Six years after the beginning of the Great Recession, amid an uneven global economic recovery, publics around the world remain glum. In most nations, people say their country is heading in the wrong direction and most voice the view that economic conditions are bad, according to a new 44 country survey by the Pew Research Center conducted among 48,643 respondents from March 17 to June 5, 2014.

Six years after the beginning of the Great Recession, amid an uneven global economic recovery, publics around the world remain glum. In most nations, people say their country is heading in the wrong direction and most voice the view that economic conditions are bad, according to a new 44 country survey by the Pew Research Center conducted among 48,643 respondents from March 17 to June 5, 2014.

This is the first in a series of Pew Research Center reports based on the Spring 2014 global survey that will look at public views of major economic changes in advanced, emerging and developing nations.

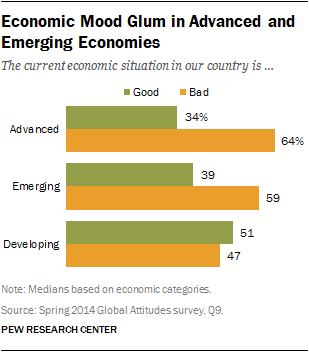

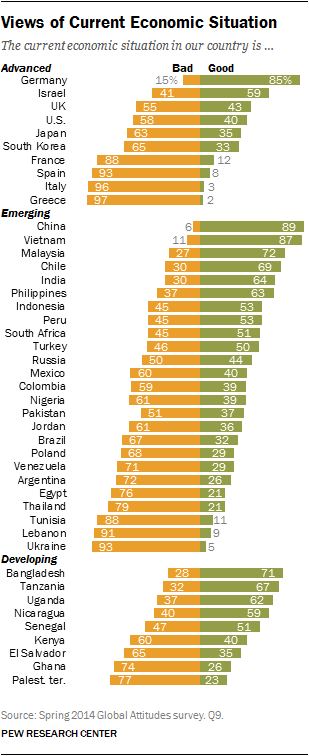

A global median of 60% see their country’s economy performing poorly. This includes 64% of those surveyed in advanced economies and 59% in emerging markets.1 Only in developing economies is there some semblance of satisfaction with economic performance: 51% voice the view that their economy is doing well.

Those who see their economy in the most negative light are the Greeks (97% say economic conditions are bad), Italians (96%), Spanish (93%) and Ukrainians (93%). In the United States, 58% are of the opinion that the American economy is not doing well; only 40% say its performance is good. (For more on the U.S. economy, see Views of Job Market Tick Up, No Rise in Economic Optimism.)

Those most positive about their national economic conditions are the Chinese (89%), Vietnamese (87%) and Germans (85%).

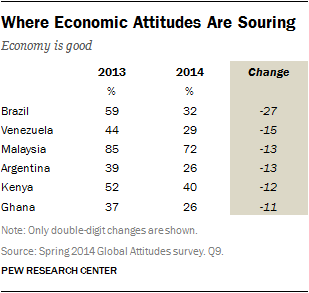

In a half dozen countries, economic attitudes have soured in the last year. In 2013, a majority of Brazilians (59%) said their economy was doing well. Today only 32% hold this view, a 27 percentage point drop in economic confidence. There has also been a 15 point decline in positive views of the economy in Venezuela and 13 point drop-offs in Argentina and Malaysia.

In a half dozen countries, economic attitudes have soured in the last year. In 2013, a majority of Brazilians (59%) said their economy was doing well. Today only 32% hold this view, a 27 percentage point drop in economic confidence. There has also been a 15 point decline in positive views of the economy in Venezuela and 13 point drop-offs in Argentina and Malaysia.

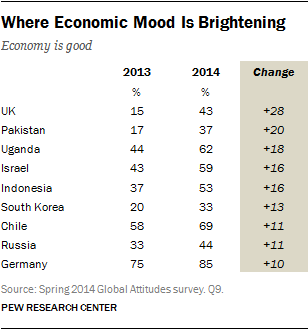

However, over the last year, the economic mood has brightened in a number of nations. In 2013 in the United Kingdom and Pakistan, only 15% and 17% of the public, respectively, thought the economy was doing well. British assessments of their economic conditions are now up 28 points. Pakistanis’ economic frame of mind has improved by 20 points. Double digit improvements in economic mood are also found in Uganda, Israel, Indonesia, South Korea, Russia, Chile and Germany.

