Most publics in the former Eastern bloc express support for the economic changes that have taken place in their countries since the collapse of communism, but views about the move from a statecontrolled economy to a market economy are much more negative than they were in 1991. As was the case nearly two decades ago, younger and better educated respondents are generally more enthusiastic about the economic changes their countries have undergone, as are men and those who live in urban areas.

Most publics in the former Eastern bloc express support for the economic changes that have taken place in their countries since the collapse of communism, but views about the move from a statecontrolled economy to a market economy are much more negative than they were in 1991. As was the case nearly two decades ago, younger and better educated respondents are generally more enthusiastic about the economic changes their countries have undergone, as are men and those who live in urban areas.

With the exception of Poland and the Czech Republic, majorities or pluralities in Eastern Europe say the economic situation of most people in their country is now worse than it was under communism. This view is particularly prevalent in Hungary, Bulgaria and Ukraine. (Those in the former East Germany were asked if their life is better off or worse off as a result of unification; see Chapter 5.)

When asked about their opinions of capitalism more generally, Eastern Europeans offer mixed views. Majorities in Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia say that people tend to be better off in a free market economy, even though some are rich and others are poor. In Hungary and Bulgaria, meanwhile, majorities disagree that free markets are better for most people. By comparison, people in the five Western European countries surveyed – including a majority of east Germans – endorse the free market approach.

The survey also finds that majorities or pluralities in all of the former Iron Curtain countries in the study say that it is true that the rich are getting richer while the poor are getting poorer, but this view is generally less widespread than it was in 1991. In east Germany, however, more see growing inequality today.

Declining Support for Move to Market Economy

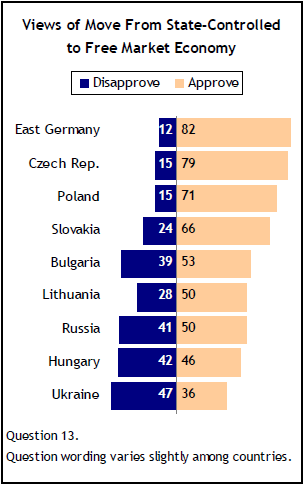

About eight-in-ten in east Germany (82%) and in the Czech Republic (79%) approve of their country’s move from a state-controlled economy to a free market economy. This view is also widely held in Poland (71%) and Slovakia (66%).

About eight-in-ten in east Germany (82%) and in the Czech Republic (79%) approve of their country’s move from a state-controlled economy to a free market economy. This view is also widely held in Poland (71%) and Slovakia (66%).

A slim majority of Bulgarians (53%) and half of Russians and Lithuanians support the economic changes that have taken place since the collapse of communism. Hungarians are nearly evenly split – 46% approve and 42% disapprove of the move to a market economy. And in Ukraine, just 36% are upbeat about the economic changes, while close to half (47%) express disapproval.

Publics in most of the former communist countries surveyed have much more negative opinions about the economic changes that have taken place in their country than they did in 1991. The drop in support for the move to a market economy has been especially steep in Hungary (34 percentage points), Lithuania (26 points), Bulgaria (20 points), and Ukraine (16 points). The drop has been modest, but still significant, in Poland (nine points) and the Czech Republic (eight points), where strong majorities continue to endorse the economic changes.

Demographic Gaps on Views of Economic Change

As was the case in 1991, women are generally less enthusiastic about the move from a state-controlled to a market economy. For example, 52% of Hungarian men approve and 38% disapprove of the economic changes that have taken place in their country since 1989. Hungarian women express more negative views – 41% approve and 45% disapprove of the changes. In Ukraine, just 30% of women approve of their country’s move to a market economy, while a majority (52%) disapproves; Ukrainian men are nearly evenly split (44% approve and 41% disapprove).

As was the case in 1991, women are generally less enthusiastic about the move from a state-controlled to a market economy. For example, 52% of Hungarian men approve and 38% disapprove of the economic changes that have taken place in their country since 1989. Hungarian women express more negative views – 41% approve and 45% disapprove of the changes. In Ukraine, just 30% of women approve of their country’s move to a market economy, while a majority (52%) disapproves; Ukrainian men are nearly evenly split (44% approve and 41% disapprove).

In Russia, however, the gender gap on views about economic changes since the collapse of communism has evaporated. In 1991, Russian men and women were more divided than men and women in any other country surveyed – 64% of men approved of the changes, compared with 46% of women. Today, about half of men (49%) and women (50%) express positive views of Russia’s move to a market economy.

