As they continue to struggle with the effects of the Great Recession, publics in advanced economies are pessimistic about the financial prospects for the next generation. Most of those surveyed in richer nations think children in their country will be worse off financially than their parents. In contrast, emerging and developing nations are more optimistic that the next generation will have a higher standard of living.

As they continue to struggle with the effects of the Great Recession, publics in advanced economies are pessimistic about the financial prospects for the next generation. Most of those surveyed in richer nations think children in their country will be worse off financially than their parents. In contrast, emerging and developing nations are more optimistic that the next generation will have a higher standard of living.

Overall, optimism is linked with recent national economic performance. Countries that have enjoyed relatively high levels of growth in recent years also register some of the highest levels of confidence in their children’s economic futures.

Looking ahead, people in the emerging and developing world see better opportunities at home than abroad. Majorities or pluralities in 30 of the 34 emerging and developing nations surveyed say they would tell young people in their country to stay at home in order to lead a good life, instead of moving to another country.

Looking ahead, people in the emerging and developing world see better opportunities at home than abroad. Majorities or pluralities in 30 of the 34 emerging and developing nations surveyed say they would tell young people in their country to stay at home in order to lead a good life, instead of moving to another country.

A good education and hard work are most often seen as the keys to getting ahead in life. This view is especially prevalent in emerging and developing nations, where most see economic opportunity expanding. Still, many also believe success can be determined by things outside a person’s control, such as luck or having a wealthy family.

Despite the long-term optimism that exists in many countries, there are widespread concerns about inequality. Majorities in all of the 44 nations polled say the gap between rich and poor is a big problem facing their countries, and majorities in 28 nations identify this as a very big problem. More than seven-in-ten hold this view in Greece, Spain and Italy – countries that faced significant economic challenges during the last several years. But even in the emerging and developing nations that have enjoyed tremendous growth over the last couple of decades, there is a consensus that those at the top are reaping the gains while others are being left behind.1

Despite the long-term optimism that exists in many countries, there are widespread concerns about inequality. Majorities in all of the 44 nations polled say the gap between rich and poor is a big problem facing their countries, and majorities in 28 nations identify this as a very big problem. More than seven-in-ten hold this view in Greece, Spain and Italy – countries that faced significant economic challenges during the last several years. But even in the emerging and developing nations that have enjoyed tremendous growth over the last couple of decades, there is a consensus that those at the top are reaping the gains while others are being left behind.1

People blame inequality on a variety of causes, but they see their government’s economic policies as the top culprit. A global median of 29% say those policies are most to blame for the gap between rich and poor. Fewer people blame the amount of workers’ wages, the educational system, the fact that some work harder than others, trade, or the tax system.

The survey also asked what would do more to reduce inequality: low taxes on the wealthy and corporations to encourage investment and growth, or high taxes on the wealthy and corporations to fund programs that help the poor. The balance of opinion in emerging and developing nations is that low taxes are most effective while people in advanced economies tend to favor high taxes.

While inequality is considered a major challenge by a median of 60% across the 44 nations polled, higher numbers say rising prices and a lack of job opportunities (medians of 77%) are very big problems. And people in advanced, emerging and developing markets alike are clearly willing to live with some degree of inequality as part of a free market system. Majorities or pluralities in 38 of 44 countries say that most people are better off in a free market economy, even though some people are rich while others are poor.

These are among the key findings of a survey by the Pew Research Center, conducted in 44 countries among 48,643 respondents from March 17 to June 5, 2014. While this report focuses largely on differences and similarities between economically advanced, emerging and developing nations, the survey also finds significant differences by region.

These are among the key findings of a survey by the Pew Research Center, conducted in 44 countries among 48,643 respondents from March 17 to June 5, 2014. While this report focuses largely on differences and similarities between economically advanced, emerging and developing nations, the survey also finds significant differences by region.

For instance, Asians are particularly optimistic about the next generation’s financial prospects. Fully 94% of Vietnamese, 85% of Chinese, 71% of Bangladeshis, and 67% of Indians think today’s children will be better off than their parents. Africans and Latin Americans are also on balance optimistic, while Middle Easterners tend to be pessimistic. And in Europe and the United States, pessimism is pervasive.