However, over the last year, the economic mood has brightened in a number of nations. In 2013 in the United Kingdom and Pakistan, only 15% and 17% of the public, respectively, thought the economy was doing well. British assessments of their economic conditions are now up 28 points. Pakistanis’ economic frame of mind has improved by 20 points. Double digit improvements in economic mood are also found in Uganda, Israel, Indonesia, South Korea, Russia, Chile and Germany.

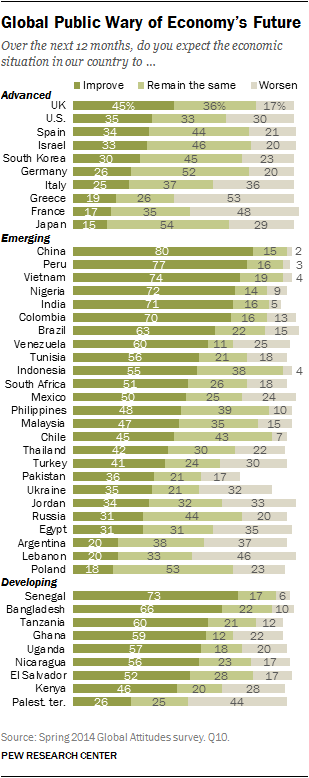

Expectations for the future of national economies are a bit more positive overall. A global median of 46% sees their economy picking up over the next year. This includes 45% in the UK — a 23 point rise in public economic optimism about the future since 2013. A majority of Indonesians (55%) and Ugandans (57%) also expect their economy to perform better over the next year, with such confidence up 18 points and 15 points, respectively, since last year.

At the same time, optimism about the economy over the next 12 months has nosedived in Japan, where just 15% foresee their economy improving, down from 40% who were hopeful a year ago. More than six-in-ten Malaysians (64%) were upbeat about their economic prospects in 2013; now, less than half (47%) see a brighter economic future. Notably, U.S. optimism about the trajectory of the economy is down nine points, from 44% in 2013 to 35% in 2014.

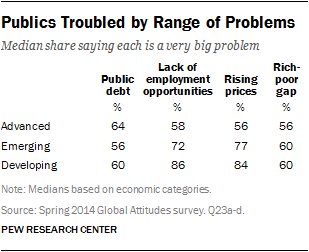

Concern about the economy manifests itself in widespread and overwhelming worry about a range of economic challenges. A global median of 77% says both rising prices and a lack of employment opportunities are very big problems in their country. A median of 60% holds the view that the gap between the rich and the poor is a very big concern. And 59% assert that public debt is similarly a very big challenge.

Concern about the economy manifests itself in widespread and overwhelming worry about a range of economic challenges. A global median of 77% says both rising prices and a lack of employment opportunities are very big problems in their country. A median of 60% holds the view that the gap between the rich and the poor is a very big concern. And 59% assert that public debt is similarly a very big challenge.

