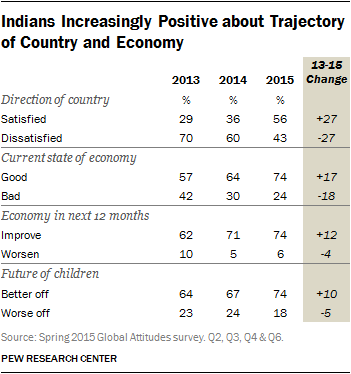

Public satisfaction with the way things are going in India has nearly doubled in less than two years. In 2013, just 29% of Indians were happy with the direction of their country. In 2015, 56% express satisfaction. And this approval of the overall trajectory of the nation is shared across party lines, generations and gender.

Public satisfaction with the way things are going in India has nearly doubled in less than two years. In 2013, just 29% of Indians were happy with the direction of their country. In 2015, 56% express satisfaction. And this approval of the overall trajectory of the nation is shared across party lines, generations and gender.

Part of this satisfaction with the way things are going can be attributed to the performance of the Indian economy. In the fourth quarter of 2013, around the time of Pew Research Center survey work there, India was growing at a seasonally adjusted rate of 7.1%. In the first quarter of 2015 it grew at 7.5%.

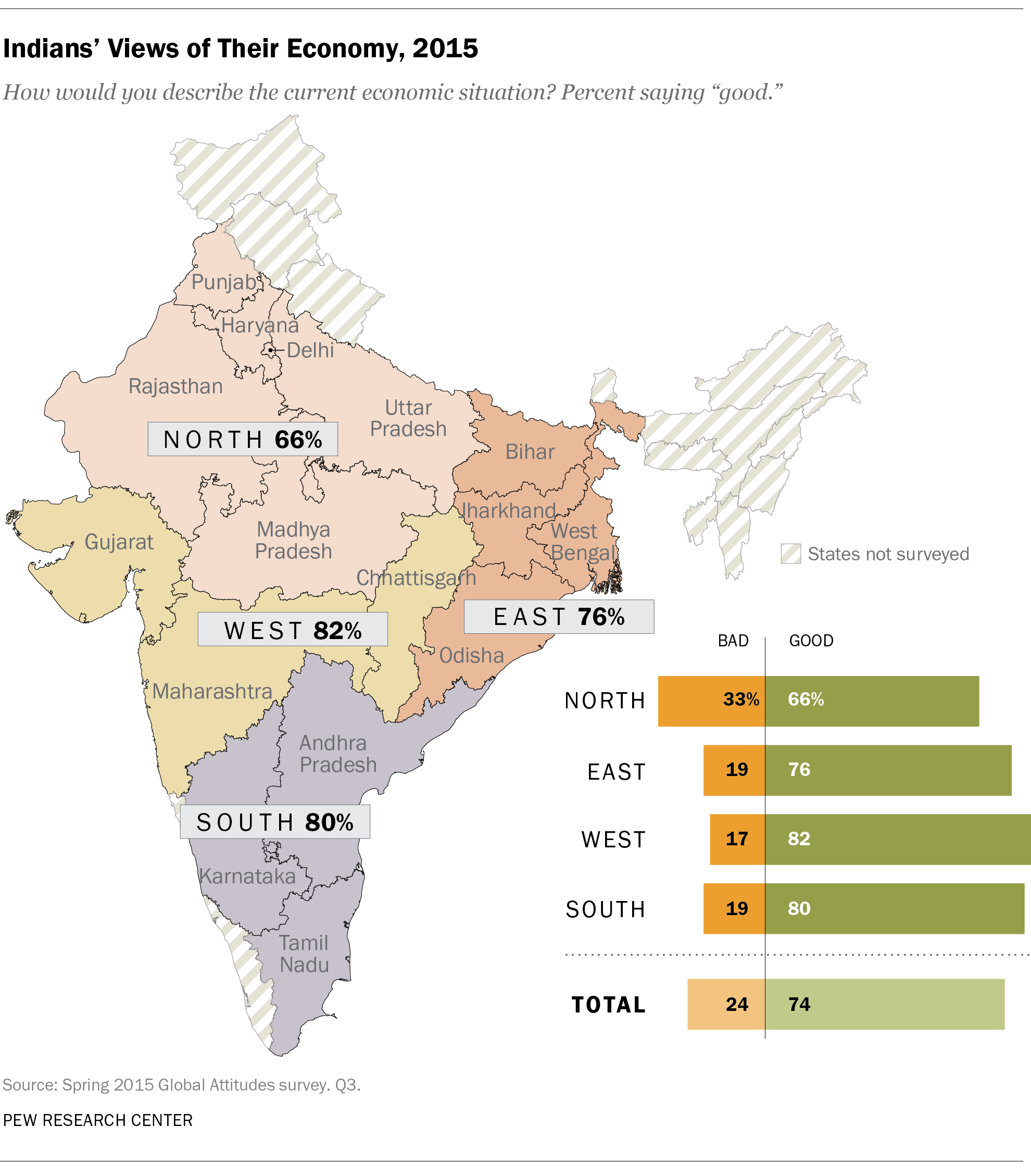

This persistence in relatively good economic performance has translated into a growing sense of satisfaction with economic conditions. In 2013, 57% of Indians thought their economy was in good shape. In 2015, 74% describe economic conditions as good, including 27% who say they are very good (up from 10% who were that enthusiastic less than two years ago).

Within India there are regional differences in economic perceptions. Roughly eight-in-ten Indians (82%) living in the western part of the country – the states of Chhattisgarh, Gujarat and Maharashtra – believe economic conditions are good. Just 66% of those living in the north – the states of Delhi, Haryana, Madhya Pradesh, Punjab, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh – agree.

Nearly three-quarters (74%) of the Indian public believes that India’s economic situation will improve over the next 12 months. This is an improvement from the 62% who were optimistic less than two years ago. The International Monetary Fund does not foresee much of an improvement in the Indian economy over the next year, but nor does it anticipate any significant slowdown.

Moreover, Indians’ expectations for the next generation have risen. In 2013, 64% thought that when Indian children grew up they would be better off financially than their parents. In 2015, 74% voice such optimism. Notably, 88% of those living in the south – the states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu – see a bright future for today’s children. But only 68% of people living in the eastern states of Bihar, Jharkhand, Odisha and West Bengal are as hopeful. Indians with at least some college education (83%) are more likely than those with a primary school education or less (70%) to be hopeful for the next generation.