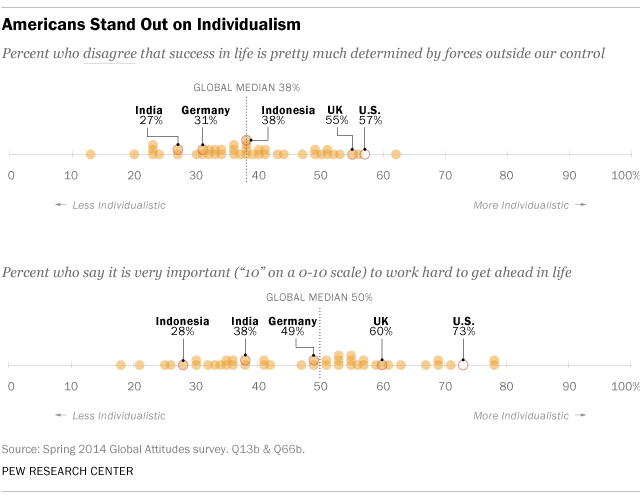

The survey also highlights how Americans are different from many others around the world on questions related to individualism, a value often associated with American exceptionalism. Fifty-seven percent of Americans disagree with the statement “Success in life is pretty much determined by forces outside our control,” a considerably higher percentage than the global median of 38%. Similarly, Americans place an especially strong emphasis on the value of hard work – 73% think it is very important to work hard in order to get ahead in life, compared with a global median of 50%.

Emerging and Developing Economies See Brighter Future

People in emerging and developing nations are more optimistic for the next generation than publics in advanced economies. Still, there is a wide range of attitudes within each group.

People in emerging and developing nations are more optimistic for the next generation than publics in advanced economies. Still, there is a wide range of attitudes within each group.

About half or more in 16 of the 25 emerging markets surveyed say children in their nation will be better off financially than their parents, including at least seven-in-ten in Vietnam, China, Chile and Brazil. People in Middle Eastern emerging economies, however, are much more skeptical. In Jordan, Turkey, Egypt and Lebanon, roughly a third or fewer say the nation’s children will be better off financially than their parents. Poles are also considerably pessimistic about the next generation’s opportunities, an outlook which may be influenced by the economic crisis in the European Union.

Developing economies are divided on this question. Roughly half or more in Bangladesh, Nicaragua, Senegal, Ghana and Uganda say their children will be more successful than the older generation. Fewer than four-in-ten agree in Tanzania, Kenya, El Salvador and the Palestinian territories.

Publics in advanced economies are the most pessimistic. In most of the high income countries surveyed, three-in-ten or fewer say the nation’s children will surpass their parents financially. Majorities in eight of the 10 countries believe the younger generation will be worse off. The French, Japanese and British are particularly downbeat about the future. Nearly two-thirds of Americans say the same.

In general, countries that have experienced higher economic growth since 2008 are more optimistic for the next generation than publics that have had less growth. For example, in China, which has experienced an average GDP growth of 9% between 2008 and 2013, 85% of the public says young people will be better off financially than their parents. Meanwhile, Italians, who have seen their economy contract by an average of 2% per year over the course of the global recession, are much less optimistic (15%).

In some countries, optimism for the next generation has changed significantly in just the past year and these shifts in attitudes appear to be related in part to changing views about the country’s economy. Today, 51% of Ugandans say children will be better off financially than their parents, compared with 39% last year. Over the same time period, Ugandans also became significantly more positive about the current economy (+18 percentage points). Optimism for young people improved since 2013 as well in Senegal (+12), South Africa (+11), Germany (+10), Pakistan (+8), Egypt (+7) and the UK (+6). At the opposite end, hope for the nation’s youth in Venezuela declined by 18 points in the past year as positive ratings of the economy also fell by 15 points. Optimism about the children’s future also decreased over the past 12 months in Kenya (-19), Malaysia (-14), the Philippines (-11), El Salvador (-8) and .

Perhaps because most publics see a bright future for their nation’s youth, people in emerging and developing nations generally believe that it is better for young people who want to have a good life to stay in their home country, rather than move to another country.

Perhaps because most publics see a bright future for their nation’s youth, people in emerging and developing nations generally believe that it is better for young people who want to have a good life to stay in their home country, rather than move to another country.

Majorities or pluralities in 30 of the 34 emerging and developing nations surveyed say young people should stay at home to be successful, including more than eight-in-ten in Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, Malaysia and Tanzania.