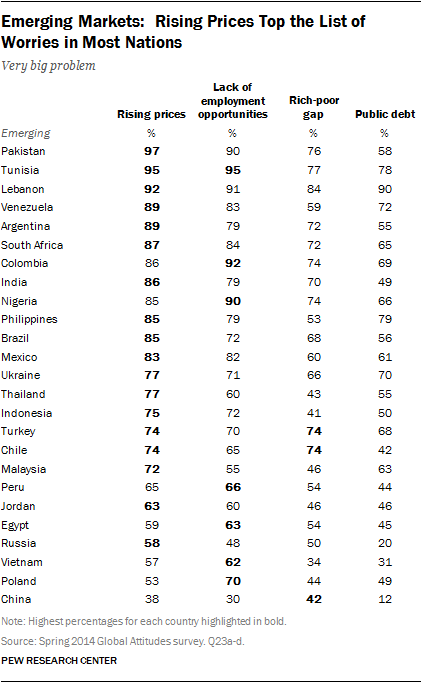

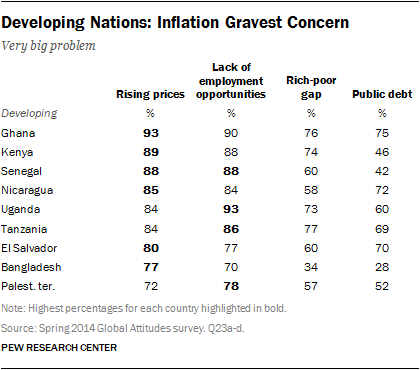

In advanced economies, the greatest concern is about debt, with a median of 64% saying public debt is a major worry. In emerging markets, inflation (77%) is seen to be the gravest challenge, followed by a lack of employment opportunities (72%). And in developing societies, both jobs (86%) and inflation (84%) are the subject of intense public worry.

1. National Conditions Not Good

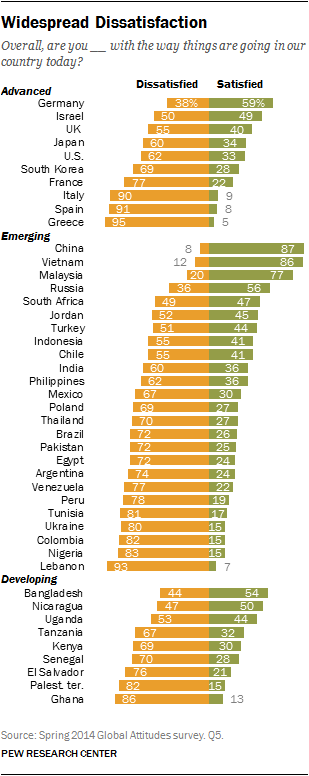

Most national publics around the world – a global median of 69% – are dissatisfied with the way things are going in their country. By this broad measure of national unease, which may encompass public perception of economic, political, social and security conditions, half or more of the publics in 36 of the 44 nations surveyed say conditions in their society are not good.

Most national publics around the world – a global median of 69% – are dissatisfied with the way things are going in their country. By this broad measure of national unease, which may encompass public perception of economic, political, social and security conditions, half or more of the publics in 36 of the 44 nations surveyed say conditions in their society are not good.

This displeasure is shared across advanced economies (a median of 66% unhappy), emerging markets (69%) and developing economies (69%). Regionally, the greatest unease is in Europe (77%), Latin America (74%) and the Middle East (72%). The least dissatisfaction is in Asia (60%). But it is hardly a sign of well-being that six-in-ten Asians are discontented with the way things are going.

At a national level, the most dissatisfied are the Greeks (95%), the Lebanese (93%), the Spanish (91%) and the Italians (90%). About six-in-ten Americans (62%) are also unhappy with the way things are going in the U.S. The most content with their country’s direction are the Chinese (87%), the Vietnamese (86%) and the Malaysians (77%).

Notably, Russian satisfaction with their nation’s direction has improved 19 percentage points, from 37% to 56%, in the last year, possibly a byproduct of public backing for Russia’s newly assertive foreign policy. British contentment has grown 14 points, from 26% to 40%, likely the consequence of the pickup in the economy.

2. Widespread Economic Gloom

The global public is generally downbeat about the economic situation in their countries, except in Asia.

The global public is generally downbeat about the economic situation in their countries, except in Asia.

Their mood reflects recent economic conditions. Global growth slowed in the first quarter of 2014, immediately prior to the survey. At 2.75%, it was down a full percentage point from the growth experienced in the second half of 2013, according to the International Monetary Fund. Some nations, especially advanced economies, such as Japan, Germany, Spain, and the UK, performed better than expected. But their success was outweighed by disappointing growth in China and the U.S. And weak demand in those economies sapped economic growth in emerging markets, where success is often driven by exports to the U.S. and China.

In advanced economies, a median of just 34% say their economy is in good shape, and only 39% in emerging economies share similar positive views. In developing economies, publics are divided: 51% say their economy is doing well and 47% see it performing poorly. These views are relatively unchanged in the emerging markets that were surveyed in both 2013 and 2014. But in the 10 advanced economies surveyed in both years, the median who hold the view that their economy is good has actually improved by 16 percentage points, a sign that even the modest economic recovery experienced in parts of Europe, Japan and the U.S. is resonating with the public.