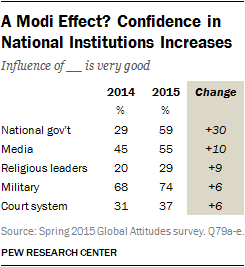

As the economy has picked up and the Modi administration has settled in, public satisfaction with a range of national institutions has improved. This is particularly the case with public perception of the national government.

As the economy has picked up and the Modi administration has settled in, public satisfaction with a range of national institutions has improved. This is particularly the case with public perception of the national government.

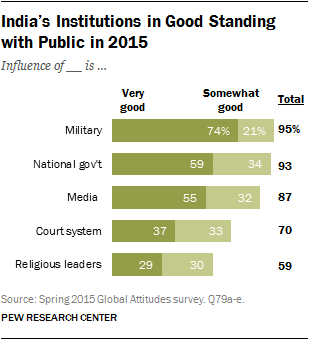

More than nine-in-ten Indians (93%) now say the central government is a good influence on the way things are going in the country. This approval is up from 70% in 2014. Even more notable, the proportion most satisfied is up 30 percentage points, from 29% who then said the national government in New Delhi was a very good influence to 59% who now hold this view.

More than nine-in-ten Indians (93%) now say the central government is a good influence on the way things are going in the country. This approval is up from 70% in 2014. Even more notable, the proportion most satisfied is up 30 percentage points, from 29% who then said the national government in New Delhi was a very good influence to 59% who now hold this view.

Not surprisingly, since their party now runs the central administration, about two-thirds (66%) of BJP adherents believe the national government is having a very good influence. In contrast, just 50% of Congress supporters give the national government high marks, and only 43% of AAP backers agree.

Public support for the military – 95% say it is a good influence – is high, including 74% who say the armed forces are having a very good influence on the nation.

Indian television, radio, newspapers and magazines also enjoy a great deal of public support: 87% believe they have a good impact on the way things are going in the country. However, just 55% say the media’s influence is very good, comparable to the intensity of backing for the government but far less than that for the military.

Seven-in-ten Indians give high marks to the court system. But only 37% say it is having a very good influence. There is a partisan difference in such sentiment: 38% of BJP supporters rate the courts highly, but only 23% of AAP followers agree.

