Black Americans have been hit hard by the coronavirus outbreak, accounting for a disproportionate share of COVID-19 deaths. At the same time, they stand out from other racial and ethnic groups in their attitudes toward key health care questions associated with the outbreak. In particular, black adults are more hesitant to trust medical scientists, embrace the use of experimental medical treatments and sign up for a potential vaccine to combat the illness, according to a recent Pew Research Center survey.

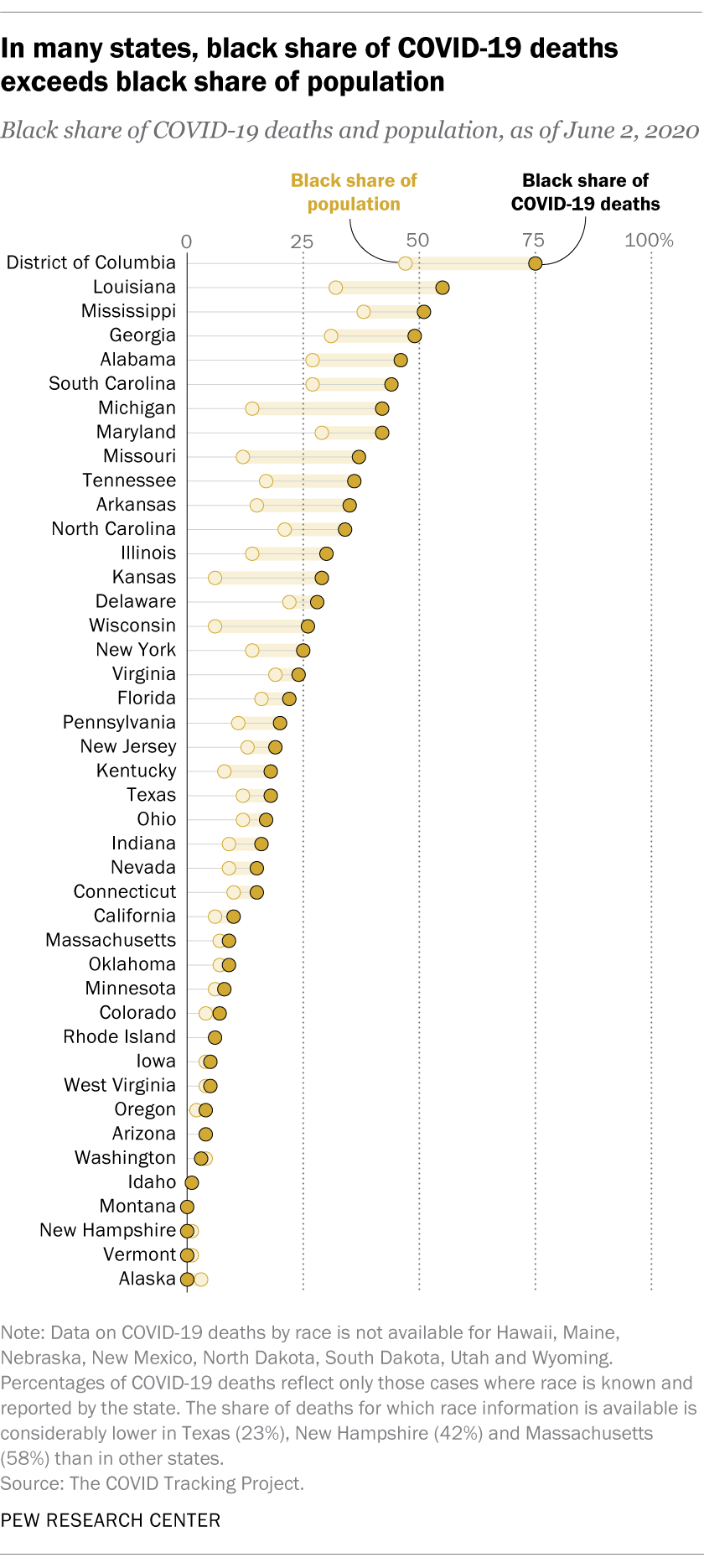

Nationally, black Americans account for about 13% of the U.S. population but 24% of the coronavirus deaths for which racial or ethnic information was available as of June 2, according to The COVID Tracking Project.