Seen through a regional lens, a median of 88% of Europeans say their economies are doing poorly, as do 76% in the Middle East and 60% in Latin America. Africans are divided: 51% express the view that their economies are doing well, 47% say their performance is bad. Asians, however, are generally upbeat: 63% say their economies are in good shape, just 37% see them performing poorly.

The Chinese (89%), Vietnamese (87%) and Germans (85%) feel the best about their country’s economic situation. And they have reason to feel positive. China’s economy is expected to grow by 7.4% this year and Vietnam’s by 5.6%, according to the IMF. The Greeks (2%) and Italians (3%) are the most downbeat about current economic conditions. Again, this is hardly surprising. Italy fell back into recession in the first half of 2014 and Greece’s economy continued to shrink.

3. Mixed Views on Next 12 Months

The IMF expects the world economy to pick up a bit, growing at 3.4% in 2014, slightly faster than in 2013, and expand by 4% in 2015.

The IMF expects the world economy to pick up a bit, growing at 3.4% in 2014, slightly faster than in 2013, and expand by 4% in 2015.

However, the public, wary about the prospect of such growth, is split down the middle between expectations of improvement and the assumption that things will stay the same or will worsen. A median of 46% across the 44 countries surveyed expect their economy to improve. An equal proportion of people say it will remain the same (26%) or worsen (20%).

A median of 57% of those in developing economies hold the view that the economy is likely to improve. Just 17% say it will worsen. A plurality (48%) in emerging markets expect economic conditions to be better, while only 18% see them worsening. And a plurality (41%) in advanced economies anticipate that the economic situation in their country will remain the same, with the rest of the public evenly divided between those who say it will improve and those who fear it will deteriorate.

Regionally, people in Africa (59%) and Latin America (56%) are the most hopeful about the coming year. Nearly half (48%) of Asians agree. But only 25% of Europeans expect economic conditions to improve.

The most optimistic nation is China (80%), where the IMF expects growth to be 7.1% in 2015. But there are also high expectations in the Latin American nations of Peru (77%) and Colombia (70%), where the IMF foresees growth of 5.8% and 4.5% respectively. The same is true in the Asian economies of Vietnam (74%) and India (71%), where the IMF forecasts growth of 5.7% and 6.4% respectively; and in the African countries Senegal (73%) and Nigeria (72%), where the IMF expects growth of 4.8% and 7.0%.

The greatest pessimists can be found in Greece (53% worsen), France (48%), Lebanon (46%) and the Palestinian territories (44%).

Americans are almost evenly divided: 35% are hopeful of improvement, 33% expect more of the same and 30% see conditions worsening. But there is a partisan divide in views on the trajectory of the economy: 54% of Democrats expect economic conditions to improve, while 48% of Republicans anticipate that they will .

4. Multiple Economic Problems

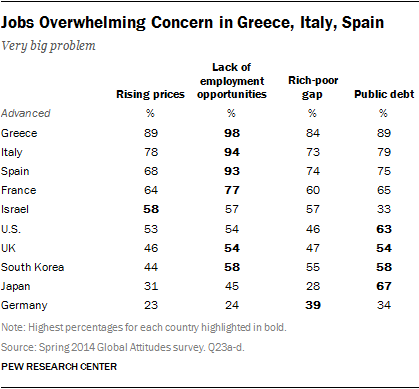

Publics concerned about the economy generally see problems wherever they look, and their anxiety is often quite intense. Across a range of economic problems, including inflation, unemployment, income inequality and public debt, strong majorities in most countries not only see each as a concern, they voice the view that these are very big problems facing their country.

In six of the 10 advanced economies surveyed, the lack of employment opportunities is considered the top economic challenge. Almost every Greek (98%) in the survey says joblessness is a major issue. This finding is hardly surprising in a country where the official unemployment rate for 2013 was 27%. More than nine-in-ten Italians and Spanish agree that the lack of employment opportunities in their own nations is a top problem. The least troubled about unemployment are the Germans (24%), where the joblessness rate was 5.2% in 2013.