In just seven countries do at least four-in-ten say the next generation has more opportunities abroad. This includes publics that have recently witnessed massive political and economic upheaval, such as the Egyptians, worsening ethnic conflict, such as the Lebanese, and severe gang violence, such as the Salvadorans. Poles are also more inclined than most publics to say that young people should move abroad to have a good life. This may reflect the open borders between Poland and other EU countries as well as dissatisfaction with economic conditions at home.

In some countries, young people, those ages 18-29, are more optimistic than people 50 and older about prospects for the next generation. The age gap is particularly large in Uganda (+22 percentage points children will be better off financially), the UK (+21), Nicaragua (+20), Spain (+19) and Thailand (+15). At the same time, in many countries, young people are also more likely to say there are more opportunities to have a good life abroad than at home. On this question, the biggest age gaps are in Tunisia (+25 percentage points recommend young people move to another country), Brazil (+19), the Palestinian territories (+16) and Chile (+15).

Success May Be Out of Our Control

Majorities or pluralities in 28 of the 44 countries surveyed agree that success in life is pretty much determined by forces outside our control. People in developing and emerging markets (medians of 56%) are somewhat more likely to believe their fate is out of their hands than those in advanced economies (51%).

Majorities or pluralities in 28 of the 44 countries surveyed agree that success in life is pretty much determined by forces outside our control. People in developing and emerging markets (medians of 56%) are somewhat more likely to believe their fate is out of their hands than those in advanced economies (51%).

In most developing economies, majorities say success is determined by outside forces, including 74% in Bangladesh and 67% in Ghana. Nicaraguans are the least likely to agree among developing countries.

Majorities in 15 of the 25 emerging markets surveyed also think their fate is out of their hands, including six-in-ten or more in Turkey, Vietnam, South Africa, Malaysia, Poland, Lebanon and Nigeria. Latin American countries are generally the least likely among emerging markets to agree their future is determined by outside forces, including fewer than four-in-ten in Colombia, Mexico and Venezuela.

Meanwhile, in advanced economies, roughly half or fewer in six of the 10 countries surveyed agree that success is out of our control. Americans are the least likely to say they are not the masters of their fate (40%), one of the lowest percentages among the 44 countries surveyed.

Education and Hard Work Seen as the Keys to Moving Up

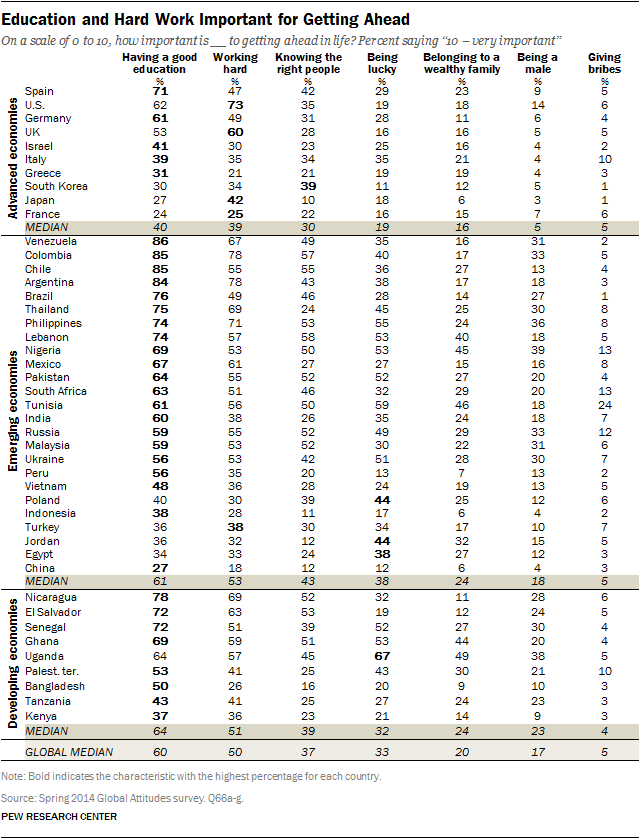

When asked to rate on a scale of 0 to 10 how important a range of characteristics are to getting ahead in life, most global publics say having a good education (global median of 60% rating this “10 – very important”) and working hard (50%) are very important. Knowing the right people (37%), being lucky (33%), coming from a wealthy family (20%), being born a male (17%) and giving bribes (5%) are seen as less essential to doing well.

In eight of the nine developing countries surveyed, having a good education tops the list of keys to success. About seven-in-ten or more in Nicaragua (78% rate as 10), El Salvador (72%), Senegal (72%) and Ghana (69%) say education is very important to advancing in life. Only in Uganda is luck seen as roughly equal to education in determining one’s future (67% luck vs. 64% education).