In Russia, however, the gender gap on views about economic changes since the collapse of communism has evaporated. In 1991, Russian men and women were more divided than men and women in any other country surveyed – 64% of men approved of the changes, compared with 46% of women. Today, about half of men (49%) and women (50%) express positive views of Russia’s move to a market economy.

Views about the move away from a state-controlled economy also vary by age, with those under 30 expressing considerably more positive views about the economic changes that have taken place in their country than those who are 65 or older. The generation gap is widest in Russia, where a clear majority (63%) of respondents under 30 say they approve of the move to a market economy. Fewer than three-in-ten (27%) of those 65 or older share that view. Similarly, 66% among young Bulgarians have positive views of the economic changes in their country, compared with about one-third (32%) of those 65 or older.

In all of the Eastern European countries surveyed, those with at least some college education are more supportive – by double-digit margins – of the move from a state-controlled to a market economy than are those who did not attend college. In Hungary, about three-quarters (74%) of those who attended college approve of the changes, compared with 41% of those who did not. Among east Germans, however, support for the economic changes is about as high among those who did not attend college (82% approve) as it is among those who did (86%).

In some former communist countries, urban dwellers are more likely than those in rural areas to say they approve of the move to a market economy. This gap is especially evident in Hungary, where a slim majority of those in urban areas (52%) support the economic changes their country has undergone, compared with just one-third in rural areas. In 1991, majorities in both urban (83%) and rural (75%) parts of Hungary said they approved of the changes. By double-digit margins, urban residents also are more likely than rural residents to approve of the move away from a state-controlled economy in Bulgaria (16 percentage points), Russia (13 points), Lithuania (13 points) and Poland (10 points).

Many Say Economic Situation Is Worse Today

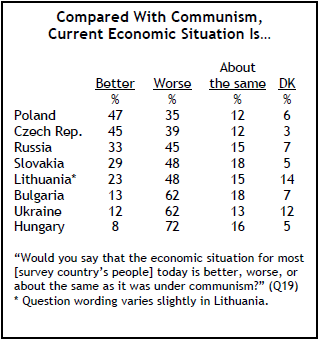

Majorities or pluralities in six of the eight Eastern European countries surveyed say the economic situation of most people in their country is worse today than it was under communism. Hungarians offer the most negative assessments – 72% say most in their country are worse off today. Majorities in Bulgaria and Ukraine share that view (62% each), as do about half of Lithuanians and Slovaks (48% each) and 45% of Russians.

Majorities or pluralities in six of the eight Eastern European countries surveyed say the economic situation of most people in their country is worse today than it was under communism. Hungarians offer the most negative assessments – 72% say most in their country are worse off today. Majorities in Bulgaria and Ukraine share that view (62% each), as do about half of Lithuanians and Slovaks (48% each) and 45% of Russians.

Only in Poland and the Czech Republic do more respondents say that most people in their country are better off than say most are worse off. Nearly half of Poles (47%) and 45% of Czechs say that the economic situation is better today than it was under communism, while 35% and 39%, respectively, say it is worse.

As is the case with opinions about the move from a state-controlled economy to a market economy, women, those who did not attend college and those who are 65 or older are generally more negative in their assessments of whether most people in their country are better off or worse off today than they were under communism. The views of those in urban or rural areas vary slightly, if at all.

In nearly every Eastern European country surveyed, those under 30 are much more likely than those 65 and older to say that the economic situation of most people in their country is better today than it was under communism. In Russia, 39% of those who were young children during the Soviet regime say people are better off today and one-third say people are worse off. Among those who are 65 and older, about six-in-ten (62%) say the economic situation of most Russians is worse today and just 20% say it is better than it was under communism. A similar pattern is evident throughout the region. In Ukraine, however, the young and old are about equally likely to say the economic situation is better (13% vs. 11%, respectively). At the same time, older Ukrainians are far more likely than young people to say the economic situation is now worse (75% vs. 50%).

Views of Free Markets

When asked whether they agree or disagree that most people are better off in a free market economy, even though some people may be rich while others are poor, Eastern European publics offer mixed views. Opinions are decidedly in favor of free markets in Poland (70%), the Czech Republic (63%) and Slovakia (56%). In Lithuania, half agree that people are better off in a free market economy, while 43% disagree. And in Ukraine, Bulgaria and Hungary, majorities or pluralities reject the notion that free markets are better, even if they produce inequalities (43%, 58% and 65%, respectively).