In six of the 10 advanced economies surveyed, the lack of employment opportunities is considered the top economic challenge. Almost every Greek (98%) in the survey says joblessness is a major issue. This finding is hardly surprising in a country where the official unemployment rate for 2013 was 27%. More than nine-in-ten Italians and Spanish agree that the lack of employment opportunities in their own nations is a top problem. The least troubled about unemployment are the Germans (24%), where the joblessness rate was 5.2% in 2013.

Public debt is the major worry in Japan (67%) and the U.S. (63%), where indebtedness is equal to 243.5% and 105.7% of the GDP respectively. But the greatest concern is in Greece (89%), Italy (79%) and Spain (75%). The Israelis (33%) are the least concerned.

The Germans (23%) are the least anxious about inflation, possibly because Germany has recently been experiencing its lowest inflation in years.

And only in Germany (39%) is the gap between the rich and the poor viewed as the principal economic problem facing the country. The greatest worry about inequality is again in Greece

In 18 of 25 emerging markets rising prices are among the gravest economic concerns. Nearly all Pakistanis (97%) complain that inflation is a very big problem, as do 95% of Tunisians and 92% of Lebanese. The least concerned about inflation are the Chinese (38%).

In 18 of 25 emerging markets rising prices are among the gravest economic concerns. Nearly all Pakistanis (97%) complain that inflation is a very big problem, as do 95% of Tunisians and 92% of Lebanese. The least concerned about inflation are the Chinese (38%).

In seven emerging economies joblessness is seen as among the most important economic problems, with the greatest concern in Tunisia (95%), Colombia (92%) and Nigeria (90%). The Chinese are again the least worried (30%).

Notably, Turks (74%), and Chileans (74%) cite income inequality as among the leading economic challenges facing their country. But the greatest concern about the gap between the rich and the poor is in Lebanon (84%). In emerging markets, the least concern about inequality is found in Vietnam (34%).

Nowhere in the emerging markets surveyed is public debt seen as the most important economic challenge facing the nation. Nevertheless, it is considered a major problem in Lebanon (90%), the Philippines (79%) and Tunisia (78%). Only 12% of the Chinese see such debt as a very important issue.

Rising prices are viewed as the most pressing economic challenge in six of nine developing countries. Inflation most troubles the public in Ghana (93%), Kenya (89%) and Senegal (88%). Joblessness is seen as a very big problem in Uganda (93%) in particular. Both unemployment and inflation are judged major problems by at least seven-in-ten in all developing countries surveyed.

Rising prices are viewed as the most pressing economic challenge in six of nine developing countries. Inflation most troubles the public in Ghana (93%), Kenya (89%) and Senegal (88%). Joblessness is seen as a very big problem in Uganda (93%) in particular. Both unemployment and inflation are judged major problems by at least seven-in-ten in all developing countries surveyed.

Income inequality is a particular worry in Tanzania (77%) and Ghana (76%), but a relatively low concern in Bangladesh (34%).

Public debt especially worries Ghanaians (75%) and Nicaraguans (72%). It is again the least of Bangladeshi economic anxieties.

Despite their high level of distress about various economic problems, public views of these challenges have not changed much since 2013 except in a few societies.

The greatest movement in public economic concerns involves declining worry about public debt. The proportion of the public that sees this as a major problem is down 33 points in Senegal, 24 points in Pakistan, 20 points in the Palestinian territories, 19 points in Russia, 16 points in Chile, 15 points in Brazil and 13 points in Israel, Indonesia and Kenya.

The perception that joblessness is a very big problem has gone down 15 percentage points in Chile and El Salvador since 2013, 13 points in Japan, 12 points in the UK and 11 points in South Korea. Intense concern about inflation is down 21 percentage points in China in the last year, 13 points in Poland, 12 points in Israel and South Korea and 10 points in Chile. Serious worry about the gap between the rich and the poor is down by double digits in a number of nations: by 18 points in Senegal, 12 points in Germany and India, 11 points in South Korea and 10 points in China and Poland.