Nationally, black Americans account for about 13% of the U.S. population but 24% of the coronavirus deaths for which racial or ethnic information was available as of June 2, according to The COVID Tracking Project.

The disparity is particularly wide in some states. In Kansas and Wisconsin, black people account for 6% of each state’s population but 29% and 26% of deaths, respectively – the biggest proportional disparities out of the states for which demographic data on coronavirus deaths is available. In Missouri, blacks account for 12% of the population but 37% of deaths. In eight states overall, the black share of coronavirus deaths is at least twice as high as the black share of the population.

Public health experts have offered a mix of explanations for these disparities. They include higher rates of preexisting health conditions that increase the risk of complications from the coronavirus; social and economic factors that contribute to health risk; and long-standing inequities in health care access and outcomes for black Americans compared with other racial and ethnic groups.

The experiences and attitudes of black Americans during the coronavirus pandemic have drawn national attention. This analysis is based on data from multiple sources.

Data about COVID-19 deaths among black Americans is drawn from The COVID Tracking Project. All data is current as of June 2, 2020. Not all states report the race of those who have died from the virus, and even in some states that do report it, racial information is available for a relatively small share of total COVID-19 deaths. In Texas, for example, racial information is available for only around a quarter of total COVID-19 deaths (23%).

The attitudinal data in this analysis is based on a survey of 10,957 U.S. adults conducted April 29 to May 5, 2020, as well as an earlier survey of 10,139 adults conducted April 20 to 26, 2020. Everyone who took part in both surveys is a member of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology.

In the Center’s recent survey – conducted April 29 to May 5 among 10,957 U.S. adults – around seven-in-ten black adults (71%) said public health officials like those at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are doing an excellent or good job responding to the coronavirus outbreak. The views of black Americans on this question are about the same as those of Hispanic and white adults.

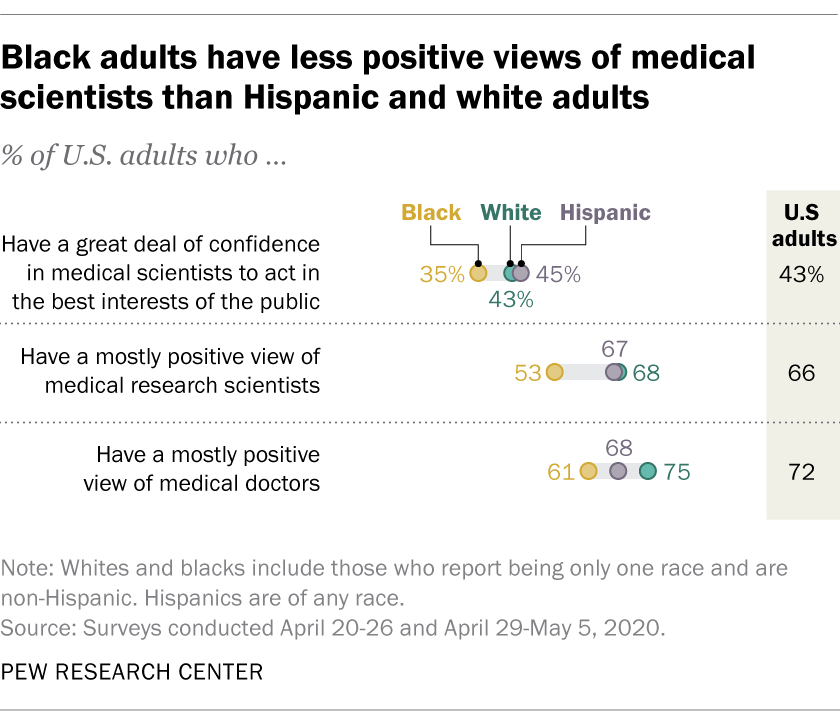

But when it comes to broader expectations and trust in medical researchers, black adults are more wary. For example, 35% of black Americans have a great deal of confidence in medical scientists to act in the public interest, compared with 43% of white adults.

But when it comes to broader expectations and trust in medical researchers, black adults are more wary. For example, 35% of black Americans have a great deal of confidence in medical scientists to act in the public interest, compared with 43% of white adults.