Similarly, the dominant opinion among emerging markets is that having a good education is very important to being successful, a view held by more than eight-in-ten Venezuelans (86% rate as 10), Colombians (85%), Chileans (85%) and Argentines (84%). Working hard is the second most common response in most countries. Poland, Jordan and Egypt are exceptions among the emerging markets – these publics say luck is at least as important, if not more so, as education or hard work for getting ahead in life.

Advanced economies are a bit more divided between education and hard work as the keys to success. Education is the top response among five of the 10 countries – Spain (71% rate as 10), Germany (61%), Israel (41%), Italy (39%) and Greece (31%) – and work ethic is the top in four – the U.S. (73%), UK (60%), Japan (42%) and France (25%). The percentage of Americans who say hard work is very important to getting ahead in life is among the highest across all 44 countries. South Koreans are the only public where knowing the right people is the most commonly cited key to success (rated at the top of the scale by 39%).

Even though few rank knowing the right people, being lucky, being from a wealthy family, or being male as a 10 on the 0-10 importance scale, many people do rate these items highly with a score of seven or more. For example, while a global median of just 33% rank being lucky at 10, 75% rate it at seven or higher. In general, emerging and developing publics are somewhat more likely than advanced economies to believe that all of these items are important for getting ahead.

Being a male does not top the list of keys to success, but there is a large gender gap on the question. In 32 of the 44 countries surveyed, men are significantly more likely than women to say gender is very important to getting ahead. The gender gap on this issue tends to be larger in the emerging and developing economies surveyed.

Inequality a Major Problem

A global median of 60% say that the gap between rich and poor is a very big problem in their country. Concern is somewhat higher among developing economies and emerging markets (median of 60% in each), but is also shared by people in advanced economies (56%).

A global median of 60% say that the gap between rich and poor is a very big problem in their country. Concern is somewhat higher among developing economies and emerging markets (median of 60% in each), but is also shared by people in advanced economies (56%).

Nonetheless, despite this high level of worry about inequality, the issue only ties or tops the list of economic problems in four of the 44 countries surveyed. In general, people in advanced economies tend to worry more about public debt and unemployment than inequality, while those in emerging markets and developing economies are more concerned about inflation and jobs. (For more on views about economic issues, see this September Pew Research report)

Publics Fault Government Policies

The top culprit for income inequality cited by publics around the world is their national government’s economic policies. A global median of 29% say their government’s policies are to blame for the gap between the rich and the poor, while the amount workers are paid is a close second at 23%. Globally, people place less blame on the educational system (11%), a lack of individual hard work (10%), trade between countries (8%) and the structure of the tax system (8%).

Advanced economies in particular lean toward the notion that their governments are to blame for inequality (median of 32%). The Greeks (54%), Spanish (52%) and South Koreans (46%) are government’s harshest critics. Significant percentages among advanced economies also fault workers’ wages for the gap between the rich and the poor, including 29% in Japan and 26% each in France and Germany. The Americans and British are two of the few publics to blame individuals’ lack of hard work (24%) about as much as they do their government’s policies (24% in U.S., 23% in UK).

Emerging markets are more divided. Pluralities in nine of the 25 countries surveyed blame their government for inequality in their country, including roughly four-in-ten or more in Ukraine (45%), India (45%), Lebanon (43%), China (43%), Tunisia (43%), Turkey (42%) and Nigeria (39%). Meanwhile, pluralities in another six countries say workers’ wages are the primary scapegoat. Latin American publics – such as Brazilians (44%), Chileans (39%) and Colombians (39%) – are particularly likely to blame inadequate take-home pay for the gap between the rich and poor.

People in developing economies are also split between blaming the government for income inequality in their country and faulting workers’ wages. Pluralities in Kenya (36%), Ghana (29%) and Tanzania (29%) say inequality is their government’s fault, while Salvadorans (32%) tend to blame the amount workers are paid. Nearly equal percentages in the Palestinian territories, Bangladesh, Senegal and Uganda say both the government and wages are the culprits. Nicaragua (31%) is the country with the highest percentage who say a lack of individual hard work is the problem.

Many Say Low Taxes Are the Answer

Pluralities or majorities in 22 of the 44 countries surveyed say to reduce inequality it is more effective to have low taxes on the wealthy and corporations to encourage investment and economic growth rather than high taxes on the wealthy and corporations to fund programs that help the poor. Publics in 13 countries prefer the high tax option.

