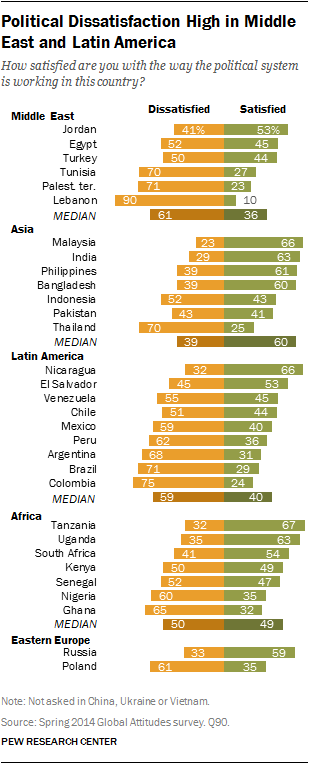

People in emerging and developing countries around the world are on balance unhappy with the way their political systems are working. A recent Pew Research Center survey finds that, across 31 emerging and developing nations, a median of 52% are dissatisfied with their political system, while 44% are satisfied. Discontent is particularly widespread in the Middle East and Latin America, where about six-in-ten say their system is not working well. The opposite is true, however, in Asia – a median of 60% are either very or somewhat satisfied with their political system.

People in emerging and developing countries around the world are on balance unhappy with the way their political systems are working. A recent Pew Research Center survey finds that, across 31 emerging and developing nations, a median of 52% are dissatisfied with their political system, while 44% are satisfied. Discontent is particularly widespread in the Middle East and Latin America, where about six-in-ten say their system is not working well. The opposite is true, however, in Asia – a median of 60% are either very or somewhat satisfied with their political system.

Political satisfaction is closely tied to views about national economic conditions. Countries where people say the economy is doing poorly are more likely to be unhappy with their current political system. And most people believe that the wealthy have too much influence on politics, while the poor have too little influence. These are among the key findings of a Pew Research Center survey, conducted in 34 countries among 38,620 respondents from March 17 to June 5, 2014.

Political Dissatisfaction

Half or more of those surveyed in 19 of 31 countries express disappointment in their political system. Middle Easterners (a median of 61%) and Latin Americans (59%) voice the greatest displeasure. In Lebanon, this frustration is particularly high – 90% say they are dissatisfied with the way the system works, a view shared by about seven-in-ten Palestinians and Tunisians. In Latin America, discontent is especially strong in Colombia and Brazil. Within the region, satisfaction with the political system is most common in Nicaragua and El Salvador, the two Central American countries surveyed.

Among those surveyed, Asians stand out as the happiest with their political system. Six-in-ten or more in four Asian countries approve of their system. With about two-thirds (66%) reporting satisfaction, Malaysians are the most positive, though Indians (63%), Filipinos (61%) and Bangladeshis (60%) hold similar views. Only in Thailand (70%), which in the past year has been ravaged by political turmoil, including a coup d’état, do a majority say they are dissatisfied.

In sub-Saharan Africa, people are split nearly equally on this question – a median of 50% are dissatisfied and 49% are satisfied. Dissatisfaction is highest in the West African nations of Ghana (65%) and Nigeria (60%). Tanzanians and Ugandans are among the happiest with their political system – more than six-in-ten in both countries believe it working well.

Political satisfaction is frequently related to economic attitudes. Countries where the economic mood is negative also have high levels of unhappiness with the political system. For instance, in Tunisia, a country where economic issues helped spark the 2010-2011 Jasmine Revolution, 88% say the economic conditions are poor, and 70% are dissatisfied with the current political system. Overall, the correlation between the percentage of people describing a country’s economic situation as bad and the percentage saying they are dissatisfied with the political system is 0.8, where 1 indicates a perfect relationship.

In every country surveyed, people who describe the current economic situation as bad are especially likely to express dissatisfaction with their political system. Differences are particularly stark in Venezuela, where 71% of those who rate the economy negatively are unhappy with the political system, compared with 17% of those who say the economy is doing well. People who believe inequality is a very big problem are also more likely to express disappointment in their political system in 12 of the 31 countries polled.

High-Income People Have Too Much Political Power

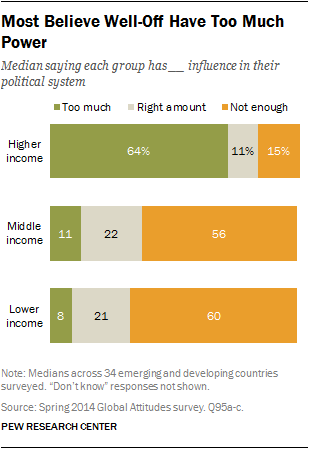

In addition to being dissatisfied with their political system, a median of 64% across the 34 emerging and developing nations surveyed say that higher-income people have too much influence in their political system. Just 15% say that those with high incomes do not have enough political power, and 11% say they have the right amount. In contrast, most think middle- and lower-income people have too little influence on politics. A median of 56% say that middle-income people do not have enough power, while 60% say this about those with lower incomes.

In addition to being dissatisfied with their political system, a median of 64% across the 34 emerging and developing nations surveyed say that higher-income people have too much influence in their political system. Just 15% say that those with high incomes do not have enough political power, and 11% say they have the right amount. In contrast, most think middle- and lower-income people have too little influence on politics. A median of 56% say that middle-income people do not have enough power, while 60% say this about those with lower incomes.

In 29 of 34 countries, more than half say too much political influence rests in the hands of society’s wealthiest people. This is especially true in Latin America, where a median of 74% say those with higher incomes have too much influence. Colombians, Peruvians and Brazilians are among the most ardent believers – about eight-in-ten in each country say that the rich have too much sway. Venezuela, which is still led by an acolyte of Hugo Chavez, is the only country in the region where less than half (44%) say the wealthy have too much influence. Those on the ideological right in Venezuela are somewhat more likely to believe that the well-off should have more political sway.

In 29 of 34 countries, more than half say too much political influence rests in the hands of society’s wealthiest people. This is especially true in Latin America, where a median of 74% say those with higher incomes have too much influence. Colombians, Peruvians and Brazilians are among the most ardent believers – about eight-in-ten in each country say that the rich have too much sway. Venezuela, which is still led by an acolyte of Hugo Chavez, is the only country in the region where less than half (44%) say the wealthy have too much influence. Those on the ideological right in Venezuela are somewhat more likely to believe that the well-off should have more political sway.

Sub-Saharan Africans (a median of 68%), Middle Easterners (61%) and Asians (57%) also report that those in the upper echelons of society have too much political influence. There are only two countries in the survey where fewer than four-in-ten believe the wealthy wield too much power – China (38%) and Vietnam (37%), two nations still ruled by officially Communist parties. Roughly a quarter in both countries believe the rich should have more influence on their political system than they currently do.