Similar patterns appear on other questions, too. Around half of black Americans (53%) have a mostly positive view of medical research scientists, compared with around two-thirds of Hispanic (67%) and white adults (68%). And around six-in-ten black adults (61%) have a mostly positive view of medical doctors, versus 75% of white adults. (On some questions in this analysis, the differences in views between black and Hispanic adults are not statistically significant.)

The less trusting and less positive overall views that black adults express toward medical experts are in line with those documented in past Center surveys. In a January 2019 survey, for instance, black Americans expressed more mixed views about the effects that science has had on society, and they were more likely than whites to say misconduct among medical experts is a big problem.

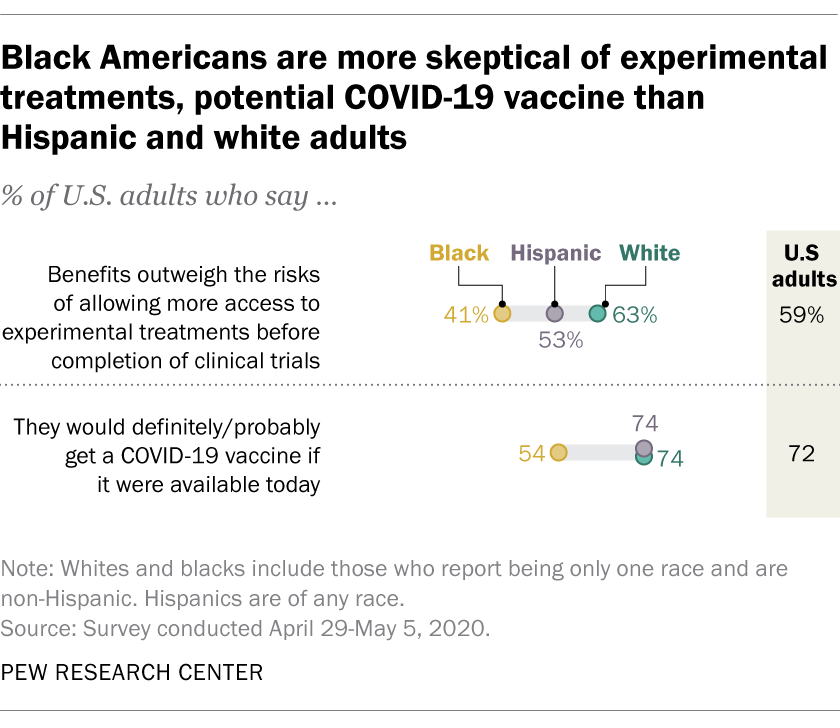

In the more recent survey, black adults also express more wariness than Hispanic and white adults about some forms of medical care, including expanding access to experimental drugs before clinical trials are completed, as is occurring now with some coronavirus patients. A 57% majority of black adults say the risks of expanding experimental treatments outweigh the benefits, while 41% say the benefits outweigh the risks. Hispanic (53%) and white adults (63%) are more likely than black adults to say the benefits outweigh the risks.

In the more recent survey, black adults also express more wariness than Hispanic and white adults about some forms of medical care, including expanding access to experimental drugs before clinical trials are completed, as is occurring now with some coronavirus patients. A 57% majority of black adults say the risks of expanding experimental treatments outweigh the benefits, while 41% say the benefits outweigh the risks. Hispanic (53%) and white adults (63%) are more likely than black adults to say the benefits outweigh the risks.

Meanwhile, a little over half of black adults (54%) say they would definitely or probably get a coronavirus vaccine if one were available today, while 44% say they would not. Hispanic and white adults are far more likely to say they would get the vaccine: 74% in both groups say they would, while around a quarter say they would not.

Previous Center research also has found more ambivalence toward vaccines among black Americans.

In a 2016 Pew Research Center survey, over half of black adults (56%) said they saw high preventive benefits from the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine for children. That compared with 79% of white adults. Conversely, 44% of black adults said there were medium or high risks of side effects from the childhood MMR vaccine, compared with 33% of Hispanic and 30% of white respondents.

Data from the federal government has also shown that black Americans sometimes have lower vaccination rates than those in other racial and ethnic groups.

Note: Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology.