Chinese 10 years ago, and 25% hold that opinion today.

Japanese sentiment toward the Chinese has changed slightly on perceptions of the Chinese being nationalistic. In 2006, 82% believed the Chinese were nationalistic. Today 76% see them that way. A generation gap divides this Japanese perception: 80% of older Japanese say the Chinese are nationalistic, while 65% of younger Japanese agree. And 87% of the DPJ and 72% of the LDP supporters see the Chinese as nationalistic.

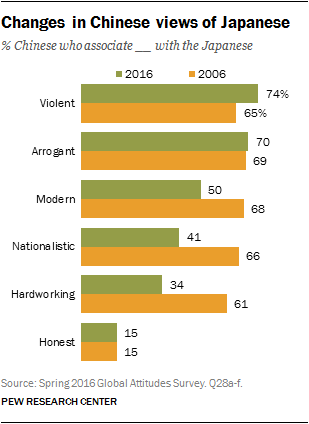

The Chinese also subscribe to negative stereotypes of the Japanese. Seven-in-ten or more Chinese associate violence (74%) and arrogance (70%) with the Japanese. The former view is up 9 percentage points since 2006.

The Chinese also subscribe to negative stereotypes of the Japanese. Seven-in-ten or more Chinese associate violence (74%) and arrogance (70%) with the Japanese. The former view is up 9 percentage points since 2006.

Only half the Chinese see the Japanese as modern, down from roughly two-thirds a decade ago. And the proportion of Chinese (34%) who see the Japanese as hardworking has nearly halved since 2006 (61%). As a point of comparison, in a 2015 Pew Research Center survey, 94% of Americans believed the Japanese to be hardworking.

At the same time, the Chinese have become less critical of Japanese nationalism. Roughly two-thirds of Chinese thought the Japanese were nationalistic in 2006; around four-in-ten see them that way today.

Notably, only 15% of the Chinese believe the Japanese are honest, unchanged from a decade ago. The Japanese hold the Chinese in a similarly low regard – 12% view them as honest – and this is roughly half the number who found the Chinese honest 10 years ago. (In the 2015 survey 71% of Americans saw the Japanese as honest.)

Strategic perceptions: Looking back, looking forward

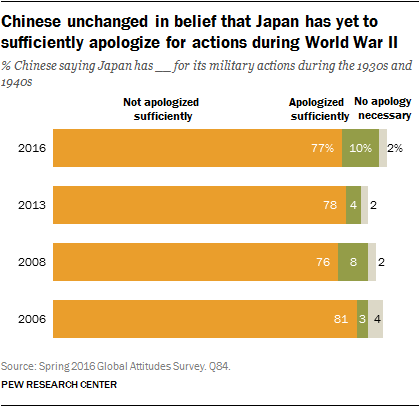

Japanese atonement for its activities in China before and during World War II is an ongoing source of friction in Sino-Japanese relations. The Japanese believe they have expressed regret for their behavior, while the Chinese disagree.

Japanese atonement for its activities in China before and during World War II is an ongoing source of friction in Sino-Japanese relations. The Japanese believe they have expressed regret for their behavior, while the Chinese disagree.

Among the Japanese people, 53% say they have apologized enough for their country’s military actions during the 1930s and 1940s. Such sentiment is up from 40% in 2006. Over that time period, the proportion of the public that believes Japan has not apologized sufficiently has fallen by 21 percentage points, from 44% to 23%. Notably, one-in-six Japanese (17%) say no apology is necessary.

The Chinese see Tokyo’s war-related penitence quite differently. Roughly three-quarters (77%) say Japan has not adequately expressed regret, and such Chinese sentiment is largely unchanged since 2006. Only 10% believe Tokyo has apologized enough.

Sino-Japanese frictions are not only an issue of historical concern. In East Asia such tensions remain an ever-present worry as Beijing and Tokyo engage in a prolonged dispute about who has sovereignty over the Senkaku or Diaoyu islands in the East China Sea.

Eight-in-ten Japanese are very (35%) or somewhat (45%) concerned that territorial disputes between China and neighboring countries could lead to a military conflict. Only 19% are not too concerned or not concerned at all. Notably, 42% of people ages 50 and older are very concerned, but just 28% of Japanese ages 18 to 34 are similarly concerned.

Eight-in-ten Japanese are very (35%) or somewhat (45%) concerned that territorial disputes between China and neighboring countries could lead to a military conflict. Only 19% are not too concerned or not concerned at all. Notably, 42% of people ages 50 and older are very concerned, but just 28% of Japanese ages 18 to 34 are similarly concerned.

The Chinese are somewhat less worried. Roughly six-in-ten are very concerned (18%) or somewhat concerned (41%). Notably, intense concern among the Japanese about a potential conflict is about twice that found among the Chinese. And twice as many Chinese as Japanese are not too concerned or not concerned at all.

Of course, territorial disputes between China and its neighboring countries involve more nations that just Japan. In a 2015 Pew Research Center survey, 91% of Filipinos and 83% of Vietnamese were worried that such disputes – which for these nations also involve China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea – could lead to a military conflict. In South Korea, 78% were similarly concerned about China’s territorial ambitions.