When asked whether they agree or disagree that most people are better off in a free market economy, even though some people may be rich while others are poor, Eastern European publics offer mixed views. Opinions are decidedly in favor of free markets in Poland (70%), the Czech Republic (63%) and Slovakia (56%). In Lithuania, half agree that people are better off in a free market economy, while 43% disagree. And in Ukraine, Bulgaria and Hungary, majorities or pluralities reject the notion that free markets are better, even if they produce inequalities (43%, 58% and 65%, respectively).

Views of free markets are, in large part, a reflection of opinions of how people have fared economically over the past two decades. For example, in Bulgaria, where overall support for free markets is low, more than seven-in-ten (73%) of those who say most people in their country are better off than they were under communism favor the free market model. Just 27% of those who say people are worse off today and 40% of those who say things are about the same for most people as they were under communism express support for free markets.

In comparison, majorities in all five Western European countries surveyed say that most people are better off in a free market economy. Support for free markets is highest among Italians (75%). And even in Spain, where fewer express positive views of free markets than in any other country in the region, about six-in-ten (59%) agree that most people are better off in a free market economy. Just one-third disagree.

Opinions about free markets are slightly more positive among those in the former West Germany than among those in the country’s east. About two-thirds of west Germans (66%) agree that most people are better off in a free market economy, even though some are rich and some are poor; 31% disagree. In east Germany, 59% agree that free markets are better for most people, while 39% disagree.

Throughout Eastern Europe, younger respondents are much more likely than older ones to agree that most people are better off in a free market economy. For example, nearly six-in-ten Ukrainians under 30 (58%) endorse a free market approach, compared with just one-third of those 65 or older. In Russia, 62% in the younger group say that free markets are better for most people, while 42% in the older group agree.

Age is also related to views of free markets in Germany, Spain, Britain and Italy, but, in those countries, young people register the lowest levels of support. The gap is especially wide in Germany, where 55% of those under 30 agree that people are better off in a free market economy, compared with 71% of those 65 or older. This primarily reflects differences among young and older respondents in west Germany; in the east, those under 30 are just six percentage points less likely than those 65 or older to express support for free markets (54% vs. 60%).

Despite the current economic crisis, support for free markets in most of the former communist countries surveyed has changed little since 2007, when Eastern European countries were on better economic footing. For example, 63% in the Czech Republic now say they agree that most people are better off in a free market economy. That is virtually unchanged from 60% two years ago. More than half (52%) of Russians support free markets, about equal to the percentage that shared that view in 2007 (53%). In Ukraine, however, views of free markets are decidedly more negative today – 46% say most people are better off in a free market economy, compared with 66% two years ago.

Eastern Europeans See Less Inequality

Majorities or pluralities in the eight Eastern European countries surveyed say that “the rich just get richer while the poor get poorer.” Hungarians are the most likely to say that is the case – 77% agree – followed by Bulgarians (58%), Lithuanians (57%) and Poles (55%). About half in the Czech Republic (50%), Slovakia (49%), Ukraine and Russia (48% each) also say that the rich are getting richer while the poor are getting poorer.

Majorities or pluralities in the eight Eastern European countries surveyed say that “the rich just get richer while the poor get poorer.” Hungarians are the most likely to say that is the case – 77% agree – followed by Bulgarians (58%), Lithuanians (57%) and Poles (55%). About half in the Czech Republic (50%), Slovakia (49%), Ukraine and Russia (48% each) also say that the rich are getting richer while the poor are getting poorer.

Compared with 1991, publics in Russia, Ukraine, Slovakia, Poland and Bulgaria today are much less likely to say that there is growing inequality. The decline has been steepest in the former Soviet republics of Russia and Ukraine. Soon after the collapse of the Soviet Union, nearly seven-in-ten Russians (69%) and just slightly fewer Ukrainians (65%) said the rich were getting richer while the poor were getting poorer.

In Western Europe, publics in Germany – both east and west – and France are more likely than they were in 1991 to perceive inequality. In west Germany, 55% now say the rich are getting richer while the poor are getting poorer, compared with just 37% in 1991; in east Germany, 63% say that is the case today, while 53% shared that view nearly two decades ago. By contrast, the percentage in Spain who agree that the rich are getting richer while the poor are getting poorer has dropped from 51% in 1991 to 41%. There has been virtually no change in Britain (36% then vs. 35% now) or Italy (49% vs. 47%).