Pluralities or majorities in 22 of the 44 countries surveyed say to reduce inequality it is more effective to have low taxes on the wealthy and corporations to encourage investment and economic growth rather than high taxes on the wealthy and corporations to fund programs that help the poor. Publics in 13 countries prefer the high tax option.

Overall, advanced economies (median of 48%) are somewhat more supportive than either developing (40%) or emerging (31%) countries of using high taxes on the wealthy and corporations to address income inequality. The broadest support comes from Germany, where 61% favor using high taxes to fund poverty programs. Roughly half or more in Spain (54%), South Korea (53%), the UK (50%) and the U.S. (49%) agree. In Italy (68%), France (61%) and Greece (50%), opinion leans toward low taxes to encourage investment.

In most advanced economies, people who say they are very concerned about inequality are particularly supportive of income redistribution to reduce the gap between the rich and poor. There is also a large ideological divide over taxes in Europe and the U.S. In general, individuals on the left are much more likely than those on the right to prefer high taxes on the wealthy and corporations. For example, 71% of those on the left in Spain support redistribution, compared with 45% of people on the right. In the U.S., 70% of liberals say high taxes are more effective to combat inequality while just 33% of conservatives agree.

The prevailing view in most emerging markets surveyed is that low taxes on the rich and businesses to stimulate growth are a better way to address inequality. Roughly six-in-ten or more express this opinion in Brazil (77%), Argentina (60%), Vietnam (60%) and the Philippines (59%). In just five of the 25 emerging countries do pluralities or majorities pick high taxes as the preferred means of reducing the gap between the rich and poor, including 57% in Jordan, 53% each in Egypt and Chile, 48% in Ukraine and 42% in China.

Developing economies also lean more toward low taxes on the wealthy and corporations to encourage investment rather than high taxes for redistribution. At least half prefer low taxes in Uganda (64%), Ghana (57%), Kenya (52%) and Nicaragua (52%). El Salvador is the only developing economy where a majority (58%) chooses high taxes.

Free Market Seen as Best, Despite Inequality

Despite the fact that most people are very concerned about the gap between the rich and the poor in their country, majorities across the globe are willing to accept some inequality to have a free market system. A global median of 66% say most people are better off under capitalism, even if some people are rich and some are poor.

Belief in the free market tends to be highest in developing countries (median of 71%). Nearly two-thirds or more in all nine of the developing economies surveyed agree that most people benefit from capitalism, including 80% of Bangladeshis, 75% of Ghanaians and 74% of Kenyans.

Publics in emerging markets also generally support the free market. More than half in 21 of the 25 countries surveyed agree that most people are better off in a free market system even if there is some inequality, including roughly three-quarters or more in Vietnam, China, Nigeria, Turkey, Malaysia and the Philippines. Support is much lower in Colombia, Jordan, Mexico and Argentina. Argentines are the least likely to see the benefits of capitalism among all 44 countries surveyed.

Publics in emerging markets also generally support the free market. More than half in 21 of the 25 countries surveyed agree that most people are better off in a free market system even if there is some inequality, including roughly three-quarters or more in Vietnam, China, Nigeria, Turkey, Malaysia and the Philippines. Support is much lower in Colombia, Jordan, Mexico and Argentina. Argentines are the least likely to see the benefits of capitalism among all 44 countries surveyed.

Advanced economies are somewhat more divided over the free market. At least seven-in-ten in South Korea, Germany and the U.S. say most people are better off under capitalism, but fewer than half in Greece, Japan and Spain agree. In most advanced economies, people who say the gap between the rich and poor is a very big problem are much less supportive of the free market than those who worry less about inequality.

In general, there has been moderate change in support for the free market between 2007 and 2014 among the countries surveyed in both years. The Spanish (-22 percentage points) and Italians (-16) stand out for their declining belief in capitalism over the course of the global recession. At the other end of the spectrum, the Turks (+14) and Indonesians (+13) are more likely today to say the free market is better for everyone than they were seven years ago.

In some countries, lower income and less educated individuals are less likely to express support for capitalism than higher income and more highly educated people. The gap between lower and higher income people on this question is particularly large in Peru (-23 percentage points), Greece (-20) and France (-17). And the education differences are especially wide in Peru (-20), Pakistan (-18) and Nigeria (-16).

Global Opportunity Quiz

Global Opportunity Quiz