Religious leaders are the least respected of the five institutions tested in the survey. Nearly six-in-ten Indians (59%) believe these leaders have a positive effect on the nation, but only 29% say they are a very good influence. Here again there is a sharp partisan difference of opinion. Supporters of the Hindu nationalist BJP (62%) are more likely to laud the influence of religious leaders; 53% of Congress party backers follow suit. But only 34% of AAP supporters see religious figures in that positive of a light. Urban dwellers (67%) are also more likely than those in rural areas (57%) to attribute an affirmative influence to religious leaders.

Despite widespread satisfaction with their economy, their institutions and Modi, Indians nonetheless believe they face a range of very serious problems. And, in some cases, their concern is on the rise.

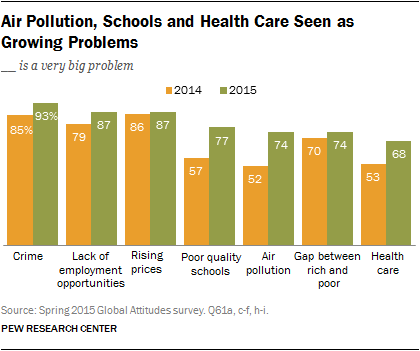

Indians are most concerned about crime among a list of 13 national challenges. More than nine-in-ten (93%) say crime is a very big problem. Such concern is up 8 percentage points since 2014.

Indians are most concerned about crime among a list of 13 national challenges. More than nine-in-ten (93%) say crime is a very big problem. Such concern is up 8 percentage points since 2014.

Indians are also very concerned about economic issues: a lack of employment opportunities, rising prices and, to a lesser extent, the gap between the rich and the poor. Fully 87% say joblessness is a very big problem facing India, an 8-point rise in such concern since 2014, but roughly comparable to unease about jobs in 2013. The same percentage (87%) complains about inflation. This proportion is largely unchanged since 2013. Inequality (74%) is seen as slightly less of a problem. Such concern is up a bit from 2014 but down 8 points since 2013.

Criticism of corrupt officials rivals concern about economic conditions: 86% say it is a very big problem. Such sentiment is comparable to what it was in 2013. Notably, Indians are slightly less concerned about corrupt business people. Roughly three-quarters (74%) say they are a very big problem for the country. And such concern is down 9 points from 2013.

Concern about terrorism (85%) is similar to Indians’ worries about economic issues and about government corruption.

Roughly three-in-four (77%) Indians say poor-quality schools are a very big national problem. And such concern is up 20 percentage points in the past year.

There has also been a 22-point increase in worry about air pollution: 74% say it is a very big problem, up from 52% who said the same a year ago. This jump in concern may reflect growing evidence of the poor air quality in Indian urban areas. A 2014 World Health Organization study found that India was home to 13 of the 20 cities around the world with the most-polluted air.

Nevertheless, anxiety about air pollution is a sentiment shared nationwide: Urban and rural Indians are equally concerned. However, BJP (77%) supporters are far more worried about air quality than AAP backers (57%).

Roughly seven-in-ten Indians (72%) believe that access to clean toilets is a major national problem. India accounts for about six-in-ten of the people around the world without toilets. And the World Bank estimates that lack of access to such sanitation facilities costs the Indian economy $54 billion a year thanks to the diarrhea and cholera spread by human excrement that pollutes groundwater, crops and waterways.

Roughly two-thirds of Indians (68%) think health care is a very big problem. Medical care spending in India as a percentage of the gross domestic product is less than half of the OECD average. The number of doctors per 1,000 Indians is less than a quarter the ratio in richer countries, and the ratio of nurses is one-eighth of the OECD average. BJP and Congress adherents (both 70%) are far more worried about health care than are AAP supporters (50%). Notably, people living in southern states (86%) are far more likely to say health care is a grave concern than are people living in western states (43%).

About two-thirds (68%) of Indian respondents see as a very big problem the situation in Kashmir, where India and Pakistan have long had competing territorial claims.

And just 59% mention communal relations as a major national challenge. Congress (61%) and BJP (60%) supporters are much more likely than AAP (40%) followers to complain about communal tensions. Indians living in western states (45%) are far less likely to say this is a very big problem than are those who live in the east (65%), south (61%) or north (60%).